'The Great Migration' is a story of motion under constraint, a story that can be mapped onto later movements of displaced people, job seekers, refugees, and migrants of all kinds.

'The Great Migration' is a story of motion under constraint, a story that can be mapped onto later movements of displaced people, job seekers, refugees, and migrants of all kinds.

By KOLUMN Magazine

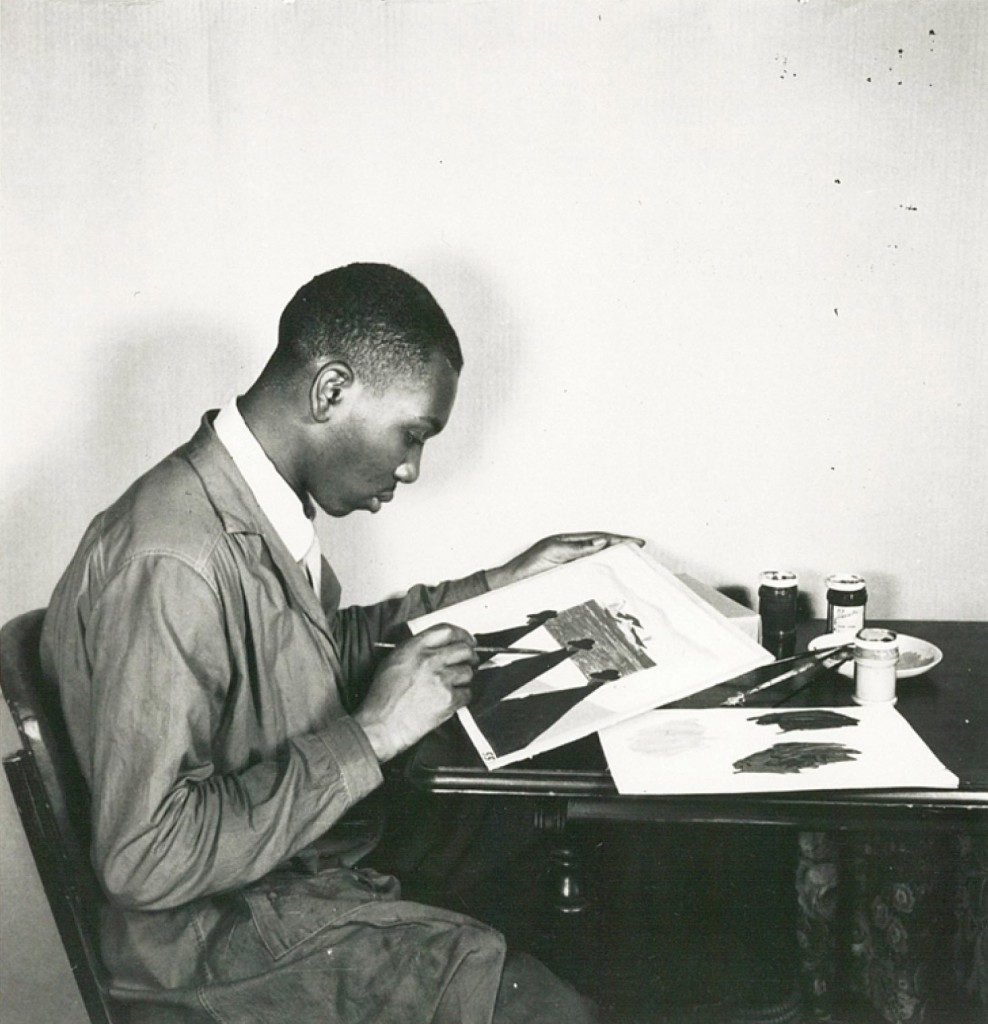

In the middle of the twentieth century—when American art was busy deciding whether the future belonged to abstraction, irony, or spectacle—Jacob Lawrence made a different wager. He believed history could be told plainly, without being simplified; that modernism could be sharp-edged and experimental without turning away from human beings; and that Black life in America was not a niche subject but the nation’s core material. He built his signature language from compact panels, flattened perspective, and colors that behave like moral forces. He added captions that refuse the haze of interpretation; they insist on facts, or at least on claims sturdy enough to be argued with. You can stand in front of a Lawrence and feel the double effect: the image moves quickly, almost like a poster or a frame of film, but the longer you stay the more it reads like an archive—carefully researched, insistently composed, and unwilling to let the viewer drift into aesthetic distance.

