A reminder that when public institutions are left to decay, the people who step in to stop the bleeding will be praised for whatever works, condemned for whatever breaks the rules, and remembered—forever—because they made the crisis visible.

A reminder that when public institutions are left to decay, the people who step in to stop the bleeding will be praised for whatever works, condemned for whatever breaks the rules, and remembered—forever—because they made the crisis visible.

By KOLUMN Magazine

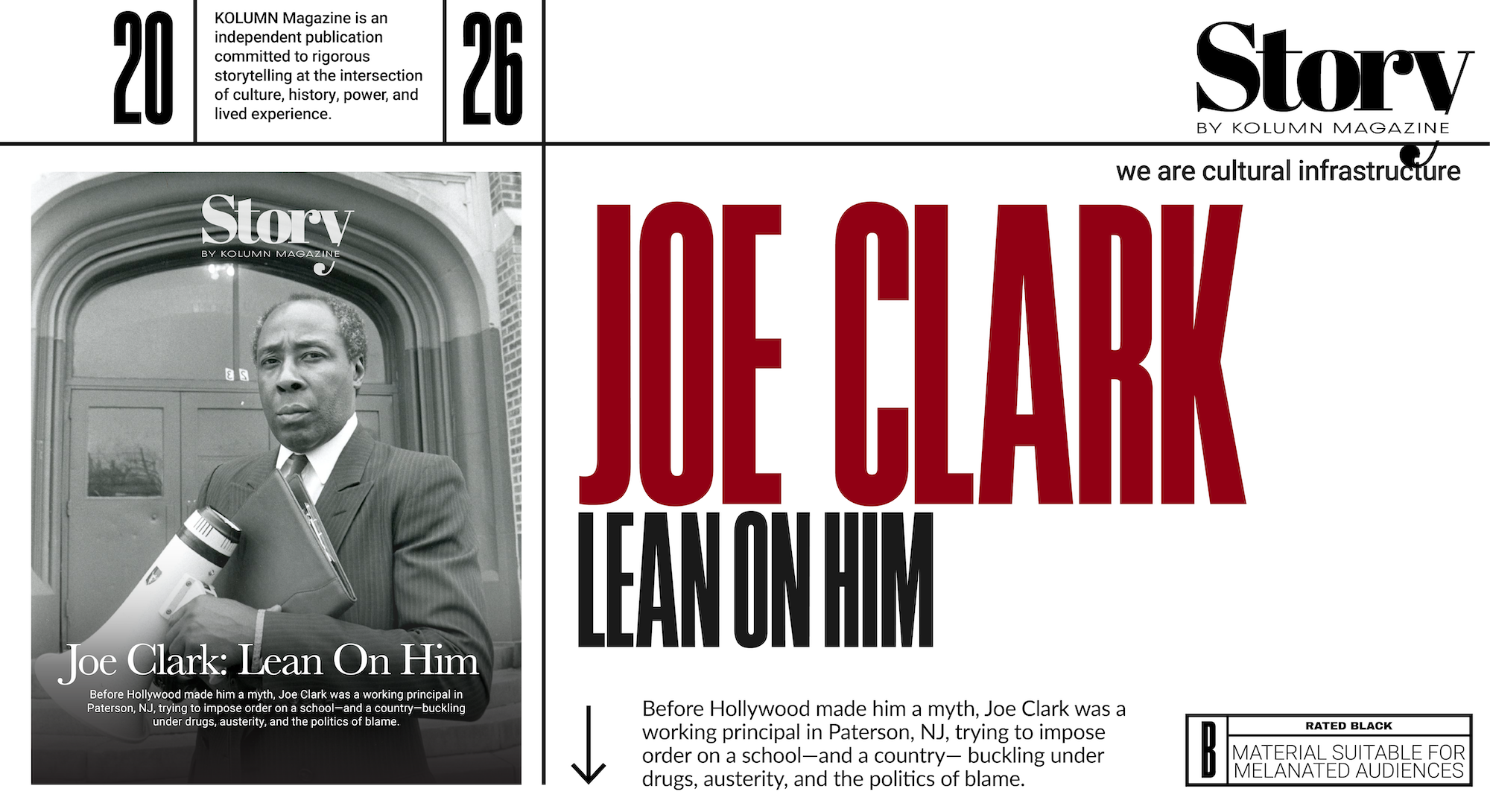

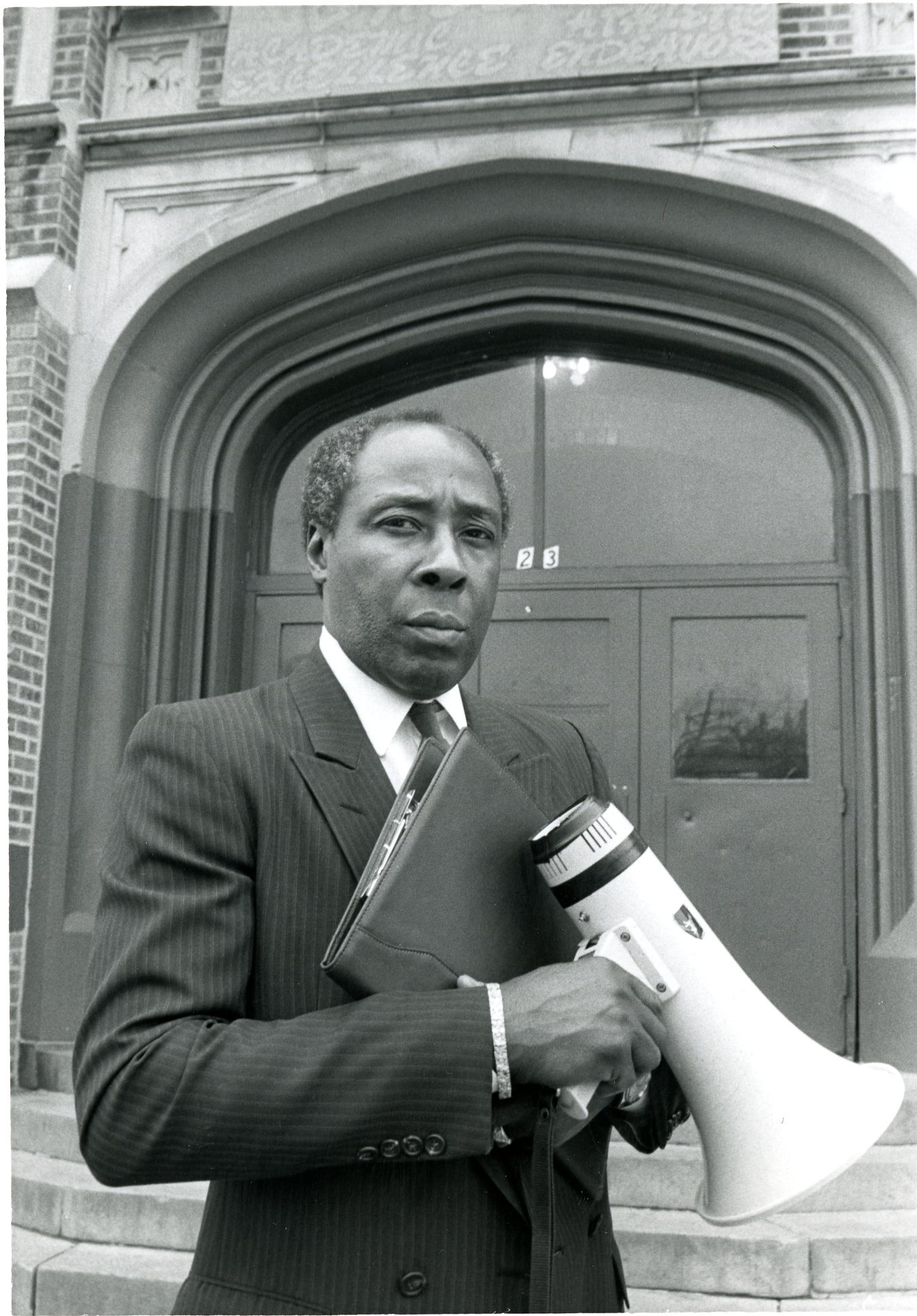

The first thing most people remember about Joe Louis Clark is not a policy, a curriculum, or a graduation statistic. It is an object: the bullhorn. Sometimes it is paired, in the public imagination, with a second prop—part metaphor, part menace—the baseball bat. The image is so durable that it has become shorthand for an entire theory of schooling: that a single forceful adult, unafraid of confrontation, can reorder a broken institution by sheer will.

