KOLUMN Magazine

She was among the most consequential organizers of the twentieth century precisely because she insisted that movements could not be built on personality.

She was among the most consequential organizers of the twentieth century precisely because she insisted that movements could not be built on personality.

By KOLUMN Magazine

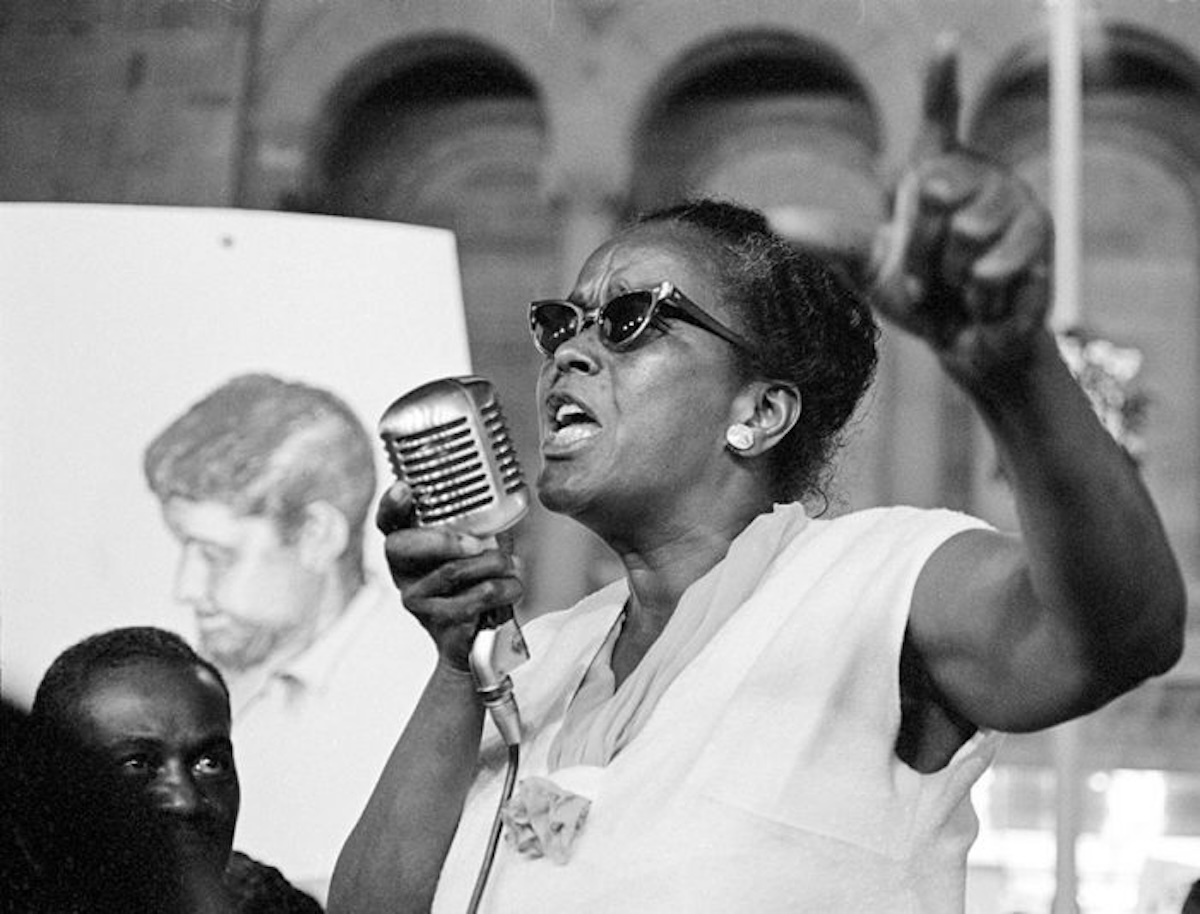

There are lives that announce themselves with banners—names that become shorthand for an era because history loved the drama of a podium, the clarity of a single voice, the cinematic shape of a lone hero confronting a roaring world. And then there are lives like Ella Baker’s: lived in corridors and rented offices, at kitchen tables and in church basements, on long drives between small towns where the stakes were immediate and the credit uncertain. She did not lack courage or vision; she lacked, by choice and by constraint, the kind of public mythology that the United States tends to grant to leadership when it can be easily photographed.

