The mountain will keep forcing the same question. Not what we remember, but who gets to decide what remembrance looks like, and what price the rest of the public pays for that decision.

The mountain will keep forcing the same question. Not what we remember, but who gets to decide what remembrance looks like, and what price the rest of the public pays for that decision.

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a clear day outside Atlanta, Stone Mountain reads like a natural monument before it reads like a political one: a vast granite dome rising from the Georgia Piedmont, a landmark visible from highway interchanges and neighborhood cul-de-sacs, its slopes catching morning light the way older landscapes do—quietly, almost stubbornly. For generations, families have brought strollers and coolers here, hiked the footpaths, watched fireworks, and pointed children toward the summit as if to say: this is ours; this is where we live.

Then the mountain turns its other face.

On the north side, carved into the rock at a scale that overwhelms ordinary perception, are three Confederate leaders—Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson—etched in a bas-relief that has long been billed as the largest Confederate monument in the United States. The carving, and the park that frames it, sit at the intersection of American leisure and American mythmaking, where tourism, state power, and the politics of race have been braided together for more than a century.

That is what makes Stone Mountain so difficult to summarize and so hard to “fix.” It is not only a rock face with a sculpture. It is a site where the revived Ku Klux Klan staged its rebirth in 1915, where cross burnings became public spectacle, and where the long campaign to inscribe the Confederacy into the landscape moved forward in fits and starts—then surged again in the era of massive resistance to desegregation. It is also a public park in a majority-Black metro region, a place where school field trips and family reunions can unfold under iconography built to sanctify a slaveholders’ republic. It is, in other words, a paradox made into infrastructure.

To understand Stone Mountain’s relationship with the Ku Klux Klan is to confront a broader American pattern: extremist movements rarely operate only from the shadows. They recruit, ritualize, and normalize themselves in public—through pageantry, fundraising, civic partnerships, sympathetic lawmakers, and the careful use of “heritage” language that drains violence from history. At Stone Mountain, the Klan did not merely pass through. The mountain was central to its modern reinvention, and the memorial project that followed grew in the same ideological soil.

What follows is a history of how that happened, why it still matters, and why the question of “what should be done” remains so fraught in Georgia and beyond.

A Landmark Before It Was a Symbol

Stone Mountain is often described in tourist brochures as a natural wonder, a geological dome that predates the nation by unimaginably long spans of time. That framing is not wrong, but it is incomplete. The mountain has always been more than a view. Like many prominent landscapes in the South, it has been used—economically, culturally, politically—by whoever had the power to define its meaning.

Long before it became a theme-park destination, the mountain was a working landscape. Granite quarrying helped fuel regional building booms, and the mountain’s stone traveled outward into civic architecture. The mountain also sits in a county shaped by the churn of metro Atlanta—suburbanization, demographic change, and the modern Sun Belt economy.

But Stone Mountain’s modern national meaning did not come from geology or quarrying. It came from a choice, made in the early twentieth century, to treat the Confederacy not as a defeated rebellion built to preserve slavery, but as a sacred inheritance worthy of monumentalization. That choice was not inevitable. It was a political project.

The Lost Cause Finds a Canvas

The campaign to monumentalize the Confederacy surged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, driven by organizations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), sympathetic civic elites, and a regional commitment to rewriting the Civil War as a tragedy of “states’ rights” rather than a conflict over slavery. This movement built hundreds of monuments and influenced school curricula, shaping what generations of children were taught about the war and Reconstruction. Stone Mountain became one of the movement’s most ambitious dreams: a Confederate tribute so large it would dwarf ordinary dissent.

The Atlanta History Center’s research emphasizes how tightly the early carving effort was tied to the same cultural moment that re-legitimized the Klan and revived Confederate romanticism in popular culture—especially through D.W. Griffith’s film The Birth of a Nation, which helped popularize the image of the cross burning and rehabilitated the Klan as heroic vigilantes in the public imagination. The point is not merely that propaganda existed; it is that it supplied a visual language that extremist groups and “heritage” organizations could share.

Stone Mountain offered the perfect stage: a mountain already known locally, close to Atlanta, large enough to carry a myth of permanence. The dream of a massive Confederate memorial did not simply honor the past; it promised to anchor the future—to set the terms by which the South, and the nation, would remember.

