A throughline is labor: the daily, strategic work of maintaining a husband’s legacy while ensuring children were fed, educated, protected, and allowed to become themselves rather than living monuments.

A throughline is labor: the daily, strategic work of maintaining a husband’s legacy while ensuring children were fed, educated, protected, and allowed to become themselves rather than living monuments.

By KOLUMN Magazine

There is a particular quiet that arrives after the shouting stops. It is not peace. It is the moment a body recognizes that the worst thing has already happened—and that the world has not paused to accommodate it.

In June 1963, that quiet settled over a driveway in Jackson, Mississippi, where a civil rights field secretary was murdered and a young family’s sense of safety was shattered along with the screen door. In February 1965, it poured into a Manhattan ballroom as a pregnant mother watched her husband fall in front of an audience. In April 1968, it moved through a motel corridor in Memphis and then across the country, where grief erupted into riots and legislation and speeches that attempted, almost desperately, to make meaning out of catastrophe.

The United States remembers the men: Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr. The nation’s calendar, courthouse transcripts, documentaries, and commemorations are built around their names. But history, like a household, does not run on names alone. It runs on the people who do the work after the funeral—the people who raise children who wake up hungry the next morning; who answer the phone; who decide whether to leave the porch light on; who figure out what it means to keep a legacy from turning into a slogan.

Coretta Scott King, Myrlie Evers-Williams, and Betty Shabazz became widows in the most public way possible. Their grief was witnessed, photographed, interpreted, and weaponized. Each woman inherited a legacy that America wanted to claim, sanitize, and selectively quote. Each woman also inherited something more ordinary and, in practice, more demanding: a household of children whose lives had just been split into a before and an after.

The throughline of their journeys is not simply resilience—though the word appears often in tributes, as if it is the only acceptable reaction to loss. The throughline is labor: the daily, strategic work of maintaining a husband’s legacy while ensuring children were fed, educated, protected, and allowed to become themselves rather than living monuments. Their lives are not addendums to martyrdom. They are case studies in what it costs to carry history when history has just burned through your front door.

A private catastrophe becomes public property

Assassination has two victims: the person killed and the people forced to live in the crater.

When Medgar Evers was murdered in 1963, his widow, Myrlie, was 30 years old. Their children were young. The murder was not merely a political act—it was an intimate violation, staged at home, where families are supposed to be safest. Decades later, the National Park Service would describe the “long-delayed justice” that followed: two trials in 1964 ended without a conviction; only in 1994 would a jury finally convict Byron De La Beckwith and sentence him to life in prison. The timeline is not just legal history. It is the measure of a mother’s endurance—the length of time a family lived with an unresolved ending.

When Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965, Betty Shabazz became the sole parent to six daughters—some still toddlers, and two not yet born. The Guardian, reflecting on biographical accounts, captured the blunt arithmetic: children who were six, four, two, and “a few months old,” with Shabazz pregnant with twins who would arrive months later. It is one thing to lose a partner. It is another to lose a partner while holding the future in your body, while cameras and politics and rumors swarm.

When Martin Luther King Jr. was killed in 1968, Coretta Scott King was 41, with four children who ranged from young adulthood to early childhood. Her husband’s assassination did not end the movement; it changed its center of gravity, shifting a portion of the struggle into institutions, holidays, archives, and the long contest over how a country remembers what it once feared.

All three women faced the same immediate problem: the nation wanted their grief, and it wanted it on schedule. There were speeches to make, funerals to organize, calls to return, causes to justify, enemies to fear, and children to explain things to—children whose questions would not arrive in the neat language of press statements. The public asked for grace. The private reality demanded logistics.

The public story often begins with composure: the widow who stands tall, who does not crumble, who speaks with clarity. But the more honest beginning is confusion. Who pays the bills? Who decides where the children go to school? Who determines whether a house is still safe? Which friends can be trusted? How do you answer when your child asks whether the person who killed their father might come back?

Assassination turns a family into a symbol, and symbols are constantly handled by strangers.

