On April 23, 1954, Sportsman’s Park presented a version of America in which a Black rookie could hit a home run off a veteran pitcher and be recorded in a shared national archive. The city beyond the park was still shaping a version of America in which Black residents could be moved—by policy, by redevelopment authority, by “clearance”—and their displacement would be recorded as improvement.

On April 23, 1954, Sportsman’s Park presented a version of America in which a Black rookie could hit a home run off a veteran pitcher and be recorded in a shared national archive. The city beyond the park was still shaping a version of America in which Black residents could be moved—by policy, by redevelopment authority, by “clearance”—and their displacement would be recorded as improvement.

By KOLUMN Magazine

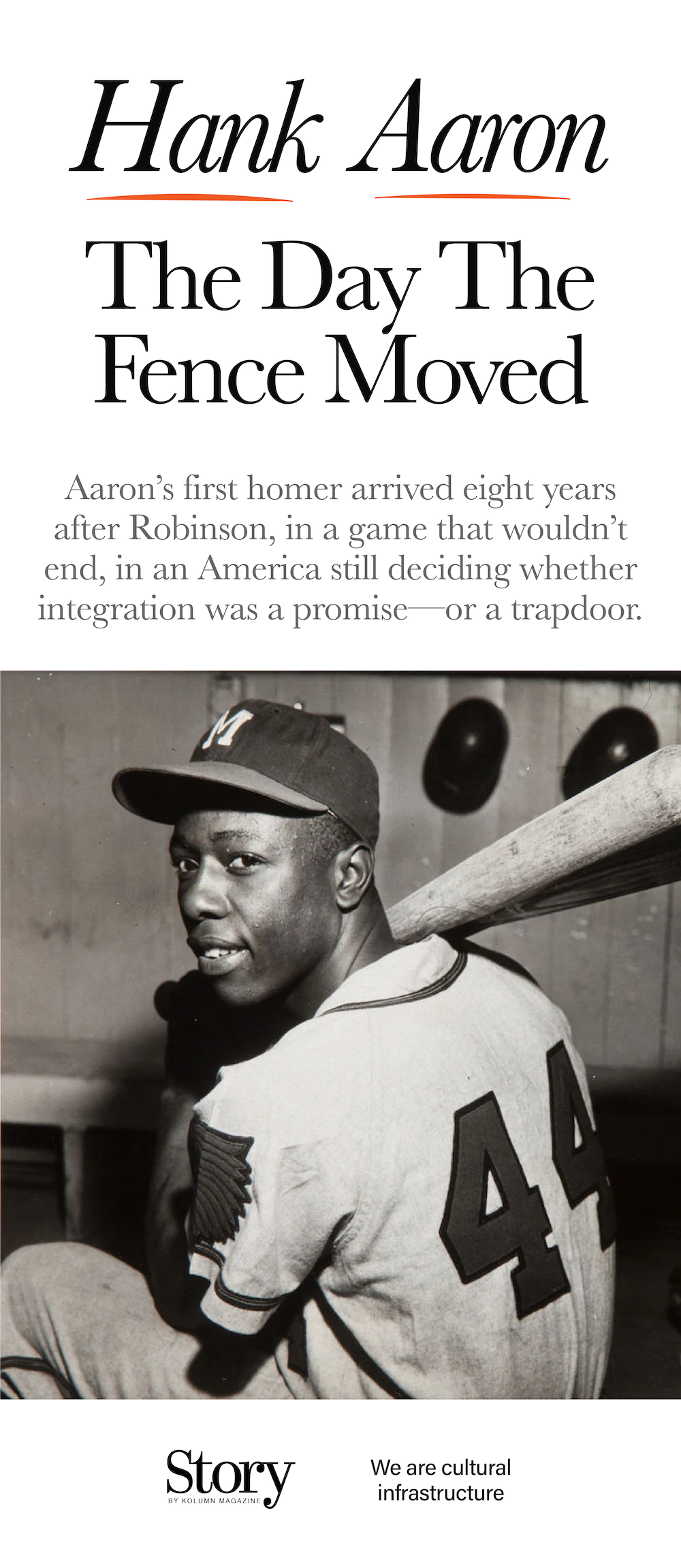

