Thomas builds an environment that honors the way Black life is lived: not in isolated images, but in rooms, in playlists, in textures, in the accumulation of memory.

Thomas builds an environment that honors the way Black life is lived: not in isolated images, but in rooms, in playlists, in textures, in the accumulation of memory.

By KOLUMN Magazine

The first thing you notice is the surface

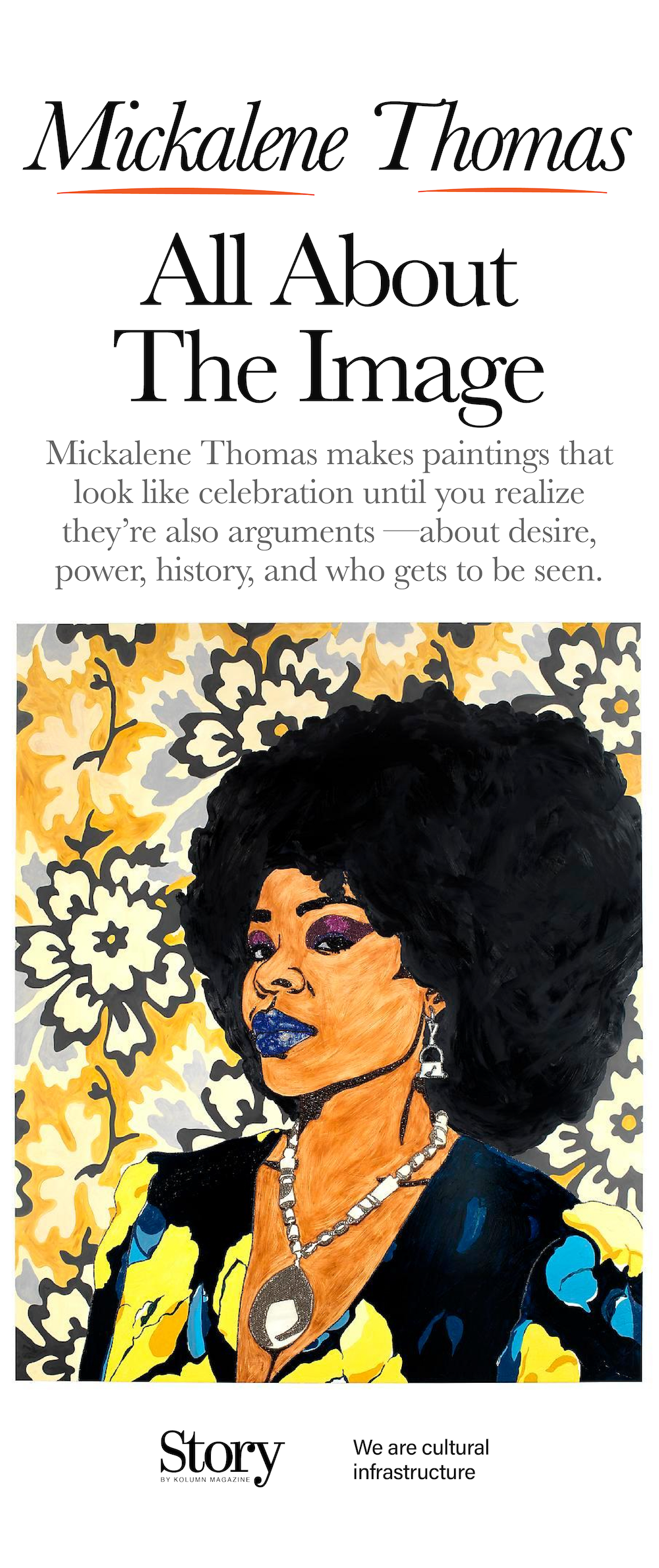

In reproduction, Mickalene Thomas’s work can look like a dare: color turned all the way up, patterns competing for dominance, bodies arranged with a deliberate theatricality, and then—almost impossibly—rhinestones, glittering like a formalwear version of pointillism. In person, the experience changes. The surface is not merely surface. It is an insistence, a kind of visual bassline. The rhinestones catch the light and return it, refusing the viewer’s desire to consume an image quickly and move on. You can’t really glance at a Thomas painting; the work turns looking into an event.

