The United States repeatedly demonstrated that Black excellence did not disarm racism; it often provoked it

The United States repeatedly demonstrated that Black excellence did not disarm racism; it often provoked it

By KOLUMN Magazine

The making of a “schoolman” in a city built on slavery

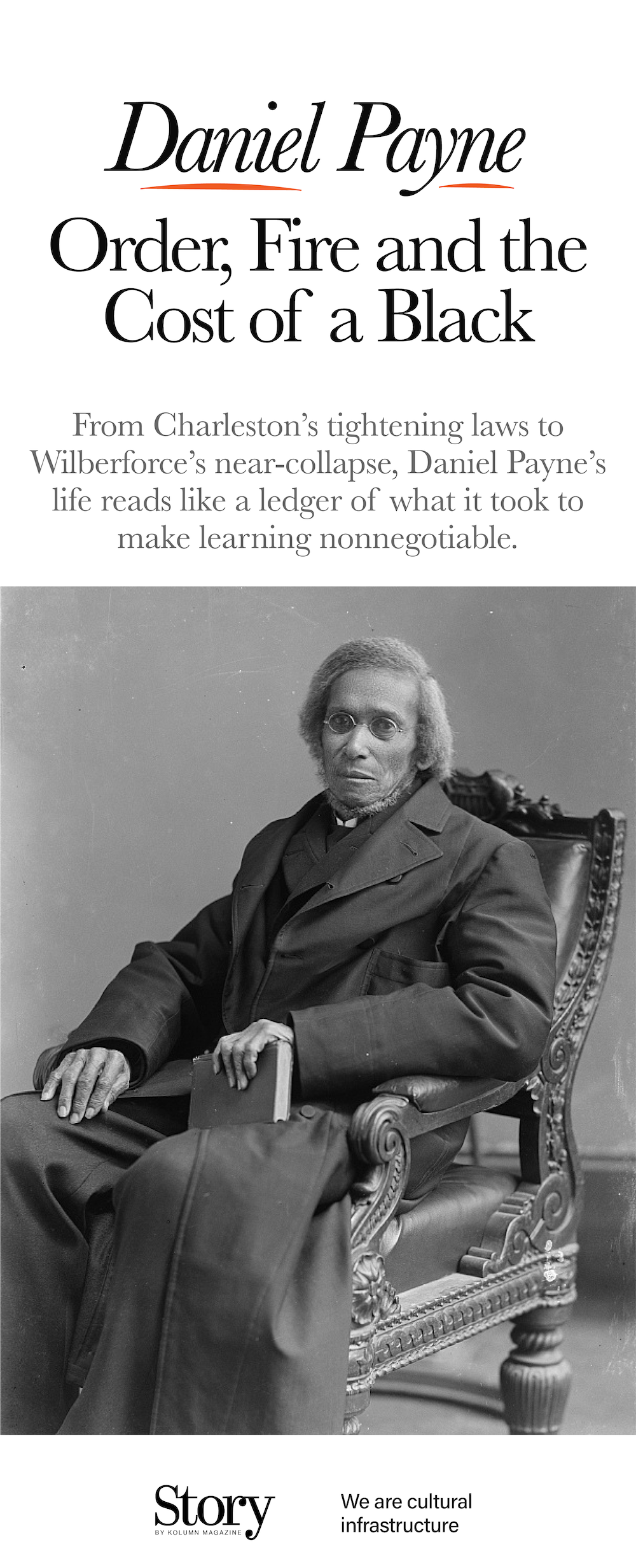

In the early nineteenth century, Charleston offered a brutal paradox: a dazzling port city whose wealth was inseparable from human bondage, and a place where a small but significant community of free Black people tried to carve out futures under laws designed to prevent exactly that. Daniel Payne—born Daniel Alexander Payne in 1811—came of age inside that contradiction. He was free, but freedom in Charleston was a revocable condition, continually re-policed by statute, custom, and suspicion.

Payne’s later reputation would be made in pulpits, on episcopal tours, and in the boardrooms of Black institutions. But his first vocation was education in the most literal sense: opening schools, teaching children and adults, and treating literacy as a spiritual discipline rather than a mere skill. In his late teens, he began teaching in Charleston, building a small school that became the kind of quiet threat slave societies learn to fear—an ordinary room where Black people learn to read.

