KOLUMN Magazine

What forms of solidarity, policy, and resistance are possible when the country’s history suggests that gains will be challenged, narrowed, and re-coded?

What forms of solidarity, policy, and resistance are possible when the country’s history suggests that gains will be challenged, narrowed, and re-coded?

By KOLUMN Magazine

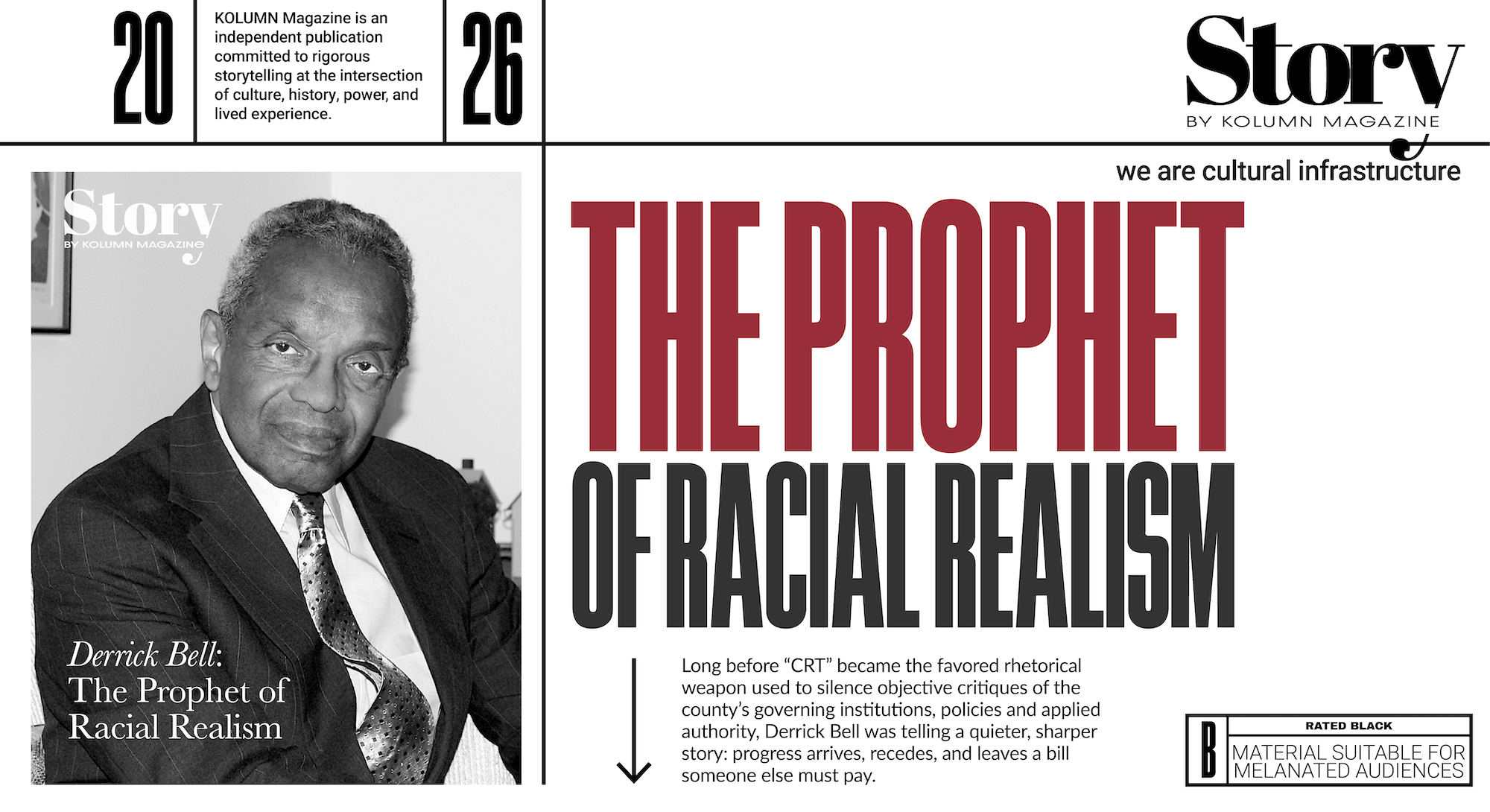

On a crisp day in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the scene looked like the familiar choreography of an American institution confronted by its own reflection: microphones clustered, students packed close, signs lifted at shoulder height, the air of a campus protest charged by the belief that arguments—if well made, if morally coherent—might bend a powerful place toward change. Derrick Bell stood at the center of it, a law professor whose manner was often described as soft-spoken, even gentle, and whose choices had repeatedly forced his colleagues, his students, and the legal profession to answer an uncomfortable question: what does it mean to claim fidelity to equality while accepting the routines that keep inequality stable?

Bell had already made history at Harvard Law School as its first tenured Black professor. He had also, by the early 1990s, given Harvard an ultimatum that was not negotiable and not performative: he would not teach there again until the school hired a Black woman for its faculty. Harvard did not meet that demand on his timetable. Bell’s protest became the kind of story elite institutions rarely enjoy—one in which the dissenter’s credibility grows because he proves he will pay for principle. Harvard’s own tribute to Bell later described how he gave up his professorship in protest over the lack of women of color on the faculty.

That stand is often recalled as a footnote in the culture-war retelling of “critical race theory,” a term that has been flattened into a partisan insult. But in Bell’s life and work, the protest was not a detour from scholarship. It was scholarship acted out in public. His writing had long insisted that American institutions—courts, legislatures, universities—rarely change out of moral awakening alone. They change when incentives shift, when reputational risk rises, when power calculates that concession is cheaper than resistance. In Bell’s vocabulary, that is “interest convergence,” a concept he developed in legal scholarship and that later became one of the best-known analytic tools associated with critical race theory.