1915: The Summit and the Spark

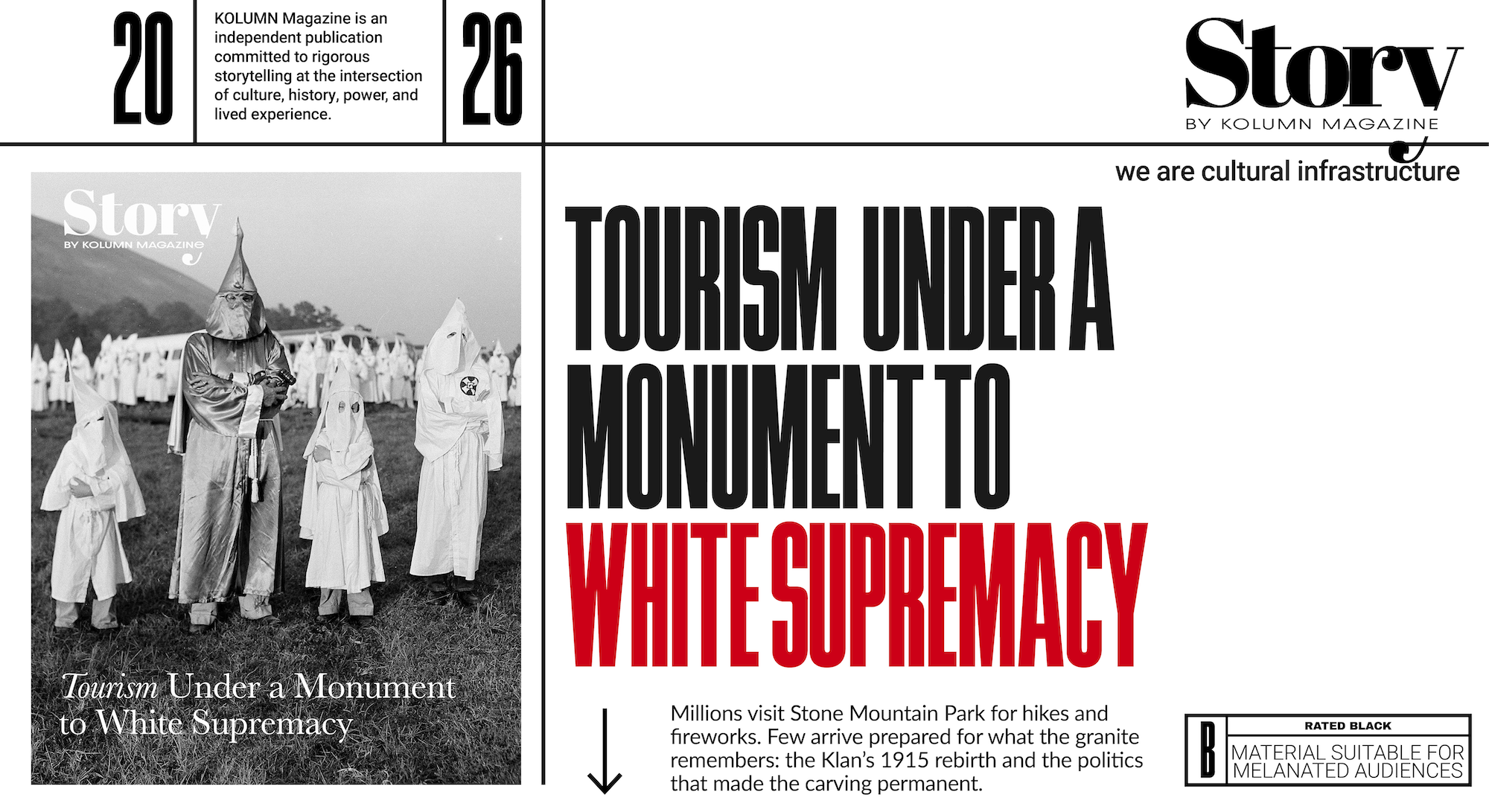

Stone Mountain’s link to the Ku Klux Klan is not a rumor or a metaphor. The second Ku Klux Klan—the twentieth-century organization that spread nationally, recruited millions at its peak, and made white supremacy into mass politics—was inaugurated with a cross burning on Stone Mountain in November 1915.