That dual commitment—to beauty and to testimony—helps explain why Lawrence has become one of the most reproduced, studied, and institutionally embraced American painters of his generation, even as his work continues to unsettle easy narratives about whose experiences count as “American.” The art market has long had its uses for him, and museums have their own reasons to claim him, but Lawrence is ultimately difficult to domesticate. His pictures are too direct for nostalgia, too unsentimental for uplift, too modern for folklore, too grounded for myth. They declare that migration is not an abstraction; it is a crowded station, an exhausted body, a rent bill, a job line, a courtroom, a tuberculosis ward, a riot. They declare that the American Revolution is not only powdered wigs and marble rhetoric; it is also the brutal arithmetic of power, labor, land, and exclusion, told through quotations and scenes that feel like warnings delivered across time.

Lawrence’s most famous achievement, The Migration Series (1940–41), is often introduced as a masterpiece of narrative painting: sixty small tempera panels that trace the mass movement of Black Southerners to Northern and Midwestern cities, one of the most consequential demographic shifts in modern U.S. history. The temptation is to treat the series as a single iconic work, a monument you salute and move on from. But Lawrence’s career can’t be contained by its best-known object any more than the Great Migration can be reduced to a single cause. The series is a hinge: it opens into the earlier Lawrence, a young Harlem artist studying at the library, learning how to compress history into images without turning people into symbols; and it opens into the later Lawrence, who carried his narrative urgency into war, labor, urban life, teaching, and public art, while defending figuration against the fashionable currents that might have made him richer or trendier but less himself.

To write about Jacob Lawrence is to write about a painter who approached the United States the way a journalist might—except his deadlines were measured in decades, and his reporting was rendered in color and shape rather than in sentences. (A later critic would name this quality outright, describing Lawrence’s work as a kind of “first draft of history.”) It is also to write about a man whose art was inseparable from community: from Harlem’s workshops and mentors, from the artists and writers around him, from his marriage to Gwendolyn Knight—an artist in her own right and his most valued critic—and from the classrooms where he insisted that the making of art was a civic act, not merely a personal one.

Harlem, the library, and the making of a narrator

Jacob Armstead Lawrence was born in 1917 in Atlantic City, New Jersey, and came of age amid the geographic instability that marked many working-class Black families in the early twentieth century. His childhood moved through New Jersey and Philadelphia before Harlem became the place that formed him most profoundly. Harlem in the 1930s was not a museum-piece idea of a renaissance; it was a living neighborhood marked by overcrowding, struggle, political argument, storefront churches, street-corner oratory, jazz, rent, and the daily improvisations of survival. It was also a place where institutions—some formal, some improvised—treated Black creativity as something worth cultivating rather than merely consuming.

Lawrence found his way into that ecosystem through community art programs and workshops, spaces where a young person could learn technique while also absorbing a sense of why art mattered. The Archives of American Art’s records on Lawrence and Knight, along with the Smithsonian’s oral history materials, locate him within that broader world of Harlem training and mentorship, the kind of formation that doesn’t always read as glamorous but often proves decisive: the patient work of being taught, corrected, and challenged. Harlem’s art scene gave Lawrence models of possibility—artists who treated Black subjects as worthy of serious modern treatment—and it also gave him a discipline that would remain visible in his mature work: the instinct to organize a picture around structural clarity, to let rhythm and repetition carry narrative, and to treat color not as decoration but as an engine of meaning.

Just as crucial was the library. Multiple accounts of Lawrence’s practice emphasize his research habits, particularly his relationship to Harlem’s 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library—later known as the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture—where he studied Black history and encountered archives that contradicted the omissions of mainstream education. The library wasn’t only a repository; it was a counter-curriculum. There, Lawrence could read about figures like Toussaint L’Ouverture, Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Tubman as historical agents rather than footnotes, and he could see how narrative itself—who is allowed to be a protagonist, whose suffering is described, whose victories are recorded—becomes a battleground.

