To tell this story well is not to turn Chicago into a morality play; it is to insist on specificity.

To tell this story well is not to turn Chicago into a morality play; it is to insist on specificity.

By KOLUMN Magazine

Chicago 1917-1919

Chicago is a city that has always told its story in motion: stockyards and rail spurs, lake winds and factory whistles, parades and picket lines. In the popular imagination, the city’s racial history is often narrated in a familiar arc—southern migrants arriving by train during the Great Migration, overcrowding in the Black Belt, mounting tension in the labor market, and then the shock of the 1919 race riot after Eugene Williams drowned at the 29th Street beach. But that arc can become too clean, too cinematic, too dependent on a single inciting incident.

For many Black Chicagoans, the decisive warning came earlier and sounded different. It arrived as a concussive crack from a front porch, as shattered glass in a bedroom, as a crater in a front walk that had held a child’s chalk drawings the day before. From 1917 through 1919, a campaign of bombings—described in contemporary accounts as “race bombs”—struck Black homes and, by design, Black ambitions. These were not the bombs of foreign battlefields, though they unfolded in the shadow of World War I; they were domestic explosives used to defend a local order. They were aimed at a very specific problem as white Chicago defined it: Black families attempting to move beyond the narrow strip of overcrowded blocks that the city had informally designated as the Black Belt.

The bombings mattered not only because they maimed property and killed people, but because they represented a kind of governance—extralegal, deniable, and effective. They clarified what “segregation” meant in a northern metropolis where the most explicit Jim Crow statutes did not define daily life, yet where racial boundaries were heavily policed by custom, market power, intimidation, and violence. They also revealed something that would become a recurring theme in Chicago’s twentieth-century racial history: the distance between what Black residents could plainly see and what the city’s institutions were willing to name.

A public-facing Chicago could acknowledge “trouble,” “disturbances,” “clashes.” But a quieter Chicago—lived in kitchens and hallways—recognized the pattern: bombs were being thrown at Black homes, repeatedly, with little fear of consequence. WTTW’s summary of the period captures the shape of it plainly, noting that “from 1917 through 1919, some two dozen black homes in Chicago were bombed,” that a six-year-old girl named Garnetta Ellis was killed in one of the attacks, and that none of the bombings were ever solved by police.

If the riot of 1919 was the week when the whole city could not look away, the bombings of 1917–1919 were the years when many people did.

A city remade by the Great Migration—and trapped by housing

Between 1910 and 1920, Chicago’s Black population surged dramatically, more than doubling in that decade, propelled by the promise of wartime jobs and the push of racial terror in the South. The Great Migration was not merely a demographic shift; it was a reordering of labor, politics, religion, and cultural life. Bronzeville—though the name itself would take firmer hold later—became both a destination and a crucible. New arrivals built institutions quickly: churches and social clubs, newspapers, fraternal orders, small businesses, and professional networks that helped turn the South Side into one of the most significant Black urban communities in the country.