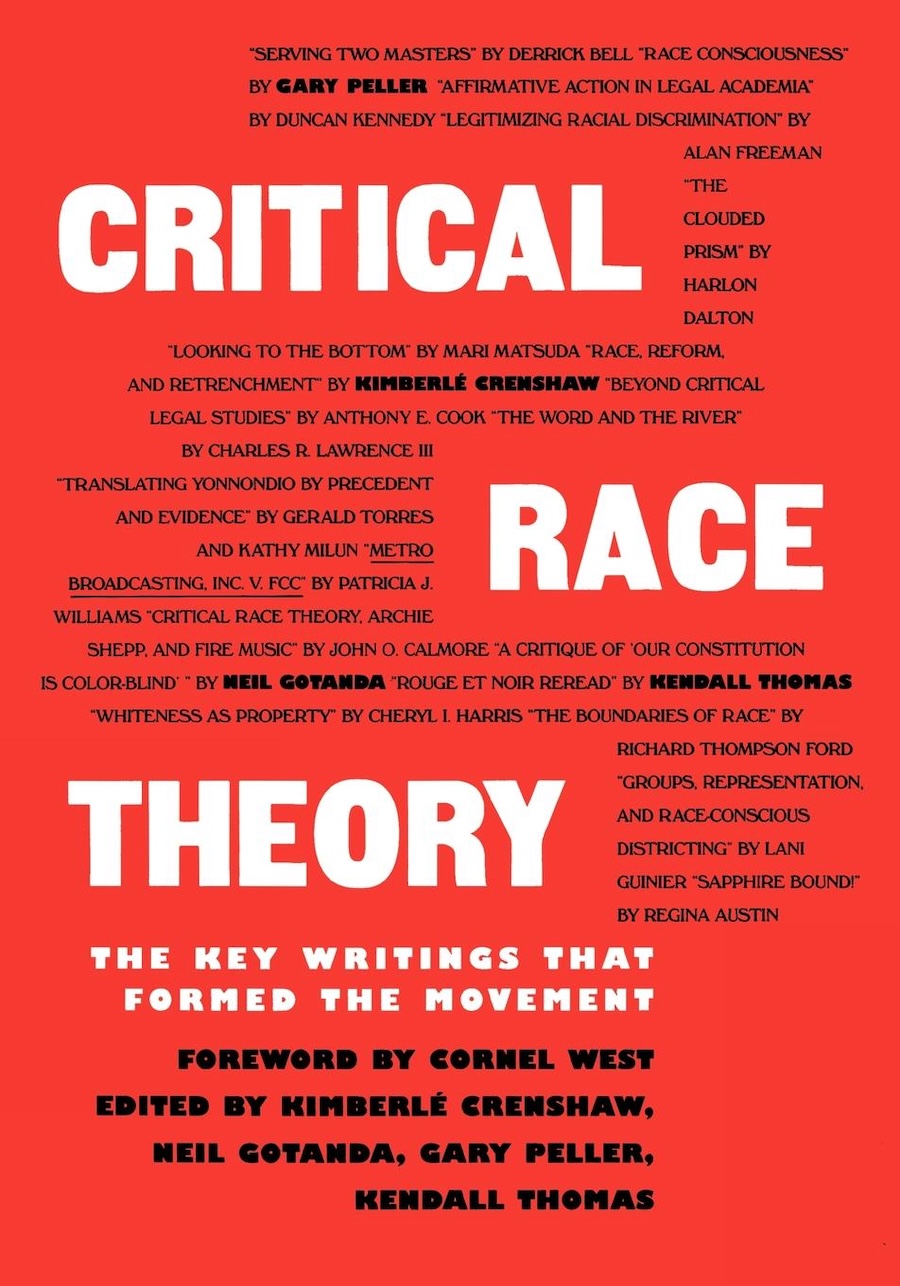

If Bell’s name now circulates widely, it is often without the texture that made him both admired and contested: he was not merely diagnosing racism as a personal failing or an ideological error, but as a durable arrangement embedded in American law and political economy. In perhaps his most famous book, Faces at the Bottom of the Well: The Permanence of Racism, published in 1992, he did something that unsettled even sympathetic readers. He argued that racism is permanent—not because Americans are incapable of decency, but because the country’s structures repeatedly regenerate racial hierarchy, adapting to new norms while preserving old outcomes. He delivered that thesis not as a single, linear treatise, but through a hybrid form: legal analysis braided with allegory, parable, and speculative storytelling.

The result is a book that continues to operate on two levels at once. It is, on the surface, a set of unsettling stories: courtroom scenes, policy proposals, surreal bargains, futures that feel exaggerated until they begin to resemble the news. Underneath, it is a cold assessment of the post–civil rights era—an era that wanted to believe the major battles had been won, even as schools resegregated, wealth gaps widened, and criminal punishment hardened. Bell’s insistence was that the country’s narrative of steady racial progress was itself a kind of anesthesia. The book’s task was to wake the reader up, even at the cost of hope.

