He is invoked not only as inspiration but as evidence. Evidence that the barriers were never about capacity

He is invoked not only as inspiration but as evidence. Evidence that the barriers were never about capacity

By KOLUMN Magazine

The mythology of American business loves a certain kind of origin story: a lone genius with a garage, a lucky break, a clean ascent. Reginald F. Lewis offers a different template—less fairy tale than blueprint. His life sits at the tense intersection of race and capital in the late twentieth century, when the United States was loudly celebrating deregulation, “innovation” in finance, and the swagger of the takeover boom, while quietly keeping the most lucrative corridors of power gated by relationships that rarely included Black men. Lewis did not simply become wealthy in that world; he learned its internal logic, spoke its language, and—most importantly—proved that a Black owner could operate at a scale most Americans were trained not to imagine. His signature achievement, the $985 million purchase of Beatrice International Foods from Beatrice Companies, was widely described as a landmark offshore leveraged buyout, a deal so large that the numbers alone could cause the story to blur into abstraction. But Lewis’s significance isn’t just in the size of what he bought. It’s in what he made visible—how power is assembled, how credibility is manufactured, and how representation at the top of the economy is not a matter of symbolism but of structure.

He came of age in a nation that promised “equal opportunity” in the language of civics and denied it in the practical mechanics of finance. Lewis responded not with resignation, but with strategy: education, legal fluency, deal craft, and an insistence on moving from the margins into the rooms where decisions were made. He became, in effect, a translator between worlds—bringing the ambitions of Black America into boardrooms that had long treated those ambitions as either irrelevant or inconvenient. His story is a narrative about money, yes, but also about the politics of access: who gets banked, who gets vouched for, whose mistakes are tolerated, whose successes are presumed to be anomalies.

Lewis also demonstrates a harder truth about American meritocracy: talent is necessary, but rarely sufficient. The gatekeepers of capital tend to trust what looks familiar. Lewis, as a Black man pursuing big-ticket acquisitions in the 1980s, did not look familiar to the institutions he needed. So he built familiarity through performance—overprepared, over-informed, relentlessly composed. Friends, colleagues, and later chroniclers have described a man who could be both charming and surgical, who understood that the appearance of inevitability can be as important as the underlying economics. When people told him “no,” he treated it less as a verdict than as data—information about what he needed to change in the pitch, the structure, or the cast of participants.

That approach—part legal mind, part financier’s nerve—made him an emblem in Black business history. But his legacy is more complicated than the legend. The takeover era rewarded leverage, cost-cutting, and the reengineering of companies into financial instruments. Lewis operated inside that system, using its tools. Any serious account of his life has to acknowledge both the ingenuity required to navigate that world and the ethical scrutiny that hangs over the era itself: what happens to workers, communities, and long-term innovation when corporate ownership is guided primarily by debt service and investor returns? Lewis’s life invites that question without reducing him to it. He was a product of the system—and also, in key ways, a challenger to its racial hierarchies.