That insistence has become one of the artist’s signatures, but it is also one of her arguments. Thomas has built a career out of refusing the historical smallness that American culture has often tried to assign Black women—smallness of scale, smallness of narrative, smallness of interior life. Her portraits are large, staged, lush. They borrow from art history and popular culture at once, and they reassemble both into something new: an archive of Black femininity that is not “included” so much as centered.

In the past two decades, as museums and markets have accelerated their interest in Black figuration, Thomas’s work has often been discussed as a corrective—an antidote to erasure, a rebuttal to the museum’s long habit of placing Black subjects at the margins. That framing is true as far as it goes, but it can also flatten the complexity of what she does. Thomas is not only inserting Black women into the canon. She is interrogating the canon’s machinery: how “beauty” gets produced, how desire gets coded, how respectability and sexuality get policed, how intimacy becomes a battleground, and how the domestic space—so often dismissed as minor—can function as a studio, a stage, and a political site all at once.

Her recent touring survey, “All About Love,” has given audiences a chance to see the breadth of this project—painting, photography, collage, film, installation—less as a set of separate mediums than as one continuous attempt to answer a question: what does it mean to be visible on your own terms?

A childhood shaped by museums and a mother’s style

Thomas was born in 1971 in Camden, New Jersey, and raised in the orbit of cities where Black cultural life has always been abundant even when resourced unevenly: Newark, New York, the larger corridor of the Northeast. Biographical accounts emphasize the formative role of her mother, Sandra “Mama Bush” Bush, whose sense of style—dramatic, expressive, proud—would later echo in Thomas’s staged interiors and glamorous subjects.

If Thomas’s mature work luxuriates in pattern and presentation, it is not hard to see how those aesthetics can begin in a household where self-fashioning is a kind of everyday authorship. In interviews and institutional write-ups, she has spoken about being taken to arts programs and museums as a child, about learning to look early, to understand that images carry power and that museums, for all their authority, are also sites of omission. (Thomas has recalled youth experiences of visiting major institutions and noticing how little space existed for people who looked like her—an absence that becomes, in her adult work, a motivating pressure.)

Her education moved through multiple regions and disciplines before she arrived at the formal art pipeline that would later be cited as part of her credibility within elite art circles: Pratt Institute and Yale University appear frequently in bios, along with the mix of training and experimentation that precedes the clean story people like to tell about “breakthroughs.”

But the most emotionally enduring education, by Thomas’s own account, seems to have been the intimate kind: learning her mother’s contradictions, the distance and closeness between them, the way admiration can coexist with pain, the way a parent can be both muse and wound. Those tensions—love complicated by history, intimacy complicated by survival—are not “themes” in her work so much as conditions of its making.