To read Bell well now requires more than repeating his most quoted lines or treating his “permanence” claim as a dare. It requires understanding how he arrived there: as a lawyer in the trenches of desegregation litigation, as a professor who watched elite legal education reproduce elite legal instincts, and as a writer who believed that conventional argument had become too easy to ignore. Bell’s great provocation was not simply that racism endures. It was that the stories Americans tell themselves about racism—stories of linear improvement, heroic rulings, inevitable integration—can become part of the mechanism that keeps racism functional.

From civil-rights lawyer to institutional heretic

Bell’s biography reads, at first glance, like a classic arc of American merit and achievement. Born in Pittsburgh in 1930, he served in the U.S. Air Force and eventually became a lawyer who worked within the civil-rights legal apparatus shaped by Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. He joined Harvard Law School’s faculty in 1969 and became its first tenured Black professor in 1971, an institutional milestone that carried both symbolic weight and practical isolation.

Yet Bell’s life is best understood not as a climb into the establishment but as a series of collisions with it. The legal establishment wanted certain kinds of civil-rights stories—ones where the Supreme Court speaks, the nation listens, justice advances. Bell had lived long enough inside litigation to see how often that narrative failed on the ground. The New Yorker’s portrait of Bell traces one of the formative experiences: his work on school desegregation in Mississippi, where the practical realities of “integration” could clash with the actual interests and safety of Black communities.