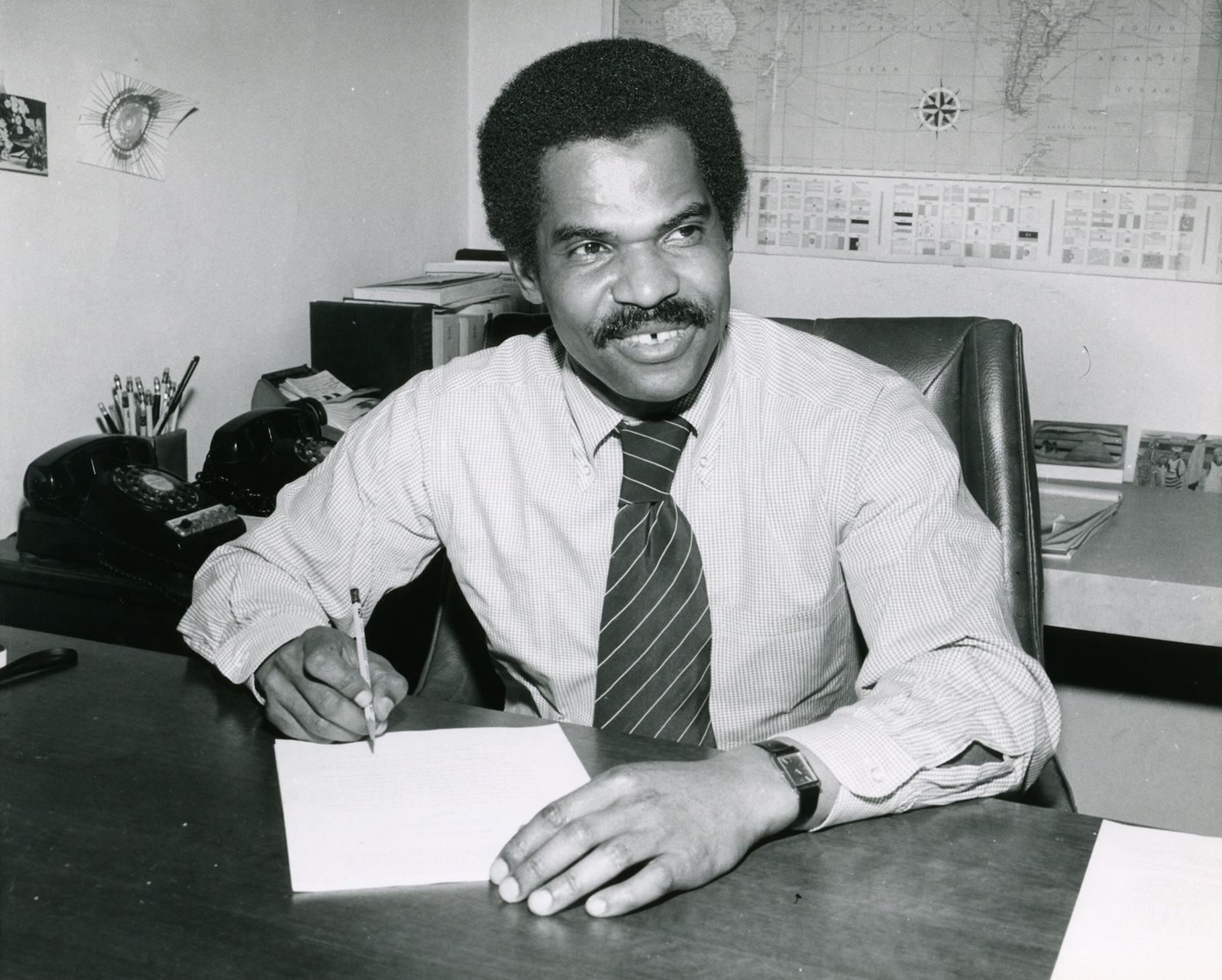

East Baltimore, the discipline of ambition, and a lesson from a paper route

Lewis was born in Baltimore in 1942, in a segregated city whose neighborhoods were shaped by policies that determined who could live where, who could borrow, and whose businesses could grow. He grew up in a Black community where achievement was both encouraged and constrained: parents and teachers often pushed children toward excellence as a form of protection, even when society offered no guarantee that excellence would be rewarded fairly. Lewis internalized that lesson early, and the stories that endure about his childhood tend to emphasize enterprise as habit. One of the most repeated: as a boy, he built a newspaper route delivering the Baltimore Afro-American, expanding it well beyond its original footprint and eventually selling it for a profit. In the telling, it’s a neat parable: a kid learns market-building, customer relationships, and the value of an asset—even a modest one. But the deeper point is about imagination. A paper route becomes a business when you decide it is.

Schooling was part of that discipline. Lewis attended Virginia State University on a football scholarship, a pathway familiar in Black communities: athletics as a bridge into higher education, and higher education as the bridge beyond the limits of local opportunity. He was not raised inside generational wealth; his advantage was not access but appetite. At Virginia State, he encountered a tradition of Black institutional life that treated leadership as duty, and excellence as collective uplift. That ethos mattered later, when he began giving away money at levels that signaled not just generosity but institutional seriousness.

After college, he made a leap that, for a Black man of his era, was both formidable and consequential: Harvard Law School. Harvard offered him pedigree, but also exposure to the machinery of American corporate power. Law school taught him something beyond doctrine: how elite networks form, how arguments are packaged, how to anticipate the objections of people who assume they’re the smartest in the room. Lewis used that training less as social polish than as armor.

The details of his early legal career are often summarized in short lines—prestigious firms, corporate law, ambition. Yet the significance lies in what those early years represented. Corporate law, especially in New York, sits close to capital. It is where deals are structured, risks allocated, and language crafted to protect the interests of money. Lewis learned, from the inside, how companies are bought and sold—how an acquisition is not merely an act of purchase but an engineering project. That is the core skill of modern finance: to create structures that make the improbable bankable.

The lawyer who wanted to be the buyer

Lewis’s pivot from lawyer to dealmaker is the hinge of his life. It is one thing to advise clients on transactions; it is another to become the client—particularly when the client is a Black man asking bankers to lend him sums that would place him among the biggest players in American business. By the early 1980s, Lewis began building the vehicle that would allow him to make that leap: TLC Group, the firm through which he pursued acquisitions.