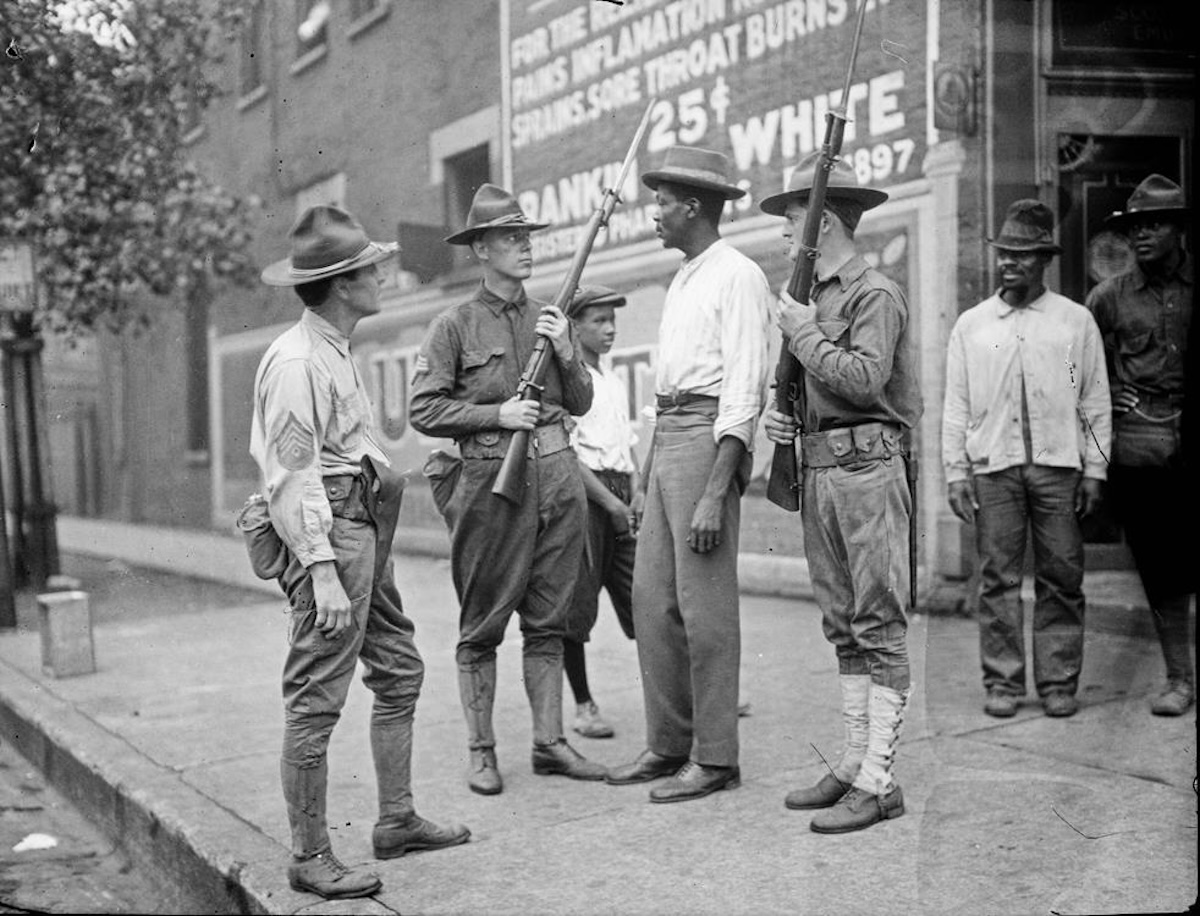

But housing was the bottleneck. Chicago’s Black Belt was narrow, crowded, and increasingly exploited. As more migrants arrived, the pressure intensified. Landlords subdivided apartments, raised rents, and packed more people into buildings that were already strained. The Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project, summarizing the pre-riot environment, describes a pattern that mattered as much as the riots themselves: when Black residents sought housing outside the Black Belt, many whites responded with neighborhood associations and intimidation. In that telling, homemade bombs were part of the enforcement mechanism—an escalatory tool used when persuasion and market pressure were not enough.

The bombings were not only expressions of rage; they were instruments of spatial control. The point was to make the act of crossing the color line feel costly, frightening, and ultimately irrational. If a family could be convinced that moving into a contested area might bring a bomb to the porch, then segregation could reproduce itself without requiring formal law.

This was segregation as a collaborative project between the respectable and the violent, between the committee meeting and the night raid. The language of “property values” and “neighborhood protection” often served as the respectable face of the same objective. Chicago Magazine, describing the period leading into 1919, cites property-owner rhetoric that framed Black neighbors as a kind of damage. It also underscores the terror campaign’s scale: “In the two years leading up to the riot, bombs were thrown at two dozen homes of black Chicagoans,” and police “solved none of these crimes.”