Staging as a method, not a gimmick

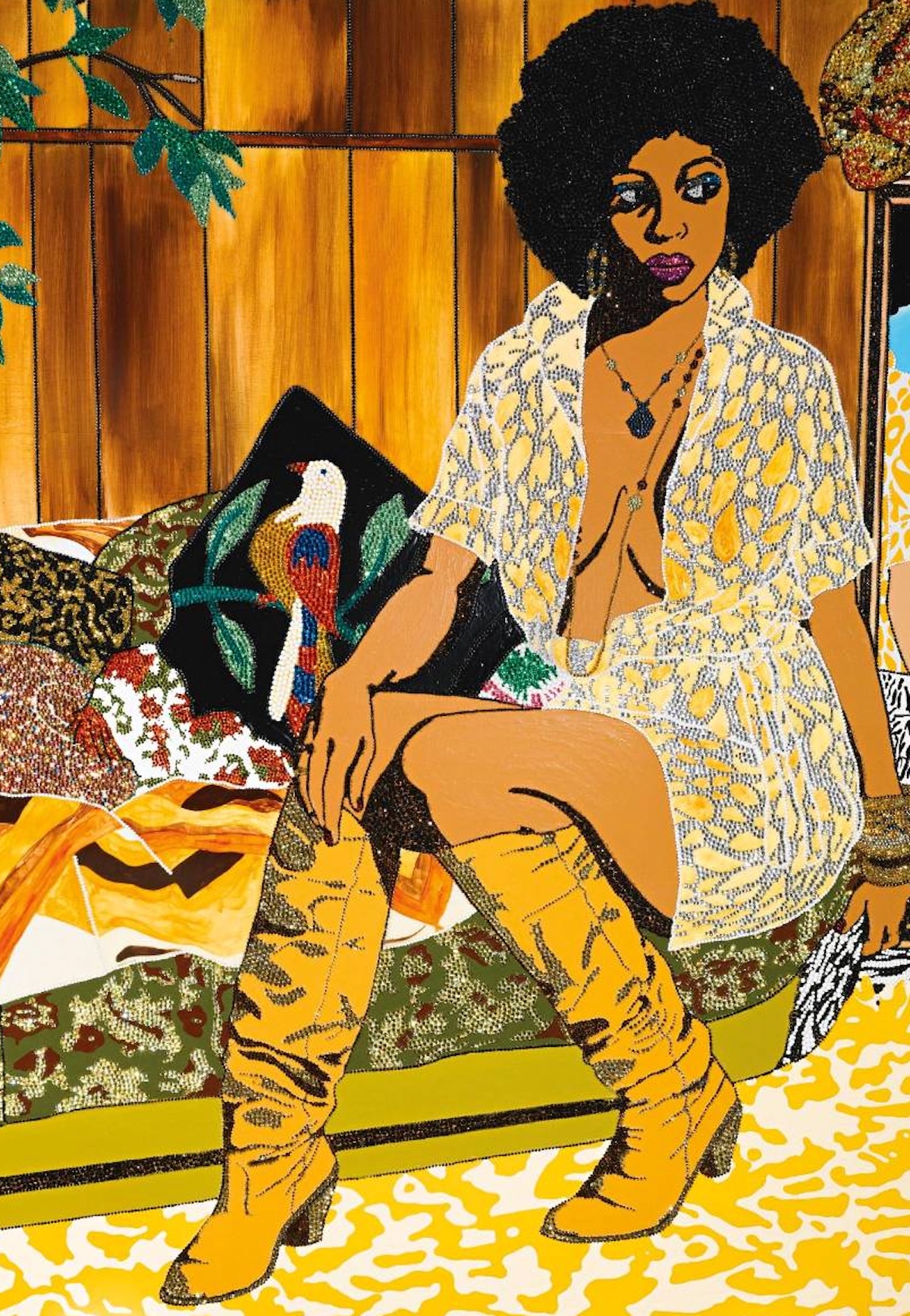

Thomas is often introduced as a painter, but to describe her only that way is to miss how central photography and staging are to her process. Many of the paintings begin with photographs she constructs: models posed in interiors Thomas designs, surrounded by furniture, textiles, and décor that quote the visual language of 1970s Black style while also nodding to the formal strategies of European painting. The work is composed before it is painted, and the painting becomes a second-order performance: a translation, an escalation, a re-assertion.

This matters because it complicates the easy narrative of “painting from life” and puts her closer to a lineage of artists who understand representation as produced rather than simply captured. The subject is not discovered; she is built, collaborated with, directed—like cinema, like fashion, like portrait studios. The staging is not an attempt to fake authenticity. It is an admission that authenticity is always mediated, and a decision to control the mediation rather than pretend it isn’t there.

That decision also reframes what “realism” means. Thomas’s work can feel hyper-real in its specificity—wood paneling, shag textures, mirrored surfaces—but it is also knowingly artificial. The artificiality becomes the point. If traditional portraiture has often used the trappings of wealth or taste to confer legitimacy, Thomas uses domestic glamour to confer something else: interior sovereignty.

The staging also allows her to revise power dynamics. In the history of Western painting, the Black woman’s body is frequently either absent or instrumentalized—exoticized, eroticized, positioned as accessory. Thomas flips the structure. Her subjects occupy the central seat. They meet the viewer’s gaze or ignore it with practiced authority. They do not appear to be waiting to be interpreted. They appear to be aware of interpretation and unimpressed by it.

Glitter, rhinestones, and the seriousness of adornment

The rhinestones have been treated, in some mainstream criticism, as the hook—an easy shorthand for her brand. But in the logic of her work, adornment is not decoration; it is language. A rhinestone surface can do several things at once. It can evoke the Black vernacular tradition of presentation—what it means to “step out,” to be seen, to look good as an act of dignity. It can quote the aesthetics of nightlife and performance, spaces where Black women have historically produced glamour without institutional permission. And it can function as an art-historical intervention: taking the “low” materials of craft, costume, and domestic ornament and using them to remake “high” portraiture.

