If the region’s premier amusements treated Black people as intruders, Black communities would create leisure on their own terms.

If the region’s premier amusements treated Black people as intruders, Black communities would create leisure on their own terms.

By KOLUMN Magazine

In the American imagination, the 1920s are lit from within: a decade of bright marquees, dance orchestras, bathing suits, speed, and modern pleasures sold as a kind of proof that the country was finally moving forward. Yet the modernity of leisure—especially mass leisure—was never evenly distributed. For Black Americans in the North and in the nation’s capital, the so-called new freedom came with old conditions: where you could sit, where you could swim, where you could stroll, and where your children could run without being reminded that the public belonged to someone else.

Amusement parks distilled that contradiction. They were built to be democratic in posture—cheap admission, thrills for the family, spectacle for everyone—and yet they often became theaters of exclusion, places where Black patrons were barred, humiliated, or threatened. The historian’s point is simple: leisure is not a footnote to civil rights. It is one of the most visible ways a society decides who is entitled to ease. The museum phrasing is blunter: Black-owned recreational spaces mattered because they offered havens of welcome and security, away from the constant risk of humiliation or violence.

In that landscape, Chicago’s Joyland Park and Washington’s Suburban Gardens were not just “places to go.” They were, each in its own scale, an argument made in timber and ticket stubs: if the region’s premier amusements treated Black people as intruders, Black communities would create leisure on their own terms. Both parks came of age in the 1920s—one in Bronzeville, the other in Deanwood—and both carried the same subtext. The rides and the games were real, but so was the deeper purpose: to make Black joy ordinary, public, and repeatable.

Their stories also share a harder truth. These parks demonstrate how quickly a community-built refuge can be destabilized when it sits inside a segregated political economy—where access to credit is constrained, where municipal priorities do not align with Black neighborhoods, and where ownership can change hands under pressure. Joyland and Suburban Gardens offered the pleasures of the era, but they also exposed the vulnerability of Black leisure when the broader system still treated Black life as conditional.

Bronzeville in motion, and a park designed to meet it

To understand why Joyland Park mattered, it helps to begin where it stood: Chicago’s South Side, in the dense, fast-growing neighborhood later remembered as Bronzeville, the “Black Metropolis” that became a national center of Black culture, business, and everyday striving in the early twentieth century. By the 1920s, the Great Migration had remade the city. Black southerners arrived with ambitions and bruises, building institutions because the city’s institutions were not built for them. The neighborhood’s energy—music, clubs, newspapers, churches, professional networks—was not merely cultural. It was infrastructural.

