The purpose was always the stage, and the stage was always larger than the building.

The purpose was always the stage, and the stage was always larger than the building.

By KOLUMN Magazine

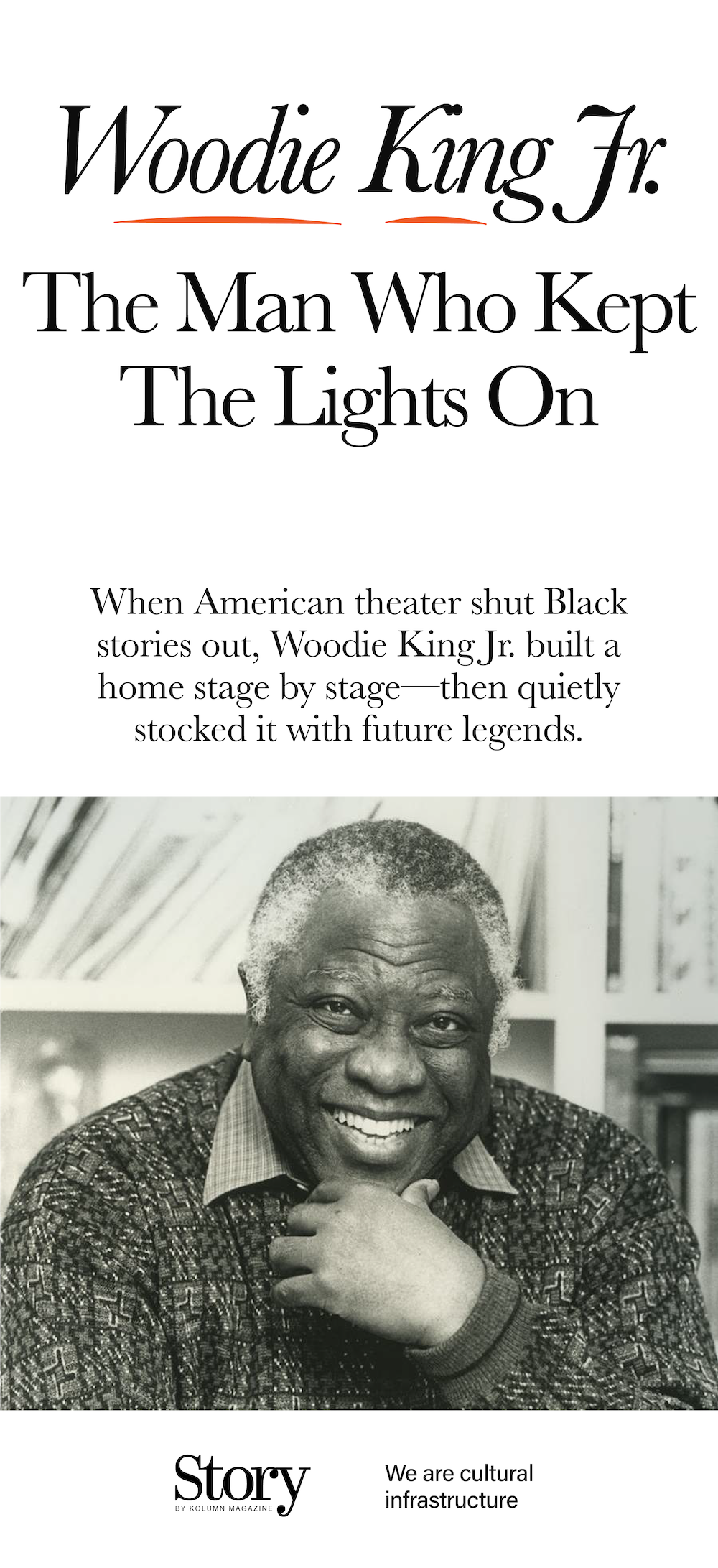

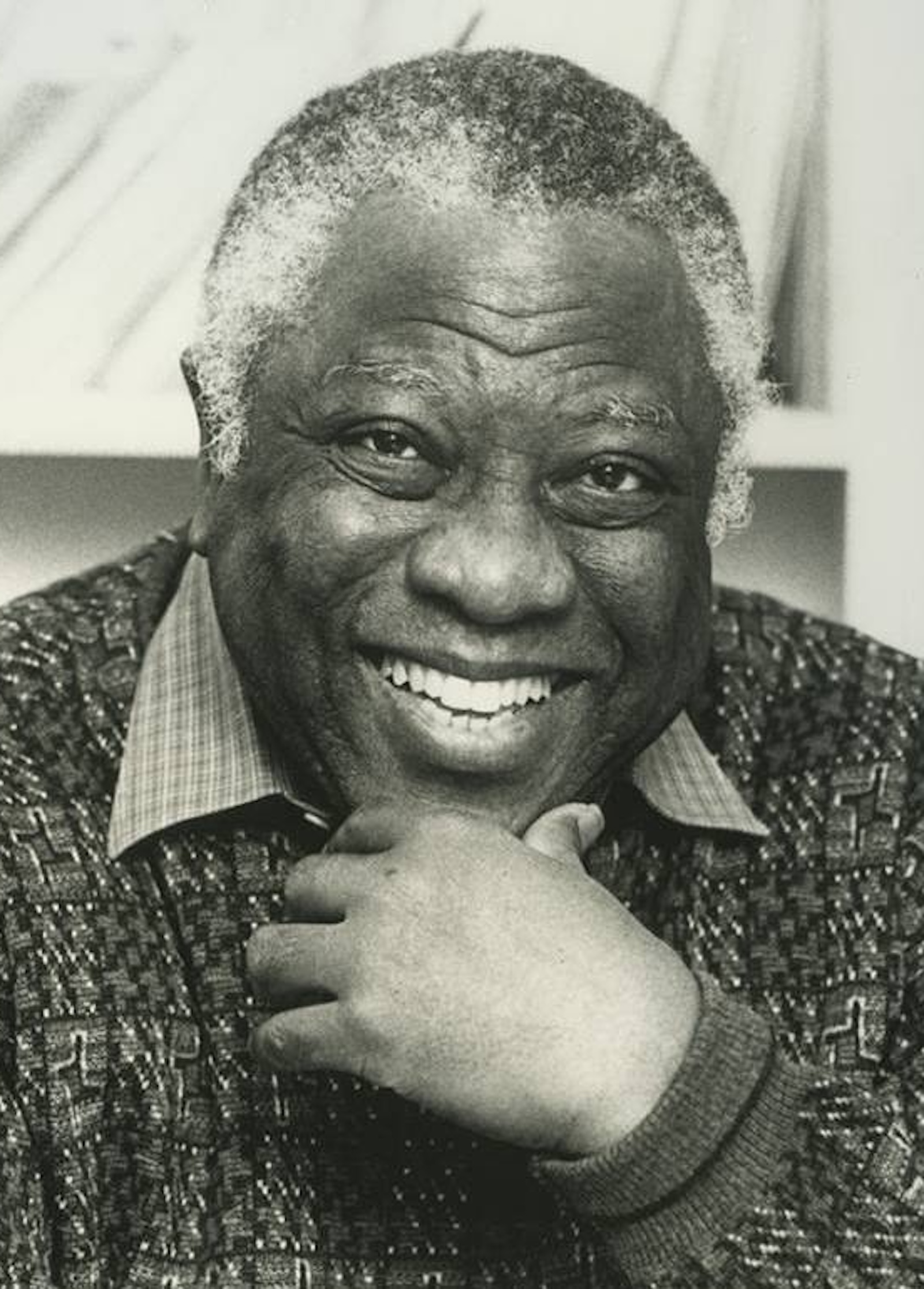

The quiet fact of him

There are artists who become famous by stepping into the spotlight and artists who become essential by building the spotlight, wiring it, hanging it, and then—when opening night arrives—standing just far enough back that someone else can be seen clearly. Woodie King Jr. belonged emphatically to the second category. For much of his career, the most consequential proof of his impact wasn’t a marquee with his name in lights, but the simple reality that the lights were on at all: a stage open to Black writers, Black directors, Black designers, Black technicians, and Black audiences in a city and industry that often treated those presences as optional, provisional, or “too specific” to be central.