That realization shaped Lawrence’s early breakthrough: his sequence paintings on Black historical figures. Before he ever painted the Great Migration, he practiced the art of serial narration by producing multipanel cycles devoted to Toussaint L’Ouverture (1938), Frederick Douglass (1939), and Harriet Tubman (1940). These works are sometimes treated as apprenticeship, but they are more accurately understood as method. Lawrence was inventing a form: history painting scaled down, modernized, and re-anchored in Black experience. He was also training himself to think like a storyteller who cannot afford drift. Each panel needed to stand alone visually while also serving the larger arc. Each image needed to clarify rather than merely suggest. It is difficult to look at these early series and not see the template for what would come next: a painter who found his subject in collective struggle and who believed that sequence—image after image, claim after claim—could build an argument strong enough to resist erasure.

The WPA years and the politics of making a living

Lawrence’s emergence occurred during the Depression, when the United States briefly, unevenly, and controversially treated artists as workers—people who could be employed, paid, and expected to produce as part of a public project. Lawrence secured work through the WPA Federal Art Project in 1938, a fact documented in biographical notes associated with the Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight papers. The WPA matters here not simply as a line on a résumé, but as a context that sharpened Lawrence’s sense of labor, class, and the material conditions of creativity. When art is framed as work—work done in community, under constraints, in exchange for survival—the question of what you choose to paint changes. The painter becomes accountable not only to patrons and critics but also to neighbors, peers, and the public whose taxes, politics, or pressure make such programs possible.

It is also during this period that Lawrence’s partnership with Gwendolyn Knight became central. Knight, herself a serious artist, met Lawrence in Harlem’s workshop world, and the Archives of American Art notes that they met in Augusta Savage’s workshop and married in 1941. Their relationship is often described through a familiar shorthand—muse, supporter, critic—but that language flattens what seems to have been, by many accounts, an unusually rigorous artistic partnership. The Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation describes Knight as Lawrence’s most valued critic, and emphasizes that she maintained her own creative path even while being deeply intertwined with his life. In a culture that loves the solitary-genius myth, their long marriage stands as a different model: the sustained dialogue, the shared discipline, the private feedback loop without which the public work might have been less exact.