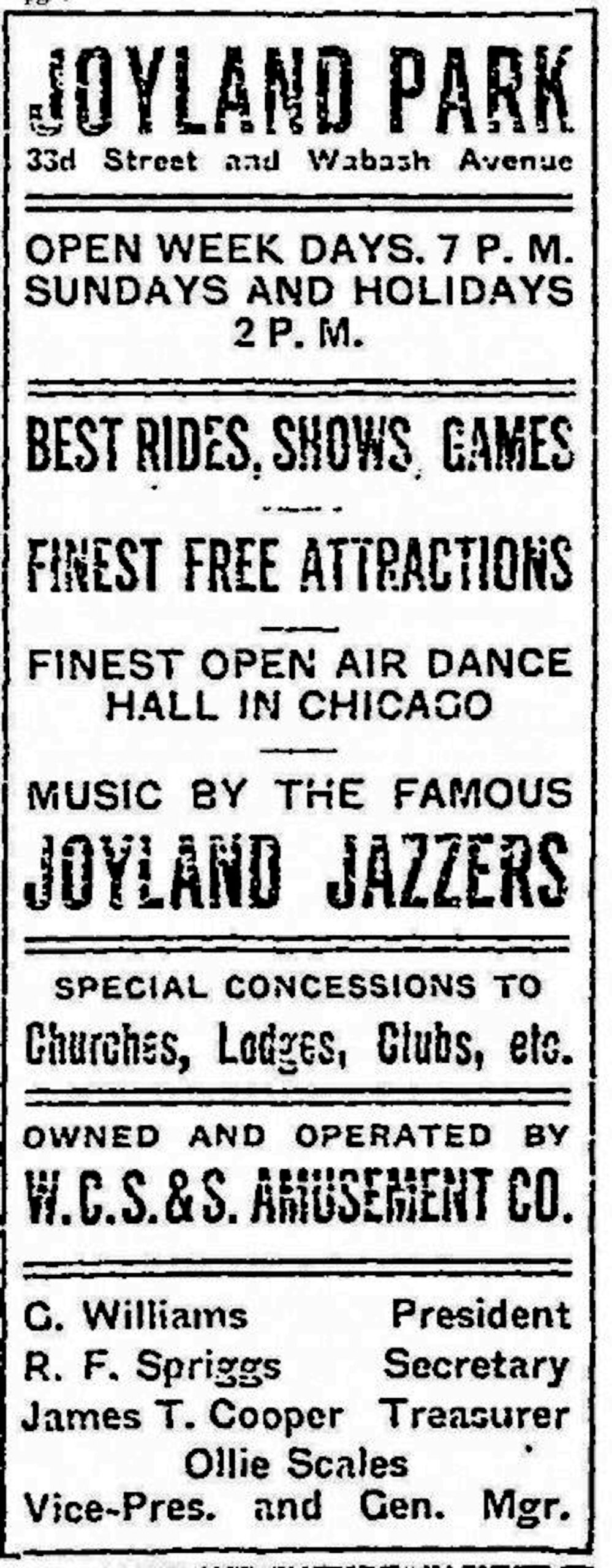

Leisure developed as part of that infrastructure. Chicago, after all, was an amusement-park city. The metropolis was dotted with white-run entertainment zones where crowds chased novelty, but those spaces were not reliably open to Black patrons. The Encyclopedia of Chicago’s account of early twentieth-century entertainment notes the point directly: African Americans were denied entrance to most venues “all but the black-owned Joyland Park,” which opened at 33rd and Wabash in 1923. That sentence, compact as it is, contains an entire social map. It tells you that leisure in Chicago was policed by race and that Joyland was the exception that proved the rule.

Joyland Park debuted in 1923 in Bronzeville as a Black-owned and -operated amusement park, explicitly created because the larger recreational world treated Black families as afterthoughts or problems. One recent interpretive account situates its creation among leading South Side figures—attorneys and media leaders—who recognized that the community’s growth demanded not only housing and jobs but a safe venue for recreation.

The park’s location is often described in practical terms—33rd and Wabash, or 3301 South Wabash Avenue—but the address is also symbolic. Bronzeville was a corridor of constraint: a neighborhood shaped by restrictive covenants and segregation, a place where Black Chicagoans were crowded into narrow boundaries even as their numbers swelled. In such an environment, a two-acre plot dedicated to pleasure was not trivial. It represented a decision to allocate scarce urban space to something other than survival.

Joyland’s amenities, as preserved in secondary histories, were more modest than the city’s giant amusement destinations, but they were carefully chosen: major rides such as a Ferris wheel, a carousel, and other attractions that replicated, at a smaller scale, the experiences available elsewhere in the city. The Smithsonian’s broader survey of Black recreational sites frames Joyland as a significant example of Black-owned leisure infrastructure in a period when segregation narrowed options; it describes Joyland’s 1923 debut in Bronzeville as a major development in Black amusement culture.

What mattered most, however, was not the ride count. It was the logic. Joyland was built to normalize a Black family’s right to the same simple things other families took for granted: a warm day’s outing, a child’s shriek on a ride, a couple’s evening stroll, the sense that the city’s pleasures were not inherently off-limits. In the context of a Chicago where racialized violence and exclusion were recent memory and present practice, the promise of a place that was “for us” carried weight that no marketing slogan could fully translate.

In a neighborhood humming with performance—jazz clubs, theaters, street life—an amusement park also functioned as a stage. People came not only to ride but to be seen. Leisure became a form of public visibility, a way to enact dignity. That is a central but often underappreciated dimension of Black recreational spaces: they allowed Black people to appear in public without the constant negotiation of white scrutiny. The park became a controlled environment where Black respectability, experimentation, romance, and childhood could coexist without the same threat of interruption.

