Intersectionality is widely known; the lives it was meant to make visible are still too often rendered invisible by institutions that prefer simpler stories.

Intersectionality is widely known; the lives it was meant to make visible are still too often rendered invisible by institutions that prefer simpler stories.

By KOLUMN Magazine

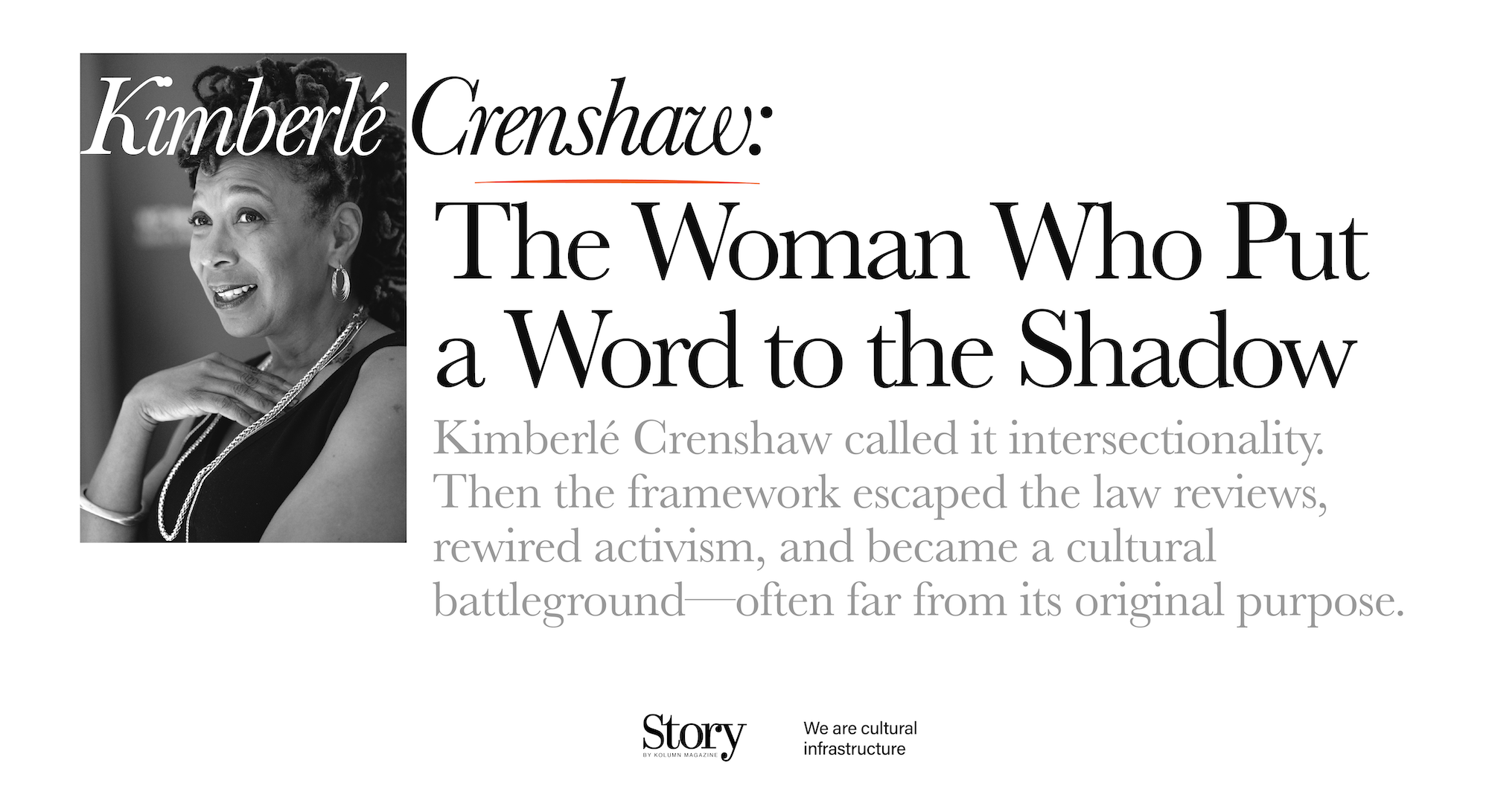

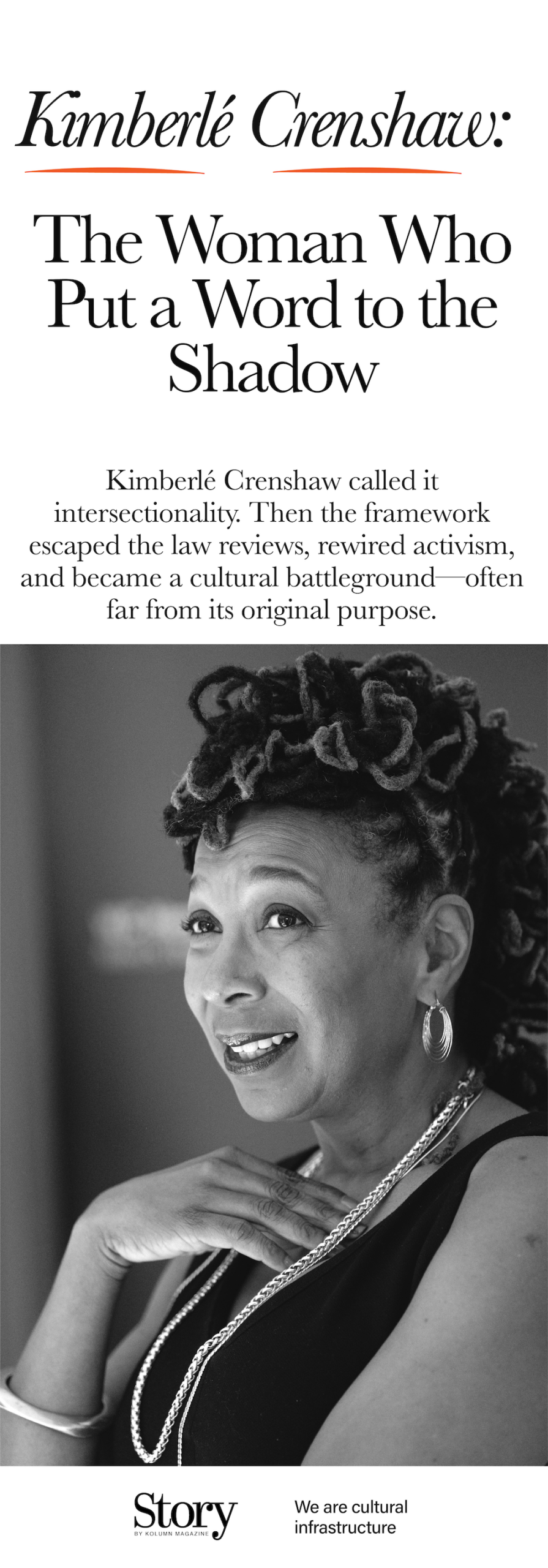

It’s difficult to remember, now that “intersectionality” appears on syllabi, HR trainings, nonprofit mission statements, and political talk shows, that the concept was coined as a corrective—an intervention in legal common sense. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s core claim was not that identity is infinitely divisible, or that politics should become a contest of personal biography. It was something more concrete, and, in its original form, more prosecutorial: the law, as practiced and interpreted, repeatedly failed to recognize how discrimination compounds. People whose injuries are produced by more than one axis—race and gender, for example—often cannot get the system to “see” what happened to them, because doctrine prefers single-cause explanations and neat categories.

The best origin stories in American intellectual life are also courtroom stories: a small, specific set of facts revealing a bigger flaw in the architecture. Crenshaw’s early writing repeatedly returns to this kind of evidentiary moment—an employment policy, a shelter intake rule, an antidiscrimination test—that looks neutral when viewed through one lens and starkly discriminatory when viewed through more than one. In her now-canonical essay “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex,” she argued that antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics had each developed patterns of selective attention. They tended to defend the most “representative” victim of the wrong they were designed to address—white women in some feminist frames, Black men in some antiracist frames—leaving Black women, immigrant women, and other women of color stranded in the gaps.

That argument would have been consequential even if it had stayed within legal scholarship. But Crenshaw has never acted like scholarship is a room you sit inside. Over the decades, she has built a career that moves ideas through institutions: law schools, research centers, advocacy networks, public campaigns, and media platforms that translate technical concepts into usable language. If “entrepreneur” sounds, at first, like an odd label for a legal scholar, it becomes more plausible the closer you look. Her work does not only interpret the world; it has repeatedly built the vehicles through which an interpretation can travel.

