KOLUMN Magazine

The weight of being a public face after private grief.

The weight of being a public face after private grief.

By KOLUMN Magazine

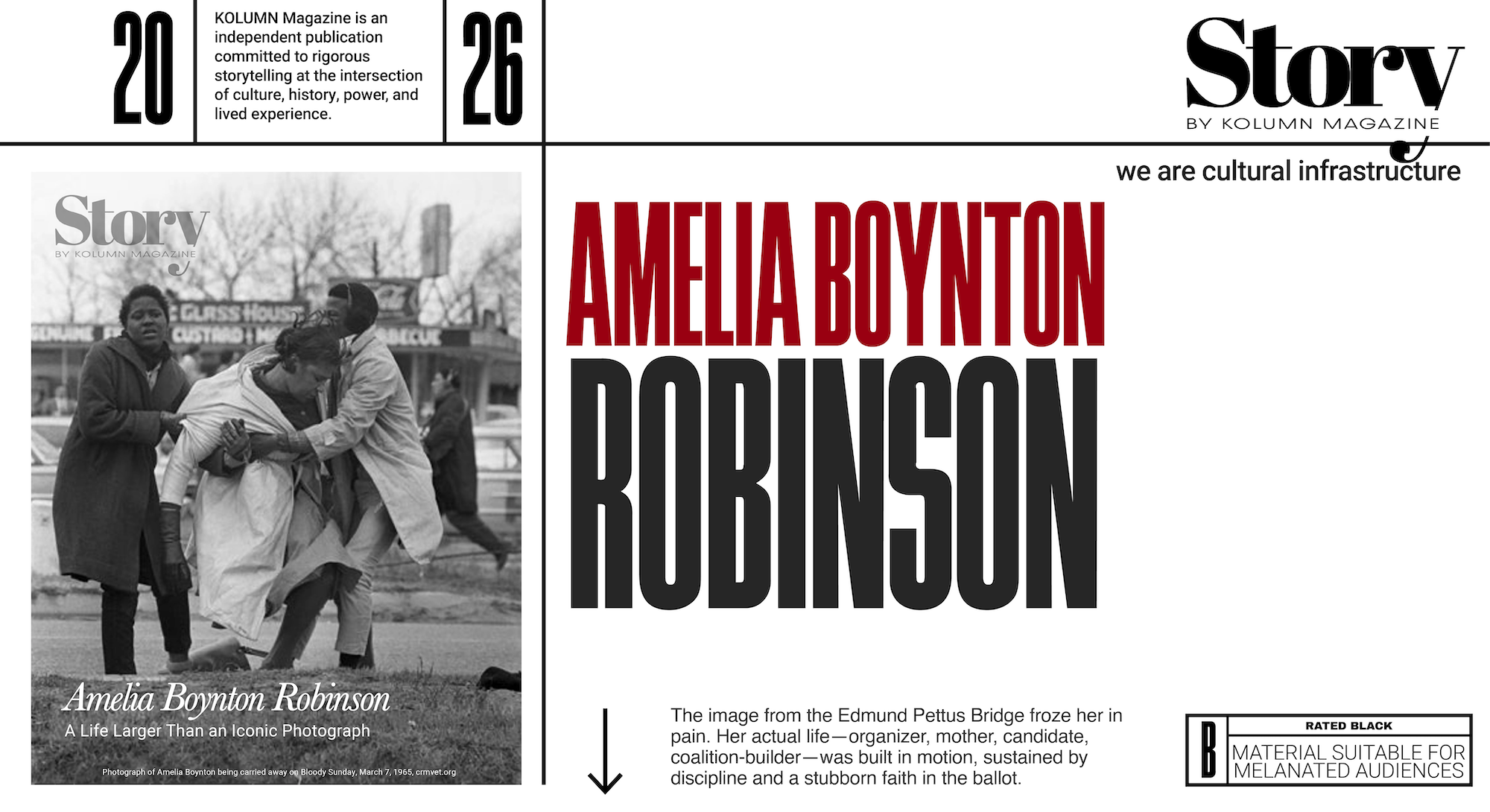

The photograph is so familiar that it can feel like the beginning of the story. Amelia Boynton Robinson lies on the hard surface of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, her body slack, her coat bright against the roadway, the violence of the state hovering just out of frame. The image—circulated in newspapers, replayed in anniversary documentaries, pinned to the national memory of March 1965—helped turn “Bloody Sunday” into a moral verdict against voter suppression. The problem with an image that powerful is that it can flatten the person inside it. It can turn a life into a single, terrible minute.