The fear became policy in the wake of Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion. Across the South, lawmakers tightened restrictions on Black mobility and Black learning, often collapsing the distinction between enslaved and free in the name of social control. South Carolina’s clampdown made the act of teaching Black people newly perilous and, in many cases, explicitly illegal. Payne’s school closed under that pressure, and the closure was not simply an interruption; it was a lesson in how fragile Black progress could be when it relied on the tolerance of a regime built to deny Black humanity.

What Payne did next mattered for the rest of his life: he left. He traveled north in search of formal education—both because he hungered for it and because he understood, early, that credentialing could function as a kind of armor. He studied at Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg, a decision that placed him in a religious tradition not typically centered in Black nineteenth-century narratives, and that exposed him to the power and limits of predominantly white ecclesial institutions.

By the late 1830s, Payne was ordained a Lutheran minister—an extraordinary milestone in a country that still argued, in courts and newspapers and churches, about whether Black people were fit for full citizenship, full humanity, full participation in anything. The fact of ordination did not dissolve white supremacy, but it did give Payne a platform, and it sharpened his sense that ministry without learning could become manipulation, even when it was sincere.

Yet his Lutheran period also revealed something that would haunt much of Black leadership in the nineteenth century: the tension between individual accomplishment and institutional belonging. Payne could be educated, even ordained, and still be constrained by the racial boundaries of American religious life. He would ultimately find his most consequential home in the Black-led denomination that had already declared, by its very existence, that Black Christians were not obliged to beg for spiritual authority.

That denomination was the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Choosing a Black church, and redefining what it could demand

If Payne’s early years were shaped by the violence of anti-literacy laws, his adult life was shaped by a different kind of argument: what should a Black church be, beyond a refuge? For many Black Americans, the church was the central institution—sometimes the only durable one—capable of producing leadership, mutual aid, public voice, and a sense of peoplehood. But the church also carried competing impulses. There was the ecstatic, improvisational spiritual tradition that held enslaved communities together. There was the “respectability” tradition, shaped in part by the politics of survival in a white supremacist society, that leaned toward formality and discipline. And there was the ever-present demand that the Black church, unlike white churches, do more than one job at a time: worship, educate, fundraise, organize, shelter, advocate.

Payne came to believe that the Black church could not afford an anti-intellectual posture—not because he despised emotional worship, but because he saw ignorance as a vulnerability that slavery and racism would exploit. He joined the AME Church in the 1840s and soon began pushing for higher educational standards among ministers, insisting that preaching should be accountable to theology, history, grammar, and the broader life of the mind.

This was not a universally popular stance. In any tradition, raising standards can look like closing doors, and in a Black denomination that had grown under intense constraint, some saw formal requirements as an elitist project—education as a barrier rather than a bridge. Payne’s critics, then and later, would sometimes frame him as too enamored of order, too suspicious of “shout” worship, too eager to align Black religious life with European norms. But his supporters would argue that he was protecting Black communities from the consequences of being denied education—protecting them from predatory interpretations of scripture, from weak institutional governance, from leaders unprepared to negotiate with hostile power.

In 1848, the AME Church named Payne its historiographer. The appointment was telling: it signaled that the denomination understood memory as a battleground. In a nation where Black history was routinely erased or distorted, writing the church’s history was not clerical housekeeping; it was a claim to legitimacy, continuity, and intellectual authority. Payne would go on to publish significant historical and autobiographical work, including Recollections of Seventy Years, which offers a window into the interior life of a Black leader navigating the nineteenth century’s moral emergencies.