In profiles and honors that arrived late by the usual standards of American recognition, King is repeatedly described as a builder—of institutions, of talent, of opportunity, of continuity. In 2021, when Broadway’s establishment finally attached a Tony honor to his life’s work, the citation didn’t just reward longevity; it described an ethos: a mission “to integrate artists of color and women into the mainstream of American theater” by training artists and presenting plays by writers of color and women to “integrated, multicultural audiences.” That sentence is the public, polished version of what King practiced in the daily friction of budgets, rehearsal time, venue politics, audience development, and the perennial question of which stories get treated as universal.

It is tempting to tell the story of Woodie King Jr. as a parable with a neat moral: a single man fights for representation, and the culture eventually catches up. But the more faithful story is messier and more instructive—less a straight line than a long, determined accumulation of decisions: to found a theater, to keep it alive, to place bets on writers before anyone else would, to insist that “Black theater” was not a genre but a world, and to treat the Black American community not as a niche audience but as a public with the right to complexity.

King died on January 29, 2026, after decades in which he produced, directed, mentored, and advocated—often simultaneously. The obituaries and tributes that followed used language that might sound ceremonial if it weren’t echoed by so many working artists: “godfather of Black theatre,” mentor, blueprint, builder. The question worth asking is what, exactly, he built—and why it mattered so much to Black America that his work has to be understood not merely as “theater history,” but as a form of cultural infrastructure.

Baldwin Springs to Detroit: The Great Migration in one life

King was born in Baldwin Springs, Alabama, in 1937, and moved with his family to Detroit when he was five—an intimate version of a massive demographic fact: the Great Migration that reshaped Black life, politics, labor, and culture in the 20th century. In Detroit, he graduated high school in 1956 and, like countless Black men in that era, took work at Ford Motor Company—the assembly line as both paycheck and narrowing horizon.

But the story of King’s early years is also the story of how Black cultural ambition persisted inside and alongside industrial life. He studied at the Will-O-Way School of Theatre on scholarship from 1958 to 1962 and wrote drama criticism for the Detroit Tribune during roughly the same period. The combination is revealing: he didn’t only want to perform; he wanted to evaluate, contextualize, and argue for the value of the work. Even then, the shape of his later career—part maker, part advocate, part historian—was visible.

In 1960, he co-founded the Concept-East Theatre in Detroit with the playwright Ron Milner, serving as manager and director into the early 1960s. This matters because it shows that his institutional instincts didn’t arrive after New York success; they preceded it. He was already learning what it took to put on work, develop audiences, and survive the fragile economics of the stage.

When he moved to New York in 1964, he entered the symbolic capital of American theater at a moment when Black theater was both politically energized and structurally constrained—full of voices, short on venues, perpetually negotiating with gatekeepers. In some accounts, he received a fellowship connected to theater study and administration; in others, the emphasis lands on his early work in arts programming and community-based cultural leadership. The specifics vary by source, but the throughline remains: King learned the administrative side of art because the administrative side often determines whether art exists.

An institution born from a historical memory

In 1970, King founded New Federal Theatre. The name was not a branding flourish. It was an argument about lineage.

King has said the company was created to honor the artists shaped by Works Progress Administration—the federal arts projects of the New Deal era that proved, at least briefly, that public investment could make culture a civic good. The word “Federal” carried both homage and challenge: a reminder that the state once recognized art as work, and a quiet rebuke to an America that would later treat arts funding as an indulgence rather than a public necessity.

The mission, as presented in the Tony recognition and repeated in later writing, is explicit: integrate artists of color and women into the mainstream by training and by producing plays that “evoke the truth” through artistic recreations of lived experience. The phrasing is important. It does not promise assimilation. It promises integration without erasure—entry without dilution.

That distinction becomes clearer when you look at the work that moved through New Federal Theatre’s doors. King’s career is often summed up in a number—more than 400 plays brought to life, according to an interview in American Theatre—but the more illuminating measure is the kind of repertoire he treated as necessary. He did not build a theater to prove Black artists could do what white institutions already valued. He built a theater to stage what those institutions often refused to value in the first place: plays that were formally adventurous, politically sharp, emotionally unsparing, and unapologetically rooted in Black experience—along with the experiences of women and other marginalized communities.

