Gladys West’s career belongs to the class of work that modern life quietly leans on.

Gladys West’s career belongs to the class of work that modern life quietly leans on.

By KOLUMN Magazine

In the era when a blue dot on a screen can tell you where you are—down to the corner, sometimes to the side of the street—our dependence on location feels natural, almost biological. We navigate without thinking, surrendering the ancient work of wayfinding to satellites and software. But the ease is an illusion: the convenience rests on a demanding, exquisitely exacting story about the Earth itself, a planet that is not a perfect sphere and not even a perfect ellipsoid, but a complicated, dynamic shape whose surface, gravity, tides, and subtle bulges make certainty difficult.

Gladys West built a life inside that difficulty. Over a four-decade career as a mathematician and computer programmer for the U.S. Navy’s research complex at Dahlgren, Virginia, she helped convert satellite measurements into increasingly accurate models of the planet’s shape and gravitational field—work in satellite geodesy that became part of the larger scaffold on which modern Global Positioning System technologies operate. For years, her contributions were largely invisible outside specialized circles. Then, late in life, she was publicly recognized as one of the “hidden figures” whose painstaking computations shaped a technology now embedded in everything from smartphone maps to emergency response, shipping logistics, aviation systems, precision agriculture, and financial timing infrastructure.

West’s story is sometimes told as a morality tale about invention—who “created GPS,” who was denied credit, who should have been awarded what. Those questions matter, but they can flatten the truth. GPS is less a single invention than a layered system: a constellation of satellites, receivers, timing protocols, control segments, orbital mechanics, and a dense underworld of mathematical models that correct for the planet’s imperfections. West did not singlehandedly invent GPS. What she did, by multiple accounts from the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Navy, and engineering and technology publications, was significantly evolve the geodetic and data-processing foundations that make satellite positioning accurate enough to trust. In a domain where errors compound quickly—where a small misread of Earth’s shape can widen into a larger navigational mistake—her work was a kind of disciplined caretaking.

That distinction—between invention and infrastructure—helps explain both her significance and her long absence from popular narratives. Infrastructure is rarely celebrated while it is being built. It becomes visible when it fails, or when the cultural moment changes enough to ask who carried the work. In West’s case, recognition arrived after the public had begun to reexamine the history of computing and the quiet labor performed by women, particularly Black women, in mid-century technical institutions. The language of “hidden figures” is now familiar; it also risks becoming a shortcut. West’s life is best understood not as an exception but as a lens: it reveals how talent moved through segregated schools, historically Black colleges and universities, government labs, and the long corridors of defense research, often in ways that public memory did not preserve.

A childhood shaped by scarcity, and by school

Gladys Mae Brown was born in Virginia in 1930, in a rural world structured by segregation and by the economics of agricultural labor. Later profiles describe her early life in Dinwiddie County as marked by limited opportunity and by a clear understanding that education could be an exit—one of the few socially sanctioned routes out of the constraints placed on Black families in the Jim Crow South. In accounts that emphasize her academic brilliance, she emerges as a student who recognized, early on, that grades could function as a passport.

That emphasis on school was not merely aspirational; it was strategic. West has been described as graduating at or near the top of her high school class, a distinction that helped her pursue higher education at a time when resources for Black students were systematically restricted. She attended Virginia State University, a historically Black university, where she earned degrees in mathematics and developed the skills that would later translate into computing work for the federal government.

The contours of that early pathway matter because they sit at the intersection of two American histories: the history of Black educational ambition as a response to enforced limitation, and the history of the Cold War state as an employer for technical talent. The United States, in the middle of the twentieth century, was rapidly building an apparatus of research labs and proving grounds—sites where mathematics, engineering, and early programming were not abstract pursuits but instruments of national security. That apparatus, like the broader society, was hardly immune to racism. Yet it required skilled labor, and in pockets—sometimes grudgingly, sometimes through local circumstance—it created openings for people who were otherwise excluded from elite institutions.

Virginia State University did not simply train West in mathematics; it helped position her in that thin, consequential corridor between educational accomplishment and federal technical work. In later tributes, the university framed her life as a barrier-breaking trajectory and a point of pride for an institution that, like many HBCUs, produced technical leaders whose names were not always amplified in mainstream histories.

Before GPS was a consumer product, the Earth had to be computed

In 1956, West began work at what was then the Naval Proving Ground in Dahlgren, Virginia—later known as the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division—joining a technical environment that was pioneering, highly hierarchical, and shaped by the tensions of the Cold War. Official accounts note that she was among the earliest Black employees there, and among the first Black women hired into that research setting. The point is not a demographic footnote. It is a description of the social atmosphere in which her professional identity formed: a place where she had to be excellent and, often, careful.