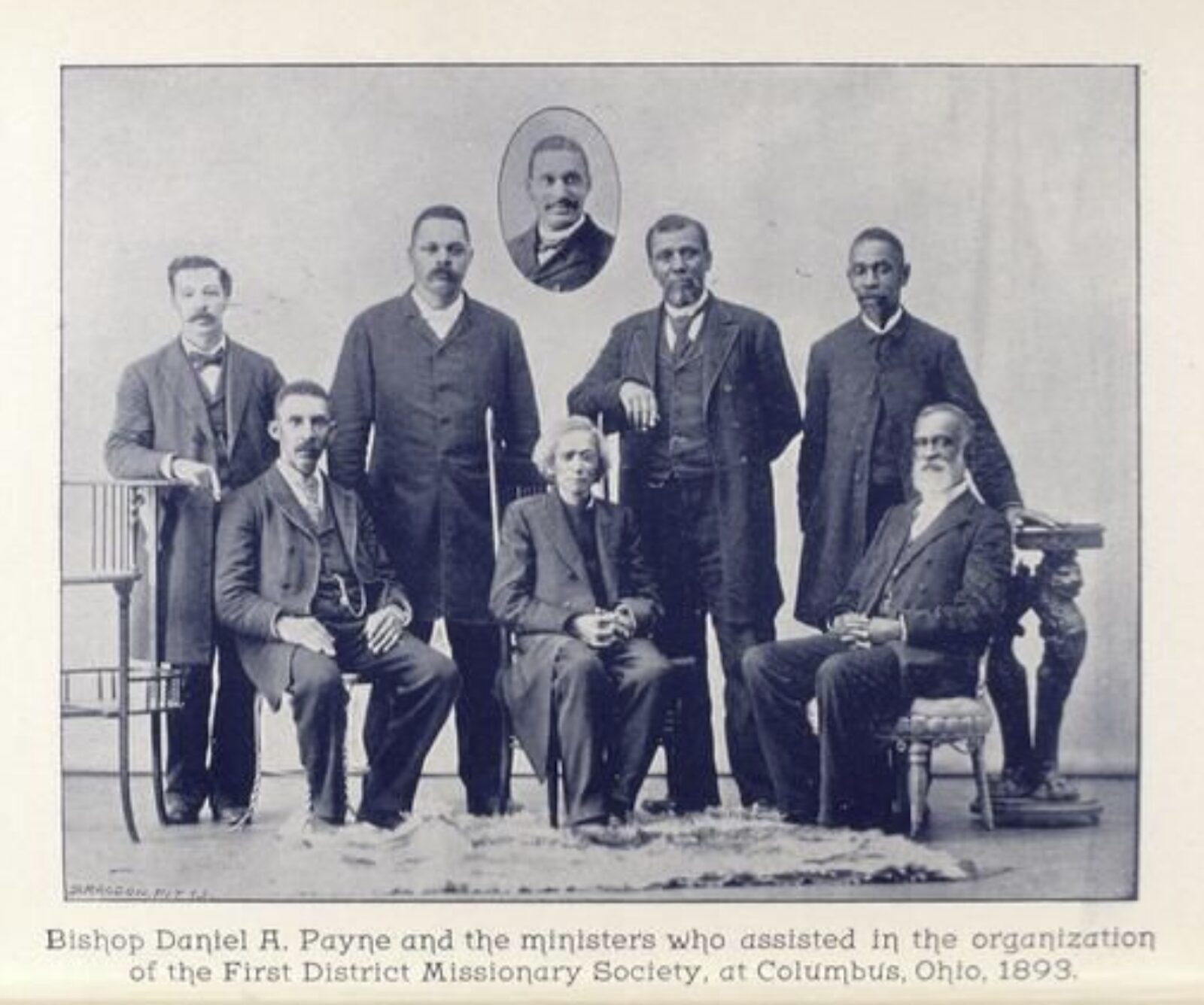

Four years after becoming historiographer, he rose higher still. In 1852, the AME Church elected him bishop—its sixth. The office did not simply confer status; it imposed a logistical reality. Bishops traveled constantly, overseeing conferences, adjudicating disputes, organizing congregations, and raising funds. Payne used that reach to press his educational agenda across the denomination, in effect treating the AME as a system capable of scaling Black learning.

He also carried the church into a wider world. A recent The Guardian piece on Harriet Tubman’s church in Canada notes that an AME church in Ontario was dedicated in 1855 by Daniel Payne—evidence of how Black religious networks crossed borders, following the routes of freedom seekers and the needs of new communities.

But Payne’s most consequential institutional bet would be made not in a sanctuary, but on a campus.

Wilberforce University and the idea of Black-controlled higher education

When Americans speak about Historically Black Colleges and Universities, they often do so in the language of nostalgia or celebration. Less often do they speak plainly about the structural audacity these institutions represented in their earliest years: an insistence that Black people were not only entitled to higher education, but capable of governing it, financing it, staffing it, and defending it against political and economic sabotage.

Wilberforce University—founded in Ohio in the 1850s—became one of the central stages on which Payne played out his belief that education was inseparable from freedom. He served on the founding board associated with the school’s creation in 1856, and when the institution later struggled and changed hands, the AME Church took a decisive step.