This was not a repudiation of Brown v. Board of Education as a moral landmark. It was a skepticism about what landmark rulings reliably deliver once they meet local power. Bell’s later writing returned again and again to the gap between doctrine and implementation, between a courtroom victory and a community’s lived conditions. In a Harvard Law Review reflection on Bell’s work, the author describes Bell’s insistence that the struggle against racism must be persistent precisely because racism is adaptive.

Bell’s protest at Harvard over the absence of women of color on the faculty was, in this sense, not merely about representation. It was about how knowledge is produced. If legal education is one of the engines that generates judges, prosecutors, corporate lawyers, policymakers—then the boundaries of what counts as “serious” scholarship and “qualified” expertise become political facts. Harvard’s own account of Bell emphasized that his protest drew national attention and stirred intense student passions. That is an institutional way of saying: he made it impossible to treat the issue as a quiet internal matter.

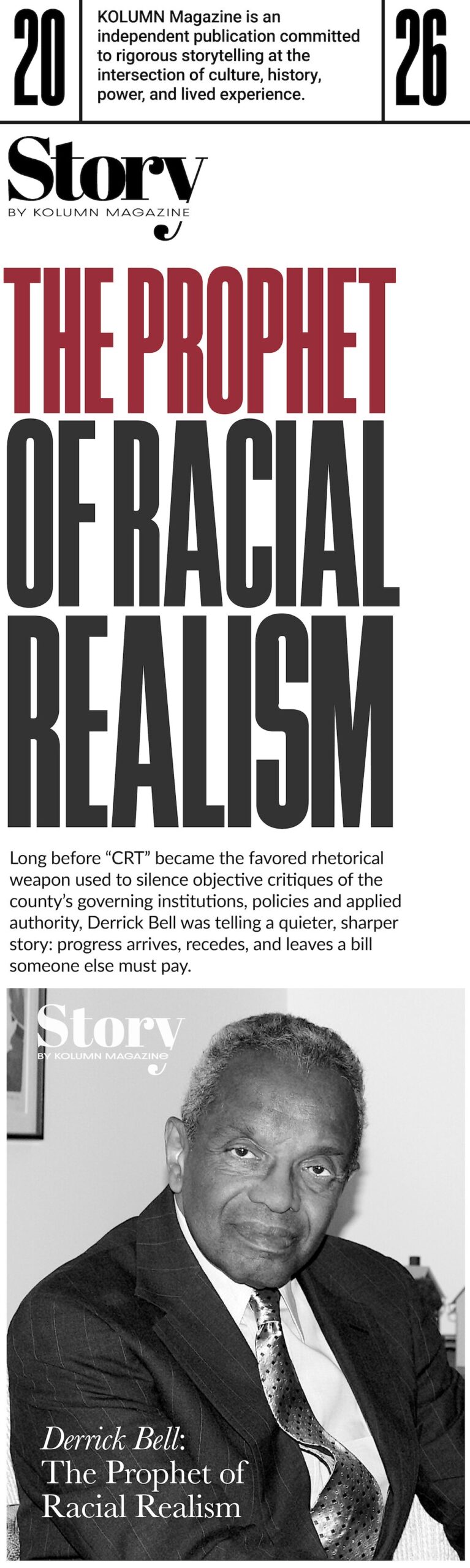

In today’s shorthand, Bell is frequently called a “founder” or “godfather” of critical race theory, a label that is partly accurate and partly reductive. The intellectual movement that came to be known as CRT developed through multiple scholars and controversies, including student activism and “alternative courses” at Harvard. Bell mattered not because he coined every term, but because he insisted on a premise that many legal liberals found impolite: that equality rhetoric can coexist with inequality outcomes for a very long time, and that courts often stabilize the system they are asked to reform.