There is also a practical effect: rhinestones disrupt the museum’s preferred viewing mode. Museums want viewers to behave, to keep distance, to look quietly. Thomas’s surfaces flirt with the opposite: they sparkle, they seduce, they pull your eye into constant motion. The work makes a case for pleasure as a legitimate form of knowledge—and, by extension, for Black pleasure as politically meaningful.

This is where Thomas’s practice can be read as both aesthetic and ideological. She is not merely representing Black women beautifully. She is asking why Black women’s beauty has so often been treated as suspect—either too much, too loud, too sexual, too “extra”—and she is building images that refuse to apologize for excess.

The mother as muse, the muse as person

It is impossible to understand Thomas’s emotional register without acknowledging the role of her mother not only as inspiration but as subject, collaborator, and narrative force. Thomas’s film Happy Birthday to a Beautiful Woman is one of the clearest windows into that relationship: a portrait of Sandra Bush that is affectionate without being sentimental, candid without being cruel. Accounts of the film describe Bush’s struggles—including health complications and addiction—and the complicated process of mother-daughter reconciliation.

This matters because Thomas’s portraits can look, to an untrained eye, like pure celebration—icons on couches, queens in patterned rooms. The film reveals the cost behind the iconography. The glamour is not escapism; it is a kind of reparative gesture. A mother whose life contained disappointment and pain becomes, in the daughter’s work, monumental. Not idealized into a fantasy, but elevated into visibility.

The artist’s willingness to let that visibility carry contradiction is part of her seriousness. Thomas does not treat her mother as a symbol. She treats her as a person whose life is shaped by structural forces—gender, race, class, health—and by personal choices that cannot be reduced to moral lessons. The result is a body of work that understands love not as a soft word but as an active labor.

“All About Love” as a thesis: Intimacy is political

The title “All About Love” is borrowed from All About Love: New Visions, and in the context of Thomas’s work, the phrase operates as both invitation and challenge: what happens if love is treated as a framework for politics rather than a retreat from politics? Coverage of the touring show emphasizes that Thomas frames love—familial, romantic, communal, self-directed—as a force with cultural consequences.

The touring itinerary itself has functioned like a cultural statement. Co-organized with The Broad and traveling to Barnes Foundation and Hayward Gallery, the exhibition has placed Thomas’s work in institutions with very different histories and audiences—testing how the work reads in Los Angeles versus Philadelphia versus London, and, later, in major European contexts where American racial iconography can be consumed as spectacle if not grounded in context.

Reviews have noted the show’s immersive quality—rooms that feel like living rooms, installations that incorporate music, books, and personal objects—suggesting Thomas is not satisfied with hanging pictures on walls. She wants to build an environment that honors the way Black life is lived: not in isolated images, but in rooms, in playlists, in textures, in the accumulation of memory.

In 2025, Le Monde described the exhibition’s “combattant” quality—its fighting spirit—connecting Thomas’s collage aesthetics and art-historical references to a broader tradition of militant African American art-making. The language is useful because it pushes back against the temptation to treat her work as merely decorative. Thomas is not only styling the world; she is arguing with it.

The museum, the canon, and the question of who gets to be central

Thomas’s work is frequently discussed alongside artists who have used figuration to rewrite the story of Black presence in art history. But her specific contribution is to treat Black women’s interiority as the central problem—and to insist that the solution is not simply “more images,” but better images: images that understand the politics of pose, the politics of gaze, the politics of domestic space.

This is why Thomas’s constant dialogue with art history matters. She has cited influences that range from European painting traditions to Black modernism and popular culture, and critics have noted how her work both quotes and disrupts canonical compositions. To quote a composition is not necessarily to endorse it; sometimes it is to reveal its exclusions. When Thomas “reimagines” the canon, she is exposing the canon’s assumptions—about who can be Venus, who can be odalisque, who can be muse, who can be protagonist.

Her subjects also complicate the museum’s appetite for a single story of Black womanhood. They are not presented as universal representatives. They are specific: different bodies, different moods, different relationships to the viewer. Some appear confrontational; others appear serenely self-contained. Some are explicitly sensual. Some are posed in ways that reference fashion photography, emphasizing how Black women have often had to navigate being looked at as a condition of being in public life.