His early deals were not instantly iconic, but they were strategically chosen. The story of the McCall Pattern Company purchase is a case study in how Lewis thought. He identified an asset that looked unfashionable to the mainstream—sewing patterns, a business tied to a domestic culture that seemed to be fading—and found value where others saw decline. He negotiated hard on price, assembled financing, and then worked the operational levers that turn an acquisition into a success: freeing trapped capital, improving efficiency, recruiting talent, and repositioning the business. The point wasn’t simply to make money. It was to build a track record—proof to lenders and investors that he could buy, manage, and exit with returns.

That “proof” mattered because Black entrepreneurs have long faced an extra burden in capital markets: the need to perform credibility, repeatedly, in a system that often treats them as exceptions rather than peers. Lewis understood that the challenge wasn’t only raising money. It was raising confidence. Deal by deal, he accumulated both.

Still, the leap from a mid-sized acquisition to a near-billion-dollar global buyout is a canyon. To cross it, Lewis needed not only a compelling target but also an era in which the financial system was willing to finance audacity. The 1980s were that era. The rise of leveraged buyouts—transactions funded largely by debt—created a new class of corporate actor: the buyer who didn’t need to be a traditional industrialist, as long as he could assemble capital, manage lenders, and promise returns. Lewis, a corporate lawyer turned entrepreneur, was built for that environment.

But the same era also produced skepticism: about the social value of these deals, about the human costs, about the way debt could transform companies into vehicles for repayment rather than long-term growth. Lewis’s story lives inside that complexity. He wasn’t the only buyer using leverage. He was one of the few Black buyers with access to the table at all.