The business of delight, and the economics beneath it

Amusement parks are emotional businesses, but they are also financial machines: land acquisition, construction, staffing, maintenance, insurance, advertising, and transportation access. In the early twentieth century, many parks were connected to transit logic; “trolley parks” were built at the ends of streetcar lines to drive weekend ridership. Even when the park itself was not owned by a transit company, its success depended on the mobility patterns of working people—days off, disposable income, the ability to travel safely across the city.

Joyland’s emergence in 1923 therefore signals more than a cultural desire. It suggests a belief among Black investors and organizers that Bronzeville could sustain a leisure enterprise—an assertion of consumer power in a city that often denied Black people full participation in the marketplace. The park’s existence argued that Black Chicago was not merely a labor pool or a “problem district,” but a community with tastes, time, and money to spend on joy.

Joyland Park (Chicago) flyer.

That argument, however, existed inside a marketplace structured against it. Racial discrimination in lending and insurance, unequal city services, and the instability produced by overcrowding in segregated neighborhoods all could affect a business like an amusement park. The park could be beloved and still precarious.

Joyland’s short lifespan—often cited as roughly two seasons, closing in the mid-1920s—has become part of its legend and its lesson. The brevity invites easy conclusions, as if failure is the natural outcome of Black enterprise under segregation. But a more careful reading suggests something else: Joyland’s closure may be better understood as evidence of how hard it was to keep Black leisure spaces solvent and protected when the broader economic and political environment remained hostile or indifferent.

If you treat Joyland as an experiment in building a “normal” amusement park in abnormal conditions, the short run becomes less a verdict on the idea than a measure of the pressure surrounding it. A neighborhood can generate demand and still be boxed in by structural constraints. A business can be culturally indispensable and still be financially fragile. That tension—between community value and market vulnerability—recurs throughout the history of Black-owned recreational sites across the United States.

And yet, a short-lived place can still produce a long cultural afterlife. Joyland’s memory persists because the need it met did not vanish when its gates closed. The desire for safe, affirming leisure did not end in 1925. It moved into other venues—ballrooms, theaters, parks, clubs—and, over time, into the long civil-rights campaign to desegregate public recreation itself.

Deanwood’s horizon, and a park built at the edge of the city

Washington, D.C., in the early twentieth century, carried a particular irony: the capital of democracy with segregation embedded in its daily life. For Black Washingtonians, leisure was shaped by the same racial boundaries found elsewhere, with a local twist—the proximity of federal power did not guarantee equal access. In fact, it often sharpened the contrast between national ideals and local practice.

Suburban Gardens opened in 1921 in Northeast Washington, in the Deanwood neighborhood, and it was, by many accounts, the first and only major amusement park ever to operate within the District’s boundaries. It was created by the Universal Development and Loan Company, described as a Black-owned real estate and development firm, and it was designed as a recreational haven for Black residents at a time when other popular parks—most notably Glen Echo in nearby Maryland—were segregated.

The park’s very name—Suburban Gardens—suggested aspiration. “Suburban” in the 1920s carried connotations of space, greenery, and escape from crowded city life. “Gardens” implied cultivation, order, and beauty. This was not marketed as a rough amusement lot. It was pitched as a first-class destination, one that could host family outings and stylish evenings, and that could do so with Black patrons as the norm rather than the exception.

The Washington Post, in a remembrance of the park, places it at 50th and Hayes Streets NE and notes that it was opened by Universal Development and Loan Co., with prominent Black figures among its owners and investors, including H. D. Woodson and John H. Paynter. The DC Preservation League’s historic-site documentation adds that Suburban Gardens opened on June 25, 1921, created specifically for Black residents and employing Black workers during segregation.

Suburban Gardens offered what an amusement park was supposed to offer: rides, games, food, a place to picnic. But sources repeatedly emphasize an additional centerpiece: the dance pavilion. The DC Preservation League notes the pavilion’s popularity in the Jazz Age and highlights performances by musicians, making the park not just an amusement venue but a cultural one. Here, leisure and music braided together, reflecting a Black Washington that was sophisticated, socially active, and hungry for public gathering spaces where Black culture could be celebrated rather than contained.