In other words, Bell treated racism not as an error in the machine but as part of the machine’s operating system.

Why Faces at the Bottom of the Well still lands like a punch

Published in 1992, Faces at the Bottom of the Well arrived at a particular American moment: the civil-rights consensus was fraying, conservative jurisprudence was ascendant, and public discourse was beginning to shift from rights to resentment. Bell’s book refused the era’s comforting binaries. It did not say “progress is impossible” in order to justify cynicism. It said progress is often temporary in order to demand clearer-eyed strategy.

The Washington Post’s contemporary review captured Bell’s core metaphor and its social function: Black Americans as the “faces at the bottom of the well,” whose low status reassures whites of their relative position, binding white society through an unspoken agreement that hierarchy will be maintained. The image is not subtle. It is not designed to be. The well is a structure: deep, narrow, difficult to escape, and useful precisely because it organizes visibility. The people at the top look down, confirm their elevation, and call it normal.

Bell’s argument about permanence is often misheard as fatalism. In fact, the book’s architecture suggests something else. Bell writes through a dialogue with Geneva Crenshaw, a fictional Black woman lawyer who challenges, interrogates, and occasionally scolds the narrator. Scholars have noted how Geneva functions as a conscience and a critic inside Bell’s own text—an interlocutor who forces the argument to earn its bleakness and to clarify its ethical demands.

That device matters. Bell is not simply delivering pronouncements; he is staging a debate about how Black Americans, and their allies, should understand the terrain. Geneva is there to ask what any reader might ask: if racism is permanent, what is the point of struggle? Bell’s answer, across the book, is not resignation but “racial realism,” a posture that rejects illusions of inevitable progress while still insisting on resistance as a moral and practical necessity. That framing—realism rather than despair—helps explain why Bell’s work has remained influential in legal academia even when it has been politically caricatured.

The method: Allegory as jurisprudence

One of the reasons Faces continues to provoke is that it is not written in the expected voice of legal scholarship. Bell uses speculative narratives as a way to strip away polite excuses. If readers can always say, “That’s not how the world works,” Bell responds by inventing a world where the underlying logic is made explicit.

The most famous example is “The Space Traders,” a story that imagines white America offered a bargain by extraterrestrials: in exchange for prosperity and environmental repair, the United States would hand over its Black citizens. The scenario is grotesque. It is also, in Bell’s hands, a test of national ethics and political calculation. The point is not to predict literal aliens; it is to dramatize how quickly a society will rationalize sacrifice when the sacrificed have been positioned as disposable.

The Washington Post, discussing Bell’s work a few years later, summarized the parable in blunt terms: in Bell’s imagined world, white Americans sell off Black Americans to space aliens. The outrage this story generated—especially among critics who dismissed it as “macabre science fiction”—is part of Bell’s strategy. He is asking: what level of horror must be introduced before the ordinary horror becomes visible?

This is also why Faces is frequently taught beyond law schools. Allegory allows Bell to do what doctrinal analysis sometimes cannot: to make moral tradeoffs explicit. Legal arguments can hide behind neutrality, behind standards and tests and procedural posture. Stories have fewer hiding places. A story forces the reader to inhabit the logic rather than admire the rhetoric.

Bell’s C-SPAN appearance in 1992, discussing the book, underscores that he understood the book as a public-facing intervention, not just an academic exercise. He was building a bridge between legal theory and civic argument—between the internal debates of elite institutions and the lived realities of discrimination.

The thesis that still enrages: Permanence

Bell’s permanence claim is, in part, descriptive. He surveys American history and sees racial hierarchy mutating rather than disappearing. When one legal regime becomes discredited, another emerges: slavery to Black Codes to Jim Crow to nominally colorblind systems that preserve stratified outcomes. When overt language becomes unacceptable, new language takes its place.

But permanence is also, in Bell’s writing, an interpretation of political behavior. He insists that white majorities have repeatedly accepted racial reforms only when those reforms align with white interests—economic, geopolitical, reputational. This is where “interest convergence” becomes not just a theory but a warning. If reforms depend on convergence, then reforms will be fragile. When interests diverge, progress can be reversed, narrowed, or redefined.