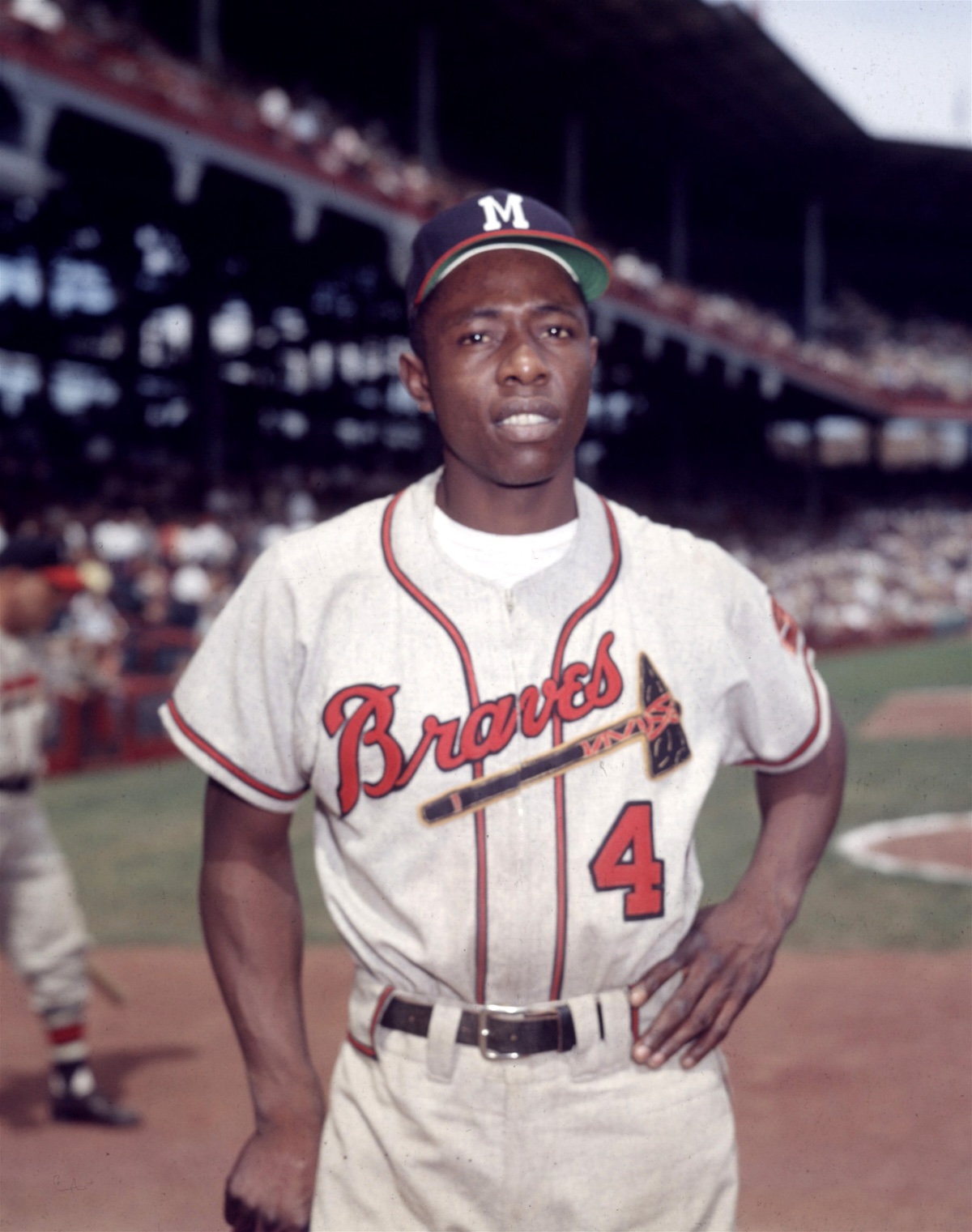

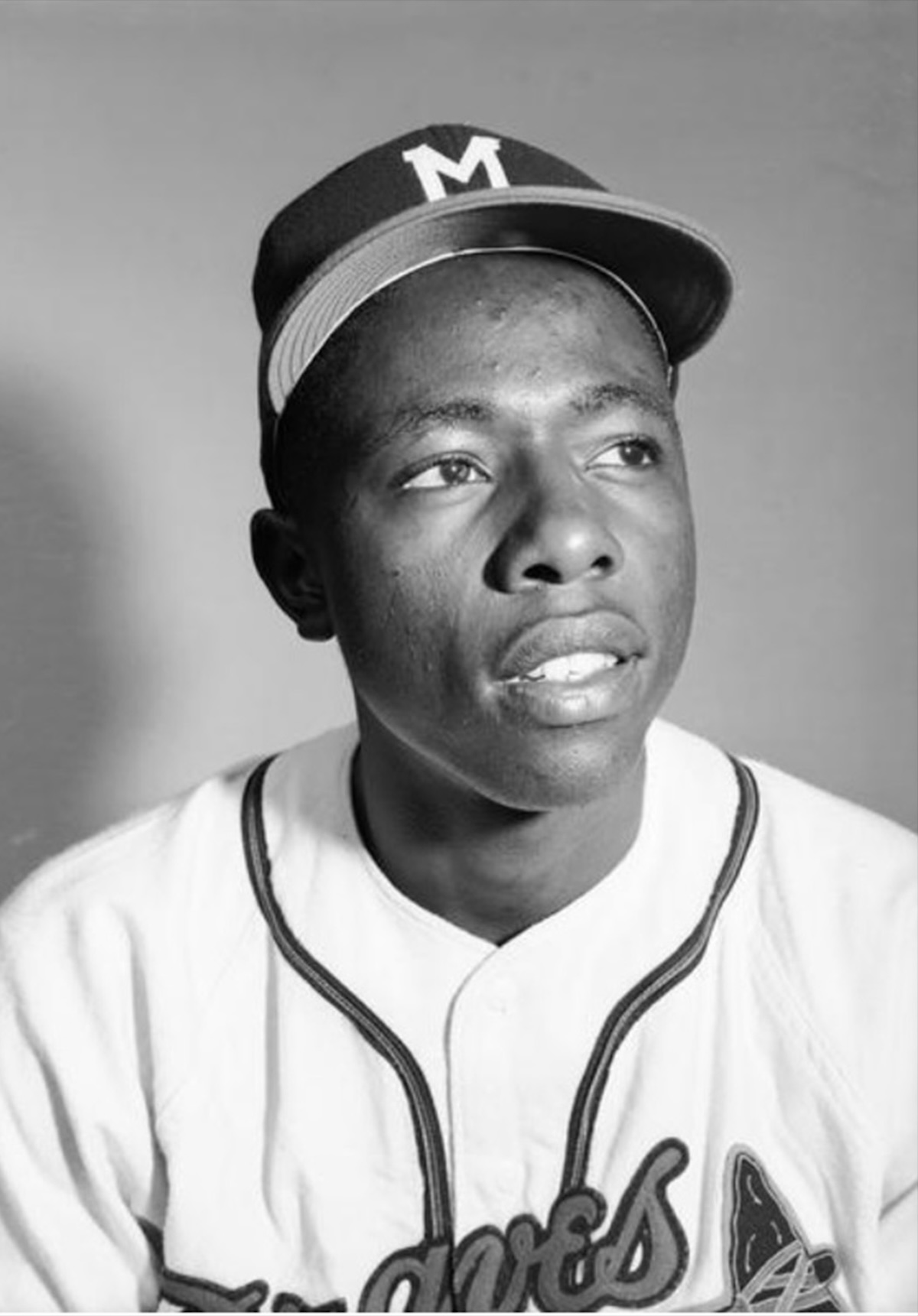

The first of Hank Aaron’s 755 major-league home runs did not arrive with fireworks. It arrived the way many American turning points do: on a weekday, inside a routine, with the world still pretending it is not changing.

It was Friday, April 23, 1954, at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis—sometimes already referred to as Busch Stadium in later records—when the Milwaukee Braves and the St. Louis Cardinals began a game that would not end until the fourteenth inning. The attendance was listed at 14,577, the final score 7–5, and the time of game 4 hours and 2 minutes. In the ledger, these details sit like rivets. In the lived day, the details were weather and muscle, nerves and patience.

Hank Aaron—twenty years old, in his seventh major-league game—was not yet “Hammerin’ Hank” to the country. He was a rookie outfielder playing because Bobby Thomson had broken his ankle and the Braves needed a replacement. The public didn’t know what it was watching. Plenty of the sport didn’t, either.

St. Louis, meanwhile, was a city that made history in multiple registers at once: the river and the rail, the factory and the church basement, the civic booster and the segregationist realtor. It was also the city that had recently given the nation one of the clearest legal expressions of how housing segregation functioned even when it dressed itself as private choice. Shelley v. Kraemer—a case arising from St. Louis—had reached the Supreme Court in 1948, and the Court held that courts could not enforce racially restrictive covenants because such enforcement was state action under the Fourteenth Amendment.