The work itself was complex and evolving. Early satellite and space-era programs demanded new forms of computation—first human “computers,” then room-sized machines, then increasingly sophisticated programming. West’s career spanned that transition. In Air Force materials honoring her, she is described as part of a small group of women doing computing work for the U.S. military in the period before electronic systems became dominant. The phrasing is revealing: it suggests a labor world where mathematical rigor and repetitive calculation were central, but where the cultural status of that work—who received public credit—was uneven.

West worked on multiple projects over the decades. Among those cited in official and trade accounts is an astronomical study in the early 1960s involving the motion of Pluto relative to Neptune. It is an example of the breadth of technical work at Dahlgren and of her ability to operate inside projects that required precision and persistence. Such studies also point to an underappreciated fact about Cold War research labs: they were often doing “basic” science and applied defense work simultaneously, because both supported the larger project of understanding trajectories—of planets, of satellites, of anything that moves through space with consequences on Earth.

Over time, the center of gravity in West’s work shifted toward geodesy—the science of measuring and modeling the Earth. Geodesy can sound esoteric, but it underpins navigation. To know where something is on Earth, you need a reference frame: a mathematically described planet against which positions can be measured. The Earth is lumpy; it bulges at the equator; its gravity varies; its surface rises and falls; the oceans are not flat; the “sea level” used in maps is itself an approximation. West helped translate satellite altimetry and other measurements into computational models of these complexities—models that could be used to calculate positions more accurately.

The technical vocabulary that appears in profiles of her work—geoids, ellipsoids, vertical deflection, radar altimeters—signals a career built around reducing uncertainty. One of the more specific artifacts associated with West is a 1986 technical report on data processing for the GEOSAT satellite radar altimeter, which engineering publications have described as improving calculations that increased the accuracy of geodetic models. In the ecosystem of satellite positioning, this kind of work matters because accuracy is not a single breakthrough; it is the cumulative result of countless small reductions in error. A receiver can only be as confident as the models and corrections it relies on.

There is a temptation, in telling such stories, to translate complexity into a single romantic sentence: she “made GPS possible.” That is broadly true in the sense that her work contributed to the foundations of the system. But it is more accurate—and more respectful of the discipline—to say that West helped build the geodetic and computational conditions required for satellite navigation to function reliably at scale. She worked in the technical layers that most users never see: processing satellite data, refining Earth models, and supporting the accuracy of positioning systems.

Work in the shadow of classification

West’s long relative anonymity is partly explained by classification and by the culture of defense research. Many of the people who supported early navigation and satellite programs were not public-facing inventors; they were government employees whose output was measured internally and whose publications, when they existed, often appeared as technical reports rather than mass-market books.

But classification is not the whole story. West’s delayed recognition also resembles a broader pattern: in institutional settings, the people who build foundations—especially women and minorities—are often less visible than those who manage programs, present results, or become the public face of a technology. That pattern has been documented in histories of computing and has become a subject of renewed debate in the last decade. West’s late-life visibility, in other words, did not come only because the public “finally noticed.” It came because a cultural shift made the question of unnoticed labor harder to ignore.

One often-cited detail in narratives about West’s recognition is that her role became more widely discussed after an Alpha Kappa Alpha community connection surfaced her biography and achievements to people who were surprised to learn what she had done. The Atlanta Voice, for instance, credited the spreading of her story to a friend who encountered that biography and then sought to publicize it. The point is not the origin story itself so much as what it implies: recognition did not flow automatically from the institution outward. It moved through networks—Black professional and social networks—that have historically served as informal archives when formal ones failed.

Honors that arrived late, but mattered

When public honors came, they came in a cluster—evidence of an overdue institutional correction. In 2018, West was inducted into the U.S. Air Force Space and Missile Pioneers Hall of Fame during a Pentagon ceremony, an accolade described by Air Force materials as one of the service’s space command honors. Coverage of the induction highlighted her decades of computing work and linked it directly to the accuracy of satellite geodesy and navigation.

In 2021, she received the Prince Philip Medal from the U.K. Royal Academy of Engineering, which the academy described as its highest individual honor and noted as the first time the medal had been awarded to a woman in its history. The citation language around that award explicitly connected her mathematical modeling to GPS-enabled mapping and to the broader study of Earth measurements—an important reminder that her work sat at the intersection of navigation and planetary science.

That same year, the Webby Awards recognized her with a Lifetime Achievement honor, reflecting a widening understanding that “digital” life depends on older, deeper technical labor—on the foundational science and engineering that makes modern platforms and devices operate.