In 1863, amid the Civil War’s upheaval, the AME Church acquired Wilberforce and selected Payne to lead it. He became, as multiple accounts emphasize, the first African American president of a U.S. college. This “first” is more than trivia. It signals a shift in what Black leadership could be: not merely charismatic oratory or abolitionist agitation, but executive stewardship over an institution devoted to advanced learning.

The challenges were immediate and punishing. Running a college during wartime—especially a Black-led college—meant unstable funding, uncertain enrollment, and the constant threat that white philanthropy or white political support could evaporate without warning. Payne approached the work as both administrator and pastor. He raised money, recruited faculty, stabilized governance, and tried to build something durable enough to outlast the moment’s enthusiasm.

There is a temptation, in retrospect, to treat the purchase of Wilberforce as inevitable, as though the growth of Black higher education flowed naturally from emancipation. Payne’s story argues the opposite. Nothing was natural about it. Black schooling in America has typically been built in hostile weather: erected quickly, underfunded, overburdened, then criticized for the very deficits the society imposed. Payne’s genius was to treat that hostility as a reason to build stronger systems, not to lower ambitions.

He led Wilberforce for more than a decade, stepping away from the presidency in the 1870s. But the significance of his tenure is not only that he held the role; it’s that he helped make plausible the idea that Black people could own and operate institutions of higher learning—an idea that would become a lifeline in the decades when Reconstruction collapsed and Jim Crow hardened.

To understand what Payne was really doing at Wilberforce, it helps to treat him as both educator and strategist. He was training individuals, yes. But he was also building an institutional counterweight to a nation that used law, terror, and economics to keep Black people politically weak and intellectually starved.

Reconstruction: Building a church that could function like a state

Payne’s life spans a violent arc: born in the early republic, matured as abolitionist struggle intensified, served as bishop through the Civil War, and labored through Reconstruction’s promise and betrayal. After emancipation, millions of formerly enslaved people faced a question with no easy answer: what does freedom require, immediately, to become real?

The AME Church offered one answer: organization. Payne quickly organized missionary work among freed people in the South, helping expand the denomination dramatically in the Reconstruction period. The details differ across retellings, but the core point holds: the church became a vehicle for building community infrastructure where the state refused to do so reliably, and where white violence often targeted Black autonomy.

In practice, this meant ministers who could read contracts, negotiate with hostile local authorities, and teach. It meant churches that could host schools. It meant governance structures capable of holding together congregations dispersed across regions still simmering with Confederate resentment. Payne’s obsession with education and order—so easy to caricature—was, in this context, a survival plan.

Yet Reconstruction also exposed the limits of respectability as protection. Education did not immunize Black people against white terror; in some places it made them targets. Institutions like churches and schools were burned. Teachers were threatened. Ministers were attacked. Payne, as a senior church leader, could not have missed the bitter truth: the same society that claimed to value Christian civilization often responded to Black education as though it were an act of war.

In that sense, his project was dual. He was trying to uplift Black communities through learning, and he was trying to build institutions that could absorb blows.

The intellectual in a tradition that needed prophets

Payne was not only an administrator. He was a writer who understood that leadership without narrative control is fragile. His Recollections of Seventy Years—available in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Documenting the American South collection—serves as both memoir and argument: an account of one life, and a case for why education, discipline, and institutional memory mattered.

Memoir is never neutral, and Payne’s is no exception. It is shaped by his theology, his sense of providence, and his belief that the Black church could not afford to drift. But even that subjectivity is instructive. It shows what he feared: not only white supremacy, but internal collapse—charlatanism, disorder, the easy erosion of standards under pressure. And it shows what he hoped: that a Black denomination could generate scholars as well as saints, teachers as well as exhorters.

He also wrote church history, again insisting that Black religious life belonged in the archive. In a period when white institutions were busy manufacturing myths about Black incapacity, Black history-writing became a form of defense.

That defense extended to ecumenical and public life. Payne’s significance appears not only in denominational histories, but in broader cultural references that surface unexpectedly. The Atlantic, writing about Charleston after the Mother Emanuel massacre, invoked Payne’s role in reviving Mother Emanuel during the Civil War era—an example of how his imprint on institutions endured beyond his lifetime.

The point is not that modern essays validate him; it is that the institutions he shaped—churches, colleges, networks—continued to matter, and therefore continued to be remembered.

The conflicts inside the “education gospel”

To write honestly about Payne is to resist hagiography. His accomplishments are real, but so are the tensions his philosophy produced.