The Washington Post’s obituary of Bell, written when he died in 2011, quoted his blunt formulation from Faces: “Black people will never gain full equality in this country.” It is a sentence that can sound like surrender if pulled from context. In the book, it functions more like a demand: stop confusing legal recognition with material transformation; stop treating temporary peaks as permanent victories; stop letting the rhetoric of equality substitute for the work of power.

In another Washington Post column that referenced Bell’s book, the writer quoted his claim that even “herculean efforts” hailed as successful can produce only “temporary peaks of progress,” short-lived victories that slide into irrelevance as racial patterns adapt to maintain dominance. The language is designed to sting because it contradicts the civic religion of gradual improvement.

Bell knew that his claim would be rejected by many Americans on instinct. He also knew that civil-rights lawyers, trained to argue for victories, might treat permanence as strategically self-defeating. That tension is built into Faces. The book is, among other things, an argument with liberal legalism—the belief that the right court decision, the right statute, the right principle, will steadily straighten the arc.

Bell does not deny the importance of legal wins. He denies the mythology that legal wins are self-executing.

Reading the book as a series of tests

A helpful way to read Faces is to treat each chapter as a stress test of a particular American belief.

One belief is that racial injustice is primarily the product of ignorance or malice, and that exposure or education will fix it. Bell’s stories suggest that even when racism is acknowledged, institutions can incorporate that acknowledgment without altering underlying distributions of power. In other words, awareness can become a performance: the system learns the right language and continues.

Another belief is that Black advancement is a straightforward moral good for the nation. Bell repeatedly forces the reader to consider how Black progress is tolerated, or even celebrated, when it is useful—when it can be framed as proof of national virtue, when it stabilizes social order, when it serves economic needs. The “faces at the bottom” metaphor is not simply about cruelty; it is about function. Hierarchy, Bell argues, gives certain groups psychological wages and political cohesion.

A third belief is that integration, as a remedy, is always aligned with Black interests. Bell’s earlier scholarship, and the biography traced by The New Yorker, shows how his experience in desegregation cases led him to question whether the pursuit of racial balance sometimes conflicted with client interests and community stability. This is not an argument against contact or shared institutions in principle. It is a warning that remedies chosen for symbolic appeal can ignore the preferences and needs of the people they claim to serve.

Bell is often portrayed as a pessimist because he refuses to guarantee that the system can be redeemed. But Faces is more precise than that. Bell is pessimistic about the system’s incentives, not about people’s capacity for courage. He is skeptical about “inevitable progress,” not about the possibility of meaningful struggle.

This distinction matters because it shifts the question from “Will America become just?” to “What do we do in a country that can become less unjust without becoming just?”

The critics: Where Bell is most vulnerable

A serious review of Faces has to attend to the arguments against it, especially because Bell’s own method invites dispute. He does not merely present data; he presents a worldview.

One scholarly critique, published in the mid-1990s, framed Bell’s thesis as a direct challenge to deeply held civil-rights ideals and questioned whether his permanence claim risks foreclosing the very coalitions and commitments that make progress possible. The worry is not trivial: if readers accept permanence as destiny, they may treat resistance as theater rather than strategy.

There is also the critique, voiced by other prominent legal scholars, that Bell’s stories sometimes substitute moral shock for analytic clarity. Parables can reveal, but they can also oversimplify, turning complex social dynamics into a single mechanism. Bell’s defenders might reply that the oversimplification is intentional: a parable is a lens, not a census. Still, the concern stands—especially in a policy environment where opponents of racial reform are eager to label any structural analysis as conspiracy.

Another line of criticism targets Bell’s rhetorical posture. A Washington Post opinion column in 1992 described a critique by Randall Kennedy—Bell’s Harvard colleague—faulting Bell for explaining but not condemning certain bigotries in the political landscape, suggesting an “egregious toleration of bigotry.” The underlying issue is whether Bell’s insistence on structural analysis sometimes leads him to treat ideological actors as symptoms rather than moral agents.