And yet: a decision is not a dismantling. After Shelley, the covenants didn’t vanish; they adapted. Exclusion continued through steering, financing, and “custom”—the kinds of rules that require no signage and leave no easy villain. The law could change the language; it couldn’t instantly change the market.

So if you want to understand the day Aaron hit his first home run, you have to place the swing inside its city. Not just inside a ballpark, but inside St. Louis in 1954: a place where modernist housing would soon be held up as solution and warning; where public projects were still entangled with segregation; where Black neighborhoods—dense with commerce and kinship—were already being studied as “slums” to clear.

That day at Sportsman’s Park, Aaron sent a ball over a wall. Around the stadium, St. Louis was still deciding where walls belonged.

St. Louis in 1954: A city of lines, visible and invisible

In 1954, St. Louis sat at the confluence of forces that shaped Black urban life across the Midwest: postwar industrial change, white suburbanization, and a civic planning ethos that believed demolition could be counted as progress.

Black St. Louis was not a footnote population. It was central to the city’s culture and economy—industrial labor, domestic work, small business, music, and church life. Neighborhoods like Mill Creek Valley—west of downtown—were not merely “housing stock,” though they would be described that way by officials. They were lived environments with corner stores, barbershops, social clubs, rented rooms, and the constant improvisation required when a city’s best opportunities are guarded by someone else’s keys.

The pressures on those neighborhoods were already mounting. Even before the wrecking balls of the late 1950s, St. Louis civic leadership was thinking in the vocabulary of “renewal”—a language that often treated Black density as pathology and Black proximity to downtown as a problem to solve. Mill Creek Valley would be targeted for massive clearance beginning in 1959, displacing roughly 20,000 residents, most of them Black—an outcome that makes the earlier planning years feel less like neutral governance than premeditation.

Public housing was part of this story, too—both aspiration and containment. Pruitt–Igoe, designed by Minoru Yamasaki and first occupied in 1954, rose just northwest of downtown on a site cleared under the same redevelopment logic. The project was legally integrated, but it became overwhelmingly Black in practice, and its early planning was entangled with a public-housing system that had long been segregated.

If you grew up in St. Louis, you learned the city’s lines the way you learned weather: not from a textbook, but from routine. Which neighborhoods were considered “good.” Which streets could turn hostile. Which landlords would rent. Which banks would lend. Which “for sale” signs were performative. You learned that the legal boundary—what the Constitution promised—was not the same as the practical boundary—what a realtor, a loan officer, or a neighbor could still enforce by quiet means.

And then baseball, the national pastime, placed a very public experiment on top of that civic reality: integration, playing out in front of crowds that included people who would never sit next to one another elsewhere.

April 1954 was not the deep past. It was the immediate prelude to Brown v. Board of Education, which would be decided on May 17. The country’s official posture was moving toward desegregation. Its local habits remained stubborn. On April 23, St. Louis embodied both truths at once.

Then Hank Aaron came to the plate.

The game, reconstructed inning by inning

What follows uses the documented line score and play-by-play reporting to reconstruct the game’s momentum and Aaron’s place within it—an inning-by-inning narrative built from the box score and contemporary baseball historiography.

First inning: Aaron arrives immediately, and the city answers back

Milwaukee did not wait. In the top of the first, the Braves collected four hits off Cardinals right-hander Vic Raschi and pushed across the game’s first run. Hank Aaron—batting sixth—singled in Danny O’Connell for an early RBI, a small event then and a foreshadowing now: the first RBI in what would become an all-time record total.

Then St. Louis responded with the confidence of a home club and the muscle of a lineup that still belonged to an older era of the National League. Gene Conley, the Braves’ rookie pitcher, issued early walks. The Cardinals turned patience into damage: Stan Musial singled to drive in two runs and reclaim the lead. In that same inning, Aaron was charged with an error in right field—another quiet reminder of how rookies are tested: not just by their strengths but by the timing of their mistakes. By the end of one inning, St. Louis led 2–1.

It’s tempting to read symbolism into everything: the Black rookie produces, then is punished. But what matters more is the condition the sport imposed on him—instant responsibility. Baseball integration did not offer a gentle on-ramp. It offered the majors and the judgment in the same breath.