If you want to understand why the bombings proliferated, you have to understand how intensely contested the idea of a “home” had become. Housing was not simply shelter. It was the gateway to better schools, to stable wealth, to political leverage, to a sense of permanence in a city that still treated Black residents as temporary labor. And for the growing Black middle class—professionals, entrepreneurs, ministers, skilled workers—housing was also a statement: a claim to the rights of the city.

That claim was precisely what the bombs were meant to dispute.

The mechanics of “race bombings”: Deniable terror, public message

Bombings are often imagined as acts of spectacle. In this Chicago story, they were also acts of repetition. A single explosion could be dismissed as an isolated outrage, a mystery, a quarrel. But repeated bombings—across multiple addresses, concentrated in particular border areas, occurring with enough frequency to become a community expectation—functioned as a system.

A 2019 legal education compilation produced by the Illinois State Bar Association, drawing on historical documentation around the riot era, describes “fifty-eight bombings of homes” between July 1, 1917, and March 11, 1921, with a significant concentration in a bounded South Side area. It also notes that “during the six weeks immediately preceding the Chicago race riot, there were seven racial bombings.” Even if a broader tally extends beyond 1919, the numbers underscore what Black Chicagoans experienced in 1917–1919: bombings were not aberrations. They were becoming routine.

The routine nature of the violence created an ambient threat. It also allowed perpetrators to rely on a familiar American advantage: plausible deniability. Bombings could be framed as unknown assailants, “someone” throwing something, a crime without a culprit. And because the violence was directed at Black families attempting to move, it could be absorbed into the same social logic that blamed victims for their own vulnerability: why did they try to live there?

But the message was not subtle. Bombs are arguments delivered in metal fragments. They communicated that the “color line” was not just social; it was explosive.

The bombings also carried a cruel efficiency. They required far fewer people than a mob attack. They did not demand the sustained public frenzy of a riot. They could be executed at night, quickly, and then folded into an investigative process that often went nowhere. They made it possible for segregationists to enforce boundaries even when many white residents did not personally participate in violence, or even when some quietly disapproved. In effect, the bombers and those who shielded them made terror do the work of consensus.

A child killed: Garnetta Ellis and the human cost of the “message”