The producer as translator: Making the “unclassifiable” legible

In one of the most vivid accounts of King’s role in American theater, he is portrayed as someone who could spot the musicality inside a mess of pages and then help a writer become heard without sanding off the edges. This is a particular kind of talent: the producer as translator, not in the sense of changing a work into something safer, but in the sense of finding the conditions under which a new form can be recognized as itself.

Consider the three works highlighted in that account as emblematic of King’s taste and courage.

One is “The Taking of Miss Janie” by Ed Bullins, a piece described as violent and bracing, a parable about race, rape, and wishful thinking—political without being neat. Another is “The Dance and the Railroad” by David Henry Hwang, an elegiac drama about Chinese laborers building the transcontinental railroad, commissioned by New Federal Theatre and later staged at The Public Theater. The third is the work most closely associated with King in the public imagination: “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When The Rainbow Is Enuf” by Ntozake Shange—a genre-defying “choreopoem” that fused poetry, music, dance, and drama into a communal act of witnessing.

Each of these works, in a different way, demonstrates King’s significance to the Black American community: he supported plays that did not ask permission to be complex. Black life, in this repertoire, is not a sociological problem to be solved; it is an interior world to be expressed. That is a political stance as much as an aesthetic one.

“For colored girls”: The New Federal Theatre moment that became a national one

If you want to understand Woodie King Jr.’s knack for changing American theater without always receiving credit for the change, study the early life of for colored girls.

A The Washington Post review of Shange’s later work recounts a version of the origin story that feels almost mythic: Shange arrives in New York in 1975 with poems, reads and dances them in cafes with her friend Paula Moss, and then King “whisks” her into a new understanding—what she has written, he tells her, is a play. He produces the nascent work at New Federal Theatre; patrons line up around the block; then Joseph Papp sees it and brings it to the Public Theater and then to Broadway.

This chain of events matters not just because of the work’s eventual fame, but because it reveals King’s function in the ecosystem: he was the early-stage institution, the place where something new could take its first full breath. Broadway is often treated as the beginning of legitimacy. In this story, Broadway is downstream.

The Broadway production’s original cast list reads like a roll call of artists who would shape Black performance culture, even if their names are not always household ones outside theater circles. Playbill documents the original Broadway cast as including Trezana Beverley (Lady in Red), Laurie Carlos (Lady in Blue), Risë Collins (Lady in Purple), Aku Kadogo (Lady in Yellow), Janet League (Lady in Brown), Paula Moss (Lady in Green), and Shange herself (Lady in Orange). The piece ran for hundreds of performances and entered the canon as both artwork and intervention—a sustained public articulation of Black womanhood that made space for pain, humor, desire, rage, and solidarity.

What is sometimes forgotten is that the choreopoem’s endurance is also an institutional story: a work like this needed a producer willing to recognize the form before it had a name that the mainstream could comfortably market. King did not merely present a play; he helped the culture learn how to watch it.

The “For Colored Girls” story also connects King to a broader conversation about Black theater’s power to shape American art forms. A 2022 The Guardian piece on the play’s revival emphasizes the work’s lasting resonance and its insistence on “witness and recognition,” framing it as cannon-creating—a foundational text that changed what theater could hold. That language echoes what Black audiences already knew: some works don’t just entertain; they reorganize the cultural imagination.

The actors he helped launch—and what “launch” really means

When people attempt to summarize New Federal Theatre’s legacy quickly, they tend to list names. These lists can feel like a publicity strategy—famous alumni as proof of value. But in King’s case, the names are less about bragging rights than about the reality of a pipeline.

Accounts tied to the Tony honor and coverage of his recognition describe New Federal Theatre as an early home for performers who would go on to wider fame, including Morgan Freeman, Phylicia Rashad, Denzel Washington, Samuel L. Jackson, LaTanya Richardson Jackson, Debbie Allen, and, in a later generation, Chadwick Boseman and Issa Rae.

What does it mean for a theater to be an “early home” for people who later become icons? It does not mean King minted their talent. It means he provided conditions under which talent could become legible to an industry that often refuses to see Black excellence until it is impossible to ignore. He provided the first professional rooms, the first serious expectations, the first audiences primed to listen, and—crucially—the first validation that an artist’s full self did not have to be negotiated away to be employable.