Kennedy’s later writing on Bell is more expansive and personal, reflecting on Bell’s influence and the challenge Bell posed to the liberal legal imagination. The fact that Bell generated both admiration and sharp critique within elite Black intellectual circles is itself evidence of his significance. He was not simply preaching to the choir. He was arguing with the choir about what song they should be singing.

A further critique is practical: if racism is permanent, what is the program? Bell’s work can read as diagnostic more than prescriptive. In response, Bell often suggested a shift in goals—from the dream of full equality as an endpoint to the pursuit of concrete improvements, protections, and strategies that reduce harm and expand agency even in a hostile system. The Harvard Law Review reflection on Bell emphasizes that he urged persistence and realism as a form of resistance. But critics may still find this too indeterminate, too reliant on moral stamina rather than institutional design.

These are real vulnerabilities. They also help explain why Faces remains a live text: it is not merely a period piece of early-1990s legal theory; it is an argument about how to interpret every subsequent decade.

The defenders: What Bell gets right with unnerving consistency

If the critics worry Bell makes hope harder, the defenders argue that Bell makes false hope harder—and that this is a moral service.

One reason Faces continues to resonate is that many of its claims have aged into plausibility. The idea that civil-rights victories can be narrowed by subsequent courts; that reforms can be recoded as “neutral” while producing racialized outcomes; that institutions can celebrate diversity while preserving hierarchy—these are now common observations across disciplines. Bell did not invent the reality; he sharpened the language to describe it.

The New Yorker’s account of Bell’s legacy emphasizes how his ideas—interest convergence, the permanence of racism—were forged through disillusionment with the legal system’s ability to deliver substantive racial justice, and how they later became foundational to CRT. This is an important corrective to the caricature of CRT as mere ideological indoctrination. Bell’s work emerged from legal practice and institutional observation, not from abstract grievance.

The continued citation of Bell in mainstream commentary also illustrates his conceptual reach. The Guardian, in a 2021 piece explaining the moral panic around CRT, described CRT as an analytic framework developed by law professors including Bell to discern how racial disparities are reproduced by law and persist even after discriminatory policies are revised. This is closer to Bell’s own self-understanding: he was trying to explain how a society can outlaw discrimination and still sustain racial inequality.

Even in contexts far from legal scholarship, Bell’s metaphors have traveled. The Guardian has quoted Bell’s “faces at the bottom of the well” imagery in reviewing contemporary books about racist America, demonstrating how his language has become a portable way to describe racial hierarchy’s psychological and social function.

Bell’s defenders also point to something that is sometimes missed in the “permanence” debate: Bell was not urging passivity. He was demanding a more disciplined account of cause and effect. If progress is often conditional, then strategy must be built around conditions—not around moral narratives about who “should” do what.

Geneva Crenshaw and the ethics of arguing with yourself

One of the most quietly radical choices in Faces is Bell’s insistence on writing against himself. Geneva Crenshaw is not a side character; she is the structural mechanism that prevents the book from becoming a manifesto.

In legal scholarship, the author often presents as a stable voice—confident, authoritative, in control. Bell introduces Geneva to destabilize that posture. She presses him on his assumptions, tests his conclusions, and forces the reader to sit inside unresolved tension. Scholars discussing Bell’s use of Geneva describe her as a constant challenger to Bell’s ideas about achieving racial justice through civil-rights law.

This is not merely stylistic. It is epistemological. Bell is suggesting that the correct stance toward racism is not certainty but disciplined confrontation with contradiction. If the system is adaptive, then any theory that claims to have solved it is suspect. Geneva keeps the book from granting the reader the comfort of closure.

In the politics of today—where slogans travel faster than arguments—this may be Bell’s most underappreciated legacy: the insistence that thinking about race requires internal argument, not just external accusation.

Bell’s relevance in the era of “CRT” as an epithet

Bell died in 2011, years before critical race theory became a staple of school-board debates and cable-news outrage. But the current backlash, in a perverse way, confirms one of Bell’s insights: that institutions and majorities will resist frameworks that threaten to make the system legible.