Thomas’s work refuses to moralize that navigation. It insists that desire exists, that pleasure exists, and that those facts are not shameful. The insistence is especially charged in a cultural context where Black women’s sexuality has been historically policed—either hyper-visible in exploitative ways or erased in “respectable” narratives.

Fame, fashion, and the porous boundary between art and culture

Thomas’s practice has never pretended that the museum is the only place images circulate. She has worked with fashion and editorial culture, and public conversations hosted by The Washington Post have highlighted her collaborations and her views on the power of art beyond gallery walls.

This porousness is not a side hustle. It is consistent with the internal logic of her work, which already blends the codes of “high art” and “popular” imagery. Thomas is attentive to how Black women appear in magazines, in music, in celebrity portraiture, and how those appearances shape what audiences consider normal or aspirational. The visual language of her paintings—bold patterns, styled rooms, cinematic lighting—often echoes the language of editorial shoots precisely because editorial shoots have been one of the arenas where Black representation has been contested.

Her engagement with fashion has also made visible a central tension in her career: the art world’s appetite for Black aesthetics, and the risk that institutions will celebrate the “look” while ignoring the critique embedded in it. Thomas’s work is frequently praised for being vibrant and empowering, but empowerment can become a marketing term if it is not tethered to the structural questions the work raises.

The Harris portrait episode and the politics of commission

One of the most revealing public episodes in recent coverage of Thomas’s career involves a commission that did not come to fruition: a reported effort connected to a portrait of Kamala Harris. In a conversation reported by The Washington Post’s Robin Givhan, Thomas discussed the constraints of working under commission and the reality that even celebrated artists can face institutional friction when the subject is both political and symbolic.

The significance of that episode is not gossip; it is structural. Portraiture has always been tied to power. Who gets commissioned, under what conditions, and with how much artistic freedom are questions that reveal what institutions actually value. If Thomas’s work is partly about Black women controlling their image, then any high-profile commission becomes a test: will the institution allow that control, or will it demand a safer, flatter picture?

Even without treating the specifics as definitive (public reporting is necessarily partial), the episode underscores something Thomas’s career already demonstrates: visibility is negotiated, often contentiously, and artists who challenge the visual status quo can be celebrated in the abstract while constrained in practice.

A Brooklyn Museum milestone and the language of institutional validation

Institutional recognition has been a major part of Thomas’s trajectory, and in 2012 the Brooklyn Museum mounted “Origin of the Universe,” an exhibition that introduced many museum audiences to the scale and ambition of her portraits.

The title itself is telling: a cosmic claim for a body of work deeply invested in the everyday—couches, carpets, mirrors, living rooms. Thomas’s move is to treat those domestic details as worthy of grandeur, to suggest that Black women’s interior spaces contain universes of history and desire.

“Origin of the Universe” also arrived at a moment when American museums were beginning—slowly, unevenly—to face their representational failures. Thomas’s work, in that context, can read as both a beneficiary of institutional change and a driver of it. Museums did not simply “discover” her. Her work forced a conversation about why it had taken so long for such images to be taken seriously within mainstream institutions.

The aesthetic of collage as an ethic of complexity

Thomas’s practice is often described as mixed media, and that phrase can sound like a technical footnote, but in her case it is closer to an ethic. Collage is a way of thinking: assembling fragments, acknowledging discontinuity, refusing a single seamless narrative. As Le Monde noted in its discussion of “All About Love,” collage functions as both method and mindset—an intellectual invitation to read the work as layered rather than singular.

This is particularly resonant for an artist whose subject is Black womanhood, which in American culture has often been forced into simplified scripts: the strong Black woman, the hypersexualized figure, the caretaker, the victim, the icon. Collage allows Thomas to resist those scripts formally. The image becomes a site where contradictions can coexist.

Even the decorative patterns—so easy to dismiss as merely “stylish”—function as collage. They are quotations from a visual archive: textiles, wallpapers, magazine layouts, the aesthetic codes of a particular era of Black style and aspiration. By putting those codes on the same plane as art-historical references, Thomas collapses the hierarchy that says one set of images is “serious” and the other is “mere culture.”