The St. Louis American obituary includes a line that captures the emotional reality of this mentorship through the words of Freeman: “He nurtured us. He pushed us… He made us believe we had something to say — and that the world needed to hear it.” It’s not the language of a casual professional acquaintance. It’s the language of an artist describing the person who helped turn vocation into conviction.

In a Black American context, this kind of mentorship has special stakes. Because Black artists have often been asked—implicitly or directly—to perform legibility for white audiences, a Black-led institution can become a counter-space where the task is not to explain oneself but to deepen one’s craft. King’s significance lies partly in the fact that he treated Black audiences as discerning and Black artists as responsible to those audiences, not as ambassadors to an external world.

“The Taking of Miss Janie”: Controversy, complexity, and the refusal to simplify

To write about King honestly is to acknowledge that his devotion to Black theater did not always align with ease or consensus. Some of the works he championed were volatile by design. The Taking of Miss Janie is one of them.

While broad summaries of the play often speak in generalities—race relations, youth politics, a decade’s worth of ideological struggle—coverage of New Federal Theatre’s later revival underscores that the original 1975 production carried a particular charge and a particular memory. Backstage reported on a post-performance discussion in which original cast members were brought back to speak about the 1975 run; one original cast member, Adeyemi Lythcott, recalled that the original run was cut short due to venue-related issues. Even this small detail is instructive: Black theater history is full of brilliant work interrupted by structural fragility—leases, funding, real estate pressure, institutional neglect. Survival is part of the artistry.

What King’s choices reveal is not that he chased controversy for its own sake, but that he understood theater as a place where the Black community could wrestle with itself in public—without outsourcing the argument. Plays like Miss Janie challenge any assumption that “community-centered” work must be comforting. Sometimes community-centered work is exactly the opposite: a staging of harm, conflict, power, sex, ideology—the things communities must confront to evolve.

That willingness is a form of respect. You do not give a people only the stories you think they can handle. You give them the stories that tell the truth about what they have handled.

“The Dance and the Railroad”: the expansiveness of King’s “Black theater” vision

Although King is rightly framed as a cornerstone of Black American theater, his repertoire also demonstrates that he did not confuse Black liberation with narrowness. The commissioning and staging of The Dance and the Railroad shows a producer with an expansive understanding of solidarity and American history.

The play, written by David Henry Hwang, depicts Chinese railroad workers in a labor camp in the 19th-century American West and premiered as part of a commission by New Federal Theatre before moving to the Public Theater. The original production included Hwang’s story under the direction of actor John Lone, with Lone and Tzi Ma in the cast.

Why does this belong in a story about King’s significance to Black America? Because it clarifies that his project was not the building of a silo; it was the building of an alternative center—one where artists of color could make work about their histories without asking a white institution for permission. The New Federal Theatre’s mission, as repeated in the Tony citation, includes women and artists of color broadly. King’s vision made room for the idea that the American story is not singular, and that the institutions that claim universality must be contested not only by Black narratives but by a coalition of narratives that dismantle the myth of one default audience.

Directing as stewardship: Late-career work that stayed restless

A common failure in profiles of cultural builders is the temptation to treat late career as coda: a softer, smaller version of earlier battles. But King’s later work suggests he stayed restless—returning to writers associated with Black Arts traditions, revisiting canonical Black texts, and staging new versions of politically charged work.

A Theatre Communications Group profile of “Legacy Leaders of Color” notes, for example, that he won an NAACP Image Award for directing Checkmates in Los Angeles and continued directing at New Federal Theatre and related venues well into the 2010s, including works by Bullins and Amiri Baraka. A Primary Stages interview surveying his career references major titles associated with his company and his direction, including Universe, Robert Johnson: Trick the Devil, and Checkmates, among others, and frames New Federal Theatre as a long-running engine of Black theatrical life.

These mentions matter because they show that King didn’t freeze New Federal Theatre as a museum of “important” Black plays from a single era. He treated it as a living repertory—capable of revival, revision, and provocation.

Consider two later examples that illustrate how he used casting and direction to keep Black theater’s emotional range visible.