Baker’s genius was structural. She was among the most consequential organizers of the twentieth century precisely because she insisted that movements could not be built on personality. Her focus was not on producing a single luminous figure but on developing durable local leadership—people who could outlast the news cycle and the backlash, people who could keep going when an organization’s national office lost interest, when donors moved on, when fear or exhaustion threatened to shrink a cause back down to private grief. Scholars and historians have described her as a behind-the-scenes strategist with a “radical democratic” sensibility, a woman whose life’s work offers a theory of change as much as a chronicle of campaigns.

To understand Ella Baker is to understand a countertradition inside the civil rights movement—one that prized participatory democracy and group-centered leadership, and that often clashed with the movement’s more charismatic, male-dominated public face. To understand her challenges is to see how that countertradition could be both marginalized and indispensable at the same time: the movement needed Baker’s methods even when it resisted Baker herself.

She was born Ella Josephine Baker in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1903, and she died in New York City in 1986—on her eighty-third birthday, a detail that reads like symbolism but was simply the final coincidence in a life that rarely chased poetic symmetry. Between those dates stretches a long career that began in the political ferment of the interwar years, matured amid the organizational demands of the NAACP, collided with the bureaucracy and gender politics of the early Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and reached its most influential expression when Baker helped midwife a new generation of student activists into what became the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC.