The weight of being the “living memorial”

Coretta Scott King, Myrlie Evers-Williams, and Betty Shabazz were each drafted into a role they did not audition for: living memorial.

A living memorial is expected to be presentable. It is expected to show up on time and to speak in ways that do not make donors uncomfortable. It must absorb the projections of supporters and the hostility of enemies. It must be both dignified and accessible, both maternal and political. It must grieve without seeming “unstable,” and it must continue without seeming “cold.”

The difference between these women is not whether they accepted the role. It is how they shaped it to protect their children and assert control over their husbands’ narratives.

Coretta Scott King moved quickly to institutionalize her husband’s legacy in a way that would not depend solely on memory or on the goodwill of political leaders. The King Center states that on June 26, 1968—less than three months after the assassination—she founded the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Center as the official living memorial, later renamed the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change. The speed is startling until you consider what delay would have meant: a vacuum into which others could pour their own versions of King, their own priorities, their own profits.

Myrlie Evers-Williams’s living memorial was, in part, a legal insistence. The killer had not been held accountable; the story was unfinished. Her life after 1963 became a decades-long argument with the state of Mississippi and with a national tendency to move on. Even popular histories now frame her pursuit with a kind of awe: History.com describes her refusal to back down and her fight to reopen the case over nearly 30 years. The official record—again, through the National Park Service—confirms what her persistence ultimately produced: a conviction in 1994.

Betty Shabazz’s living memorial was built under different conditions. Malcolm X’s legacy was—and remains—contested terrain: claimed by activists and mainstream politicians, invoked as threat and inspiration, simplified into a handful of quotes. Shabazz pursued higher education and a professional life that positioned her not just as a widow but as an educator and institutional principal; sources describe her later work at Medgar Evers College and her academic trajectory, including doctoral study. In other words: she did not only preserve a legacy. She constructed a platform from which to speak about it without begging for permission.

Still, the public rarely allows a widow to be only a builder. It wants her to be a vessel.

Motherhood with an audience

In the years after their husbands’ assassinations, each woman faced motherhood in its most exposed form: parenting while watched.

Coretta Scott King’s children became, in effect, part of the public archive. They appeared at memorial events, marched in ceremonies, and were asked—implicitly and explicitly—to behave in ways that honored a father they could not grow up with. The King Center itself would become a workplace and a locus of family debates about stewardship. But before there was a center and a holiday campaign, there was the immediate reality of a household with four children and a nation demanding appearances.

Myrlie Evers-Williams’s children inherited not only grief but danger. Medgar Evers had been targeted; threats did not simply evaporate because the gunman had fired. For a Black mother in Mississippi in 1963, raising children after political violence was not a therapeutic metaphor. It was a security problem.

Betty Shabazz’s motherhood after 1965 was a relentless act of balance—protecting daughters while the world tried to define their father as either prophet or menace, often ignoring the complexity of his political evolution. Accounts emphasize that she did not remarry and raised six daughters alone while building her professional and speaking life.

There is a particular cruelty in the way public grief invades children’s development. A child does not lose a father once. A child loses a father repeatedly—in Father’s Day crafts at school, in graduation crowds, in the way other children talk about “my dad,” in the way adults say, “He would be so proud,” as if pride is a substitute for presence.

And the widow loses something repeatedly too: the ability to grieve privately, to be incoherent, to collapse without consequence. These women had to be steady because instability would have been punished—not only by political opponents but by a public that demands Black women be strong as a condition of being heard.