Crenshaw holds appointments at Columbia Law School and UCLA School of Law, and her faculty biographies foreground a range of interests—civil rights, critical race theory, constitutional law, Black feminist legal theory—that form the intellectual ecosystem in which intersectionality was born. But to describe her significance as merely academic is to miss the larger pattern: she has helped create durable frameworks for how institutions, movements, and the public interpret harm.

To understand that pattern, it helps to start where she started: in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when civil-rights law had matured into a specialized field with settled doctrines and familiar narratives—and when a younger generation of scholars began arguing that those doctrines and narratives were, in important ways, insufficient.

From legal realism to racial realism—and the emergence of critical race theory

Crenshaw came of age professionally in a period when the achievements of the civil-rights era were being consolidated into legal standards, case tests, and institutional compliance regimes. Yet many scholars and practitioners recognized a paradox: the law’s victories did not automatically translate into structural transformation. Anti-discrimination frameworks often focused on intent, on overt exclusion, on explicit racial language. Meanwhile, inequality persisted through housing patterns, school financing, employment segmentation, and criminal legal systems that could reproduce racial hierarchy without announcing itself as racial.

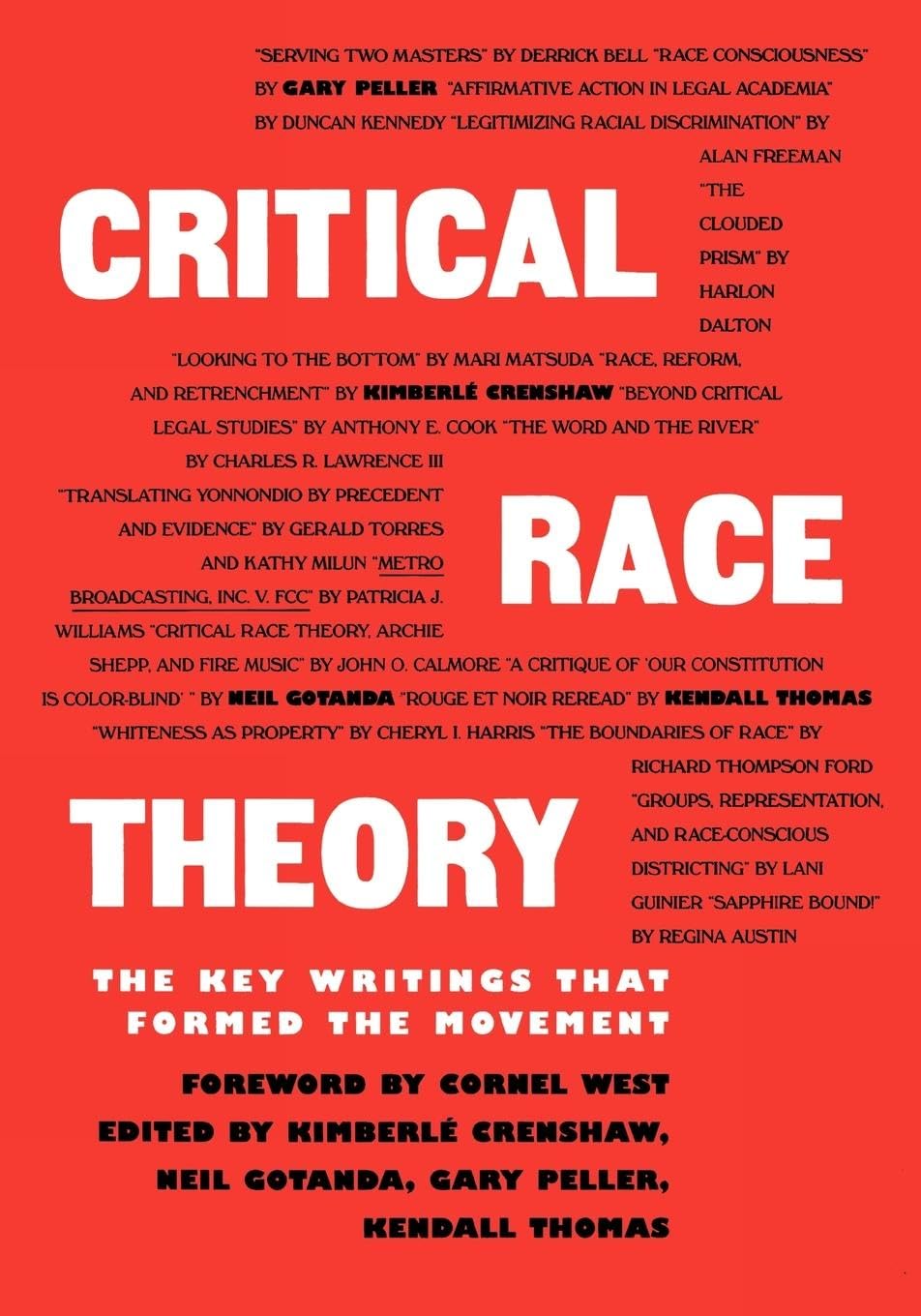

One major intellectual current responding to this paradox is Critical Race Theory, associated with a group of legal scholars who emphasized that racism is not merely aberrational but can be systemic—embedded in law and policy, reinforced by incentives, and normalized by institutional routines. Crenshaw is widely identified as foundational to this movement, and profiles of her career emphasize her role as an “architect” of the school of thought. The movement itself is often described as extending, in legal scholarship, a tradition of skepticism about formal neutrality: just because a rule is written in general terms does not mean its effects are general.

In that orbit sits Derrick Bell, whose work on “racial realism” and the limits of legal reform shaped many later arguments about why formal equality can coexist with deeply unequal outcomes. The point, in its strongest form, is not that law never matters, but that law can serve multiple masters. It can redress injustice; it can also rationalize it.

Crenshaw’s signature contribution—intersectionality—arrived as part of this broader effort to make the law’s blind spots visible. It also carried a distinct focus: Black women were not simply “double victims” of racism and sexism, and their experiences were not merely additive. They were produced by the interaction of institutions and narratives that treated “race” and “gender” as separate silos. The stakes of this claim were not theoretical. They were procedural: whether someone could successfully bring a claim, whether a court would recognize the injury, whether a movement would name the victim.