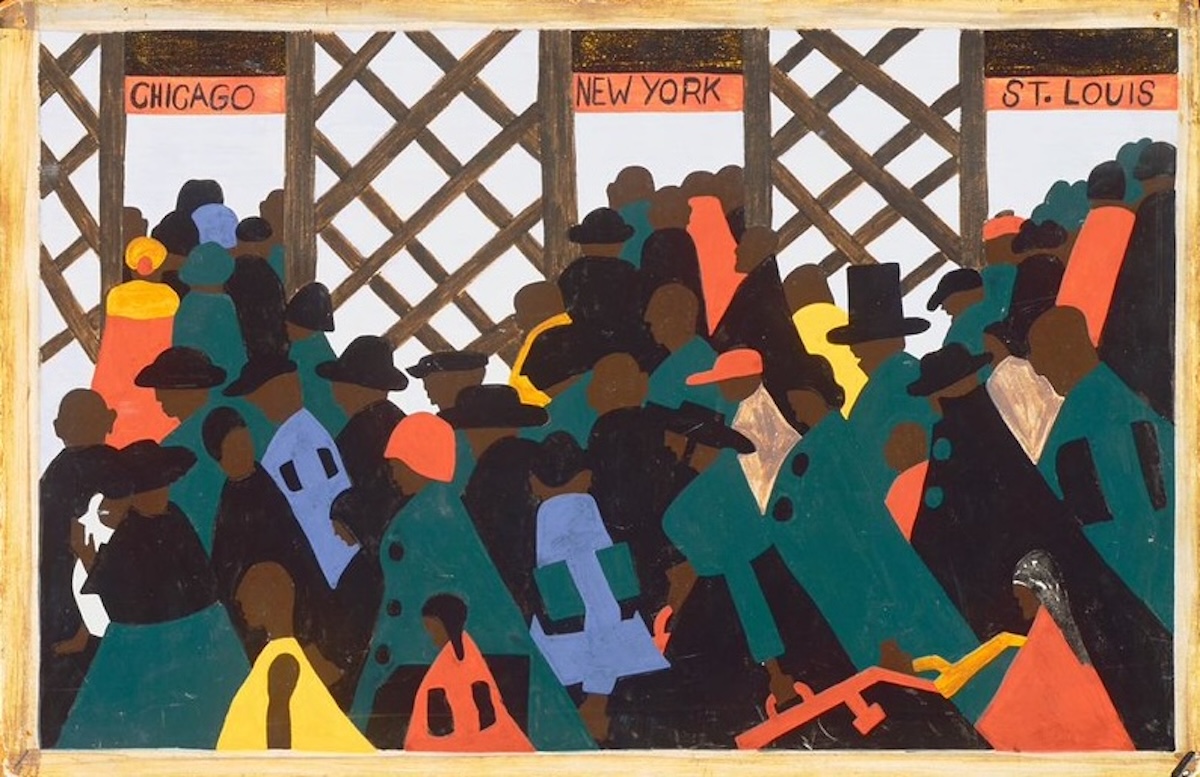

The Migration Series: Compressing a people’s movement into sixty arguments

Lawrence began The Migration Series in 1940, when he was still in his early twenties, and completed it in 1941. The Phillips Collection’s extensive digital project on the series presents it as an “ambitious 60-panel series portraying the Great Migration,” emphasizing Lawrence’s own understanding of the project as something unprecedented in American visual art at the time: a broad, complex historical subject tackled through serial modern painting. The Museum of Modern Art, in its exhibition materials, underlines the physical reality of the series: sixty tempera paintings on 18-by-12-inch boards, each accompanied by a caption that Lawrence revised for later presentations, and contextual materials that recall the first New York showing at Edith Halpert’s Downtown Gallery in 1941.

Those details matter because they point to what Lawrence was really doing. Scale, for one: at 12 by 18 inches each, the panels insist on intimacy. You cannot experience them like murals from a distance. You must step close, track the rhythm, and submit to sequence. That intimacy is not merely aesthetic; it mirrors the series’ ethical stance. The Great Migration can be narrated as statistics, as labor history, as political transformation. Lawrence does not deny any of that, but he insists on the human-scale scene: the family leaving, the worker arriving, the crowd pressed together, the invisible weight of Jim Crow pushing bodies northward.

The series is structured by causes and consequences rather than by individual hero worship. While Lawrence had painted towering figures like Tubman and Douglass, here he shifted the center of gravity toward collective movement—what it looks like when a people act not as a handful of famous leaders but as millions of ordinary decision-makers. That point is made explicitly in contemporary commentary on the series’ research origins and narrative focus: Lawrence studied history at Harlem’s library, drew from that archive, and used it to build a story of collective motion rather than a gallery of singular icons.

Lawrence’s captions, which can read like clipped reportage, are crucial to this collective emphasis. They provide context but also discipline interpretation. The viewer is not free to float in symbolic vagueness; the caption anchors the scene in a specific claim about wages, segregation, violence, labor demand, housing, disease, or aspiration. In some panels, the image shows what the caption names; in others, the caption pushes against what the image alone might suggest, creating tension that feels almost editorial. The effect is that of a storyboard fused with a sociological pamphlet, except rendered with the formal intelligence of modern painting.

Formally, Lawrence’s approach in Migration is both austere and electrifying. Figures are frequently simplified into silhouettes or flattened bodies that read as both individuals and types. Perspective bends; interiors tilt; the geometry of stairs, platforms, factory floors, and tenement rooms becomes a kind of architecture of pressure. Color operates as a system: repeated hues stitch panels together; sharp contrasts carve emotion into space. Museums and scholars often describe this as a modernist language that remains narrative rather than abstract—an important distinction in an era when narrative painting was frequently dismissed as old-fashioned. Lawrence’s achievement was to make narrative feel modern not by abandoning story, but by modernizing its grammar.

In the best moments, Lawrence turns structural repetition into a moral argument. A train platform appears again and again; crowds accumulate; lines form; bodies wait. The recurrence suggests what the Migration demanded: endurance, patience, and the willingness to live inside transitions. The North is not painted as paradise. It is painted as crowded, tense, and still stratified—yet threaded with possibility. That refusal of easy uplift is one reason the series remains contemporary. It is a story of motion under constraint, a story that can be mapped onto later movements of displaced people, job seekers, refugees, and migrants of all kinds.

Institutions have increasingly treated The Migration Series as a central work of American art, not simply African American art. The MoMA exhibition framing emphasizes the series’ original 1941 presentation and the material specifics of its making and display, reinforcing how quickly it entered the mainstream art conversation even amid a segregated culture. And yet, the series’ subject—Black flight from Southern terror and economic exploitation—reminds us that “mainstream” recognition has always been partial, negotiated, and contested. Lawrence, painting in 1940–41, was documenting a mass movement shaped by white supremacist law and practice; he was also painting the consequences that Northern cities would rather treat as incidental than as the result of American design.