That 1915 ceremony has become a kind of origin story, repeated in historical accounts and in the Klan’s own mythology. It matters not because it was the first racist act in Georgia, but because it fused white supremacist ritual with a landscape that could be publicly accessed and publicly mythologized. A mountain is not a back alley. A mountain is a declaration: we are above you; we are visible; we will be remembered.

In the years that followed, the Klan used spectacle and ceremony to build momentum—parades, rallies, and pageants that framed the organization as a moral and patriotic force rather than what it was: a terror movement built on intimidation and violence. Georgia’s own historical encyclopedia notes the Klan’s twentieth-century evolution as a secret society devoted to white supremacy, existing in different forms across American history, with the 1915 revival serving as the hinge between Reconstruction-era violence and a national political machine.

Stone Mountain, in that context, functioned as a ritual site. The symbolism of “rebirth” on a summit, in firelight, had the kind of theatrical potency that movements rely on. And movements do not merely recruit with pamphlets; they recruit with belonging, with emotion, with the sensation of standing inside history.

The Venable Family, Easements, and a Home Base

The Klan’s relationship to Stone Mountain was also enabled by property and permission. Historical accounts note that members of the Venable family—who owned land around the mountain—were connected to the Klan’s early twentieth-century presence there, and that the Klan gained rights to use portions of the property. These arrangements mattered because they formalized the Klan’s ability to return, to host gatherings, to treat the mountain as a kind of institutional home.

One reason extremist groups endure is that they build logistical capacity—meeting spaces, sympathetic officials, fundraising networks. Stone Mountain offered not only symbolism but infrastructure. Over time, it became a recurring rally site. The mountain’s association with Klan ceremonies was widely understood enough that modern journalism and public history projects continue to cite it as foundational to the Klan’s revival.

The Carving’s Long, Uneven March

If Stone Mountain’s Klan story begins sharply in 1915, the carving story unfolds like an argument that keeps being postponed and then resumed with renewed force.

Early carving efforts involved prominent sculptors and major fundraising ambitions. The project became entangled in personality conflicts, money disputes, and competing visions of what the monument should represent. Public history accounts describe how the first phase of carving was partially completed, then later blasted away, then redesigned, with long pauses in between. The delays were not merely technical. They reflected the reality that even in the South, monumentalization required sustained political and financial will.

Yet the larger arc is unmistakable: the idea never died because it served a purpose. As the Smithsonian has reported, the monument’s meaning was not limited to commemoration; the park’s features and interpretive choices often presented sanitized versions of the antebellum South, minimizing slavery and reframing Confederate leaders as romantic figures.

Stone Mountain’s advocates tended to describe the project as heritage. Its critics described it as propaganda. Both sides recognized the same truth: a mountain-size image is not neutral.

Massive Resistance and the State’s Hand

The most consequential shift came in the mid-twentieth century, when the state of Georgia stepped in and turned Stone Mountain into an explicit public project.

After Brown v. Board of Education (1954), white Southern political leadership faced a legitimacy crisis. Desegregation threatened the racial order that had been enforced through Jim Crow law and violence. Across the South, the backlash took many forms—school closures, “interposition” rhetoric, the rise of Citizens’ Councils, and renewed Klan activity. Stone Mountain’s memorial project reemerged in that climate.

Public history summaries and encyclopedic accounts describe how the state purchased the mountain and surrounding land in 1958, and how the Georgia legislature created the Stone Mountain Memorial Association (SMMA) to manage the site as both memorial and recreation destination. The timing is central to the story: the memorial was not simply preserved from an older era. It was actively revived and accelerated as the civil rights movement was reshaping the nation.

The Atlantic has argued that Confederate monuments are best understood not as ancient relics but as political artifacts created to send messages in particular eras—often the era of Jim Crow and the era of massive resistance. Its treatment of Stone Mountain follows that pattern, noting how the project was revitalized in the wake of desegregation battles and later protected by state law.

Stone Mountain is a case study in how a state can use commemoration to signal defiance. Funding, governance, and legal protections transformed a private dream into a public obligation.

Klan Spectacle in the Mid-Century South

Even as the state turned Stone Mountain into a memorial park, the Klan remained part of the mountain’s lived history. Accounts describe cross burnings and rallies at or around the site across decades, with Klan events drawing crowds and attention.