“Demarginalizing”: Intersectionality as a legal argument, not a slogan

When Crenshaw first advanced intersectionality, she did so in the grammar of doctrine and case analysis. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex,” published through the University of Chicago Legal Forum, is a work of legal reasoning that reads like a brief against a system that keeps asking the wrong questions. It critiques antidiscrimination doctrine that assumes discrimination is best understood along one axis at a time. In such a framework, a Black woman plaintiff might be asked to prove she was discriminated against “as a woman” or “as a Black person,” but not as a Black woman experiencing a particular form of exclusion that occurs precisely at that intersection.

The now-famous illustrative case—often summarized in interviews and educational materials—concerns Black women workers at an auto manufacturer whose experiences of discrimination were not legible to the court because the employer hired Black men and hired white women, leaving Black women uniquely excluded. In a system that treats “race discrimination” as something Black men can fully represent, and “sex discrimination” as something white women can fully represent, Black women become doctrinally invisible. That invisibility is not an accident; it is a structural feature of how categories are used.

Crenshaw’s argument was also aimed at political movements and feminist discourse. She claimed that even groups with emancipatory aims can replicate patterns of marginalization when they build their agenda around a single “typical” subject. When feminism centers the experiences of white, middle-class women, it can omit the ways race and poverty shape exposure to violence, employment vulnerability, or state intervention. When antiracist politics centers Black men, it can neglect the gender-specific forms that racism takes in Black women’s lives.

This is part of why Crenshaw has been insistent, for decades, that intersectionality is not merely a personal identity statement. It is a method for analyzing power—particularly institutional power—and understanding how policy can fail when it does not take compounding inequality seriously. In a widely circulated interview, she described it as “a prism” for seeing how forms of inequality operate together.

That insistence matters because the term’s afterlife has been turbulent. Once a concept becomes popular, it begins to operate as a kind of currency—spent for different aims, sometimes far from its original meaning.

When an academic term becomes a mass language—and a battlefield

The modern media environment does not treat ideas gently. It compresses them into talking points, politicizes them, turns them into litmus tests. Intersectionality is a textbook example of this. Over time, the term migrated from law reviews to activist discourse to mainstream journalism and popular debate. By the 2010s, it had become common enough to be described in explainer articles and to be debated as a symbol of a broader cultural shift.