A later generation of critics would frame the series’ journalistic intensity with particular force. Writing in The Nation, Syreeta McFadden described Lawrence’s approach as art that behaves like journalism, capturing the Great Migration as a defining moment and offering a visual “first draft” of that history. The phrase lands because it clarifies what Lawrence’s captions and sequence actually do: they don’t merely illustrate; they report, assert, and insist.

War, service, and the discipline of displacement

Lawrence’s sense of displacement—so central to Migration—deepened during World War II. He served in the U.S. Coast Guard, and his wartime experience informed the War Series, a sequence of fourteen panels that track the arc from “Shipping Out” to “Victory.” The Whitney Museum’s collection materials emphasize that the series was rooted in first-hand experience of regimentation, community, and displacement, including Lawrence’s early service in a racially segregated regiment where he held the rank of Steward’s Mate, one of the limited roles available to Black Americans at the time.

The Coast Guard context matters because it connects Lawrence’s art to a distinct kind of American contradiction: fighting for democracy abroad while living under segregation at home. In the War Series, Lawrence does not present war as pure heroism or pure horror; he presents it as a system that organizes bodies, compresses individuality, and turns movement into orders. If Migration paints movement as a choice shaped by structural violence, the war paintings show movement as command: the ship, the barracks, the uniform, the body reduced to function. Yet even here, Lawrence’s eye is not only critical; it is attentive. He notices camaraderie, collective labor, the strange intimacies of shared constraint.

Stylistically, the wartime panels extend Lawrence’s modernist discipline. Silhouettes sharpen. Spaces become more schematic. The narrative continues to unfold through repetition and variation: bodies in formation, bodies in transit, bodies waiting. This is where Lawrence’s “dynamic” composition—his way of making diagonals, stair-steps, and tilted planes carry emotional force—feels particularly suited to the subject. War is, among other things, a machine for organizing space, and Lawrence paints that organization as both pattern and pressure.

After Migration: Labor, city life, and the refusal to become a symbol

One risk of early acclaim is becoming trapped by your own signature. Lawrence’s response was to keep painting the world around him with the same narrative urgency he had brought to history. He made paintings of workers and builders, of street life, of interiors charged with quiet tension. These works are sometimes treated as “genre” scenes in contrast to the “epic” Migration, but that division misses Lawrence’s deeper continuity. For him, labor and daily life were not separate from history; they were history’s texture. If the Great Migration was a movement toward industrial jobs and urban possibility, then the depiction of workers, construction, and city rhythms is not a change of subject but a continuation of the same story at a different scale.

Lawrence’s commitment to figuration also became, in its own way, an ethical stance. As mid-century American art institutions increasingly celebrated abstraction—especially Abstract Expressionism—Lawrence remained committed to the legibility of the human figure and to the narrative frame. This was not a rejection of modernism; his work was modern to the core. It was a refusal to accept that modernity required abandoning people as subjects. That refusal, over time, has made him newly relevant, as contemporary audiences hunger for art that can hold formal intelligence and social meaning in the same frame without collapsing into propaganda or pure aesthetics.

Struggle: Rewriting the national origin story

If The Migration Series is Lawrence’s epic of Black movement within the United States, Struggle: From the History of the American People (1954–56) is his epic of the United States itself—an attempt to paint the nation’s founding not as settled legend but as contested process. The series comprises thirty panels and, for decades, was rarely seen reunited. The Metropolitan Museum of Art described its 2020 exhibition, Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle, as featuring the “little-seen” series and emphasized the significance of reuniting the multipaneled work for the first time in more than half a century.

Lawrence’s approach in Struggle is characteristic: he builds narrative through sequence, anchors meaning through text—here, quotations that range across voices and moments—and uses modernist compression to strip away the grandeur that often coats Revolutionary-era storytelling. The series’ very title insists that the United States is not a finished product but an ongoing contest. That contest includes liberty and aspiration, but also land theft, exclusion, class tension, and the violent enforcement of hierarchy. In other words, Lawrence paints the founding as an argument about who counts as “the people”—an argument that never really ends.