Outside the park, St. Louis operated under its own instant judgments. A Black family could be perfectly qualified for a better apartment and still be told “no” without the courtesy of an explanation. Eight years after Shelley, the city still ran on the afterlife of covenant logic: the idea that whiteness could be protected by controlling space.

Second inning: Quiet frames, pressure accumulating

The second inning passed without scoring. In a normal game, such innings are forgettable. In a fourteen-inning game, they become foundational—time laid down like track. Pitchers settle. Hitters start to see patterns. The crowd recalibrates its expectations: perhaps this will be a quick Friday, perhaps not.

In 1954, St. Louis was similarly settling into a long contest about its own future. Public housing projects had begun to rise; modern planning promised efficiency; the city was fighting population loss to suburbs. But for Black St. Louisans, “planning” often arrived as an external force—something done to neighborhoods rather than with them.

The ballgame waited for its first rupture. So did the city.

Third inning: St. Louis expands, then reveals its volatility

In the bottom of the third, the Cardinals added two runs on a two-run home run by Ray Jablonski, stretching the lead to 4–1. The inning had basepaths and strategy—stolen bases, an intentional walk—and then one swing that made the careful decisions feel secondary.

That’s baseball’s recurring instruction: you can manage the margins, and then one event overturns your math.

St. Louis civic leaders would soon apply similar reasoning to neighborhoods: diagnosing “blight,” designing solutions, then assuming demolition would produce order. Mill Creek Valley, still intact in 1954, was already within the city’s field of vision as a candidate for radical “improvement.” The later redevelopment plan would describe slum clearance as the activity to be carried out—a sentence that reveals the order of operations: clearance first, community second.

Fourth inning: The Braves chip away; the game refuses to settle

Milwaukee answered in the top of the fourth when Johnny Logan hit a solo home run, making it 4–2. The Cardinals had asserted control; the Braves refused the verdict.

This is the early shape of the afternoon: St. Louis ahead, Milwaukee persistent, and a rookie in the middle of it—Aaron producing, learning, absorbing the game’s demand that you remain unbothered by uncertainty.

A similar persistence characterized Black St. Louis life in the 1950s: the endurance of institutions built because the wider city restricted access. Churches, fraternal organizations, neighborhood commerce, social clubs—cultural infrastructure before anyone called it that. These were survival systems, but they were also engines of joy.

And then “renewal” would arrive and treat those systems as obstacles.

Fifth inning: A held breath

The fifth inning was scoreless. In the park, you can feel this kind of inning: the crowd talking itself into patience, the small sounds rising—vendors, heckling, laughter—because nothing is happening that demands collective attention.

But something is always happening. Pitchers are working. Hitters are remembering. Fielders are shifting their feet, counting their chances. In a long game, the scoreless innings are not emptiness; they are preparation.

This, too, was St. Louis in 1954: the sensation of an ordinary city day masking longer-term forces. Pruitt–Igoe’s first occupancy was imminent; plans and funding moved through committees; the city was gearing up for the kind of redevelopment that would raze Black neighborhoods in the name of modernization.

Sixth inning: Aaron’s first home run, and the sound it made in a segregated city

Top of the sixth. One out. Hank Aaron homered to left field off Vic Raschi—a solo shot, his first in the majors—cutting the deficit to 4–3.

This is the moment that survives as milestone: the first of 755. The Hall of Fame notes it as the first homer in his seventh big-league game; SABR records the shot as the hinge moment in a marathon contest; the box score marks it with a simple “(1).”

In 1954, a Black rookie’s home run carried layered meanings depending on who was listening. For many white fans, it was baseball: a good swing, a promising kid. For Black fans—especially those living inside the city’s housing boundaries—it could register as something else: evidence, again, that excellence was not the issue. The issue was access.

St. Louis knew this tension intimately. It was the city of Shelley v. Kraemer, the city where the Supreme Court had said the courts could not enforce racial covenants. Yet the lived city still behaved as if separation was a civic virtue.

Aaron’s homer didn’t end the game. It tightened it. That difference matters. The first home run wasn’t a cinematic walk-off; it was a signal flare inside a longer fight. In the logic of the day, it said: we’re here, we’re close, we’re not leaving.

Seventh inning: The game shifts into a different kind of labor

No runs in the seventh. The pitchers and bullpens began to matter more than the starters. The game’s labor became distributed, the way city life is distributed: one person’s endurance depends on another person’s relief.