But Joe Clark was never only an image. He was an educator shaped by the migration of Black families from the rural South to Northern cities, by the everyday volatility of urban schools in the late 20th century, and by the political stagecraft of the 1980s, when America increasingly treated public education as both scapegoat and salvation. He also became, in real time, a national argument—about due process, student rights, safety, exclusion, and whether discipline is a substitute for investment or a prerequisite for learning.

Clark’s fame is often narrated as a lightning strike: a tough principal arrives at a troubled high school in Paterson, New Jersey; he expels hundreds of students; the cameras show a city and a school at the edge; and the country—anxious about crime, drugs, and disorder—turns a working administrator into a folk character. But if you track the story more carefully, the arc is less sudden. It is built from a life that moved between worlds: the segregated South and industrial New Jersey; the discipline of the U.S. Army Reserve and the improvisational demands of public school leadership; the intimate realities of students’ lives and the distant expectations of policymakers and television producers.

Clark’s biography, like many American biographies, also exposes how celebrity rearranges meaning. What he did at Eastside High School—what he was praised for, what he was condemned for, what he was allowed to do, and what he was eventually forced to stop doing—cannot be separated from the era that watched him. The Reagan years offered a particular kind of stage: a national appetite for individual heroes who could “fix” public problems without demanding systemic repair. In that sense, Joe Clark did not just lead a school. He became a story Americans told themselves about what it takes to save one.

From Rochelle to Newark: The making of a disciplinarian

Joe Louis Clark was born in Rochelle, Georgia, in 1938. As a young child he moved with his family to Newark, New Jersey—part of the larger current of Black Southern migration that reshaped Northern cities in the mid-20th century and, by extension, their public institutions.

That migration story matters because Clark’s later public persona—unapologetic, combative, sometimes theatrical—was often reduced to temperament. Yet much of what he would argue, later in life, was about the fragility of Black opportunity in cities that had promised more than they delivered. Newark was not simply a new address; it was an education in how quickly a community can be blamed for conditions created by policy, labor markets, and segregationist design. Clark went on to earn degrees from what is now William Paterson University and from Seton Hall University. He also served in the U.S. Army Reserve, where he was a drill sergeant—an experience that offered both a style of authority and a vocabulary of order that would later define him in the public mind.

In the stories told about him, the drill-sergeant detail is often delivered as a punchline: of course he barked at teenagers; of course he believed in command presence; of course he treated the hallway like a parade ground. But drill-sergeant authority is not only volume. It is a theory of human behavior: that standards can be learned through repetition, that chaos can be replaced with routine, and that compliance is the gateway to performance.

Whether that theory belongs in schools is precisely what Clark’s career forced people to confront. And it is worth noting that even his critics—those who would later accuse him of violating students’ rights or abusing power—rarely disputed the underlying crisis he was responding to: schools in many American cities were struggling with violence, drugs, absenteeism, and the demoralization of educators who felt abandoned by the state. The disagreement was over method, and over the moral cost of method.

Clark began his professional life in education at the elementary level and moved through administrative roles. The work was not glamorous, and it was not designed for the kind of national attention he eventually received. But it put him close to the machinery of public schooling: the daily negotiation between family instability and academic expectations, between neighborhood pressures and institutional rules, between what adults want a school to represent and what young people experience it to be.

By the time Paterson called him to Eastside High, Clark was not a celebrity in search of a stage. He was an administrator with a reputation for confrontational order-making. The stage arrived anyway.