Coretta Scott King: Architecting a legacy while raising four children

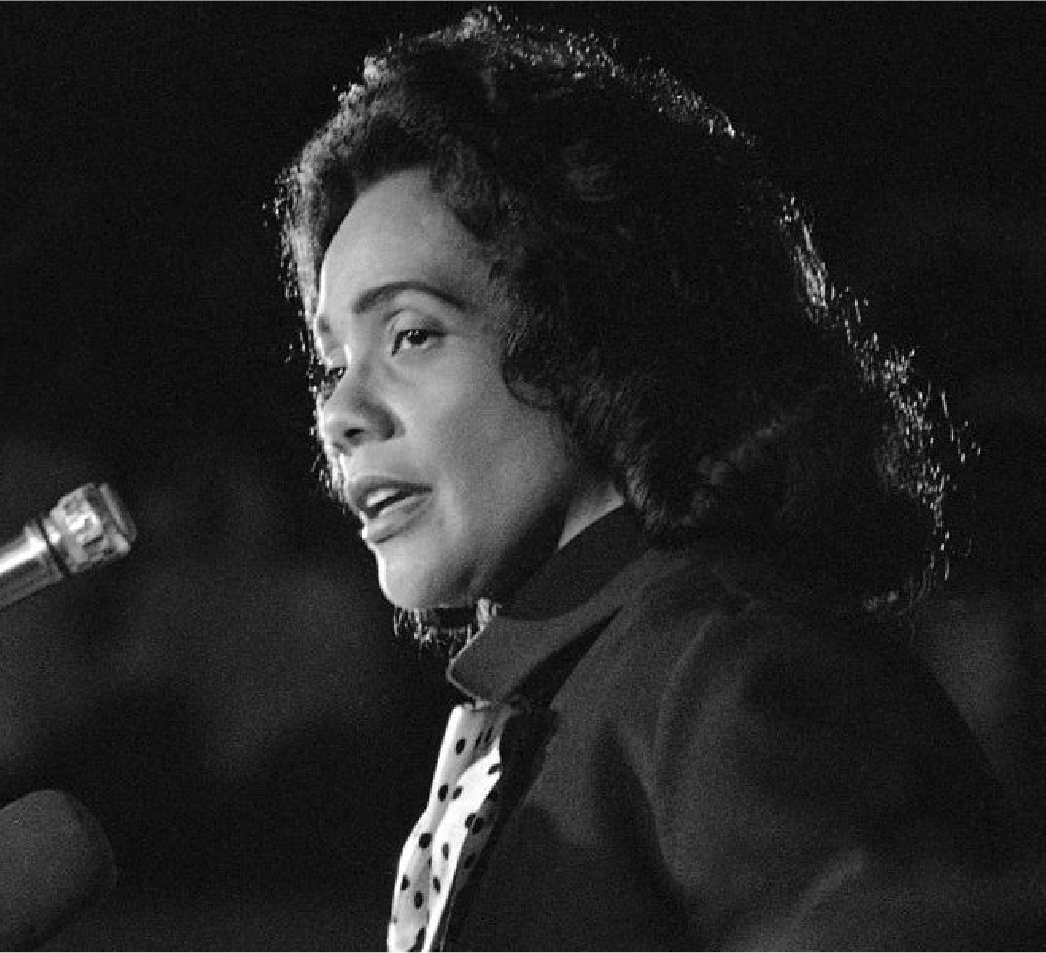

The nation often speaks of Coretta Scott King as a guardian of Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream, but that language can flatten the scale of what she actually built.

Within months of the assassination, she founded what would become The King Center, establishing an institutional home for her husband’s philosophy and papers and for the practical work of training in nonviolence. Stanford’s King Institute notes that after April 4, 1968, she devoted much of her life to spreading his philosophy of nonviolence, and that just days after the assassination she led a march in Memphis in support of the sanitation workers’ strike. The sequencing matters: she did not retreat from public life to “heal” before acting. She acted through the wound.

To do that while raising four children required more than conviction. It required a recalibration of identity. Before 1968, Coretta Scott King was already an activist—an organizer, a performer who used “freedom concerts” to raise funds, a political partner. After 1968, she became something else: the person expected to translate King’s work into forms the nation could absorb.

That translation work is exhausting because it is never neutral. It involves choosing what to emphasize and what to correct, deciding which alliances will keep the mission alive and which compromises will distort it. It involves defending the fullness of King’s agenda—on poverty, war, labor—against those who prefer him as a harmless saint.