In St. Louis housing, relief was often promised by public projects and redevelopment schemes. But relief frequently arrived with strings: concentrated poverty, surveillance, isolation, and the displacement of older community networks. Pruitt–Igoe’s conception and early realities reflected this contradiction—sold as uplift, shaped by a system that had long segregated public housing and that still contained Black residents in practice even after legal barriers shifted.

Eighth inning: Still 4–3, and the crowd’s patience becomes a character

Another scoreless frame. In the eighth, a one-run game begins to feel like a dare. Every at-bat is a referendum. Every defensive play is a small verdict. Fans lean forward.

In midcentury St. Louis, a one-run margin resembles the way Black life was often made to feel: precarious. Not always in crisis, but always at risk of becoming one. The risk was not just interpersonal racism; it was structural. The built environment—where you could live, what you could buy, whether you could accumulate equity—was a system of margins.

Ninth inning: Milwaukee ties it, and the day becomes extra innings

Top of the ninth: the Braves tied the game 4–4 on a key single (as recorded in SABR’s reconstruction), pushing the contest into extra innings.

This is where the afternoon begins to resemble fate. Extra innings expose depth. Benches thin. Managers improvise. Players who expected to be done now have to find new reservoirs.

Cities, too, go into extra innings. St. Louis was already fighting to maintain population and tax base as suburbanization accelerated. It would respond, in part, by reshaping the city through large-scale redevelopment—efforts that would often treat Black neighborhoods as available land rather than lived places. Mill Creek Valley’s clearance beginning in 1959 would become one of the most searing examples.

Tenth inning: The tie hardens

No runs. The game becomes a loop: chance, denial, reset. In the stands, you can feel fatigue trying to become impatience.

In Black St. Louis, fatigue wasn’t a feeling; it was a condition. It came from overcrowding created by restricted housing options, from wages that lagged, from discriminatory access to suburban mortgages, from an ever-present awareness that the city’s “improvements” might arrive on your block as demolition.

Eleventh inning: Endurance becomes the point

No scoring again. In a long game, the scoreboard stops being the only story. The story becomes: who breaks first?

Hank Aaron keeps coming to the plate. He keeps running out to right field. He keeps being a young man inside a sport that is still learning how to treat Black players as ordinary participants rather than symbols.

Twelfth inning: Nothing happens—except the time passing

Still no runs. By the twelfth, the game has moved into the territory where the mundane becomes mythic simply because it persists. Fans who remain are no longer merely consumers; they’re witnesses.

The city, too, was accumulating witnesses. Former residents of neighborhoods like Mill Creek Valley would later describe what it felt like to watch a community erased—families dispersed, businesses destroyed, schools and churches dislocated. Those memories persist precisely because official language tried to make the destruction feel rational.

Thirteenth inning: A lead appears, then disappears

Top of the thirteenth: Milwaukee finally broke through with a solo home run to take a 5–4 lead.

Bottom of the thirteenth: St. Louis answered and tied the game 5–5, refusing to let the visitors escape.

This is the cruel symmetry of extra innings: the relief of advantage, followed immediately by its erasure.

In St. Louis, Black advances were often met with similar symmetry. Legal wins—like Shelley—could be followed by market evasions. New housing could be followed by new forms of containment. Public celebration could coexist with private exclusion.

Fourteenth inning: The rookie scores again, and the first homer becomes part of a bigger day

Top of the fourteenth: Milwaukee scored twice on a pinch-hit single with the bases loaded. The hit drove in Andy Pafko and Hank Aaron—the rookie scoring an insurance run that helped end the marathon. The Braves won 7–5.

This is an underappreciated feature of the day: Aaron’s first home run was not the only way he mattered in the final. He went 3-for-7, contributed early, homered in the sixth, and crossed the plate again in the fourteenth as the game’s closing argument.

A first home run is typically remembered as a singular event. That Friday in St. Louis, it was a chapter inside a longer, grinding proof: the rookie could endure. He could contribute in multiple ways. He could keep showing up.

That is not a baseball lesson alone. In 1954, it was a Black American lesson.

What St. Louis was doing the same year: “Renewal” as a second scoreboard

There is a reason St. Louis belongs in this story beyond the accident of venue. St. Louis, in the mid-1950s, was becoming an emblem of a particular American contradiction: the idea that modern planning could “solve” poverty by rearranging the poor.