In 2014, New Federal Theatre staged The Fabulous Miss Marie with a cast led by Tonya Pinkins and Roscoe Orman, directed by King; coverage of the production lists a sizable ensemble around them, reflecting the institutional scale he maintained even in Off-Broadway contexts that often pressure Black companies into minimalism. And in the blues-inflected theatrical work around Robert Johnson: Trick the Devil, musician-actor Guy Davis notes that he starred in the Off-Broadway production at New Federal Theatre—an example of King’s interest in Black music history as dramatic material, not just atmosphere.

These productions may not have the mainstream recognition of For Colored Girls, but they reveal King’s deeper habit: he treated Black cultural life—blues, folklore, spiritual crisis, comedic survival—as stage-worthy at every scale.

Film as archival impulse: “Black Theatre: The Making of a Movement”

King’s career also includes filmmaking that functions as cultural preservation. His 1978 documentary Black Theatre: The Making of a Movement chronicles the emergence of a new Black theater shaped by civil rights and Black Arts-era consciousness, featuring major voices including Hansberry, Baraka, Ossie Davis, James Earl Jones, and Shange.

It is hard to overstate what it means for a Black theater producer to document Black theater as a movement rather than a series of isolated successes. Archiving is power. The dominant culture’s institutions tend to decide what is “history” by controlling what is preserved, taught, and circulated. King’s documentary is a counter-archive: a record that insists Black theater is not an add-on to American culture but a generator of American culture.

A later critical discussion of the documentary emphasizes that it remains in rotation decades after its production, suggesting that it functions not merely as a period piece but as a living text for understanding how art and activism braid together. For Black American communities, that braid has never been optional. When politics endangers life, art becomes both mirror and tool—an instruction manual for endurance, a rehearsal for liberation, a communal exhale.

The long fight for resources: King as advocate, not just artist

To talk about King’s significance without discussing arts funding and public policy would be to miss the material conditions under which Black theater survives.

A 1994 Washington Post article about an arts summit quotes King speaking as producing director of New Federal Theatre, arguing for the necessity of the National Endowment for the Arts and describing the need to build a new constituency—remarking that “leaning toward technology” could enhance that constituency. Even in this small archival trace, you can see a producer thinking strategically about audience, access, and survival.

This is another way King’s work intersects with Black community life. In many Black neighborhoods, cultural institutions do not have the cushion of generational wealth or stable donor classes. They are often asked to do more—train youth, provide community programming, archive history, host gatherings—while receiving less in the way of predictable funding. A theater like New Federal Theatre is not just an arts organization; it is a community resource. King’s advocacy for public arts support is therefore not abstract. It is about whether Black communities get to keep their cultural commons.

When he finally received Tony recognition, it was framed as belated acknowledgment of decades of “discovering talent.” The phrase sounds celebratory, but it also implies a critique: if the mainstream had been doing its job, King’s work would not have needed to be discovery-oriented. He had to create the mechanisms of recognition because the industry’s mechanisms were unreliable for Black artists.

The Tony honor: Recognition as correction, not coronation

In August 2021, the Tony Awards Administration Committee announced that it would present Tony Honors for Excellence in the Theatre to New Federal Theatre and Woodie King Jr., among others. Coverage at the time emphasized what many artists already understood: King’s name had not often appeared on Broadway marquees, but his work had shaped Broadway’s talent base and aesthetic possibilities.

It is worth lingering on the idea of “belatedly acknowledges,” a phrase used in one profile. Belated acknowledgment is not the same as honor; it is a correction of omission. When the culture belatedly recognizes a Black institution builder, it is often admitting—without fully stating—that the builder’s labor was necessary because the culture refused to do what it claimed it valued.

And yet, King’s response to such recognition, in the American Theatre interview, is framed less as victory than as a moment to reflect on the work: more than 400 plays brought to life, awards and nominations, a half-century of institutional persistence, and then—retirement from the artistic director role in 2021 after 51 years. That timeline is not just impressive; it’s almost defiant. Most theaters struggle to sustain a single decade without leadership change, financial crisis, or mission drift. King held a line.