In the 15-year battle to establish Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Coretta Scott King served as a central campaigner and public face of the effort. The National Museum of African American History and Culture recounts the prolonged push and the eventual signing of the bill by President Ronald Reagan in 1983, with Coretta Scott King present. The Associated Press similarly describes years of lobbying and coalition-building, with Coretta Scott King among the civil rights leaders who kept pressure on Congress.

It is difficult to overstate what that meant in family terms. National holiday campaigns are not hobbies. They require constant travel, meetings, donor cultivation, and the willingness to endure backlash. And backlash was part of it: even after the law, states resisted. Time’s account of the first federal observance in 1986 notes that several states initially refused to recognize the holiday and that acceptance was uneven for years. Every political battle she fought in public life was also time away from her children—children who had already lost enough.

Here is the paradox at the center of her story: to honor her husband, she had to be absent from home sometimes; to raise her children well, she had to be present. The public expected a seamless combination of both, as if sacrifice has no consequences. She had to invent a way to be a national figure without surrendering the intimacy of mothering.

Coretta Scott King’s motherhood, then, is part of her political biography. Because what she was really doing—besides campaigning and institution-building—was raising the next set of custodians. The King children grew up in the pressure chamber of American symbolism. Their father’s name could open doors and also lock them in a narrative they did not choose. Their mother’s task was to protect them from being turned into relics.

The King Center would become an arena where family legacy and public history overlapped. Coretta Scott King’s decision to create an institution did not merely preserve her husband’s memory; it created a place where the family could anchor itself in something tangible, something that did not depend on the shifting moods of national politics.

But institutions are also magnets for conflict. They attract competing interests, including within families. The public saw the holiday and the ceremonies. The private family lived through the strain of being perpetually “on duty.”

What makes Coretta Scott King’s story so instructive is that she refused the role of passive widow. She did not simply protect a name. She expanded the project.

Myrlie Evers-Williams: The long war for justice, with children in tow

If Coretta Scott King’s post-assassination life demonstrates how legacy becomes institution, Myrlie Evers-Williams demonstrates how legacy becomes time—how it can stretch into decades of persistence against a legal system content to let a murder fade.

Medgar Evers was killed in 1963; two trials in 1964 ended without conviction; and then the case sat in the shadow of American amnesia until new energy and evidence pushed it forward again. The National Park Service’s account is both straightforward and quietly devastating: in February 1994, a mixed-race jury convicted Byron De La Beckwith and sentenced him to life. For Myrlie, that conviction was not merely a courtroom victory. It was the completion of an obligation to her children: proof that the state could be forced, however belatedly, to treat her husband’s life as worth justice.

Popular narratives often describe her as unrelenting, and the description fits not because she was superhuman but because the alternative—acceptance—would have been another kind of death. History.com writes that others might have backed down, but she fought to have the case reopened after waging the battle for nearly 30 years.

To wage that battle while raising children is to live with constant reopening. Each attempt to move the case forward required revisiting the murder, reentering the public story of it, inviting scrutiny and sometimes harassment. It required teaching children, in real time, what it means to pursue justice in a country where justice can be delayed until it nearly loses meaning.

Myrlie’s public life expanded beyond the case. She became a major civil rights leader in her own right, including serving as chair of the NAACP’s board of directors in the 1990s. The NAACP’s biographical profile emphasizes her leadership and her role as chair from 1995 to 1998. The Washington Post, reporting at the time of her election, framed her as long known primarily as a widow, now stepping into the responsibility of reviving an embattled organization.

That framing—widow first, leader second—was common, and it is part of the burden these women carried: they were constantly being introduced through absence. Yet Myrlie Evers-Williams’s work demonstrates how a widow can refuse to stay inside the borders of her tragedy. She moved into the broader architecture of civil rights governance, where budgets and politics and internal reform can matter as much as street protest.

Even the recent treatment of her archival life reinforces that she has become, in effect, a primary source of the movement’s private record. The Washington Post reported in 2025 on her decision to place her archive at Pomona College, describing a collection that includes campaign and personal materials and reasserting her role as both witness and actor.