Boynton Robinson’s story, in truth, began long before the bridge and continued long after it. She was not simply an injured marcher who became an emblem; she was a strategist who helped make Selma a national confrontation, a public servant who learned the machinery of rural poverty from the inside, and a political actor who attempted—openly, audaciously—to convert protest energy into electoral leverage. The photograph captured what happened to her body. It did not capture the decades that trained her for that moment, or the years of resilience required to live as a symbol without being consumed by it.

To write about Amelia Boynton Robinson honestly is to resist the temptation of a single climax. It is to understand Selma as more than a stage for visiting leaders and television cameras, and to see how a local Black woman—working in a county designed to deny Black citizenship—built the relationships, routines, and moral authority that made a national movement possible. It is also to tell the story with the weight that leadership placed on her shoulders: the weight of being a public face after private grief, the weight of being one of the “safe houses” of a campaign that could get people killed, the weight of being the kind of person history wants to turn into a statue even while she was still alive, walking, organizing, persuading, disagreeing, and enduring.

The early lessons: Dignity, discipline, and the politics of “home”

Boynton Robinson was born Amelia Isadora Platts in Savannah, Georgia, and came of age in the early twentieth century, when the South’s legal architecture was arranged to keep Black people economically dependent and politically mute. Later, when she spoke about the world she grew up observing, she described a social order that trained Black families to survive by compliance—and trained white institutions to treat that survival as consent. In an interview recorded for the documentary project Eyes on the Prize, she recalled a world where Black people were expected to remain in servile roles and where poverty could be made to feel like fate rather than policy.

If the movement years would later be narrated through marches and speeches, Boynton Robinson’s formative period points to a different kind of political education: the politics embedded in daily life. She studied at Tuskegee Institute, trained in home economics, and entered public work through agricultural and extension programs. In Selma, she served as a home demonstration agent connected to federal and county agricultural systems—an official role that brought her into contact with rural Black families navigating hunger, debt, and fragile health. The work required trust, tact, and endurance: traveling roads, speaking in kitchens and church basements, explaining nutrition and food preservation, and witnessing how the state’s racial hierarchy determined who had access to land, credit, and care.

This is not incidental background. For Boynton Robinson, “home” was not merely domestic space; it was the first arena of citizenship. The extension agent’s toolkit—listening closely, translating policy into practical survival, persuading families to try new methods, building networks through women’s organizations—was also an organizer’s toolkit. She learned how to move through systems that were not designed for her, how to use official titles without being captured by official limits, and how to build power without announcing it in ways the local white establishment could immediately crush.

Selma before it was famous: The local architecture of repression

By the time America’s cameras arrived in Selma, the city and Dallas County had already been “famous” to its Black residents for a different reason: it was a place where the vote had been functionally stolen. The mechanisms were familiar across the Jim Crow South—literacy tests, intimidation, economic retaliation, bureaucratic gamesmanship—but their local expression could be uniquely punishing. When outside organizers from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) arrived in the early 1960s, they found in Boynton Robinson and her husband, Samuel William “S.W.” Boynton, people who had already been doing the long work. SNCC’s digital archive describes the Boyntons as prepared, active, and ready—Selma residents who had been pushing long before national attention made it seem fashionable.

The Boynton home became more than a residence. It functioned as infrastructure: a place for meetings, planning, and the quiet logistics that keep a movement alive. To host people in Selma—especially organizers and clergy—meant accepting surveillance and threat. It meant being the kind of person whose phone might ring with warnings or whose economic security could be targeted. It also meant something else that histories often understate: it meant managing fear in the presence of others. An organizer’s house is where young activists come to breathe, where strategy debates can turn sharp, where someone might cry in a back room after an arrest or a beating, where the movement’s public righteousness meets private exhaustion.

Boynton Robinson was, by temperament and practice, a bridge figure—between local and national, between women’s civic work and mass movement politics, between federal “service” roles and grassroots insurgency. Her credibility was built in the slow accumulation of trust. She and her allies in the Dallas County Voters League were working to turn citizenship into an everyday act rather than a distant ideal, even as local power treated Black political ambition as an invasion.