This dual-track reality—state-sponsored Confederate memorialization alongside Klan ritual—helps explain why many Black Georgians and civil rights advocates have long treated Stone Mountain as more than an offensive sculpture. It is a symbol of coordinated systems: formal power and informal terror, operating in the same ecosystem.

In 1962, a confrontation over Klan activity on the mountain underscored how politically volatile the site had become, with state authorities attempting to manage demonstrations and prevent violence. The details matter less than the broader point: by the mid-twentieth century, Stone Mountain was widely recognized as a flashpoint, a place where white supremacy was not merely remembered but performed.

1965, 1970, 1972: A Dedication in the Civil Rights Era

Stone Mountain Park officially opened in 1965—an anniversary-laden moment that critics have noted as symbolically charged. The carving itself moved toward completion in the late 1960s and early 1970s, with dedications and ceremonies that effectively crowned the project during and after the peak years of civil rights agitation.

This timing is the central irony of Stone Mountain: the nation was dismantling legal segregation, and Georgia was finalizing the largest Confederate monument in the country.

The project’s defenders could argue they were finishing what earlier generations started. But history is not only about beginnings; it is about why a society chooses to continue. The renewed push to complete the carving was not a neutral act. It was a public statement about whose story would be elevated—literally elevated on a mountainside—during a period when Black citizens were demanding full inclusion.

A Park of Leisure Built Around a Political Image

Over time, Stone Mountain Park developed into a major tourist attraction, marketed for recreation as much as commemoration. Millions visit, drawn by trails, family attractions, and seasonal programming. For decades, the park’s laser show projected imagery onto the mountain, weaving entertainment with the carved Confederate narrative—a choice that became increasingly controversial as national debates over monuments intensified.

This is where Stone Mountain’s “normalization” power becomes clearest. When a monument sits behind ticket booths and snack stands, it can fade into the background of family memory. Children remember the train ride and the fireworks. Parents remember the picnic. The carving becomes scenery—until someone insists it is not.

Critics have long argued that this is precisely the danger. A monument built to sanctify white supremacy becomes easiest to maintain when it is treated as mere backdrop.

The Legal Locks: Protection by Statute and Structure

Stone Mountain’s persistence is not only cultural. It is legal.

Georgia law has been widely understood to constrain removal or alteration of protected monuments, and Stone Mountain has additional statutory protections tied to its status as a memorial. Those legal locks matter because they limit what state officials can do even if political will changes. They also create a predictable pattern: reform efforts are channeled toward “context” and interpretation—museum exhibits, signage, flag placement, programming—rather than physical change to the carving itself.

This legal reality shapes today’s battles. When opponents of reform claim that any reframing violates the park’s purpose, they are often making a legal argument as well as a cultural one. And when reformers call for new exhibits and historical truth-telling, they are sometimes choosing the only tools the law leaves available.

The New Front: Context, Redesign, and Lawsuits

In the past several years, Stone Mountain has become a test case for a broader national shift: the move from arguing only about removal to arguing about public narrative.

According to reporting by The Associated Press, the Stone Mountain Memorial Association voted to begin changes that include relocating Confederate flags and altering the park’s branding, and the state allocated substantial funds for a redesigned exhibit intended to address the park’s links to slavery, segregation, the Klan, and the Lost Cause. That effort has triggered legal challenges from Confederate heritage groups, who argue that the proposed interpretation violates state requirements to preserve the memorial character of the site. Reuters likewise describes the conflict as a battle over whether the museum redesign can explicitly foreground slavery and racism while the carving remains untouched, noting state funding and the push for a more comprehensive narrative.

Black press and advocacy voices have framed these developments as overdue, not radical. Word In Black, covering organizing efforts around the site, has described Stone Mountain as a place where activists seek to confront a public narrative that still elevates Confederate leaders without sufficient context. The Root has also reported on the legal and political efforts to resist exhibits that link the park to slavery, segregation, and the Klan, underscoring how the fight now includes not only stone and flags but also what visitors are permitted to learn.

In that sense, Stone Mountain’s current struggle is not only about memory. It is about governance: who controls the story a state tells about itself, and whether public institutions can describe white supremacy plainly without being accused of “politics.”