With that migration came distortions. Some critics treated intersectionality as a demand that everyone adopt an ever-expanding set of identity labels. Others treated it as a kind of moral hierarchy. Crenshaw has repeatedly argued that these interpretations miss the point: intersectionality was coined to highlight structural vulnerability—to show how institutions and policies fail to account for people who experience overlapping disadvantages.

In 2015, Crenshaw wrote in The Washington Post that “intersectionality was a lived reality before it became a term,” and she warned that if women and girls of color remain “in the shadows,” something vital has been lost. The phrasing is characteristic: shadow, margins, erasure—these are not metaphors chosen for academic flair. They describe how institutions distribute recognition, and how that recognition determines whose injuries count.

This dual reality—an idea becoming mainstream and becoming misused—has been central to Crenshaw’s public role. She has become not only the originator of the concept but also, in effect, its steward: clarifying, correcting, and insisting on its practical stakes.

The cultural backlash has been intense. Intersectionality is often mentioned in debates about “identity politics,” diversity initiatives, and educational curricula. Crenshaw herself has been profiled in the context of political attacks on critical race theory, framed as a figure whose scholarship has been turned into a proxy for broader anxieties about race and power.

Her response has typically been to return the conversation to material outcomes: what policies do, whom they protect, whom they leave behind. That reflex—moving from abstraction to impact—explains much of her work beyond academia.

The African American Policy Forum and the craft of building an idea into an institution

If intersectionality is Crenshaw’s most famous intellectual contribution, her most entrepreneurial achievement may be the organizational infrastructure she has helped build to keep the concept anchored in real-world struggles. She is co-founder and executive director of the African American Policy Forum, an organization that has played a prominent role in bringing intersectional analysis to public policy debates and movement work.

The African American Policy Forum’s work illustrates a strategic insight: ideas do not travel on their own. They need vehicles—campaigns, reports, convenings, educational efforts—capable of translating theory into usable frames. Crenshaw has often operated at precisely that translation point, where the language of legal categories meets the demands of public storytelling.

One of the clearest expressions of this is the #SayHerName campaign.

#SayHerName: The politics of remembrance and the mechanics of visibility

By the mid-2010s, public awareness of police violence had surged, driven in part by viral video, grassroots organizing, and a media landscape that could no longer easily ignore deaths at the hands of the state. Yet Crenshaw and her collaborators pointed out a persistent pattern: the names that became emblematic were overwhelmingly male. That did not reflect reality; it reflected visibility.

#SayHerName was designed as a corrective—a campaign to insist that Black women who experience police violence and state violence are not footnotes. The African American Policy Forum describes the campaign as uplifting stories of Black women killed by police and providing analytical frames to broaden dominant conceptions of what state violence looks like.

Crenshaw’s approach here is consistent with her earlier scholarship: the fight is not only over policy but over the frames through which policy harms are recognized. If the public cannot name a category of victims, it becomes harder to demand remedies for them. If a movement’s most visible narrative excludes certain people, the exclusion can be replicated in policy priorities, funding, media attention, and collective memory.

A Columbia Magazine interview captures this logic through an anecdote about the origins of intersectionality itself—how the framework emerged from trying to describe a situation in which Black women were uniquely excluded by what appeared, on paper, to be inclusive hiring patterns. The same analytic move appears in #SayHerName: the issue is not that people consciously decided Black women’s deaths matter less; it’s that existing narratives and categories make it easier to see some victims than others.

In national coverage, the campaign has also been discussed in terms of political appropriation—how a phrase built to spotlight anti-Black gendered violence can be repurposed to mean something else entirely. An Associated Press report traced the phrase’s origins to 2015 and described Crenshaw’s objections to its co-optation in partisan contexts. (AP News) The episode illustrates a broader challenge for public intellectuals: once your language becomes powerful, it also becomes contestable.

Crenshaw’s insistence has been that the point of #SayHerName is not branding. It is analytic clarity—and, ultimately, structural accountability.

The Anita Hill moment and a career shaped by contested public truth

Long before #SayHerName, Crenshaw had encountered a different kind of public contest over gender, race, and credibility: the 1991 confirmation hearings involving Anita Hill and Clarence Thomas. Accounts of Crenshaw’s career often note her involvement in assisting Hill’s legal team.