Eastside High: The emergency becomes a brand

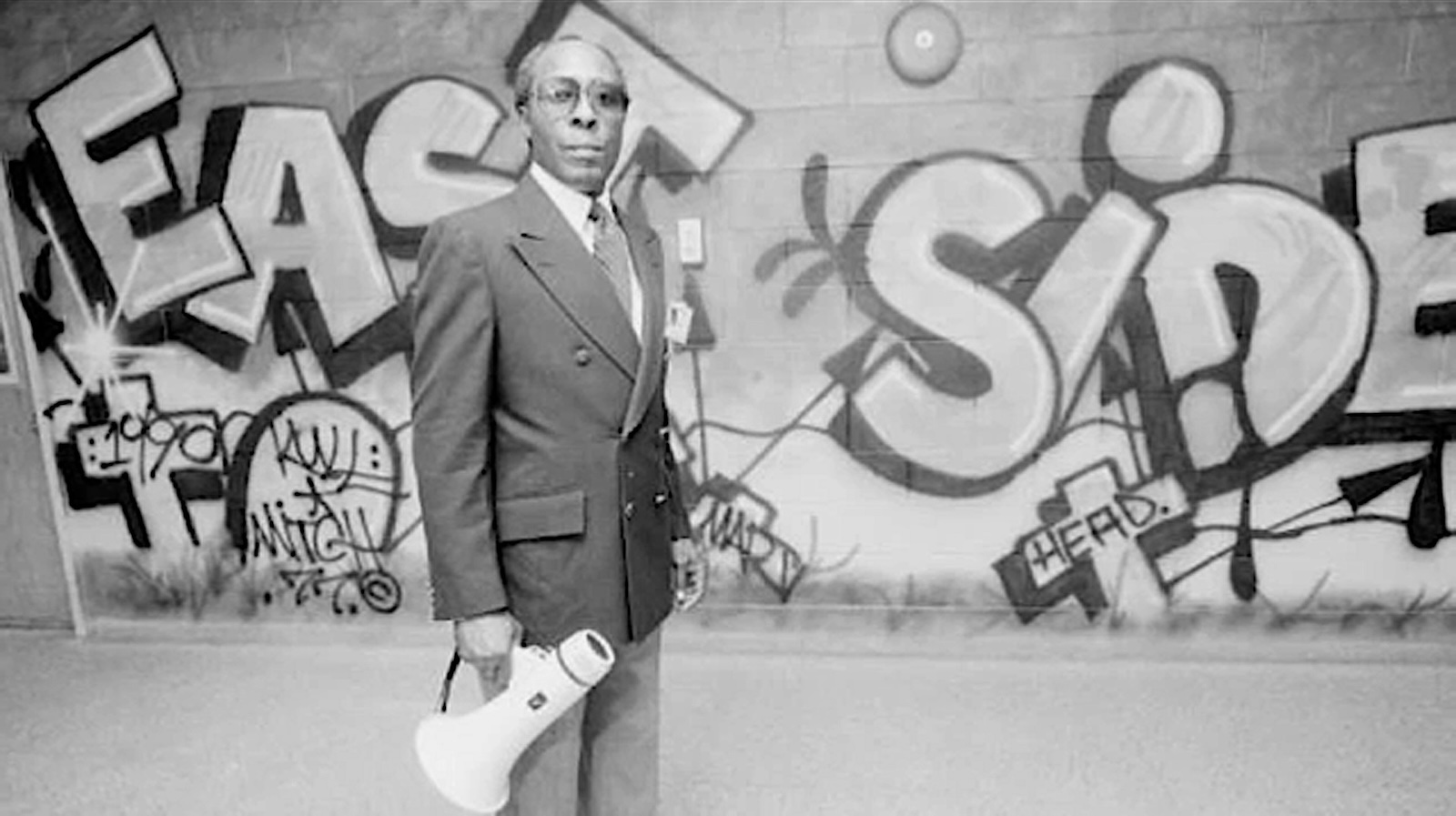

In 1982, Joe Clark was appointed principal of Eastside High School in Paterson. The building and its surrounding community had become symbols—locally and, soon enough, nationally—of what Americans feared about cities: violence, narcotics, and institutional decline. Paterson’s problems were not unique, but Eastside’s visibility became exceptional once Clark began acting like a man who understood that visibility could be weaponized.

Early in his tenure, Clark made the kind of move that becomes legend because it is legible: he removed hundreds of students from the building, described in many accounts as roughly 300 in a single day, targeting students identified as chronically disruptive, truant, or involved with drugs and violence. The act was framed by supporters as triage—an emergency measure to secure learning for those who wanted it—and by critics as abandonment, a bureaucratic cleansing that improved order by exporting the hardest cases to the street. .