The Peabody Essex Museum, in presenting the series, framed it as Lawrence’s revolutionary narrative and underscored the historical quotations embedded in the panels, reinforcing how Lawrence positioned the work as both art and documentary claim. The quotations do not merely decorate; they function like evidence. They also reveal Lawrence’s sense of how power speaks. In choosing and placing these words, he performs an editorial act, reminding viewers that history is written not only by victors but by those who control archives, print, and memory.

One of the most striking episodes in the modern afterlife of Struggle involves absence and recovery: a panel long missing from public view was located after decades, a discovery reported in 2021 and tied to renewed attention to Lawrence’s historical project. The rediscovery story is more than art-world trivia. It mirrors Lawrence’s central theme: that national narratives are full of gaps, that what is lost is often politically meaningful, and that recovery is itself a kind of struggle.

The public artist: “New York in Transit” and art for the everyday crowd

Lawrence’s public work New York in Transit—a glass mosaic installed in the Times Square–42nd Street subway station—extends his commitment to ordinary people into the literal infrastructure of the city. The MTA’s Arts & Design collection describes the work as a glass mosaic showing figures and city life viewed from an elevated train, installed at one of the most heavily trafficked stations in New York. It is difficult to imagine a more fitting site for Lawrence: a place defined by movement, crowding, labor, and the daily choreography of bodies in transit. In a sense, the subway is a modern echo of the platforms and trains of Migration, stripped of its single historical moment but still animated by the same dynamics of flow, aspiration, and pressure.

That this work is often described as his final public art project only heightens its symbolic resonance. Lawrence, the painter of movement, left a permanent image inside a machine of movement—art embedded in the commute, available to people who are not museum-goers, encountered at speed, repeated day after day until it becomes part of a city’s visual memory.

Seattle, teaching, and the quiet power of influence

Late-career Lawrence is sometimes narrated as a relocation story: Harlem to Seattle, East Coast art circuits to the Pacific Northwest. The move, in 1971, brought Lawrence and Knight to Seattle, where he taught at the University of Washington. A regional historical account emphasizes their arrival in Seattle with his teaching appointment and underscores their shared reputation as artists, printmakers, educators, and activists, as well as the long arc of their lives there.

Teaching mattered to Lawrence not as retirement activity but as continuation. His work had always been shaped by institutions that taught, mentored, and funded artists—community centers, workshops, the WPA. Becoming a professor allowed him to return that investment and to shape future generations’ understanding of what art could do. Influence, in this model, is less about style imitation than about permission: the permission to treat Black life as central, to treat history as contested, to treat narrative as modern, to treat research as an artistic tool.

Lawrence remained active late into his life. The foundation’s biography notes that he was painting until weeks before his death in June 2000, completing new works in late 1999 and leaving another group unfinished. The Washington Post obituary reported his death in Seattle on June 9, 2000, noting him as a painter whose bold colors illuminated Black experience, especially through Migration. The convergence of those accounts—the man still working, the public recognizing him as a major chronicler—underscores a final Lawrence theme: the refusal to treat art-making as separate from living.

Institutions, ownership, and the politics of canonization

Lawrence’s career also illustrates the complicated relationship between Black achievement and institutional canon. Museums now present him as foundational, and his work is collected, toured, and taught as central to American modernism. MoMA’s materials emphasize his early breakthrough and the importance of The Migration Series as a major exhibition object. The Phillips Collection has built an expansive interpretive project around the series, framing it as a lens for understanding the lasting cultural and political impact of the Great Migration, and inviting public engagement that extends beyond traditional wall labels.

But canonization is not a neutral process. It involves choices about what gets shown, conserved, acquired, and narrated. Lawrence understood this, which is partly why he embedded text into his work: he did not want the picture to be separated from the claim. And his captions continue to complicate the institutional appetite for beauty. A museum can display Migration as color and design, as a triumph of modern composition, but the captions keep pulling the viewer back toward Jim Crow, labor exploitation, and Northern overcrowding. The work is, in this sense, resistant to aesthetic laundering.

Popular Black media outlets have also played a role in interpreting Lawrence for broader audiences. Ebony’s coverage of Migration in connection with a major museum presentation highlights how the series resonates beyond academic art history, and how curators and writers continue to debate what Lawrence was doing—how he drew on writers and other artists, how he built an ecosystem around the work rather than treating it as isolated genius. (Ebony) The Root, similarly, has framed the series as a researched narrative rooted in Harlem’s library culture and presented it as an essential experience for contemporary audiences encountering it in New York. (The Root) These interpretations matter because they refuse the narrowing that sometimes happens when Black artists enter the museum canon: the flattening into “first,” “representative,” or “important” without the harder question of what the work demands of the country.