For her children, this meant growing up not only with the story of their father but with the ongoing demands of their mother’s public mission. They had to watch her return, again and again, to the site of pain. They had to watch her turn grief into strategy. They also had to live as a family that could never fully separate private life from public meaning.

When a widow pursues justice for decades, she is not just fighting a killer. She is fighting the erosion of attention—the national tendency to declare that enough time has passed, that the wound should be “over.” Myrlie Evers-Williams’s life argues the opposite: that time does not absolve a crime, and that memory is a form of resistance.

Betty Shabazz: Safeguarding a contested legacy while raising six daughters

Betty Shabazz’s widowhood began in a moment of chaos and continued under a uniquely complicated public gaze. Malcolm X’s life and death were already surrounded by suspicion, internal movement conflicts, and government scrutiny. To be his widow was to inherit not only admiration but conspiracy theories, surveillance anxieties, and the constant attempt by outsiders to simplify him into something usable.

Shabazz also inherited immediate, crushing logistics: six daughters to raise, and two of them arriving after their father was gone. The Guardian’s account of biographical reporting underscores how young the children were and that she was pregnant with twins who would be born months after the assassination.

If Coretta’s public work is often framed as “continuing the dream” and Myrlie’s as “seeking justice,” Shabazz’s is often framed as “survival.” That framing can be reductive, but it points to something real: the sheer economic and emotional load of single parenthood at that scale, under that spotlight, while trying to preserve your children’s right to a childhood that isn’t swallowed by history.

Shabazz chose education as one route to stability and authority. Accounts describe her completing degrees and earning a doctorate, and later working at Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn. Those details matter not because credentials are the point, but because education gave her institutional standing. It allowed her to speak about Malcolm X not merely as grieving spouse but as Dr. Shabazz—an educator and public intellectual whose voice could not be dismissed as purely emotional.

Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion characterizes Shabazz as pivotal in preserving Malcolm X’s legacy and advancing a vision of Black liberation and human rights. That is a scholarly way of naming what was, in day-to-day life, an ongoing negotiation: which Malcolm does the public want, and which Malcolm did she know? Which parts of his story would her daughters inherit, and which would be distorted around them?

The Shabazz daughters became, over time, public carriers of the legacy themselves—authors, advocates, artists, and public figures navigating a world eager to either romanticize or indict their father. Mainstream profiles now routinely describe them as continuing the legacy in varied ways. But the cost of that continuation is rarely foregrounded: the daughters’ own lives, their own struggles, and their mother’s role in trying to give them both pride and freedom.

There is another layer to Shabazz’s story that complicates any tidy narrative of triumph. In 1997, after she had taken in a grandson amid family turmoil, a fire set in her apartment left her with catastrophic burns; she died weeks later. Even in death, the public turned her into a scene: memorial services with prominent attendees, the optics of inter-movement solidarity.

But to focus only on tragedy is to miss her agency. Shabazz spent decades shaping how Malcolm X was understood, insisting on his intellectual seriousness and his human evolution, refusing portrayals that reduced him to menace or caricature. In doing so, she protected her daughters from inheriting a father’s name as a burden of misunderstanding.

Three strategies for survival: Institution, justice, and education

If you stand back from the individual biographies, three strategies emerge—each shaped by circumstance and personality, each tethered to motherhood.

Coretta Scott King built an institution quickly because she understood that memory needs infrastructure. Founding The King Center was not only a tribute; it was an assertion of control over archives, interpretation, and training. Her subsequent leadership in the campaign for a federal holiday translated grief into a civic ritual that would force the nation to confront King annually, whether it wanted to or not.

Myrlie Evers-Williams pursued justice across decades because her children’s inheritance required a conclusion that the courts had refused to provide. The 1994 conviction did not resurrect Medgar Evers, but it publicly affirmed that his murder was not an acceptable political outcome. Her later leadership at the NAACP placed her inside the machinery of civil rights advocacy, extending her work beyond her own family’s case.