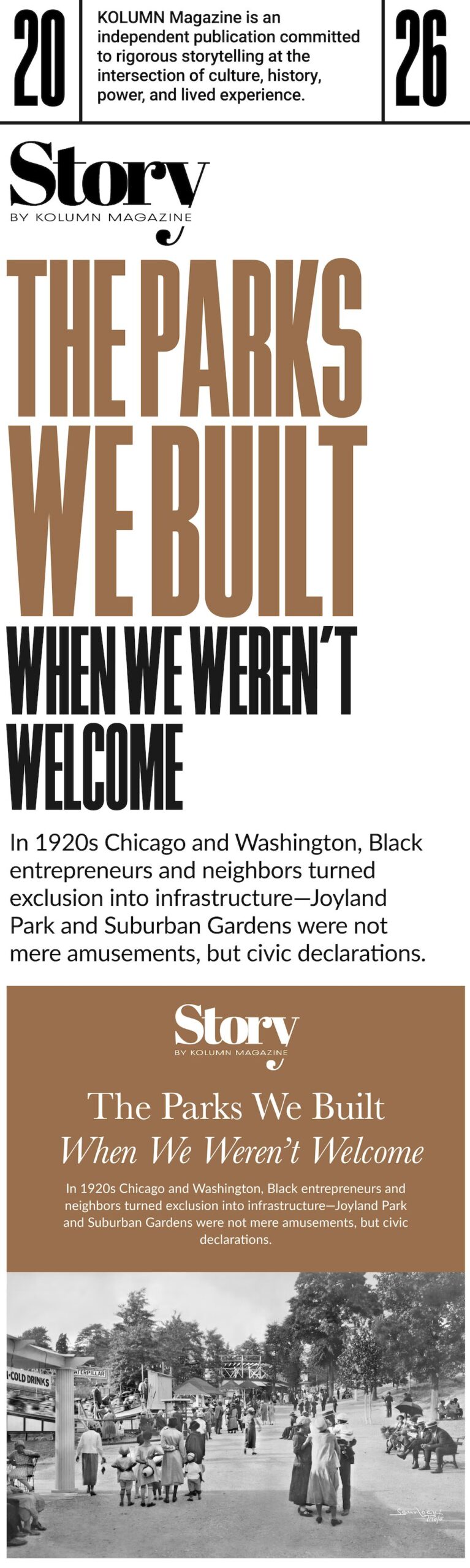

The park’s geography also mattered. Deanwood in the 1920s sat on the city’s developing edge, near the District line, a place where land could be assembled for a seven-acre recreational destination. Visitors arrived by streetcar, train, automobile, and foot, according to a Ward 7 heritage guide that describes crowds of fashionably dressed African Americans enjoying the park in the 1920s and 1930s. That image—dressed-up patrons traveling across the city for an evening of delight—also reads as a quiet rebuke to segregation’s logic. It insisted that Black Washingtonians were not peripheral citizens but central participants in the city’s social life, even when the city refused to treat them that way.

The camera as witness, the archive as survival

Suburban Gardens is unusually well served by an archival witness: the Scurlock Studio, a Black-owned photographic studio that chronicled Black Washington for decades. The Smithsonian’s collections include images of Suburban Gardens, and a Smithsonian archival blog post even discusses scanning and enhancing a negative of Suburban Gardens to make the image more legible—an inadvertent metaphor for how Black public life often survives: through careful stewardship of fragile materials.

Photographs of the park show what the written record sometimes flattens: people in motion, groups gathered, children and adults sharing space, the atmosphere of a public that is not pleading for access but exercising it. A panoramic scene of crowds near rides at Suburban Gardens appears in discussions of Scurlock’s work, underscoring the park’s role in a Black community that “blossomed in the face of adversity,” as one regional paper put it while describing the Smithsonian’s exhibition of Black photographers.