Why Black America needed a New Federal Theatre

The deepest question behind this biography is not “What did Woodie King Jr. accomplish?” but “What did his community gain by his accomplishing it?”

Black American life has always produced theater in the broad sense: the church program, the street corner story, the sermon as performance, the dance floor as choreography, the living room as rehearsal hall. The problem has never been imagination. The problem has been institutions—places where imagination can become craft, and craft can become livelihood, and livelihood can become legacy.

New Federal Theatre functioned as such an institution. It gave writers a place to fail forward. It gave actors a place to develop technique in front of audiences that didn’t require translation of Blackness into a digestible product. It gave Black audiences a place to see themselves not as symbols, but as characters—contradictory, complicated, funny, wounded, tender, ambitious, spiritual, erotic, political.

And it gave the broader American theater something it often resists: accountability. By staging works that were formally innovative and politically urgent, King helped force the industry to expand its definition of what was “good,” what was “serious,” what was “marketable,” what was “universal.” When For Colored Girls moved from New Federal Theatre to the Public and then to Broadway, it didn’t just succeed; it changed the geometry of possibility.

There is also a more intimate community gain: the sense of permission. When Morgan Freeman says King made artists believe they had something to say and that the world needed to hear it, he is describing a psychological intervention in a society built to produce Black self-doubt. The stage becomes a counter-lesson: you are not marginal; you are central to the story.

The challenge of being the institution

A long career in Black theater building is also a long exposure to structural strain. Even sympathetic accounts of New Federal Theatre’s achievements hint at the background difficulties: the need to keep producing, to keep fundraising, to keep training, to keep audiences coming, to keep the mission from being diluted into a single “diversity” talking point.

When Backstage notes that an early run of The Taking of Miss Janie was cut short, it is not merely a trivia fact. It is representative of the precariousness that has historically hovered over Black theater spaces—venue politics, financial vulnerability, the fragility of leases and partnerships. When King advocated for the NEA, he was not performing a civic duty; he was fighting for oxygen.

And when the Tony honor arrived, it arrived in a world where the economics of theater had become even more punishing and where the language of “equity” could sometimes mask how slow resources move. Recognition does not pay rent. It does not guarantee board stability. It does not replace the daily labor of building.

This is why King’s significance cannot be separated from the Black American community’s broader pattern of institution-making: churches, fraternities and sororities, mutual aid societies, newspapers, colleges, civic clubs, music venues, beauty salons, barbershops—spaces that do more than their stated purpose because Black life has often been forced to build parallel infrastructure. New Federal Theatre belongs to that lineage. It is not only art; it is a community technology.

The canon as living thing: What he leaves behind

When King is called a “Renaissance Man of Black Theatre” in retrospective accounts, the phrase can sound like a compliment that flattens as much as it honors. Renaissance implies breadth—producer, director, filmmaker, actor, educator—but the more accurate description might be steward. King stewarded a canon that mainstream theater did not reliably steward for Black people.

A canon is not simply a set of famous titles. It is the relationship between titles and institutions: what is taught, revived, reviewed, funded, toured, archived. King’s genius was to treat Black theater not as a set of occasional breakthroughs but as a continuous practice—one that deserves the same infrastructure that white theater has often taken for granted.

His work also suggests a corrective to a persistent American misunderstanding: that Black culture exists primarily to be consumed. King’s New Federal Theatre insisted that Black culture is also a site of production—of training, of experimentation, of argument, of mourning, of joy, of critique, of spiritual inquiry. It insisted that Black audiences deserve work that is not simplified.

And perhaps most importantly, it insisted on time. Fifty-one years of running a theater company is an insistence on time in a nation that often treats Black initiatives as seasonal. Time is how craft deepens. Time is how mentorship becomes lineage. Time is how a community recognizes itself across generations.

The last word is a rehearsal note

In theater, legacies often get written as if they were monuments: fixed, finished, immune to revision. But Woodie King Jr.’s life resists monumentality because the core of his work was process. Rehearsal. Development. The long middle.

The most honest tribute, then, may not be to place him on a pedestal, but to understand his life as a set of repeatable practices: build a room; keep it open; invite the work that others fear; treat artists as capable; treat audiences as intelligent; archive what you can; advocate for resources; and when recognition comes, accept it without confusing it for the purpose.