Time magazine, which put Clark on its cover in 1988, captured the two-sidedness that would define him: a principal who “kicks up a storm” and who, in the telling, became a national proxy for “discipline in city schools.”

That cover mattered—not only because it made Clark famous, but because it made his fame official. Once a principal lands on a national magazine, he is no longer simply accountable to a superintendent or a school board. He becomes accountable to the story the country wants. And in the late 1980s, the country wanted a story in which disorder could be confronted without ambiguity.

Clark cultivated that story with an intuitive sense for performance. The bullhorn made him audible in crowded hallways; it also made him camera-ready. The bat—he insisted in various accounts—was not intended as a weapon but as a symbol, a way to dramatize stakes and choices. Yet symbols do not behave neutrally in institutions where power is already unequal. What one adult calls metaphor, a teenager may experience as threat.

The most consequential moment of Clark’s Eastside years may also be the most contested: the decision to chain or otherwise secure doors to keep intruders out—an act that triggered fire-code concerns and legal consequences. His defenders saw a leader prioritizing safety in a building they believed the system had left exposed. City officials and critics saw reckless disregard for basic safety law and the rights of the people inside.

Education Week reported on the legal and administrative actions surrounding Clark, including charges tied to fire-door compliance and the chaining of exits, quoting him using the kind of language that made him irresistible to both admirers and opponents—calling would-be intruders “mutants … rapists and murderers,” a phrase that reads as both alarm and dehumanization.

In an archive report, UPI described Clark settling contempt-related charges with commitments to observe the fire code—an episode that illustrates the recurring pattern of his career: he would push beyond institutional constraints, win public applause for boldness, then collide with legal frameworks designed to limit precisely that kind of unilateral power.

The debate Clark forced into the open: Safety, learning, and exclusion

Supporters of Joe Clark often speak about atmosphere: the feeling, after the purge, that hallways were calmer, that teachers could teach, that students who wanted to learn could move through the day without fear. Those claims are hard to dismiss because they map onto what many students and educators in struggling schools report as their first need: physical and psychological safety. Clark’s central proposition was that a school cannot educate until it controls its environment.

Critics did not necessarily deny the desire for safety; they contested the means, the legitimacy, and the downstream harm. The ACLU voice quoted in Time’s reporting warned that if every principal followed Clark’s approach, many students would simply be “thrown … into the street,” trading school disorder for social disorder—minimum-wage futures at best, incarceration at worst

This is not a secondary critique. It is the core policy question: when a school “improves” by exclusion, what has been improved—and for whom? If one group of students gains a functioning classroom because another group is removed, the school may be safer, but the community may be less safe. And the removed students—often older, often already marginalized—become somebody else’s emergency, or no one’s.

Education Week’s contemporaneous coverage captured the institutional anxiety around Clark’s methods. Officials debated whether he should be dismissed; supporters called him a “folk hero”; and the conflict itself became a kind of curriculum, teaching the country what it often prefers not to learn: that saving a school can mean choosing which children a school will claim as its responsibility.

Even the metrics were mixed, depending on what one measures and when. Time noted both the disciplinary successes and the difficulty of converting order into academic transformation at scale, emphasizing that academic triumphs can be more elusive than restored calm. Education Week, summarizing Time’s coverage, underscored that point: discipline was visible; learning gains were harder to secure and to verify.

This is where Joe Clark’s story becomes less about personality and more about structural limits. Urban public schools can be asked to do the work of multiple institutions: education, social services, mental health triage, violence prevention, and employment preparation. When the state withdraws resources and then demands results, principals are incentivized to manage appearances as much as outcomes. Clark understood that order looks like success on television. Whether it becomes success in students’ lives is a longer, harder project.

When politics came calling: Reagan-era hero-making

Joe Clark did not become famous in a vacuum. His rise occurred in a decade in which crime and drugs were framed as existential threats, and public institutions—especially urban ones—were portrayed as failing. It was also an era when political leaders frequently favored personal-responsibility narratives and high-visibility enforcement over long-term public investment.

Time’s issue framing and subsequent education-trade commentary show how quickly Clark became a symbol in a national argument, with prominent figures praising him even as “most educators” debated whether he “swings too hard.”