The Moral Problem of “Both Sides”

Journalistic fairness does not require false equivalence. Stone Mountain’s defenders often use language of heritage, ancestry, and regional pride. Those sentiments can be sincerely held. But sincerity does not neutralize historical meaning.

The Confederate leaders depicted on Stone Mountain fought for a government explicitly formed to preserve slavery. The Klan revived at the mountain was an organization built to enforce racial hierarchy through intimidation and violence. The overlap between the two stories is not incidental; it is structural. At Stone Mountain, Confederate romanticism and Klan resurgence were not separate chapters in distant centuries. They were parts of the same twentieth-century project to preserve white supremacy in new forms.

This is why so many critics argue that incremental changes—moving flags, revising brochures, adding exhibits—can feel like managerial fixes applied to a foundational wound. Yet those incremental changes are also where power often shifts. It is easier to keep a monument’s meaning stable when the museum beside it refuses to tell the full story.

The Community Around the Mountain

Stone Mountain is not an empty symbol. It sits amid real neighborhoods, and those neighborhoods have changed. Metro Atlanta’s demographic evolution means the park’s visitors include families for whom the carving is not heritage but hostility.

That tension has created moments of public confrontation and re-occupation. In 2020, for example, the national monument debate prompted protests and public actions at Stone Mountain, including demonstrations calling for removal or radical recontextualization. These actions were not only symbolic; they asserted a competing claim: that the mountain, as public land, belongs to everyone, and therefore must answer to everyone.

This is one of Stone Mountain’s under-discussed truths: monuments do not only impose meaning; they provoke counter-meaning. Every plaque or exhibit is a negotiation between power and protest.

What an Honest Stone Mountain Might Require

The most common public question is whether Stone Mountain can be “redeemed.” The Washington Post has framed the dilemma explicitly: can a Confederate monument be reinterpreted in a way that serves public truth, or does it remain irredeemably tied to white supremacist origins? The Guardian has published both reported features and opinion arguments that wrestle with options ranging from removal to landscape redesign to deliberate obscuring—efforts to undermine the monument’s triumphal presentation even if it cannot legally be demolished.

The answer depends, in part, on what one means by “redeem.” If redemption means making the monument harmless, that may be impossible. A carving at that scale is designed to dominate. If redemption means making the site educational rather than celebratory, that is more plausible, but it requires an institutional willingness to say plainly what the monument is and why it was built when it was built.

Smithsonian’s reporting underscores how interpretive choices—like presenting plantation life as quaint or describing enslaved people in euphemisms—can launder history rather than confront it. A truthful Stone Mountain would reverse that logic. It would make the carved image the beginning of the conversation, not the end. It would foreground the Klan’s use of the site, the state’s role in completing the carving during desegregation backlash, and the ways public memory has been engineered to soothe rather than to clarify.

It would also treat the surrounding Black communities not as footnotes but as central to the site’s story: the people who lived under the monument’s shadow, who navigated a region shaped by both economic growth and racial intimidation, who watched Georgia celebrate Confederate leaders during the same decades those communities were fighting for basic civil rights and safety.

The Question Stone Mountain Forces on the Country

Stone Mountain is often discussed as a Georgia problem. It is not.

It is an American problem in granite. It asks whether the country can hold two ideas at once: that public land can host family leisure, and that the same land can carry a monument erected to enshrine an anti-democratic, pro-slavery cause—while also serving as a historical stage for the Klan’s modern revival.

The mountain also exposes the limits of the “time heals” argument. Time has not neutralized Stone Mountain. Time has, in some ways, made it more powerful, because each generation inherits the monument already installed, already normalized, already folded into the state’s tourist economy. The monument survives not only because people defend it, but because it is expensive and difficult to confront, and because law can fossilize politics.

If Georgia’s current museum redesign efforts succeed, they may provide a model for other places where removal is politically or legally constrained: telling the truth as an act of public repair. If they fail—if lawsuits and legislative restrictions succeed in limiting what can be said—Stone Mountain will remain what it has long been: a public park where the state subsidizes a selective past.

Either way, the mountain will keep forcing the same question. Not what we remember, but who gets to decide what remembrance looks like, and what price the rest of the public pays for that decision.