The letter, the invitation, the decision to call the world in

Selma did not become Selma by accident. It became a national pivot because local people—Boynton Robinson among them—helped decide that it had to. Later accounts of the movement often describe an invitation that helped bring the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and Martin Luther King Jr. into Selma’s voting rights fight. In contemporary retellings, Boynton Robinson is frequently identified as one of the key local figures urging national leadership to bring attention to the city’s voter suppression. The point is not to reduce a complex strategy to a single letter; it is to recognize what the act represented. To invite the nation into Selma was to escalate the confrontation—to accept that greater visibility could mean greater danger.

That choice carried a particular weight for a Black woman rooted in the community. Visiting leaders could leave. Local people had to stay. If the sheriff or local power brokers retaliated, they retaliated against the people who lived there, whose children went to school there, whose mortgages and jobs were vulnerable there. Boynton Robinson’s courage was not only in marching; it was in helping set the stage for confrontation, knowing that the bill would be paid locally.

The personal blow that became political weight: Loss and leadership

In 1963, S.W. Boynton died. For Amelia Boynton Robinson, grief did not arrive as a pause in public life. It arrived as a transfer of weight. Widows of movement work are often described in the sentimental language of strength, but strength is not a personality trait; it is a set of obligations that do not go away when someone dies. Losing a spouse can mean losing an organizer partner, a co-strategist, a buffer against loneliness and fear. It can also mean losing economic stability in a society designed to punish Black families financially. Boynton Robinson—already deeply engaged—found herself carrying more of the movement’s operational responsibilities at a moment when the struggle in Selma was intensifying.

This is where her resilience becomes tangible. The narrative of the civil rights movement sometimes implies that national momentum sweeps people into history. Boynton Robinson’s life suggests something harder: history often arrives when you are already burdened, and then it asks for more. Her home continued to function as a locus of organizing and planning. She continued to work with local and national allies. She continued, in other words, to convert private pain into public purpose—a conversion that is admired in retrospect but is brutal to live through in real time.

“Bloody Sunday”: The day the state made her body a message

March 7, 1965, was not the first act of repression in Selma, but it was the day the repression became legible to the broadest American public. Around 600 marchers attempted to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge to begin a march from Selma to Montgomery, protesting the denial of voting rights. On the far side of the bridge, Alabama state troopers and local law enforcement confronted the demonstrators. What followed was violence that looked, on television and in photographs, like the state’s confession: tear gas, clubs, mounted officers, bodies falling.

Boynton Robinson was beaten unconscious. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) notes that she was brutally beaten by state troopers during the march and that the photograph of her helped draw national attention. That is true—and still insufficient. The assault was not only against her; it was against the premise that Black citizens could assemble and petition for rights without being physically punished. The point of public violence is to discipline an entire community by demonstrating what can happen to one person. When the person is a middle-aged Black woman and a local leader, the message is calibrated: if even she can be beaten down, anyone can.

The brutality also produced an unintended counter-message. Photojournalism—images that could not be explained away—became part of the movement’s arsenal. The Guardian, in later coverage of restored “Bloody Sunday” photographs and exhibitions, underscored how imagery of the violence shocked the nation and helped build support for voting rights. Boynton Robinson’s injured body became, against her will, a catalyst: a visual argument that made “voter suppression” feel like more than a procedural dispute. It looked like blood and lawlessness, carried out by uniforms.

There is a temptation to treat this as the story’s climax: a courageous woman attacked, a nation awakened, a law passed. But Boynton Robinson’s resilience is clearer when you consider what it means to survive becoming an icon of pain. Her body recovered, but symbols do not get to recover in the same way. A symbol must remain available to other people’s needs—commemorations, speeches, anniversaries, and the public’s hunger for moral clarity.

After the bridge: Converting momentum into political agency

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is often presented as the legislative resolution to Selma. In reality, it was the opening of a new chapter, not the end. Communities had to register voters, protect them, teach them the mechanics of elections, and fight backlash that could be subtle or violent. Boynton Robinson understood that the vote was not only a moral claim; it was a tool for redistribution of power. And she had already attempted, before the act’s passage, to model what Black political aspiration could look like in Alabama.

In 1964, she ran for Congress, becoming the first Black woman in Alabama to run for the office and, in many accounts, the first woman to run as a Democrat for Congress in the state. She did not win, but the campaign functioned as a provocation: it forced the state to confront Black political ambition not as a hypothetical future but as a present reality. The Washington Post obituary notes her voting rights work, her organizing, and her congressional run, framing her as a figure who tried to translate the movement into formal politics.