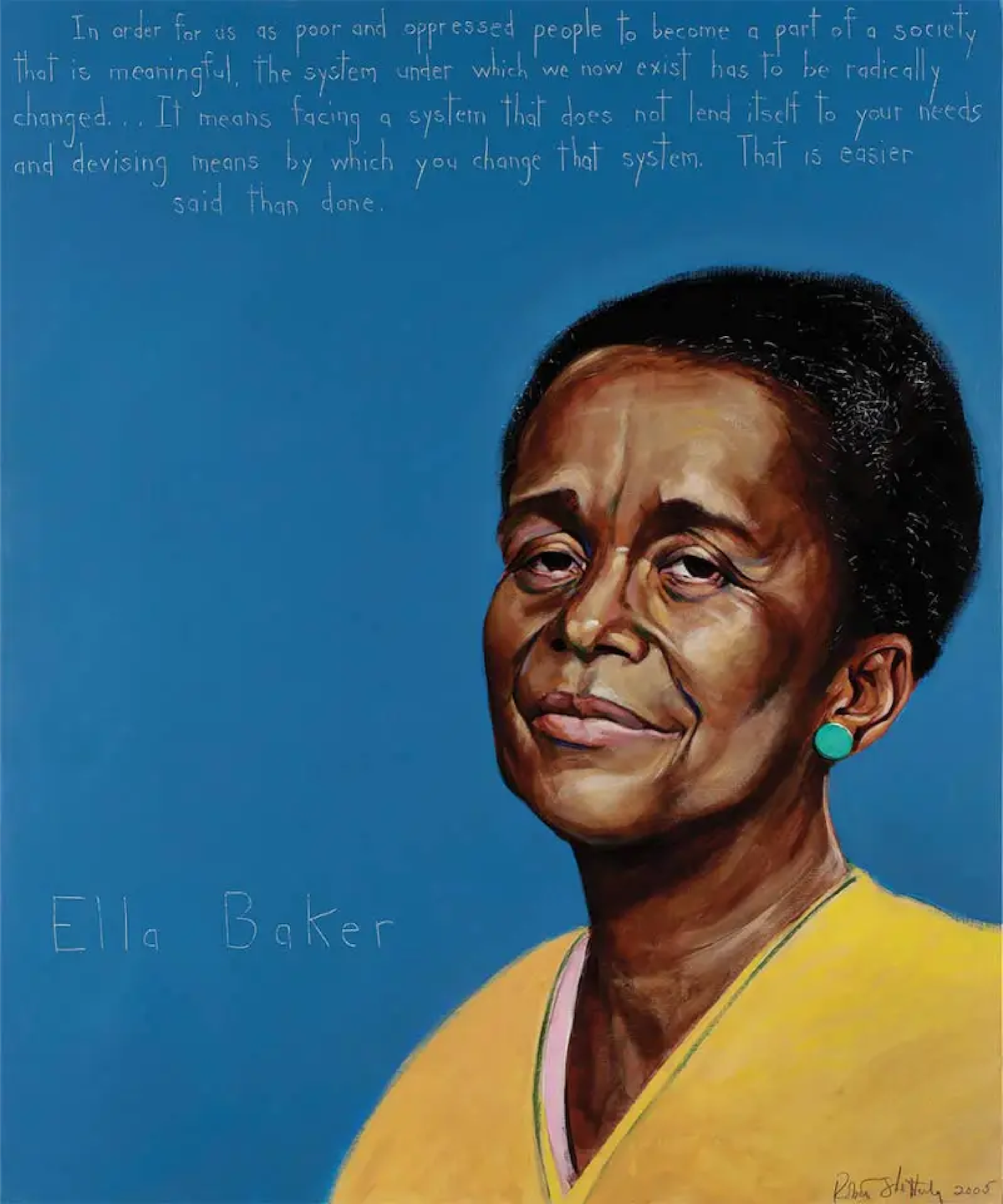

Baker’s fame, such as it is, tends to arrive as quotation—“Strong people don’t need strong leaders”—or as nickname—“Fundi,” a Swahili term associated with a person who passes along a craft. Both are true. Both, on their own, risk turning her into a proverb rather than a person. To treat Baker as a person is to face the daily work she chose: the patient work of persuading ordinary people that their insight mattered and that their participation could be organized into power.

A Southern childhood and an early education in survival

Baker’s childhood and youth are often summarized quickly—Norfolk, then North Carolina, then Shaw University—but the arc matters because it shaped the instincts that would define her: skepticism toward authority, a preference for practical problem-solving, and an ethic of community responsibility that did not require applause.

She attended Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, graduating in 1927. Shaw would return later in her story, not merely as an alma mater but as a staging ground for one of the movement’s most important generational handoffs. Decades after her graduation, Baker would summon student sit-in leaders to Shaw, encourage them not to become an “auxiliary” of older organizations, and help set the conditions for SNCC’s founding. In other words, she returned to the place that helped train her mind and used it to help train a movement.

Biographical summaries can make Baker’s early years feel like prologue, but the interwar period and the Great Depression were formative. Baker’s organizing temperament developed in a world where Black communities confronted both overt terror and quieter forms of economic coercion. This mattered because Baker never treated civil rights as purely symbolic. Voting rights, desegregation, and legal equality mattered, but so did the daily terms of life: work, housing, education, and dignity. That breadth of concern—civil rights as inseparable from economic and social justice—would later place her at odds with organizations that wanted to keep their mission narrow for strategic or fundraising reasons.

Harlem and the politics of cooperative life

When Baker moved into the political milieu of New York City, she entered a world that offered both intellectual electricity and practical lessons in organizing. Harlem in the 1930s was not only a cultural capital but also a laboratory for political arguments—about capitalism and cooperatives, about labor and race, about international solidarity, about whether Black freedom could be achieved within existing institutions or required a deeper transformation.

Baker’s early work included involvement in the Young Negroes’ Cooperative League, an effort oriented toward economic cooperation and collective Black economic power. In that setting, she learned an enduring lesson: that “leadership” could be less about charisma than about education and infrastructure—teaching people how to run meetings, manage finances, sustain membership, resolve internal conflict, and build alternatives when the mainstream market exploited or excluded them. The cooperative tradition also trained Baker’s suspicion of savior politics. Cooperation, by definition, required shared agency.

She also worked in educational programs connected to the New Deal era, teaching and facilitating learning that linked personal experiences to political structures. That orientation toward political education—helping people interpret their conditions and see themselves as actors—would remain central to her organizing philosophy. It is not accidental that later scholars would argue that Baker’s practice embodies an ideology of radical democracy, one that treats ordinary people as capable of analysis and leadership when the right structures exist.

In these years, Baker moved within a broader progressive ecosystem. She engaged issues beyond the South, and beyond the legalistic frame that would later dominate popular memory of the civil rights movement. Her politics were never only regional; they were rooted in a belief that power is built through participation and that oppression is maintained through isolation. The organizer’s job, as she saw it, was to break that isolation with relationships and structures.

The NAACP: Building branches, building capacity

If Baker had wanted a public-facing career, the NAACP might have offered a platform. Instead, it became her proving ground in a different sense: a place where she could develop the craft of large-scale organizing, especially the painstaking work of building and sustaining local branches.

Baker served in significant roles within the NAACP, including work focused on branch development. The task sounds administrative until you imagine its geography and its danger: building membership in places where joining the NAACP could cost someone their job or invite violence; traveling through communities where local power was explicitly invested in keeping Black citizens politically weak; turning grievances into agendas, and agendas into sustainable local organizations.