This matters because leisure history is easy to dismiss as ephemera. Tickets are thrown away, parks close, land is repurposed, and what remains is often a few sentences in a local-history file. The Scurlock images resist that erasure. They insist that Suburban Gardens was not marginal. It was lived.

In the DC case, the archive also connects the park to the broader Black urban ecosystem. The same studio that photographed families at play also documented Black professionals, Howard University events, social clubs, entertainers—an entire civic world. Suburban Gardens fits into that world as a site where Black Washington could exhale, flirt, dance, and belong.

The shadow park: Glen Echo, segregation, and the regional map of fun

No story about Suburban Gardens is complete without the regional foil: Glen Echo Amusement Park, just across the District line in Maryland. Glen Echo, by multiple accounts, enforced segregation from its beginnings, excluding Black patrons and making leisure itself a racial boundary. Suburban Gardens is repeatedly described as a welcome alternative for African Americans barred from Glen Echo.

That relationship reveals something crucial about Black recreation in the early twentieth century. Segregation did not simply deny access; it reshaped geography. It forced Black families to build their own maps of safety and pleasure—where the road trip was not just about distance but about risk, where the outing required knowledge of which gates would open and which would not.

Decades later, Glen Echo would become a civil-rights battleground, with protests in 1960 and integration by the 1961 reopening, aided by federal intervention and sustained local activism. That later history is important not as a detour but as a continuation. The existence of Suburban Gardens in 1921 is part of the prehistory of those protests: it shows how long Black families had been forced into alternatives, and how the fight for equal leisure was not sudden in the 1960s but built on generations of exclusion and improvisation.

In that sense, Suburban Gardens functioned as both refuge and indictment. It offered relief from segregation’s insult, but it also documented segregation’s reach. The park’s success was a testament to Black enterprise. It was also evidence that the region’s “mainstream” leisure spaces were operating like private clubs.

Ownership, conflict, and what happens when a refuge becomes real estate

Suburban Gardens endured longer than Joyland, operating for years into the 1930s and closing by around 1940 in many accounts. But longevity did not mean security. One widely repeated turning point came in 1928, when the park was purchased by a white movie-theater owner, Abe Lichtman, and conflict emerged over development in the surrounding community. Here again, the story turns on a familiar axis: land and control.

The park’s later transformation—its replacement by other uses, including housing, and the way the site is now largely absorbed into the ordinary fabric of the city—illustrates how Black landmarks can disappear not through dramatic destruction but through routine redevelopment. Even when a name survives on apartment buildings or local references, the original social function can be erased. Without deliberate preservation, Black leisure sites are especially vulnerable because they were often built on margins—economic, geographic, political—and those margins are precisely where redevelopment tends to be most aggressive.

A Ward 7 heritage guide explicitly notes that Suburban Gardens Apartments were erected on the site of the former amusement park, a reminder that the land’s value persisted even when the park’s cultural value was allowed to fade from broader memory.

Two parks, one argument: Pleasure as community infrastructure

It is tempting to romanticize Joyland and Suburban Gardens as quaint relics—lost parks, lost music, lost summers. That would be a mistake. Their significance is not primarily nostalgic. It is analytic. These parks clarify how Black communities approached modern life under segregation: they built parallel institutions not because separation was desirable, but because exclusion was non-negotiable.

Both parks were responses to a leisure economy that positioned Black people as outsiders. In Chicago, the Encyclopedia of Chicago’s framing—African Americans denied entrance to all but the black-owned Joyland—shows the starkness of the city’s entertainment color line. In the Washington region, the repeated linkage of Suburban Gardens to Black exclusion from Glen Echo reveals the same dynamic: Black families were expected to accept a restricted world, and Black entrepreneurs refused.

Both parks also demonstrate that Black leisure sites were, in practice, civic projects. The Universal Development and Loan Company’s role in creating Suburban Gardens—a development firm building an amusement park—signals a holistic vision of community building, where real estate and recreation were intertwined. The same can be said of the Bronzeville context: Joyland emerged in a neighborhood already defined by institution-building, from newspapers to hospitals to social clubs.