Even without relying on dramatized versions of the hearings, the significance is clear: the Hill-Thomas episode was a national spectacle about sexual harassment, institutional power, and the ways race and gender shape whose testimony is believed. It forced the public to confront competing solidarities—feminist and antiracist—and exposed how quickly Black women can be pressured to choose between them.

This is precisely the kind of conflict intersectionality was built to diagnose: not only overlapping harms, but overlapping expectations of loyalty, representation, and narrative.

Crenshaw would later argue—in essays and public commentary—that the “false tension” between feminist and antiracist movements has repeatedly limited collective capacity to protect women of color. In other words, the country did not merely watch a confirmation hearing; it watched a rehearsal of a broader structural dilemma.

The scholar as translator: TED, media, and the public life of a concept

Crenshaw’s influence cannot be measured only in citations or faculty titles, though those are substantial. It also shows up in the way she has helped build a public vocabulary around structural injustice. Her TED talk, “The urgency of intersectionality,” is an example of a scholar adapting an academic idea for a mass audience without surrendering its seriousness.

That public translation is not purely educational. It is strategic. A framework only becomes politically useful when people can deploy it—when it becomes part of how advocates argue for resources, how journalists describe patterns, how policymakers anticipate unintended consequences.

Mainstream outlets have repeatedly turned to Crenshaw as an interpreter of intersectionality’s implications in electoral politics, feminism, and public policy. The Atlantic quoted her on the importance of new frames entering the political lexicon to address old problems. Profiles and interviews in other publications have emphasized how the term’s meaning changes when it “travels” beyond its originating context—sometimes losing specificity, sometimes gaining reach.

This tension—between reach and fidelity—has become one of the defining features of Crenshaw’s public life. She is celebrated as the originator of a widely used concept, and simultaneously tasked with correcting what the concept is not.

What intersectionality changes in practice: Policy, advocacy, and institutional design

To treat intersectionality as merely a moral posture is to miss its operational implications. In Crenshaw’s work, intersectionality often functions as a tool for diagnosing why a policy fails. If a domestic violence shelter requires documentation that immigrant women can’t safely provide, or if anti-discrimination law doesn’t recognize compounded exclusion, then a policy that seems universally protective in theory becomes selectively protective in practice.

This is why intersectionality has been invoked in contexts ranging from labor economics to education to criminal justice. It has become a way to argue that outcomes cannot be fully understood through single-variable analysis—particularly when institutions stratify people across multiple dimensions at once.

Yet Crenshaw’s own emphasis has remained anchored in a fairly specific claim: vulnerability is structured. It is not a personal trait; it is a product of systems. When a system uses categories to allocate protection, it can inadvertently define some people out of protection.

That claim becomes especially potent in the realm of policing and state violence. The #SayHerName report and related work argue that Black women face gender-specific forms of police violence, and that public silence around their experiences distorts our understanding of state power.

In other words: intersectionality isn’t simply about adding more identities to the story. It is about changing the story’s architecture so it can hold what reality contains.

The backlash: When critical race theory becomes a political symbol

In recent years, Crenshaw has become a central figure in the public battle over how race is taught, discussed, and legislated in the United States. Many conservatives have attacked “critical race theory” as a catchall for diversity training, historical analysis of racism, or any institutional effort to name structural inequality. Crenshaw and others have argued that these attacks often misrepresent what critical race theory is and what it does, turning a scholarly field into a political weapon.

This matters not only for reputational reasons but because it shapes educational policy, curriculum decisions, and the climate in which teachers and administrators operate. If a framework becomes taboo, it becomes harder to describe the realities it was built to illuminate.

Crenshaw has approached this backlash the way she approached the law’s blind spots: by arguing for precision. What does the framework actually claim? What evidence supports it? What outcomes are being produced by policies that pretend race is irrelevant?

In a Guardian interview and related coverage, she has been presented as a figure “at the heart of the culture wars,” precisely because her work insists that you cannot solve problems you refuse to name.

Influence, misreadings, and the burden of being the name attached to an era

There is a particular burden that falls on thinkers whose concepts escape their original domain. They become, in public imagination, the concept itself. Crenshaw is often introduced as “the woman who coined intersectionality,” as if her work begins and ends with a word. But her career is better understood as an extended project: to make structural inequality legible, and to create institutions that can act on what becomes legible.