Branch work forced Baker to reconcile two realities. First, national organizations often need uniform strategies, clear messaging, and centralized control in order to move money and win legal or legislative victories. Second, local communities rarely experience oppression uniformly, and their most urgent needs are not always those that appear on national letterhead. Baker’s gift was to treat local knowledge as the movement’s intelligence rather than its inconvenience.

Her approach also placed her in a recurring predicament: she was invaluable precisely because she built other people’s capacity, which meant her success could be measured in the visibility of others rather than in her own acclaim. In a political culture that credits leaders and downplays organizers, Baker’s role was structurally hard to celebrate.

The creation myth of modern civil rights leadership—and Baker’s dissent

The mid-century civil rights movement is often narrated through its most famous institutions and figures: the rise of Martin Luther King Jr., the emergence of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the moral drama of segregation confronted by nonviolent protest. Baker was deeply involved in the movement’s organizational ecology, but she also became one of its most incisive internal critics.

In accounts that examine the movement’s “hidden women,” Baker appears as a key figure whose work spanned the NAACP and the SCLC. She moved into SCLC work in the late 1950s, becoming a crucial staff presence at a formative moment for the organization. The SCLC was, in many ways, built around a leadership model that the public found legible: ministers, charisma, speeches, and a moral narrative centered on a few recognizable faces. Baker respected the ministers’ courage but resisted the organizational consequences of that model.

What were her challenges here? Some were logistical: a young organization struggling to build infrastructure, manage funds, and translate a moment of protest into a long-term program. But some were deeper, rooted in gender and hierarchy. Baker’s temperament—direct, pragmatic, insistent on process—did not always fit the expectations placed on women in male-led institutions. The Washington Post, reflecting on movement history, has described the reverence young activists held for Baker and noted that she was never given senior position in the movement because she was a woman. That blunt assessment captures a recurring tension: Baker’s competence did not guarantee authority.

Baker’s critique of “charismatic” leadership was not an abstract intellectual preference; it was forged in daily experience. A movement that depends on a single figure can be vulnerable: to assassination, to imprisonment, to burnout, to ego, to the distortions of celebrity. A movement that builds many leaders—especially local leaders—has redundancy, resilience, and the possibility of genuine democracy rather than symbolic representation.

This critique did not make Baker anti-leader; it made her pro-people. Leadership, in her view, should be a function, not a personality cult. It should circulate. It should be accountable.

The student sit-ins and the moment Baker helped create

The turn that cemented Baker’s legacy arrived with the student sit-in movement of 1960. Young Black students across the South were challenging segregation directly, in public, often at great personal risk. Older civil rights organizations recognized the sit-ins’ potential but also saw them as an opportunity to recruit youthful energy into existing structures.

Baker saw something else: a chance for young people to build their own organization, their own political culture, and their own leadership model.

She organized a convening at Shaw University in Raleigh in April 1960, bringing together sit-in leaders and encouraging them to remain autonomous rather than become a subordinate wing of older organizations. This conference is widely recognized as the seedbed for SNCC’s founding. Shaw University itself commemorates the gathering and Baker’s role, emphasizing that she organized the meeting and that it culminated in SNCC’s formation. Stanford’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute similarly describes Baker inviting student activists, urging them toward a student-run, locally based organization, and encouraging autonomy. SNCC’s own digital history records the tension at the conference—pressure from SCLC representatives for affiliation, Baker’s insistence on independence—and the outcome: an emerging organization that would become one of the movement’s most innovative forces.

This was not merely an organizational footnote. SNCC would pioneer participatory approaches and place local leadership at the center of its work in the Deep South. The students’ decision to remain independent changed the internal balance of the movement. It created a space where young organizers could experiment, make mistakes, argue openly, and develop a leadership model less tethered to respectability politics and more responsive to the realities of rural Black communities.

Baker gave them something concrete as well: space and support. SNCC’s historical materials note that she provided them room in Atlanta at the SCLC office, a practical act that signaled her role not as an owner of the organization but as a facilitator of its emergence.

If there is a single scene in Baker’s story that captures her method, it is this: not the delivery of a grand speech but the creation of a room in which others could decide, collectively, what they would become.

Participatory democracy: A philosophy built from practice

“Participatory democracy” can sound like academic jargon, but for Baker it was as concrete as a meeting agenda. It meant that people most affected by injustice should have meaningful power in deciding how to fight it. It meant minimizing hierarchy that treats expertise as a substitute for lived experience. It meant direct action not as performance but as a way to dissolve fear and isolation.