More recently, Navy-linked recognition continued. NAVSEA reported honoring West with a Freedom of the Seas Exploration and Innovation Award, explicitly tying her career at Dahlgren to satellite geodesy and the GPS models that followed. The Navy’s language is significant because it positions her not merely as an inspirational figure but as a technical contributor within the service’s own institutional story.

To the extent that public memory is built out of ceremonies, those moments mattered. They created a record: photographs, official press releases, and searchable citations that future historians can use. West’s papers are also preserved in archival form through institutional collections, which list milestones including the Air Force Hall of Fame induction and other honors—evidence of a life that, by its final decade, was increasingly documented.

The politics of credit, and why West’s story became a debate

No story about West’s significance can avoid the controversy surrounding major prizes and who receives them. In 2019, TIME published an account of the Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering awarded to four male figures associated with GPS development, and the public criticism that followed, noting that West’s contributions had been highlighted as essential by advocates who questioned why she was not among the recognized. The prize committee’s explanation—that her contribution was not “fundamental” enough—drew backlash as an example of how institutions define “fundamental” in ways that elevate certain forms of leadership while downplaying the infrastructure work that makes systems function.

This debate can become reductive when it is framed as a simple omission. The deeper issue is how credit is allocated in complex, multi-decade systems. GPS was not made by a single person; it was made by networks of engineers, mathematicians, program managers, military institutions, contractors, and researchers across agencies and decades. Yet prizes often demand a small number of names. That structural requirement creates a kind of narrative violence: it compresses distributed labor into a few biographies.

West’s case shows why that compression matters. If you treat GPS primarily as an engineering architecture—satellites, signals, receivers—you might elevate the public architects. If you treat GPS as a measurement problem—how to define position accurately on an irregular Earth—you are forced to acknowledge the geodesists and modelers. West’s work sits in that second category. It is foundational in function even if it is less visible in storytelling.

An Atlantic essay about location-sharing technology made this point almost in passing, noting that West was central to Navy GPS development work but that she was not publicly credited until after retirement. The sentence is small; the implication is large. Technologies that feel intimate—apps that track friends, phones that tag photos—often depend on labor performed far from the consumer gaze, inside institutions that historically did not distribute recognition evenly.

The significance of Gladys West, beyond the GPS shorthand

West’s importance can be described in three overlapping ways: technical, institutional, and cultural.

Technically, she represents the geodetic backbone of satellite navigation. Profiles in IEEE Spectrum and other technical outlets emphasize her role in leading analysts who used satellite sensor data to calculate Earth’s shape and to refine models that support accuracy. Even when accounts differ on phrasing—whether she “laid the groundwork” or “made GPS possible”—they converge on the idea that her mathematics helped reduce error in systems that depend on precision.

Institutionally, she is a case study in the Cold War laboratory as a complicated site of opportunity. Dahlgren was a federal research facility in a segregated America. West’s hiring and advancement there did not mean the institution was equitable; it meant that talent could, sometimes, push through narrow doors. Reporting on her life has emphasized the barriers she faced and the reality that recognition often flowed more readily to white colleagues. In that sense, her story reveals both the possibilities and the limits of mid-century “merit” narratives.

Culturally, West’s late-life recognition aligns with a broader effort to revise the public history of science and technology to include the people whose labor was routinely minimized. The “hidden figure” framework has value here, but West’s life also complicates it. She was not a footnote in her own workplace; she built a decades-long career, earned advanced credentials, and continued learning well after retirement. She completed a Ph.D. later in life, a detail preserved in archival descriptions of her papers. That decision suggests a person who saw education not as a phase but as a lifelong practice.

It is also important to recognize what West’s story does not resolve. Celebrating her can become a substitute for changing the systems that made her recognition late. There is a risk in the current appetite for rediscovered pioneers: institutions may tell inspiring stories while leaving intact the cultures that obscure present-day contributors. West’s legacy, at its most useful, is not only a source of pride. It is a diagnostic tool—a way to examine how credit works, how talent is nurtured, and how technical labor is remembered.