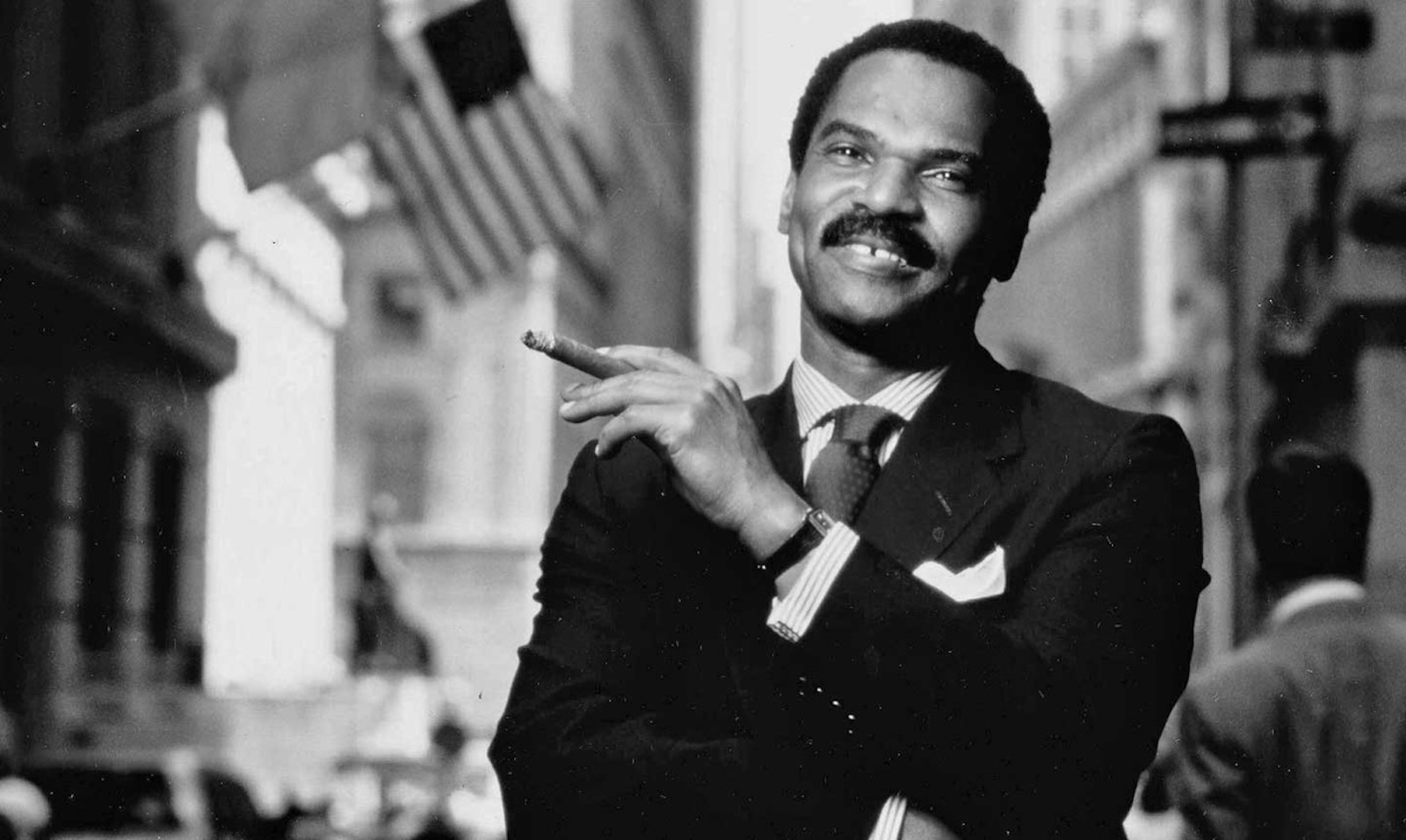

The Beatrice buyout: Scale as a statement

In 1987, Lewis executed the transaction that would secure his place in business history: the purchase of Beatrice International Foods for $985 million. Contemporary reporting framed it as a feat of financial engineering—an enormous offshore leveraged buyout involving dozens of subsidiaries and operations across many countries. Lewis renamed the acquired business TLC Beatrice International Holdings, and for a time it was described as the largest Black-owned business in the United States.

The mechanics of such a deal are intricate, but the broad outline is clear: Lewis had to persuade sellers that he could close, persuade lenders that the debt would be serviced, and persuade the market that his ownership would not be a symbolic experiment but a competent regime. Reporting from the period highlighted how big the acquired enterprise was—numerous subsidiaries, tens of thousands of employees, operations spanning multiple continents. He also operated within the financing ecosystem of the era, which included high-profile Wall Street players and the aggressive debt markets that made mega-deals possible.

In Black business circles, the deal reverberated as more than a transaction. Black Enterprise later described it as groundbreaking, noting its role in creating a Black-owned conglomerate surpassing $1 billion in annual revenues and inspiring generations of Black dealmakers. That inspiration wasn’t abstract. It was occupational: Lewis’s success offered proof of concept for Black professionals who wanted to work in investment banking, private equity, corporate law, and executive leadership—and who needed examples of Black ownership at the highest levels to imagine such careers as plausible.

The deal also had a symbolic dimension that should not be underestimated. In American life, “firsts” function as both celebration and indictment. A first is evidence of progress; it is also evidence of how long exclusion has endured. Lewis’s acquisition forced a question that had long been answered quietly by the absence of Black owners at scale: if a Black entrepreneur can build and buy at this level, why has the system produced so few? His life makes it difficult to attribute the gap to ability. It directs attention back to access.

Leadership, pressure, and the choreography of credibility

After the headlines, there is the work of running a sprawling conglomerate. The public often remembers Lewis in the posture of dealmaker—decisive, impeccably dressed, projecting certainty. Yet leadership at scale is less about posture than process: how you build teams, manage operations across geographies, balance debt obligations with investment needs, and handle the perpetual scrutiny that follows a historic “first.”

Lewis faced an additional layer of pressure: he was never just running a company. In the public imagination, he was representing a possibility. That is a heavy, often unfair burden placed on pioneering figures. When they win, their success is treated as extraordinary. When they stumble, their failure is generalized. Lewis understood this dynamic. It shaped how he presented himself, how he spoke about business, and how he navigated elite spaces. He cultivated relationships not simply as social climbing but as institutional leverage: access to capital, access to expertise, access to deal flow.

Those who study his era also note that his model of ambition was unapologetically capitalist. He wanted size, influence, and permanence. That matters because Black political discourse has often been split between integrationist visions—gaining access to existing systems—and liberationist visions—building alternatives. Lewis leaned toward the former, though he carried the latter’s moral urgency. He sought to win inside the system, then redirect some of its benefits outward through philanthropy and institutional support.

Philanthropy as infrastructure, not image

Lewis’s giving is sometimes summarized as a coda: the rich man donates, institutions are grateful, legacy secured. In his case, philanthropy looks less like reputation management and more like strategy. He established The Reginald F. Lewis Foundation in 1987, the same year as the landmark acquisition—an alignment that suggests he understood wealth and institutional giving as parallel forms of power.

His major gifts were consequential in both size and symbolism. The foundation made a notable unsolicited gift to Howard University, reported as $1 million, which was matched by the federal government, supporting scholarships and academic initiatives. In 1992, he donated $3 million to Harvard Law School—then described as the school’s largest individual gift—and the institution renamed its International Law Center in his honor. That naming mattered. Elite universities are museums of prestige; what they choose to name after whom is part of how they narrate belonging. A major facility bearing the name of a Black businessman signaled a shift in who could be remembered as central to the institution’s story.