Political scientists have treated Baker’s thought as a serious theory of organizing, arguing that her ideology of radical democracy shaped her approach to mass action and indigenous leadership. That scholarship matters not because it grants Baker intellectual legitimacy—she did not need it—but because it clarifies what many activists sensed: Baker’s practice was a coherent worldview, not mere temperament.

The implications were enormous. A participatory approach changes the relationship between a movement and its base. The “base” is not a crowd summoned for a march; it is a community engaged in decision-making, trained in skills, and capable of sustaining action. This is slower than spectacle. It is also, as Baker understood, more durable.

Baker’s insistence on participation was also a gender critique, whether framed that way publicly or not. Male-centered leadership models often reward performance—speech, posture, public authority—while treating the relational labor of organizing as secondary. Baker’s worldview elevated that labor. It treated the work of building relationships, training leaders, and resolving internal conflict as central—not supportive.

The cost of being indispensable and undervalued

Baker’s challenges were not limited to external opposition. She faced the movement’s internal contradictions: sexism, class tensions, generational conflict, and ideological policing in the Cold War era.

Sexism was not merely interpersonal; it was institutional. To be a woman with strong opinions and organizational power in a movement culture shaped by male clergy and male public leadership was to be regularly positioned as “help” rather than strategist. Baker did not accept that role quietly, but resistance came at a cost. The more she challenged hierarchy, the less likely she was to be rewarded by it.

Cold War politics added another layer. Progressive organizers often faced red-baiting—accusations meant to isolate them, cut off resources, and delegitimize their critiques. Baker’s own commitments—broad solidarity, skepticism of capitalist exploitation, willingness to engage a range of progressive causes—could make her vulnerable in an era when “respectability” was sometimes treated as a survival strategy.

Then there was the simple strain of the work. Organizing is physically exhausting: constant travel, long meetings, crisis management, the emotional labor of holding other people’s fear and grief. Baker was doing this work for decades. By the time SNCC emerged, she was not a young woman in her twenties; she was a seasoned organizer with decades behind her, stepping into a mentoring role that required both humility and stamina.

SNCC, Freedom Summer, and the moral stress of American democracy

SNCC’s work in the 1960s—voter registration, community organizing, political education, and the cultivation of local leadership—pushed the movement into places where legal victories did not immediately translate into safety or power. Baker’s influence is often described as foundational to SNCC’s group-centered ethos. SNCC history emphasizes that she recognized the sit-in movement’s potential and encouraged students to commit fully to the freedom struggle, in contrast to adult leaders who wanted control.

The mid-1960s also brought intense confrontation with the Democratic Party’s limits and the nation’s reluctance to confront structural racism. While a full accounting of Baker’s role across every campaign would require book-length treatment, one can trace her consistent commitments: to local people as the movement’s core, to organizing as education, and to democracy as practice rather than promise.

Her later reputation among younger activists also speaks to the particular moral authority she carried: she was seen as someone who did not chase credit, who did not treat leadership as ownership, and who did not confuse national access with local accountability. That reputation is one reason her legacy has remained potent even as the movement’s mainstream narratives long focused elsewhere.

“Fundi,” mentorship, and the art of teaching adults to trust themselves

Baker’s nickname—“Fundi”—is often invoked to capture her role as a mentor. The Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, an organization named in her honor, highlights the meaning of “Fundi” as a teacher of craft to the next generation, emphasizing her continuing influence and the mentoring dimension of her leadership. The nickname matters because it reveals how those around her experienced her: as someone who transmitted methods, not slogans.

Mentorship, in Baker’s model, was not paternalistic. It did not mean instructing young activists to reproduce her decisions. It meant helping them develop their own judgment, their own political confidence, and their own capacity to withstand pressure. It meant refusing to become the center of the story so that others could become the center of their own.

That model stands in contrast to a popular caricature of movements as leaderless or spontaneous. Baker did not believe in leaderlessness; she believed in leaderfulness—many leaders, developed intentionally, distributed across communities, trained through action and reflection.

A long life in coalition: Beyond the movement’s most famous decade

Popular memory often traps civil rights leaders in the 1950s and 1960s, as if their political lives ended when the cameras moved on. Baker’s career spanned from the late 1920s through her death in 1986, and archival guides emphasize the breadth of her organizational affiliations and progressive commitments. The New York Public Library’s archival materials describe her papers as a snapshot of her life as an activist and visionary across a wide range of progressive organizations, reflecting decades of involvement.