One recurring critique, visible in the way historians describe intra-Black religious debates, is that Payne’s push for “order” and formal training could slide into a kind of cultural gatekeeping. When a leader insists on standards, someone inevitably asks: whose standards? Payne’s formation in white-dominated educational and ecclesial spaces helped him acquire tools he used for Black advancement, but it also shaped his aesthetic and theological preferences. His discomfort with certain forms of ecstatic worship, and his efforts to systematize church life, could be read as a bid to align Black religiosity with middle-class norms that white America found more “respectable.” The question is whether that alignment was strategy, conviction, or both.

There is also the political tension that shadows many nineteenth-century Black leaders: what does one do with the dream of integration when the nation repeatedly demonstrates that its promises are conditional? Payne opposed schemes that pushed Black Americans toward emigration, insisting on claims to American belonging. Yet the post-Reconstruction rise of Jim Crow would make “belonging” feel like an accusation. It’s not that Payne was naïve; it’s that he was invested in an American project that kept changing the terms.

Financial struggle is another under-discussed dimension. Black institutions—especially colleges—rarely had stable endowments. Keeping Wilberforce afloat demanded constant fundraising and managerial discipline. That can harden a leader, pushing them toward pragmatism that looks cold from the outside. It can also create conflicts over priorities: do you spend scarce money on classical curricula, on industrial training, on teacher preparation, on theological education? Payne’s belief in broad learning sometimes put him at odds with those who wanted a narrower, immediately “practical” model designed to satisfy white patrons.

And then there is the most unavoidable conflict: the distance between education as personal uplift and education as structural transformation. Payne seemed to believe that disciplined leadership could raise an entire people. But the United States repeatedly demonstrated that Black excellence did not disarm racism; it often provoked it. The “Talented Tenth” logic—however it is framed—can unintentionally place the burden of racial progress on Black people’s performance rather than on the nation’s obligations. Payne did not invent this tension, but he lived inside it.

These critiques do not diminish him. They make him legible.

A life that links three institutions: The school, the church, the college

One of the cleanest ways to understand Payne’s legacy is to see him as a bridge connecting three institutional forms that remain central to Black life: the schoolhouse, the church, and the college. He began as a teacher whose classroom was criminalized by a slave society. He became a bishop who tried to professionalize Black ministry so congregations could be led with intellectual and moral competence. He became a college president who proved that Black governance of higher education was possible even amid national chaos.

Those roles were never separate. Payne treated them as mutually reinforcing. A better-educated clergy could teach and advocate. A stronger church could fund schools. A college could train teachers and ministers. An archive could protect memory. In the nineteenth century, when Black civic life was systematically undermined, this kind of institutional ecosystem was not merely admirable—it was necessary.

That’s why, more than a century after his death, traces of Payne persist in markers, histories, and ongoing institutions that carry his name or reflect his priorities.

The final measure: What Daniel Payne made possible

Payne died in 1893, after serving as bishop for decades. His death came at the edge of a new American order: Reconstruction was long over, and the machinery of segregation was tightening across the South. It would be easy to read that timing as tragic, to imagine that the world he built was about to be crushed by the world that followed.

But Payne’s work suggests a different interpretation. He built institutions precisely because he understood that moods change, laws change, and promises can be revoked. Institutions, while vulnerable, can also be stubborn. They can carry knowledge forward even when the surrounding society is hostile. They can train leaders who outlive the moment. They can store the memory of what a people believed it deserved.

There is a reason Wilberforce’s story remains compelling: not because it avoided struggle, but because it survived it. There is a reason the AME Church remains a central chapter in American religious history: not only because it preached, but because it organized. Payne’s bet was that education could be made into a communal habit—so deeply embedded in Black religious life that it would become difficult to erase.

That bet did not “solve” racism. Nothing one person does can. But it did change the terrain. It helped establish Black higher education as not merely permissible, but normal. It helped normalize the idea that Black institutions should record their own histories and set their own standards. And it offered a model of leadership that refused the false choice between spirituality and intellect.

For a modern reader—especially one thinking about how communities build “cultural infrastructure” that outlasts crises—Payne’s life offers a hard, useful lesson. The most radical thing he did was not simply to believe in Black intelligence. It was to design systems that assumed it, demanded it, and trained it—generation after generation—until the assumption became irreversible.