Her influence shows up in multiple registers:

In academia, intersectionality has become a foundational framework across disciplines, shaping research agendas and teaching. In legal studies, it has reoriented how scholars interpret antidiscrimination law’s limitations.

In activism, it has offered a language to argue that movements cannot treat inclusion as a secondary concern. It has helped legitimize claims from those who have historically been asked to wait their turn—Black women, queer people of color, immigrant women, disabled women of color, and others whose needs can be sidelined by “single-issue” prioritization

In policy, it has provided a way to critique programs that claim universality while producing uneven results. It can be used to ask: who benefits, and who is missing? What assumptions about the “typical” subject are baked into the design?

And in culture, intersectionality has become a contested symbol—praised as a necessary corrective, derided as jargon, invoked as shorthand for political tribes. That cultural life is not always flattering, and it is not always accurate. But it is evidence of reach.

This is why some profiles of intersectionality describe it as a theory that “went viral,” and why discussions of its popularization often focus on the gap between what Crenshaw meant and what the public hears.

The gap is not simply semantic; it is political. If intersectionality is reduced to an accusation—if it becomes a way to police language rather than diagnose institutions—its power as an analytic tool can be diminished. Crenshaw has repeatedly warned against this reduction, emphasizing that the concept is about power and policy, not personal purity.

Re-centering the point: Why her work remains hard to replace

It is tempting, in a moment of cultural fatigue, to treat intersectionality as yesterday’s framework—something that has been argued over enough, meme-ified enough, diluted enough to be obsolete. But the conditions it was built to address have not disappeared. If anything, the modern governance environment—with its reliance on algorithms, data categories, and compliance checklists—can reproduce the same problem in new forms: systems that recognize only what they are built to measure.

Intersectionality’s enduring relevance lies in the way it challenges institutional design. The concept forces a confrontation with the fact that categories are not neutral. They are tools that distribute attention and resources. When institutions use categories too rigidly, they can mistake partial inclusion for full justice.

Crenshaw’s scholarship and activism have functioned as a kind of diagnostic pressure on American liberalism: a reminder that inclusion cannot be declared; it has to be engineered. Her work asks institutions to consider not only who is present, but who can’t get in—and why.

That’s also why she has continued to be involved in developing research centers and policy-oriented initiatives that aim to keep intersectional analysis connected to governance questions. Her faculty roles and affiliated centers emphasize the institutionalization of the field, not just its publication.

The paradox of success: When a concept becomes common, the original harms can still persist

One of the most sobering implications of Crenshaw’s career is that conceptual victory does not guarantee material victory. Intersectionality is widely known; the lives it was meant to make visible are still too often rendered invisible by institutions that prefer simpler stories.

Consider the ongoing struggle to ensure that Black women’s experiences of state violence are treated as central rather than peripheral. The #SayHerName campaign exists precisely because public discourse still defaults toward narratives that render some victims iconic and others obscure.

Or consider how debates about education and history can treat discussions of systemic racism as optional, controversial, or inappropriate—despite the persistence of disparities that are difficult to explain without structural analysis. Crenshaw’s work remains a rebuke to the idea that neutrality is enough.

In a sense, the most important part of her legacy is not the word itself. It is the disciplined habit the word represents: to ask who is missing from the frame, and what systems produced that absence.

A legacy best measured in what becomes visible

Journalists often search for the clean summation: a person, a phrase, a “defining contribution.” In Crenshaw’s case, intersectionality is undeniably that. But reducing her to a single term risks replicating the very flattening her work critiques. Intersectionality is not a brand; it is a method. It is a way of reading institutions against their own claims of universality.

Her career—spanning elite legal academia, public policy entrepreneurship, and movement-facing advocacy—shows how a concept can be built into infrastructure. The African American Policy Forum, #SayHerName, public lectures, interviews, and essays have functioned as an ecosystem designed to keep intersectionality oriented toward real-world stakes.

There is also a deeper reason her story matters now. In an era when public discourse increasingly rewards simplification, intersectionality is an insistence on complexity that is not decorative. It is survival-level complexity: the difference between being protected by a policy and being overlooked by it; between being mourned publicly and being erased; between being able to bring a claim and being told your claim doesn’t fit.