Baker’s later years included continued engagement with human rights struggles, and her legacy has been interpreted as connecting civil rights to broader movements for social transformation. The point is not to create an all-encompassing list of causes but to recognize a throughline: Baker treated freedom as a living practice that demanded attention to new forms of oppression and new coalitions.

Her influence, therefore, is not confined to SNCC or even to civil rights as conventionally defined. It appears in modern organizing traditions that prioritize base-building, leadership development, and participatory decision-making.

Why Baker was obscured—and why she endures

It is tempting to interpret Baker’s relative obscurity as an accident, a failure of historical storytelling that can be corrected simply by repeating her name more often. The truth is harsher and more instructive: Baker was obscured because her kind of power is harder to narrate in a culture that prizes spectacle. Movements, like nations, prefer myths with a single protagonist.

Baker also posed an implicit critique of that mythmaking. Her approach suggested that hero worship is not just aesthetically misleading; it can be politically dangerous. It invites passivity in the very people a movement needs to activate.

Yet Baker’s ideas have proven stubbornly reusable. The language of participatory democracy, the emphasis on organizing rather than mobilizing, the insistence that local people must lead their own struggles—these concepts recur across generations because they describe reality. They describe how power changes hands.

Even mainstream political commentary sometimes returns to Baker when trying to name what durable coalition-building looks like. Washington Post essays have invoked her as an “enormous political force” who pushed activists to practice democracy “from the bottom up,” underscoring how her method remains relevant beyond the civil rights era.

The personal discipline of an unglamorous politics

One of the more difficult tasks for any profile of Baker is to capture her interior life without turning her into either saint or scold. Baker could be sharp. She could be impatient with vanity. She could be unsentimental about organizations that substituted symbolism for structure. But those traits were inseparable from her discipline. She believed the stakes were too high for performance.

Her discipline also appeared in her willingness to do “small” work. A movement is often imagined as a series of great events—boycotts, marches, landmark laws. Baker understood that the movement’s fate was decided just as often by the quality of its meetings, the clarity of its roles, the honesty of its internal culture, and the training of its members. This is why she cared about rules, structure, and operating order, and why tributes to her often emphasize that she was the person trying to build organizational systems rather than chase headlines.

There is a kind of moral realism in that orientation. Baker seemed to recognize that the United States could concede symbolic victories while leaving deeper structures intact. Organizing, to her, was the mechanism by which people learned to identify those structures and contest them over time.

Ella Baker in a culture that still prefers icons

To write about Baker now is to write about how we remember political change. Her life forces a question that remains contemporary: do we want democracy as a ceremony, performed every few years and narrated through a handful of prominent names, or do we want democracy as a daily practice that requires participation, training, and conflict?

The scholarship on Baker suggests that her theory of organizing remains a resource precisely because it does not depend on the unique conditions of the 1960s. It depends on human dynamics that persist: people are often isolated; power often relies on that isolation; change requires relationships; relationships require time; time requires organizations; and organizations require structures that distribute rather than hoard leadership.

Baker’s challenge—then and now—was that this approach can be frustratingly unmarketable. Donors like measurable wins. Media likes singular protagonists. Institutions like clear chains of command. Participatory democracy can look messy from the outside because it is, by nature, a practice of collective decision-making among imperfect people.

But its messiness is also its strength. It creates buy-in. It develops skills. It produces leaders who can operate without permission.

Legacy: A name, a method, a demand

Baker’s legacy is visible in formal commemorations and institutions—archives, biographies, organizations named in her honor—and in the quieter ways movements adopt her approach.

Her papers at the New York Public Library, for example, preserve the documentary evidence of a life spent building progressive infrastructure. The very existence of such archives is a reminder that Baker’s work was not ephemeral: it was made of documents, memos, letters, strategy debates—the mundane materials of collective action.

Her legacy also lives in how new generations narrate organizing itself. Ebony, in a piece about unsung feminist civil rights leaders, describes Baker as integral to the movement and emphasizes her preference to be “felt, not seen,” a phrasing that captures both her choice and the cultural forces that later made her easier to overlook.

And her legacy lives, perhaps most importantly, in the persistent return of her central insistence: that strong people do not need strong leaders. They need opportunities to learn, structures to participate, and the collective confidence to act.

Baker’s life is sometimes used to correct the record of a movement that has too often been narrated as male, ministerial, and singular. But correcting the record is only the beginning. Baker does not merely deserve recognition; she offers instruction. She tells us that history changes when ordinary people are treated as capable of governing their own struggle—and when someone, somewhere, does the unglamorous work of building the room where that governance can begin.