Betty Shabazz pursued education and institutional legitimacy, both as financial stability and as rhetorical authority, while raising six daughters and defending a legacy that America alternately feared and fetishized. Her strategy was, in part, to become unignorable on her own terms.

None of these strategies were clean. Institutions draw politics. Court cases reopen trauma. Education does not shield a family from surveillance or from the psychological consequences of loss. But each strategy reveals the same underlying goal: to give children something steadier than chaos.

The hidden work: Money, safety, and the right to be ordinary

The public memory of these widows tends to emphasize symbolic moments: the funeral, the marches, the speeches. The private reality included the tasks that rarely make history books but determine whether families survive.

Money becomes immediate. Political assassinations can generate donations, but they can also generate instability. A widow may be offered support that comes with conditions: appear here, endorse this, keep quiet about that. She may also face economic vulnerability, especially if her husband’s work was not designed to produce wealth.

Safety becomes a daily calculation. Each family had reason to fear further violence. Myrlie Evers-Williams lived in a Mississippi environment where white supremacist intimidation was not abstract; it was the context. The idea of raising children under that shadow is not merely “difficult.” It is a continuous risk assessment: where can the children play, who watches them, what do you do if the phone rings late at night?

For Shabazz, safety included the risk that publicity itself creates. A famous name can attract not only admirers but threats, opportunists, and those seeking proximity for their own agendas. For Coretta, safety existed alongside constant movement travel and the pressures of being a national emblem.

Then there is the right to be ordinary. This is perhaps the most underrated aspect of their motherhood. Children need ordinary routines: homework, jokes, friendships, small disappointments. Public tragedy threatens to eliminate the ordinary by turning every milestone into a commemoration. The widows’ work, in part, was to fight for normalcy—not as denial, but as a way to keep children from being consumed by an event.

This is what it means to raise children while maintaining a legacy: to insist that your child is not merely “Martin Luther King’s son” or “Malcolm X’s daughter” but a person with their own interior life.

The politics of legacy: Who owns the dead?

Legacy is not a gift passed down gently. It is a contested asset.

After King’s assassination, many Americans who had opposed him became eager to claim him, often by trimming away the parts of his message that challenged capitalism, militarism, and racial hierarchy. The holiday campaign itself became a stage where the country argued over which King would be honored. Coretta Scott King’s role required her to push back against reduction: to insist that a holiday honoring King must honor more than a single speech.

After Medgar Evers’s murder, the fight for legacy was inseparable from the fight for legal truth. Without a conviction, the story could be treated as unresolved, even deniable. Myrlie Evers-Williams’s persistence forced the state to make a definitive statement: this murder happened, and it mattered.

After Malcolm X’s assassination, the fight over legacy became especially volatile. Malcolm X’s ideological evolution—his break with the Nation of Islam, his broader internationalism—has often been flattened. Shabazz’s task was to keep his complexity intact while the public pulled at him from both ends: demonizing him as violent or sanctifying him as myth, often without patience for the full human record.

In each case, widowhood meant becoming a gatekeeper. Gatekeeping is not always celebrated, because it can involve saying no—to filmmakers, to politicians, to activists, to those who want to borrow a name without accountability. But gatekeeping, in these stories, is maternal. It is the protective instinct applied to history: if you allow a legacy to be misused, your children will grow up inside a lie.

The children: Inheriting both pride and absence

The children in these families inherited two things at once: pride in who their fathers were, and the daily wound of who their fathers could not be to them.

Coretta Scott King’s children grew into public roles, and the public often frames that as destiny. But destiny is too neat a word for what happens when your childhood includes your father’s assassination as a national trauma. The King family’s later public stewardship—through The King Center and public commemorations—underscores how the children became part of the institutional legacy their mother created.

Myrlie Evers-Williams’s children grew up alongside a case that would not end. Even if she shielded them, they would still live with the reality that their father’s killer walked free for decades. When the conviction finally came in 1994, it did not erase those years; it redefined them, turning endurance into vindication.