Running for office in a place like Alabama in the mid-1960s was itself a form of resistance. It required standing publicly in a society built to punish Black visibility. It required asking people—many of whom had been terrorized for trying to register—to imagine themselves as voters whose choices mattered. It required, too, a willingness to accept ridicule, threats, and political isolation. Electoral politics can be lonely; losing can be brutal; and for a Black woman at that time, the scrutiny came layered with sexism and racism. Boynton Robinson did it anyway.

This is part of the resilience that does not fit neatly into the photograph. To be beaten by the state and then continue to believe, in practical terms, in the value of the ballot is not sentimental optimism; it is a disciplined refusal to surrender the field.

Motherhood and movement: The private costs behind public courage

Any honest account of Boynton Robinson must treat family as central, not peripheral. The movement years demanded travel, meetings, late nights, and constant emotional labor. For women, that labor was often doubled by caretaking responsibilities that did not pause for history. Boynton Robinson raised children and helped care for family while functioning as a local anchor for one of the most consequential voting rights campaigns in American life.

Her family also encountered the movement’s stakes directly. One of her sons, Bruce Carver Boynton, became associated with a key legal case after being arrested during a trip in Virginia—an incident connected to the broader struggle against segregation in interstate travel. For Boynton Robinson, these were not abstract “issues.” They were the conditions that reached into a mother’s life and demanded choices: when to push forward, when to protect, when to keep going even as fear for your children becomes its own form of captivity.

The weight on her shoulders, then, was not only that of a local movement leader. It was the weight of a parent trying to widen the world for her children while knowing that the push itself could endanger them. It is easy, in retrospective storytelling, to describe such women as fearless. More accurate is to say they learned to live with fear without granting it authority.