The New Yorker’s writing on CRT’s origins describes how Bell’s presence at Harvard and student activism around race and the law helped fill a void in legal education, producing an intellectual movement that was never primarily about personal guilt but about structural critique. The Guardian’s commentary has likewise stressed that “real CRT” is an academic framework, not the caricature of divisiveness deployed in political campaigns.

Bell’s work is therefore relevant not simply because it is cited in CRT debates, but because it explains why those debates are so combustible. A society that prefers to treat racism as an aberration will react defensively to any theory that treats it as structural. Bell anticipated that defensiveness. He built it into his analysis. The backlash becomes, in Bell’s terms, a predictable adaptation.

And yet Bell’s own life complicates any attempt to reduce him to an icon of radical critique. He worked inside the state; he litigated; he taught at elite institutions; he wrote casebooks. He was not calling for withdrawal from the law. He was calling for honesty about what the law can and cannot do.

What a deep reread demands from the reader

A deep reread of Faces at the Bottom of the Well is unsettling in part because it refuses the reader a comfortable role. Many books about racism offer a path to virtue: learn the history, acknowledge the harm, adopt better attitudes, support better policies. Bell does not reject those steps, but he doubts they are sufficient. He is asking for something more demanding: an acceptance that the system may not be designed to reward virtue, and that moral clarity does not guarantee political victory.

This is where Bell’s Harvard protest and his writing converge. The protest was not merely symbolic; it was a wager that the institution would face pressure it could not ignore. Harvard did not meet his demand quickly, and Bell paid with his position. The lesson is not that protest always works. The lesson is that protest exposes the institution’s true priorities.

The same is true of Faces. Bell uses stories as leverage, trying to force the reader to admit what their preferred narrative excludes. If the reader rejects his conclusions, they must still grapple with his evidence: the recurrence of racial hierarchy across centuries, the conditional nature of reforms, the speed with which the country tires of racial reckoning.

Bell’s claim of permanence is not a prophecy to be admired or mocked. It is a challenge to strategy. If he is wrong, the reader should be able to show how—by identifying mechanisms that produce durable, not temporary, transformation. If he is right, the reader must decide what kind of politics is possible without the promise of an end state called “racial equality.”

This is what Bell meant by realism: not despair, but the refusal to lie to yourself about the terrain.

The book’s enduring power: Clarity without consolation

Nearly every generation produces writers who tell America what it wants to hear about itself, and writers who tell America what it does not. Bell belongs firmly in the second category. He is also, crucially, not writing from outside the tradition of American legal ideals. He is writing from inside them—using their language, their cases, their institutions—while insisting that ideals are not the same as outcomes.

The Washington Post’s 1992 review of Faces framed Bell’s argument as an account of a white society bound by an unspoken pact to keep Black Americans at the bottom, a ranking embedded in culture and stabilizing across history. That is not the language of incrementalism. It is the language of structure. It is why Bell remains so difficult to domesticate.

And yet Bell’s influence is not merely rhetorical. It is methodological. He taught scholars to ask what incentives drive racial reforms. He taught activists to distrust symbolic victories without enforcement. He taught students to treat law not as a neutral arbiter but as a site of contest, saturated with history.

When Bell is reduced to a single sentence—“racism is permanent”—the reduction misses the moral labor he is demanding. Bell is not asking the reader to give up. He is asking the reader to stop confusing hope with analysis. He is asking what forms of solidarity, policy, and resistance are possible when the country’s history suggests that gains will be challenged, narrowed, and re-coded.

In that sense, Faces at the Bottom of the Well is not simply a book about racism. It is a book about time: about cycles, backlash, forgetting, and the repeated effort required to keep any victory from becoming a brief peak before the slide. It is a book that refuses the American preference for happy endings—and insists, instead, on the harder dignity of struggle without guarantees.

Bell’s legacy, then, is not a mood. It is a discipline.