Betty Shabazz’s daughters inherited a father whose name carries global recognition and intense controversy. Modern reporting describes how they have continued his legacy in public ways, including advocacy and legal action related to the circumstances of his death. But again: public continuation is not the same as private healing.

What these children also inherited was their mothers’ example. Watching a mother rebuild a life after political violence teaches children something about power: that it can be seized back, piece by piece, through persistence.

Solidarity among widows: Shared grief, shared strategy

There is a quieter subplot in these stories: the way these widows’ lives intersected across movement lines.

The civil rights movement is often narrated through ideological splits—nonviolence versus self-defense, integrationist versus nationalist. But grief can create an unexpected coalition. Over time, these women appeared in the same rooms, at memorials, at commemorations, at the kinds of events where history is curated in real time. Reporting and archival accounts of memorial events note prominent figures and fellow movement leaders present at Shabazz’s memorial service, including Coretta Scott King and Myrlie Evers-Williams.

That detail matters because it suggests something the public rarely considers: widowhood is a form of expertise. Who understands the pressures of being turned into a symbol better than another person who has been turned into a symbol? Who understands the experience of raising children under that kind of spotlight better than someone else who has had to do it?

Their solidarity was not always loud or public, but it did not need to be. Sometimes solidarity is simply recognition—the sense that you are not alone in the most isolating category imaginable.

The cost of resilience

Resilience is often treated as a compliment. It can also be a trap.

To call these women resilient is true, but incomplete. Resilience is what people praise when they do not want to sit with the cruelty that required it. Resilience can become an expectation: you survived once, so you must keep surviving, endlessly, without complaint.

Coretta Scott King’s life after 1968 was filled with accomplishments that could justify an entire political biography on their own: institution-building, holiday advocacy, global leadership. But resilience also meant years of living inside the story of her husband’s death while the public continually requested her presence as proof that the nation had “moved forward.”

Myrlie Evers-Williams’s resilience meant decades of returning to the same file, the same testimony, the same arguments—living with a clock that did not care how tired she was.

Betty Shabazz’s resilience meant building a professional identity and raising six daughters while Malcolm X’s name continued to trigger fear, admiration, and opportunism, and while she navigated family hardships that culminated in her tragic death.

What unites them is not that they were invincible. It is that they kept choosing, again and again, to do the next necessary thing.

A different way to measure legacy

America tends to measure legacy through monuments: buildings, holidays, famous quotes. Those things matter, and these women helped create them. The King Center exists because Coretta Scott King moved quickly and decisively. The Medgar Evers murder conviction exists because Myrlie Evers-Williams refused to accept closure without justice. Malcolm X’s legacy remains vivid in part because Betty Shabazz insisted on his humanity and intellectual seriousness and built her own platform as an educator.

But there is another measure of legacy—one that does not fit cleanly on plaques. It is the measure of what children carry.

If you want to understand what these widows did, imagine the daily accumulation of small decisions: whether to attend a public event or stay home for a child’s fever; whether to correct a journalist’s misquote or ignore it to preserve energy; whether to move houses for safety; whether to let a child watch footage of their father; whether to speak the dead man’s name at the dinner table.

Each decision was a stitch in a life rebuilt.

In the end, Coretta Scott King, Myrlie Evers-Williams, and Betty Shabazz did something that does not sound grand until you try to do it yourself: they kept their children alive inside a country that repeatedly demonstrated how cheaply it valued Black life, even heroic Black life. They kept legacies from being stolen outright, even when the nation tried to claim the men while ignoring the women. And they showed, with a clarity that history sometimes forgets, that assassination is not only a political event—it is a family event, with a long aftermath measured in school years, birthdays, and the slow work of turning grief into something that can stand.

That work is not a footnote to the civil rights era. It is one of its most instructive chapters: the chapter that begins when the cameras leave, when the condolences thin out, when the widow returns home and realizes she must become, at once, mother, strategist, security officer, archivist, and translator of a man the nation will never stop arguing about.

The day after the gunshots, the children still needed breakfast. The widows provided it. And then, somehow, they built the rest.