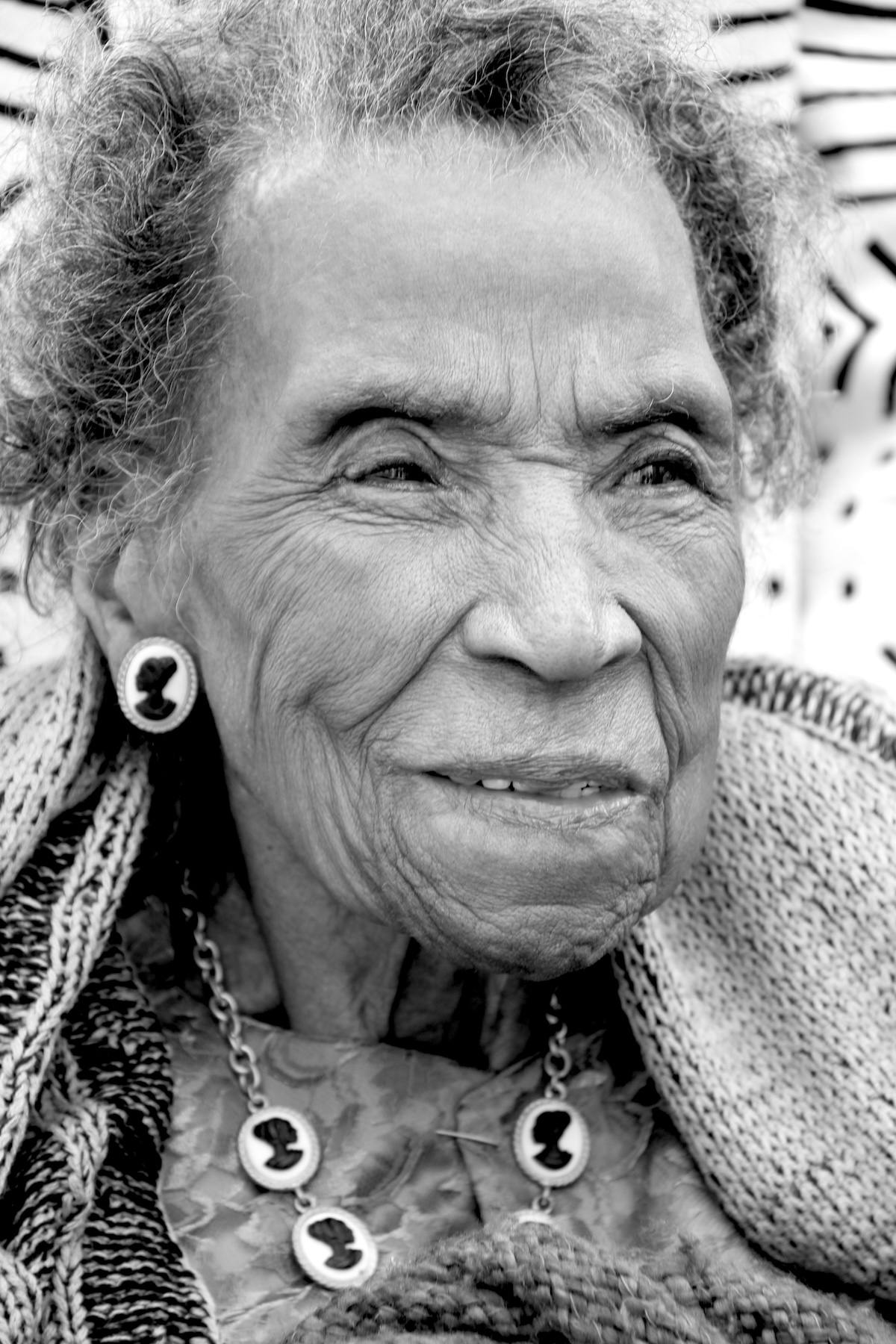

Living long enough to watch history change—and repeat

Boynton Robinson lived into her second century, long enough to witness the civil rights movement become curriculum, museum exhibit, and political shorthand. She also lived long enough to see voting rights become contested terrain again—through legal battles, district maps, ID laws, and the rhetorical normalization of suspicion toward the electorate. The moral drama of Selma never fully ended; it changed costumes.

In 2015, during the 50th anniversary commemorations of “Bloody Sunday,” she walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge with President Barack Obama—an image heavy with symbolism: a Black president holding hands with a woman who had been beaten there by the state. The Washington Post described her attendance at Obama’s State of the Union that year and captured her insistence, spoken with careful emphasis, that the country should be “a United States”—a phrase that carried both hope and indictment.

Obama’s statement on her death later that year framed her as a lifelong defender of voting rights who “kept marching” to ensure barriers to the polls were removed. The language is presidential and polished, but it captures an essential truth: Boynton Robinson’s work was never only about one moment. She treated democracy as something that had to be maintained, not merely achieved once.

The Equal Justice Initiative, marking her death, called her a matriarch of the voting rights movement. The word “matriarch” can sometimes soften political sharpness into familial warmth. In Boynton Robinson’s case, it can also be read as recognition that she embodied a particular kind of authority: the authority of someone who did not need fame to lead, who understood the movement as long work, and who stayed rooted in place when others came and went.

The complications: Affiliation, legacy, and the risks of simplification

Respected news media profiles must also acknowledge complexity and controversy without sensationalism. In later life, Boynton Robinson became affiliated with the Schiller Institute, an organization connected to Lyndon LaRouche, a polarizing political figure. The fact of that association appears in mainstream biographical summaries and complicates the tendency to render civil rights elders as uncomplicated saints. Lives are long. Coalitions shift. People make choices that admirers do not always understand or endorse.

Acknowledging this does not diminish her foundational work in Selma. It does, however, push readers to treat historical actors as human beings rather than as moral mascots. The danger of civil rights iconography is that it can encourage the public to love the symbols while ignoring the ongoing political fights those symbols demand. Boynton Robinson’s life suggests a different approach: honor the courage, study the strategy, and keep the focus on the structural problem she spent her life confronting—restricted access to political power.

What her life teaches about resilience

Resilience, in Boynton Robinson’s story, is not a motivational slogan. It is visible in specific acts.

It is the resilience of sustained civic work: the years of meetings, trainings, conversations, and registrations that rarely make headlines. It is the resilience of being a Black woman with an official role in a segregated society, navigating white institutions while serving Black communities. It is the resilience of continuing after her husband’s death, carrying both grief and responsibility in the same hands. It is the resilience of surviving state violence and then returning, again and again, to the idea that the vote is worth the cost.

It is also the resilience of refusing to be reduced. The photograph from the bridge made her famous in a way that could have trapped her in a single identity: victim. But her life’s full arc insists on other nouns: organizer, strategist, candidate, mother, elder, witness. If the image is a national icon, the life behind it is a blueprint for how local people manufacture national change.

Selma is often narrated as a moment when America found its conscience. Boynton Robinson’s story suggests something more precise and less flattering: America’s conscience was forced into visibility by people who understood, long before television did, that citizenship without access is a lie. She helped engineer that forcing. She paid for it in blood and in decades of living with what the photograph could not show: the ongoing work of building a “United States” in the places most determined to remain divided.