Lawrence’s method: Clarity, sequence, and the moral geometry of color

What, finally, is Lawrence’s artistry—beyond biography and beyond the headline works? It is tempting to describe his style in shorthand: flat planes, bold colors, angular figures, narrative panels. But that list does not capture the intelligence of his method. Lawrence’s pictures are composed like arguments. He reduces detail not because he lacks skill but because he is pursuing force. The simplification is strategic; it increases legibility and speeds comprehension, allowing the viewer to register the story even before fully absorbing the composition.

Sequence is equally strategic. Lawrence understood that a single image can be absorbed too quickly, aestheticized, or misunderstood. Sequence slows the viewer down by repetition: it compels comparison. One panel leads to another, and the viewer begins to notice patterns—crowding, lines, separation, signs, windows, doors, staircases, uniforms, tools. Those repeated elements become the series’ real subject: systems. Lawrence paints systems through their effects on bodies.

Color, in Lawrence, operates as structure. Rather than using color to mimic natural appearance, he uses it to organize space and emotion. Repeated color chords tie panels together; sudden contrasts create impact. In Migration, color often behaves like a social map: clusters, separations, crowd densities. In War, it becomes regimental—uniformity interrupted by flashes. In Struggle, it turns historical scenes into present-tense warnings.

Text, finally, is Lawrence’s quiet radicalism. Visual art institutions have often treated text as secondary—an add-on, a label, a guide. Lawrence made it integral. In Migration, the captions are not optional; they are part of the work’s architecture. MoMA’s materials emphasize that Lawrence revised these captions, suggesting he understood them as living components of the narrative, subject to the shifting language of time and audience. In Struggle, the quotations function as evidence and argument, inserting the voices of the past into the visual present. This blending of image and text makes Lawrence unusually suited to the contemporary media environment, where stories circulate as sequences—slideshows, feeds, storyboards—and where the struggle over interpretation is constant.

What the work asks of us now

The most durable art does not merely survive its era; it re-enters new eras as if it has been waiting there all along. Lawrence’s work has done this repeatedly. In moments of renewed debate over migration, citizenship, labor, and racial violence, The Migration Series reads not as a completed chapter but as an origin point for patterns that persist. In moments when the nation argues over whose history is taught, Struggle returns as a reminder that the founding itself was always contested and that “the people” has always been a fought-over phrase. In a time when visual culture moves fast, Lawrence’s panels feel built for speed—but they also punish speed, because the sequence insists on attention.

Lawrence also remains a guide for institutions still learning how to tell fuller stories. Museums now routinely declare commitments to diversity, equity, and inclusion. Lawrence’s work offers a harder test: can an institution present beauty without neutralizing the politics that beauty carries? Can it treat Black history not as a special exhibition theme but as a permanent part of national narrative? Can it sustain the research, context, and public engagement that a series like Migration requires? The Phillips Collection’s expansive interpretive platform for the series, for example, suggests one answer: treat the work not as static treasure but as an invitation into layered history, personal testimony, and ongoing dialogue.

To understand Lawrence is also to understand something about the American twentieth century: the movement of Black families northward and outward, the war fought in the name of freedom amid segregation, the postwar battles over memory, the long argument over democracy’s meaning. Lawrence painted these not as distant subjects but as lived conditions. He did it with a style that refused sentimental fog and with a discipline that kept his work legible to ordinary viewers without surrendering complexity.

In the end, Lawrence’s greatest accomplishment may be that he made American history feel like something you could see happening—not only in the past tense, but now. His panels do not ask for passive admiration. They ask for witness. They ask the viewer to accept that history is not an abstraction, not a chapter heading, not a patriotic mural at a comfortable distance. History, Lawrence insists, is bodies in motion under pressure, people making decisions inside constraints, and a nation whose promises are always being tested by the lives it tries to exclude.

That insistence is why Jacob Lawrence’s work endures: not as a relic of a particular movement or moment, but as a permanent challenge—clear, strong, and universal in the hardest sense of the word.

The Long Arc of Anna Julia Cooper