There were moments when Clark appeared to be on the verge of being absorbed into national politics, discussed as a possible Reagan administration figure—a development reported in period coverage about his legal controversies and national profile. The fascination was predictable: a Black principal embodying a discipline-forward solution made for powerful bipartisan optics, allowing leaders to praise “toughness” while sidestepping resource questions.

Yet Clark’s relationship with institutions of authority was never simple. He courted the spotlight but resisted constraints. He was willing to work with power so long as power did not attempt to manage him. That dynamic—public celebration paired with bureaucratic conflict—would repeat later in his career.

Hollywood’s Joe Clark: “Lean on Me” and the manufacture of a myth

In 1989, the story of Eastside High became a studio film: Lean on Me, directed by John G. Avildsen and starring Morgan Freeman as a fictionalized Clark. The movie was explicitly marketed as truth-adjacent—a “based on” story with the emotional architecture of a modern morality play.

The film succeeded not only because it dramatized real fears—drug-ridden hallways, endangered teachers, students left behind—but because it offered an ending Americans wanted: the charismatic principal’s methods, though controversial, produce a quantifiable win. The school passes the test. The state is kept at bay. The crowd chants for its leader.

But contemporaneous criticism, including from major newspapers and education observers, warned that the film’s mythmaking was not harmless. A Los Angeles Times commentary argued that the movie took “artistic liberty” and was not a fully true story, even as it acknowledged Clark’s real importance to many students.

Education Week published sharp skepticism about the cultural appetite for watching teenagers be humiliated or manhandled on screen while viewers would never tolerate such treatment for their own children—an indictment of how class and race shape the moral boundaries of “acceptable” discipline.

Those critiques point to an uncomfortable truth: Lean on Me helped normalize the idea that authoritarian discipline is not only effective but noble when applied to poor children in majority-Black schools. The film made Clark’s style legible as heroism, even to audiences who might have rejected the same approach in a suburban building.

Morgan Freeman, in later remarks reported through local coverage, described Clark as a “father figure” and “the best of the best” in education—an endorsement that reflects the affection the story can generate, particularly among those who read Clark as a protector.

Yet the deeper cultural impact may be that the movie narrowed the policy imagination. It trained viewers to search for the next Joe Clark—another singular personality—rather than to ask why so many schools were made to rely on singular personalities to survive at all.

The author of his own method: “Laying Down the Law”

The same year the film arrived, Clark’s strategy was codified in print. He co-authored a book, Laying Down the Law: Joe Clark’s Strategy for Saving Our Schools, which framed his approach as replicable guidance, not merely personal temperament. Library catalogs and bibliographic records list the book as a 1989 publication, associated directly with Eastside High and urban education case-study framing.

The existence of the book matters because it signaled a shift from local crisis management to national prescription. Clark’s argument—at least as it was popularly understood—was that schools needed authority restored, standards enforced, and adults empowered to remove chronic disruptors. He also argued that bureaucratic rules often protected dysfunction. Whether one agrees or not, that thesis became a staple of reform debates for decades.

It also created an additional ethical dimension: when a school leader profits—financially or reputationally—from crisis, who is being served by the narrative? Clark, like many public figures, operated at the intersection of mission and brand. He plainly believed he was doing what had to be done. But he also learned how to translate a school’s pain into a national platform.

After Eastside: Detention, discipline, and the question of limits

After leaving Eastside, Clark’s career did not settle into quiet retirement. He remained a public speaker and took on leadership roles that aligned with his identity as an enforcer. In 1995, he became director of the Essex County Detention House, a juvenile detention facility in Newark.

In 2002, he resigned amid scrutiny and censure tied to allegations about excessive force and punitive practices, including the reported use of restraints such as straitjackets and prolonged handcuffing, along with other restrictive measures. Coverage at the time, including wire-driven reporting and youth-justice trade coverage, described official reports condemning the use of restraints as punishment and detailing conflict with oversight bodies.

Clark’s defenders might argue that juvenile detention is a different ecosystem entirely, one built around coercion and safety. Critics would counter that the controversy demonstrated precisely why schools—and youth systems more broadly—should be wary of elevating leaders who equate control with care.