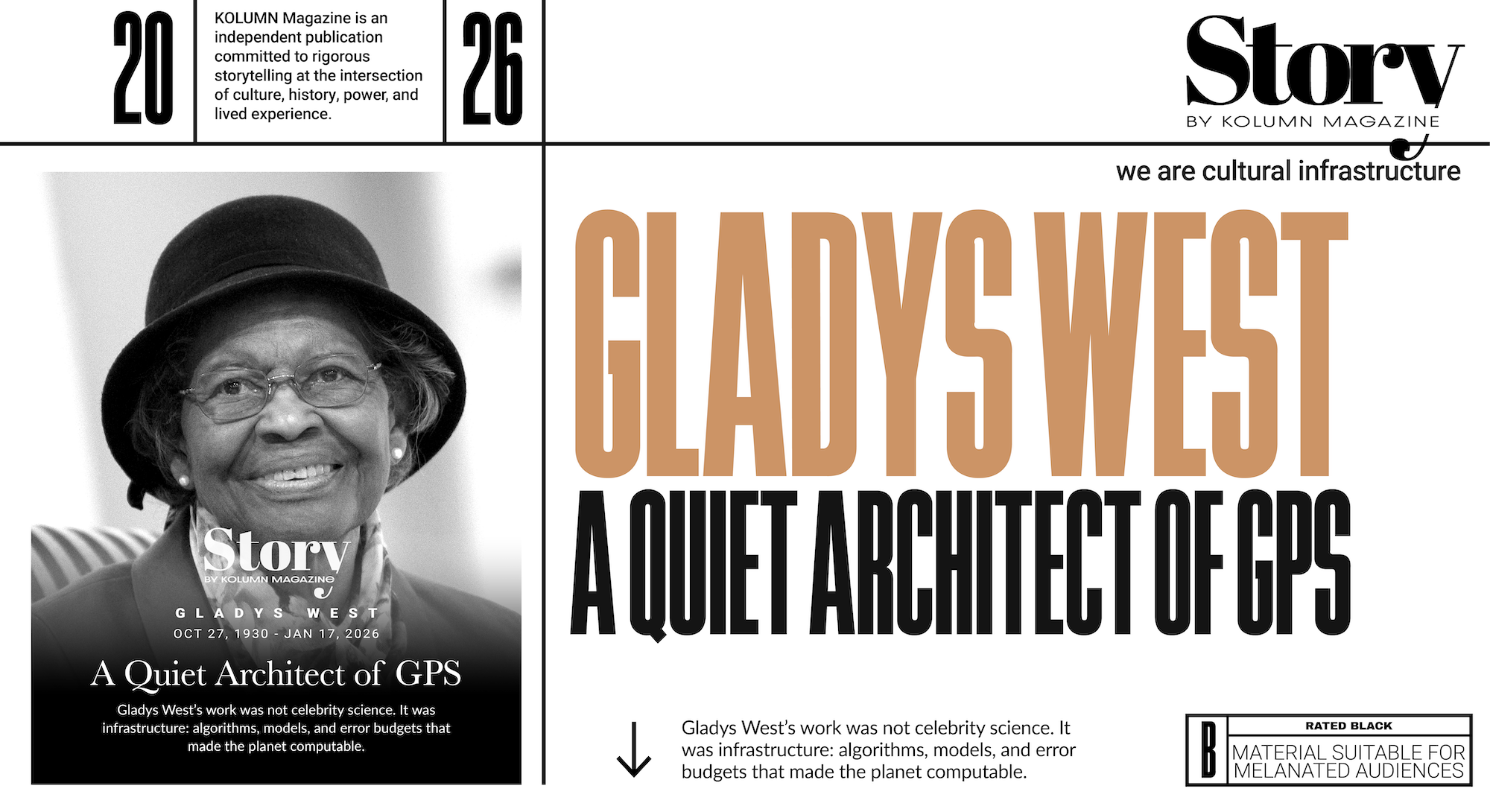

A life that ended as the world learned her name

In January 2026, news outlets reported that West had died at age 95, with tributes emphasizing the everyday reach of her work. Virginia State University issued a memorial statement framing her as a pioneering alumna and a barrier-breaker in mathematics and science. NPR coverage described her as a Black mathematician whose work helped develop GPS, reinforcing the central theme that had, by then, become the dominant public summary of her career.

Even KOLUMN Magazine—through its social media presence—joined the chorus of remembrance, reflecting how her name had come to function as a symbol of Black technical excellence and long-overdue credit.

It is tempting to end the story with a neat moral: the world corrected itself, the hidden figure was revealed, justice arrived. But West’s life suggests a more complicated ending. Recognition came, but late. The GPS story continues, and credit allocation remains contested. The deeper cultural shift—toward a fuller accounting of who built the modern world—is unfinished.

What is finished, and undeniable, is the shape of her contribution. Gladys West’s career belongs to the class of work that modern life quietly leans on. She helped make the Earth legible to machines. She worked at the level where precision is earned rather than assumed. And in doing so, she helped turn space—satellites orbiting above a planet—into a daily human utility: the ability to locate ourselves, to find one another, to move through the world with a confidence that feels effortless only because someone, decades ago, refused to be casual about accuracy.