Crenshaw has spent decades arguing that the people most at risk are often those the system cannot easily categorize. Her work is a demand that we improve the system’s vision—not by replacing categories with chaos, but by refusing to treat partial pictures as full reality.

That is not only a scholarly achievement. It is an entrepreneurial one: the construction of a framework robust enough to move through institutions, adaptable enough to travel across contexts, and sharp enough to keep returning us to a basic, uncomfortable question.

Who, exactly, is the law—and the nation—built to see?

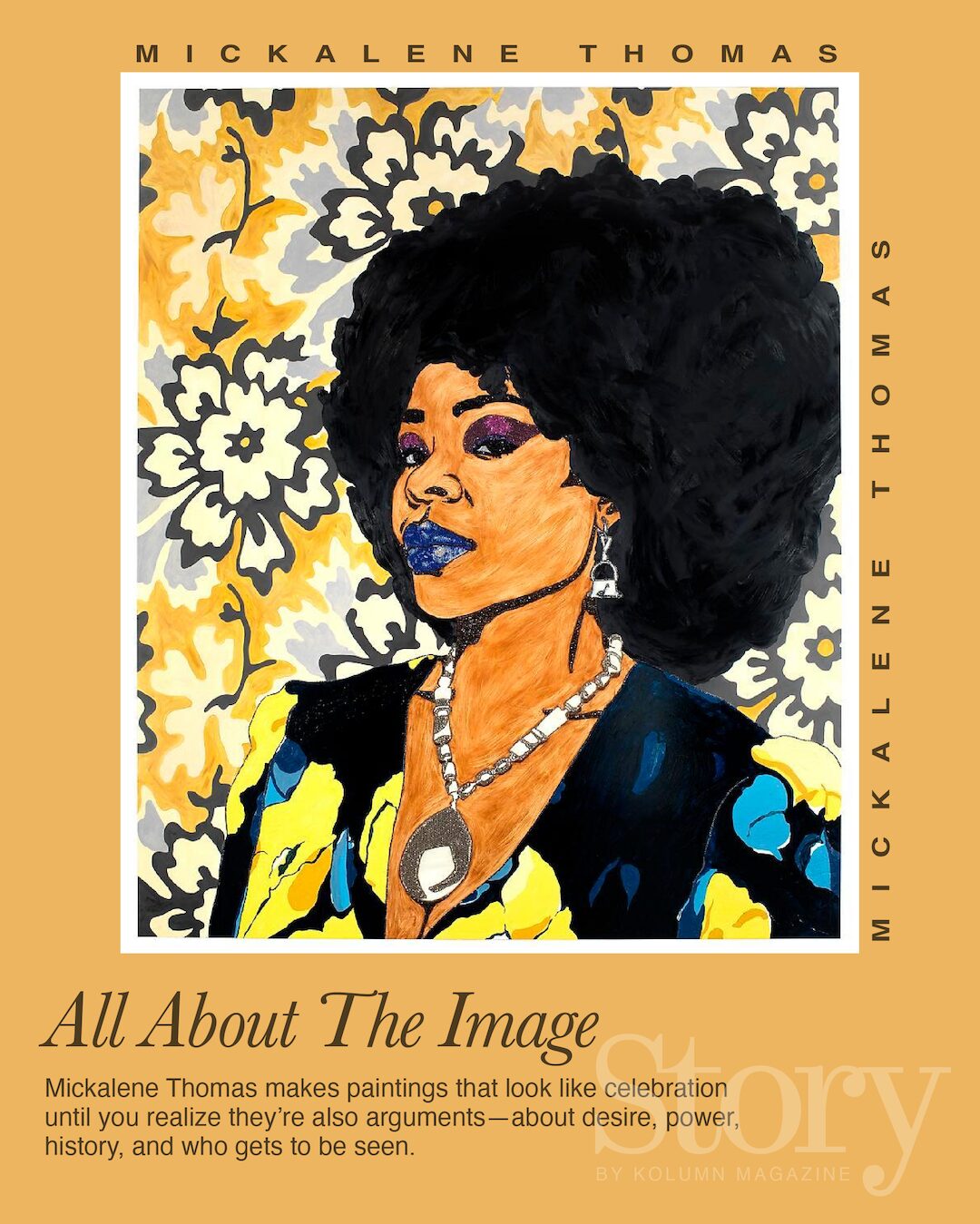

All About the Image