What this later chapter does, at minimum, is complicate any tidy hero narrative. It suggests that Clark’s style was not situationally adopted for Eastside’s emergency; it was a worldview. And worldviews have consequences when transplanted into institutions where the line between order and harm is thin.

Family and private life: Legacy beyond the hallways

Public narratives about Clark often reduce him to the job, but his family life offers another perspective on his values and the environment he cultivated at home. He was the father of elite track athletes—daughters Joetta Clark Diggs and Hazel Clark, among others—and his role as patriarch has been noted in sports-world remembrances, which emphasized his mentorship and the discipline associated with athletic excellence.

Those details do not erase the controversies; they add dimension. Many people who knew Clark privately describe him as devoted, demanding, and present—the same qualities that, publicly, could read as inspiring or intimidating depending on the recipient.

Clark died in late 2020 in Florida, with obituaries and national coverage recounting both his impact and the enduring controversy over his methods. The Washington Post described him as “bullhorn-bearing,” a man whose celebrity emerged from efforts to impose order and who remained a “lightning rod” in a long-running American debate about education.

What Joe Clark “accomplished,” and what he revealed

If you ask what Joe Clark accomplished, you will hear at least three different answers, each shaped by what the speaker believes a school is supposed to do.

One answer is immediate and operational: he restored a sense of control at Eastside High during a period of chaos, using highly visible tactics that signaled to students and adults that the building would no longer be governed by fear. That kind of accomplishment is often felt more than it is measured, and it is why some former students and community members remember him with real affection.

A second answer is political and cultural: he forced the country to pay attention to a school it would otherwise ignore, and he dragged an argument about discipline and urban education into national prime time. Time’s cover, Education Week’s sustained coverage, and the later film adaptation all indicate that Clark did not merely lead a school; he created a case study the nation consumed.

The third answer is more ambivalent: he demonstrated how easily “saving” a school can become synonymous with exclusion, and how quickly an adult’s authority can be celebrated even when it collides with legal rights, safety codes, or the dignity of young people. The very episodes that made him famous—mass removals, confrontations with boards, the chaining of doors—are also the episodes that raise hard questions about the ethics of power in public institutions.

In other words, Joe Clark’s accomplishments cannot be separated from the costs—and that is why his legacy endures. He remains useful to people arguing about schools today because his story can be deployed in multiple directions. For some, he is proof that “tough love” works. For others, he is proof that America prefers discipline theater to structural repair.

The lasting argument: Why his story still won’t settle

More than three decades after Lean on Me, it is tempting to treat Joe Clark as an artifact of a different era—an 1980s character with an 1980s solution. But many of the conditions that produced his fame have not disappeared: schools facing community violence, debates over student rights and exclusionary discipline, public frustration with low performance, and political incentives to elevate strongman narratives over complex policy.

Recent commentary revisiting the film and Clark’s era has pointed out how the “personal responsibility” message can obscure structural realities—economic disinvestment, punitive drug policy, and the broader civic abandonment of public schools. That critique is, in effect, an argument about narrative: when we romanticize the principal, we may ignore the system that made such romance necessary.

And yet the other side of the argument persists because it is also grounded in truth: children cannot learn in a building where adults are afraid, where classrooms are routinely disrupted, where a student’s day is shaped by the threat of violence. For communities that experienced those conditions, Clark’s insistence on order can feel like respect—an adult finally taking the school seriously enough to defend it.

The mature conclusion is not that Clark was simply right or simply wrong. It is that he embodied a set of tradeoffs that American education keeps postponing. If we want schools that do not rely on bullhorns, we need systems that do not force principals to become crisis performers. If we want discipline that does not become exclusion, we need credible alternatives for students who are struggling—mental health services, wraparound supports, restorative infrastructure that is more than a slogan, and pathways that do not treat removal as the default.

Joe Clark’s life, in the end, is less a parable about a single man than a mirror held up to a country that wants schools to be sanctuaries—but too often funds them like afterthoughts, then celebrates the rare leader willing to rule the afterthought by force.

He was an educator, yes. He was also a signal flare: a reminder that when public institutions are left to decay, the people who step in to stop the bleeding will be praised for whatever works, condemned for whatever breaks the rules, and remembered—forever—because they made the crisis visible.