The purpose was always the stage, and the stage was always larger than the building. The stage, in King’s hands, was a civic space—one where Black America could see itself fully, argue with itself honestly, and imagine itself forward.

That is not merely a theatrical accomplishment. It is a communal one.

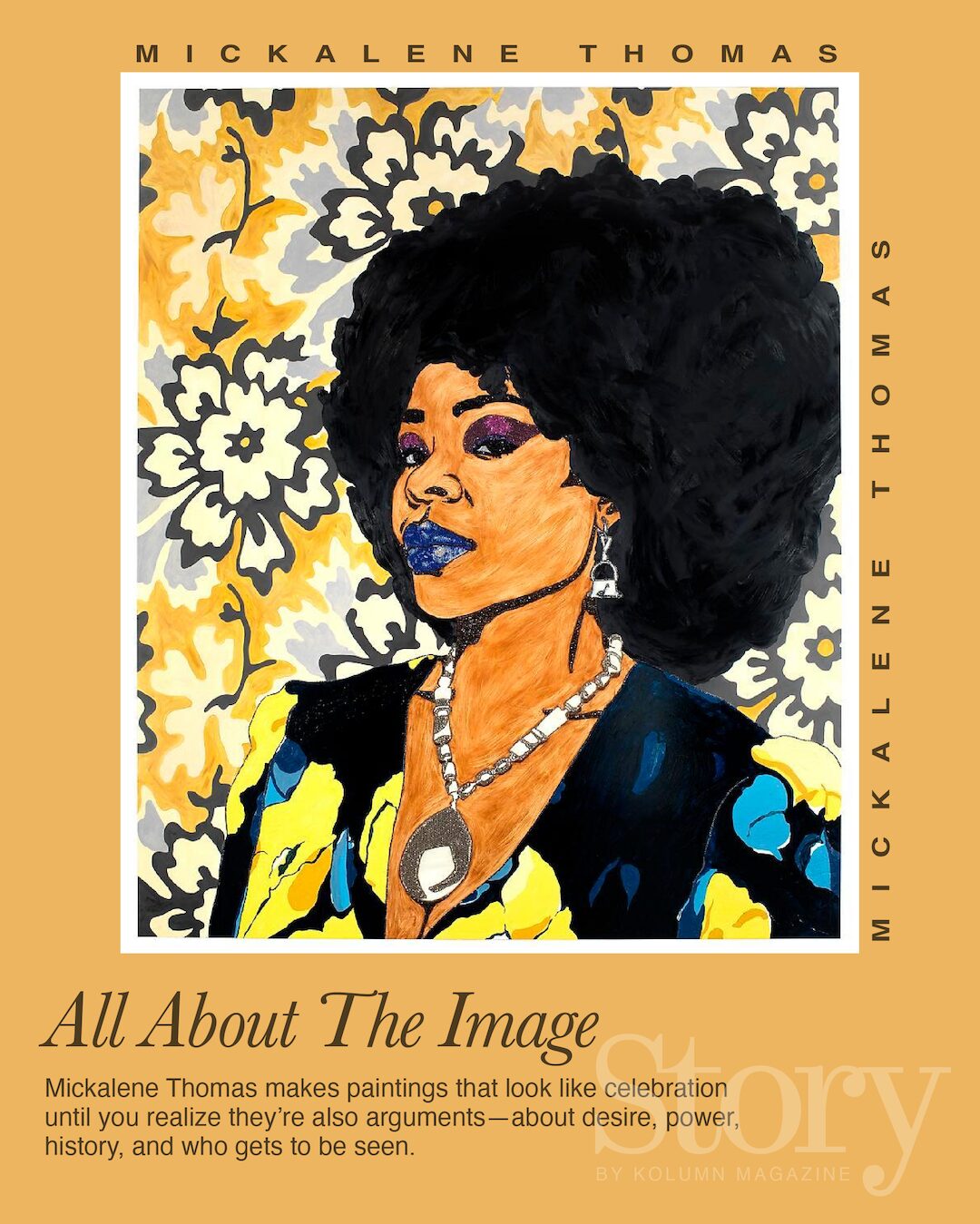

All About the Image