Queer visibility without the tourist gaze

Thomas’s work also matters because it brings Black queer desire into the frame without turning it into spectacle. In interviews around “All About Love,” she has spoken about love as a political force and about representing intimacy as something more than provocation.

The history here is heavy. Western art is full of erotic imagery, but Black bodies within that imagery have often been treated as either taboo or fetish. Thomas’s images, by contrast, insist on agency. They do not ask permission to depict desire, and they do not present desire as a problem to be solved. They present it as part of a full life.

This is where the work can feel quietly radical. It does not perform “respectability” to earn museum entry. It does not soften itself into palatability. It makes a case that Black queer life is not marginal; it is central, textured, ordinary, and—crucially—worthy of beauty.

A global stage and the question of translation

As Thomas’s work circulates internationally, a new set of questions emerges: how does an American visual argument about Black womanhood translate in places where racial politics operate differently? A late-2025 feature about a major presentation at Grand Palais described the exhibition’s immersive approach and its scale, emphasizing the way Thomas builds domestic vignettes with music and personal artifacts to shape how viewers enter the work.

International acclaim can be double-edged. On one hand, it signals that Thomas’s formal intelligence—her command of composition, her material inventiveness, her ability to build environments—reads as significant beyond a U.S. context. On the other hand, the global art world can consume Black American aesthetics as trend, extracting style while ignoring the politics that generated it. Thomas’s insistence on context—on rooms, on objects, on love as framework—can be understood as a defense against that flattening. She is not offering images as exportable products; she is offering worlds.

Accomplishment as infrastructure, not just accolades

If you try to measure Thomas’s significance only through typical art-world metrics—exhibitions, sales, institutional collections—you will capture part of the story and miss the deeper one. Her accomplishment is not simply that she has been celebrated. It is that she has expanded the visual vocabulary available to Black women in contemporary art.

She has made it harder for museums to pretend that Black women’s portraiture is niche. She has made it harder for critics to dismiss adornment as unserious. She has made it harder for viewers to treat domestic Black life as merely background. And she has helped normalize the idea that Black queer intimacy belongs on museum walls without apology.

This is influence as infrastructure: changing what becomes possible for other artists, changing what audiences expect to see, changing what institutions can plausibly claim they cannot accommodate.

Even commentary outside traditional art criticism has registered that influence. A 2024 “most influential” feature by The Root pointed to the cultural impact of “All About Love” and framed Thomas’s work as legacy-making—art that centers Black womanhood with audacity and historical awareness.

What the work asks of the viewer

There is a temptation, especially among sympathetic audiences, to approach Thomas’s work as affirmation alone—images that make you feel good, that correct injustice by offering beauty. That reading is not wrong, but it is incomplete. Thomas’s work is not only affirmation. It is confrontation, though often delivered with pleasure.

The paintings ask: why is this image surprising to you? Why does it feel “new” to see Black women posed with the authority that European portraiture has long granted white subjects? Why does glamour read as political here? What histories of exclusion make these questions necessary?

Her installations ask something else: what would it mean for museums to feel like spaces where Black life is not merely displayed but understood? What would it mean for cultural institutions to honor the textures of everyday life as worthy of aesthetic seriousness?

And perhaps most pointedly, the work asks: what happens when Black women are not only seen, but allowed to control how they are seen?

The journalistic caution: The myth of the single narrative

Any longform account of a living artist risks turning a career into a clean arc—struggle, breakthrough, triumph. Real lives are messier. Thomas’s story contains triumph, but it also contains the ongoing negotiations that any Black woman artist faces in a market that can be both hungry and limiting: hungry for Blackness as style, limiting in what it expects Blackness to mean.

What makes Thomas compelling is that she has refused, again and again, to let her work be reduced to a single function. It is not only “representation.” It is not only “critique.” It is not only “celebration.” It is all of these at once, layered like the surfaces she builds.

The rhinestones, in the end, may be the best metaphor for her project. Each one is small. One alone could be dismissed as ornament. But assembled—hundreds, thousands—they form a surface that changes how light behaves. Thomas has done something similar with the archive of images available to Black women. She has taken what was treated as minor—domestic style, adornment, sensuality, staged glamour—and assembled it into a visual field that commands attention. Not because it begs for it, but because it has decided it is owed.

That decision—formal, political, intimate—is why her work lasts beyond the first glance. It makes looking feel like responsibility.