In both places, the parks served multiple constituencies at once. They were for children, for courting couples, for church groups, for workers seeking a Sunday release, for musicians and performers needing stages, for vendors earning income, for the simple act of walking through a gate and knowing you belonged. That multivalence is part of why these sites mattered. They were not niche. They were communal.

And both parks illuminate an enduring truth about the Black American experience: joy has often required planning. When the default environment is hostile or restrictive, pleasure becomes something you must design, finance, staff, defend, and remember. Black joy, in this sense, is not merely emotion. It is governance.

What their disappearance tells us about memory, and what remains at the sites

The disappearance of Joyland and Suburban Gardens is not only an urban-history fact. It is a commentary on whose leisure gets archived and preserved. When a major white-run amusement park closes, it often leaves behind extensive documentation—corporate records, postcards, nostalgia industries, preservation campaigns. When a Black-run park closes, especially in the early twentieth century, what remains can be scattered: a few photographs, a newspaper mention, a heritage marker, a line in a reference work, and community memory.

Washington has, in recent years, done more to mark Suburban Gardens through heritage materials and historic-site documentation, including the DC Preservation League’s entry and the Ward 7 heritage guide that places the park in a neighborhood narrative. The Scurlock photographs, stewarded by the Smithsonian, offer the visual record that makes the place harder to dismiss.

Chicago’s Joyland is less physically traceable, but its significance is affirmed in national and local interpretive sources that place it within the history of Black recreation and note its role as a rare Black-owned amusement option amid exclusion. In both cases, the sites have been absorbed into the ordinary city, their original purposes overwritten by subsequent development. That is typical of leisure landscapes: they are often seen as disposable. For Black communities, that disposability has been compounded by the fact that these places were built, from the start, in the shadow of discriminatory policy.

Yet the loss does not mean the story ends. These parks persist as frameworks for understanding present debates about public space: who feels safe, who feels watched, who feels welcomed, and which neighborhoods are given the resources to host joy without having to justify it as an exception.

The stakes of telling these stories now

Why devote long attention to two parks that no longer operate? Because the conditions that produced them—segregation by policy, exclusion by custom, the racialization of “public” space—did not vanish cleanly. They evolved. The twenty-first century language is different. We talk about access, equity, belonging, safety, and “third places.” But the underlying question is remarkably consistent: who gets to relax without negotiation?

Joyland and Suburban Gardens provide a historical answer that is both inspiring and sobering. Inspiring, because they show Black communities building beauty and fun in a society intent on limiting both. Sobering, because they show how fragile those creations could be when they depended on narrow margins of capital and vulnerable land. The parks offer a counternarrative to the notion that Black life is defined solely by struggle; they demonstrate the centrality of pleasure, music, play, and romance. But they also reveal how quickly even joy can become contested when it takes up space.

The Smithsonian’s framing of Black recreational spaces as havens “free from the threat of humiliation or violence” is not a sentimental line; it is a reminder that leisure has been, for many Black Americans, a space where the threat of violence was part of the calculus. A child’s day at an amusement park should not require strategic thinking. In Jim Crow America, it often did. These parks reduced that burden for a time.

In the long arc of Black public life, Joyland and Suburban Gardens belong to a lineage that includes Black beaches, resort towns, picnic grounds, ballparks, and dance halls—places built because exclusion forced creation. That lineage matters not only as history but as a map of what communities can do when they decide that joy is not optional.

A closing scene, and the radicalism of the ordinary

Imagine the smallest unit of the story: a family, a date, a group of friends. In Bronzeville, a streetcar ride south, a turn onto Wabash, the sound of laughter leaking into the street. In Deanwood, the trip to the city’s edge, the sight of a pavilion, the sense that you have arrived somewhere built with you in mind. These were not merely escapes from the week. They were rehearsals for citizenship—experiences of being in public without apology.

That is why these parks matter to Black American history. They show that the struggle for equality was never only about the courtroom and the ballot box, as essential as those arenas are. It was also about the dance floor and the picnic bench, the pool and the midway, the right to buy a ticket and step through the gate without being told, explicitly or implicitly, that your presence spoiled someone else’s fun.

Joyland Park and Suburban Gardens were built to contradict that message. Even in their absence, they still do.