Pruitt–Igoe was first occupied in 1954, built on land cleared under urban renewal logic, and promoted as a model of rational design. It would later become infamous—too often simplified as architectural failure rather than understood as policy failure, maintenance failure, and segregation’s long tail.

Mill Creek Valley would be targeted for massive clearance beginning in 1959, displacing roughly 20,000 residents, most of them Black. Later reporting and archival work underscores how this “renewal” functioned as removal: a neighborhood destroyed, people scattered, promises of redevelopment that did not arrive as advertised.

What does this have to do with a baseball game?

Everything, if you take sports seriously as a public ritual. On April 23, 1954, Sportsman’s Park presented a version of America in which a Black rookie could hit a home run off a veteran pitcher and be recorded in a shared national archive. The city beyond the park was still shaping a version of America in which Black residents could be moved—by policy, by redevelopment authority, by “clearance”—and their displacement would be recorded as improvement.

One archive protects a ballgame forever. The other allows a neighborhood to disappear.

KOLUMN’s mission—cultural infrastructure—means refusing to let that second archive stand alone.

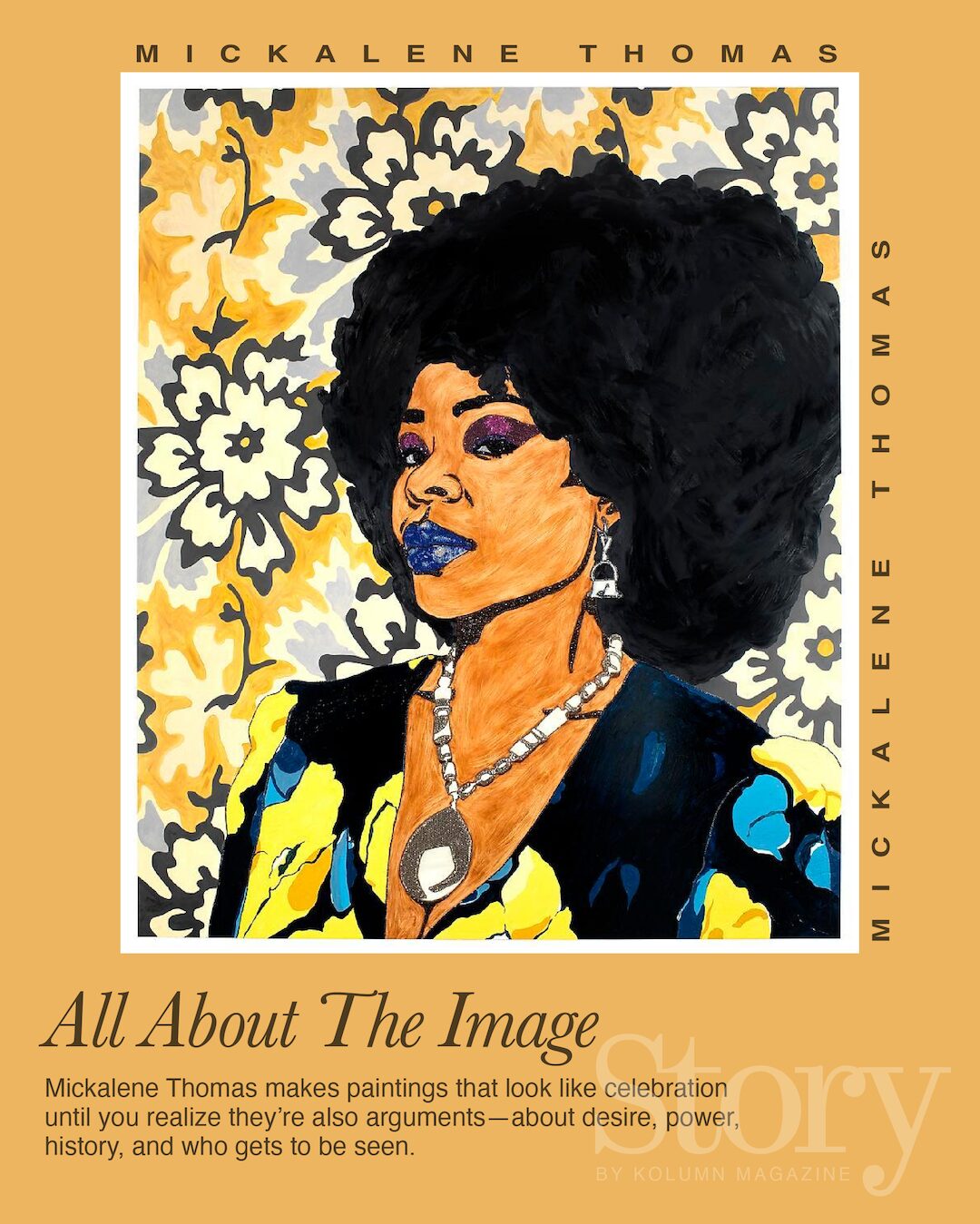

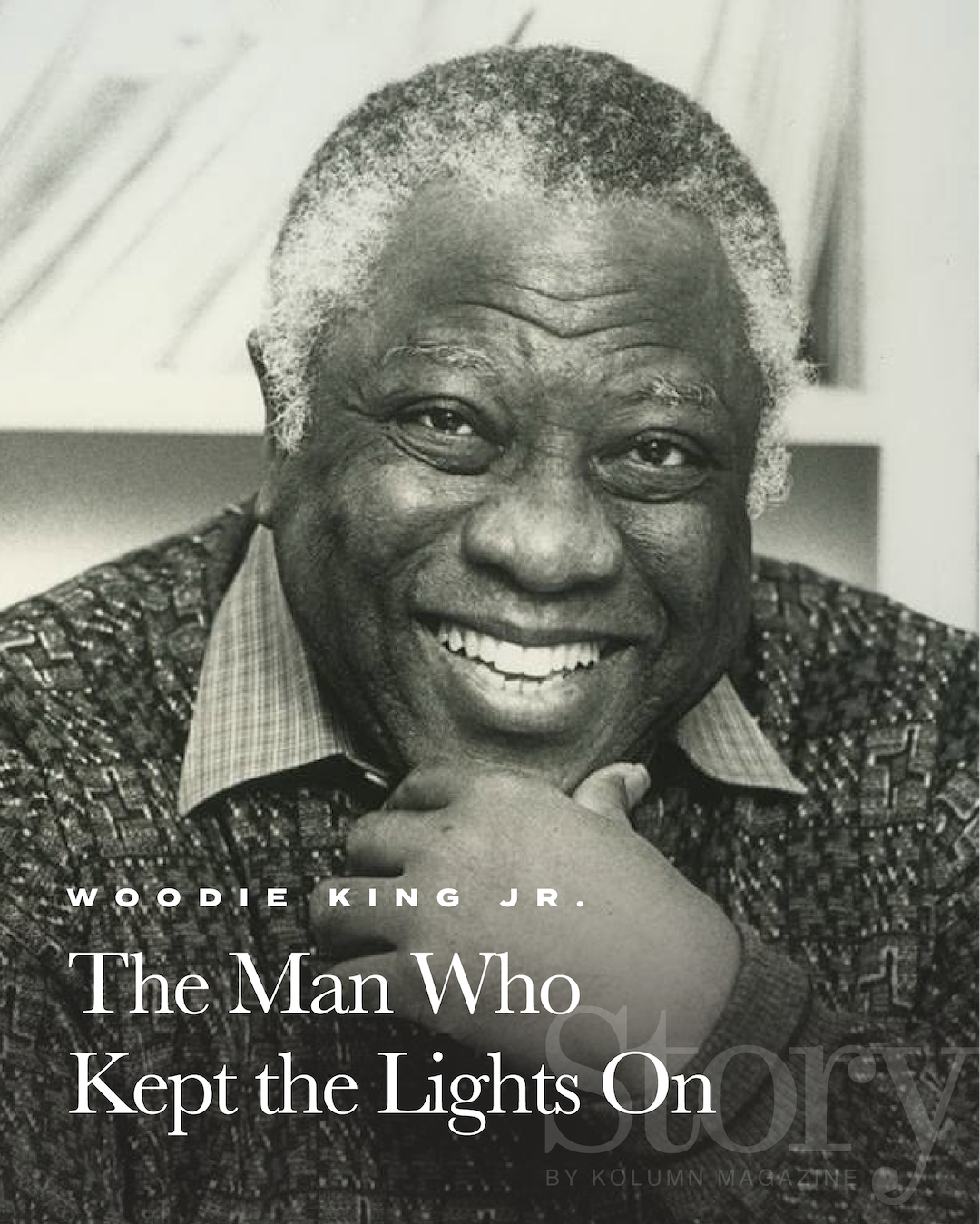

The Woman Who Put a Word to the Shadow