Lewis also carried a desire that extended beyond universities: support for African American history and cultural memory. After his death, the foundation helped underwrite a major museum project in Baltimore. The Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture opened with support that included a $5 million grant from the foundation, according to reporting and museum documentation. The museum’s existence reframes his legacy. Lewis is not only remembered through balance sheets, but through public history—through an institution dedicated to narrating Black life across centuries. In a nation where Black history has often been treated as a footnote, underwriting a museum is a political act: it funds not just exhibits, but the authority to tell the story.

There is also a philosophical coherence to these gifts. Lewis’s own ascent depended on institutions—schools, professional networks, capital markets—that historically excluded Black people. His philanthropy, in turn, strengthened institutions that expand Black access: HBCUs, scholarships, cultural memory. In that sense, he treated money not merely as personal reward but as a tool for building durable civic capacity.

Death at 50, and the question of unfinished time

Lewis’s life ended abruptly in January 1993. He was 50. Contemporary obituaries described his death as a cerebral hemorrhage connected to brain cancer. The fact pattern is stark: a man who had forced open a door at the highest end of American capitalism did not live long enough to shape the long-term arc of what he built in the way older industrialists often do. Death froze him in a particular cultural posture—perpetually in ascent, permanently “promising,” always slightly ahead of the next generation that would follow.

The reporting around his death emphasized both his business stature and his symbolic status. The Washington Post described him as chairman of TLC Beatrice International Holdings and highlighted the circumstances of his passing. Los Angeles Times similarly underscored his role in building the nation’s largest Black-owned business and noted the illness that preceded his death. His death, coming at the edge of midlife, sharpened the sense that his project was unfinished—not only the company’s trajectory, but the broader cultural task of normalizing Black ownership at scale.

In the years after, corporate histories and biographies have debated how to measure his impact. Some accounts track the later evolution of the company and its ownership transitions. Others focus less on the firm’s eventual fate and more on Lewis’s methodological contribution: he showed, with evidence, that Black ambition could translate into global corporate control. That proof does not disappear even when the specific corporate entity changes hands. The lesson outlives the asset.

The meaning of “first” in an unequal economy

It is tempting to treat Lewis as a heroic exception, an outlier whose brilliance explains his success. That reading is flattering, and incomplete. The more instructive interpretation is structural: Lewis succeeded by mastering systems that were not designed for him, and by finding ways—through legal expertise, disciplined deal-making, and relentless persuasion—to borrow credibility until his results produced their own. His story reveals how much of business is not simply innovation, but gatekeeping. It reveals how markets are shaped not just by supply and demand, but by trust—and how trust is distributed along lines of race, network, and historical familiarity.

That is why Lewis still matters. In contemporary conversations about racial wealth gaps, access to venture capital, and the scarcity of Black-owned firms at massive scale, his life provides a reference point. It rebuts the lazy claim that the issue is a lack of ambition. The ambition was there. The question has always been: who is financed, and why?

His life also complicates easy narratives about Black success. Lewis did not escape capitalism; he excelled at it. He used leverage, negotiated hard, and played in markets that often reward ruthlessness. Yet he also insisted on Black presence in places that had treated it as unwelcome, and he directed meaningful resources into Black institutions. He was, in a sense, bilingual: fluent in Wall Street’s logic, and still tethered to the moral language of community responsibility.

This bilingualism may be his most enduring lesson for today’s entrepreneurs and civic leaders. Representation at the top is not just a matter of visibility. It changes what gets funded, which institutions endure, and how history is preserved. Lewis understood that, even if he did not have time to complete everything he might have built.

A legacy you can walk into

In Baltimore, you can walk into the museum that carries his name and feel the argument made concrete: that wealth can be converted into public memory, that private success can underwrite collective narrative. In Cambridge, you can see his name attached to a major law center at Harvard, embedded into the architecture of elite education. In business journalism and Black corporate lore, you can trace how his deal became a shorthand for possibility—the moment when “Black-owned” and “billion-dollar” could be said in the same breath without irony.

But perhaps the clearest measure of Lewis’s significance is how often his story resurfaces when the country debates race and opportunity. He is invoked not only as inspiration but as evidence. Evidence that the barriers were never about capacity. Evidence that access is curated. Evidence that when a Black entrepreneur gets the capital, the counsel, and the latitude to operate at full scale, the results can be historic.

In that sense, Reginald F. Lewis is not only a figure from the 1980s takeover era. He is a continuing challenge to the present: if one man could do this then, what is our excuse now?