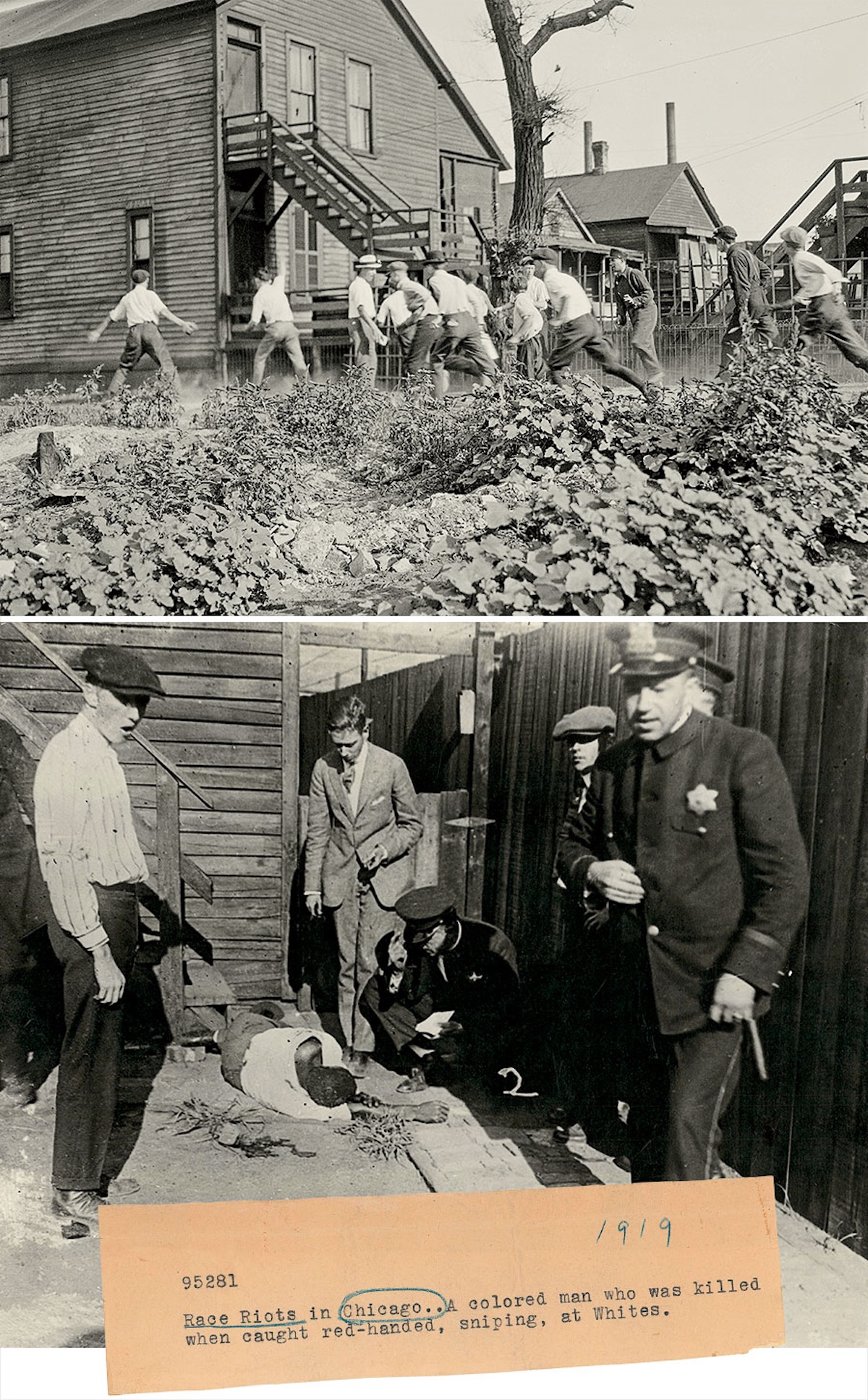

The story of these bombings can be told in numbers, but it should not be told only that way. The campaign’s cruelty becomes clearest when it reaches into the domestic sphere and kills a child.

Garnetta Ellis was six years old when she became one of the most haunting names in this period. The Northwestern University-based “Homicide in Chicago 1870–1930” database records her as the victim of a bomb explosion at 3365 Indiana Avenue, noting that the bomb was thrown by an unknown person and that arrest was recommended by the coroner. The database entry is blunt, almost bureaucratic, and that bluntness is part of what makes it chilling: a child dies, an “unknown person” is responsible, the system marks the death, and the city continues.

Her death matters because it reveals the bombings’ nature. These were not merely “property crimes.” They were assaults on life, and they were waged in spaces where life is supposed to be most protected—homes where families slept, where children played, where meals were cooked, where the idea of safety was supposed to reside. When a bomb kills a six-year-old, the message is no longer only about keeping a neighborhood “white.” It is also about what Black families are expected to endure for daring to claim ordinary stability.

Chicago Magazine’s account of the pre-riot period also points to Ellis’s death as emblematic of the bombings’ stakes, noting that she died in one explosion amid the unsolved wave of attacks.

The deeper journalistic question is not only who threw the bomb, but what social arrangement made it plausible that a child’s death would not provoke a full civic crisis. The answer lies in the relationship between public sympathy, policing priorities, and the racialized assumptions of whose safety counts as a city’s concern.

The targets: Pioneers, professionals, and the problem of Black aspiration

Not every Black family could afford to push against the housing boundary. Those who did were often the people with enough savings, credit, and social capital to purchase property or secure leases in contested neighborhoods. That fact shaped the violence. Bombings often targeted not only working-class renters but also the visible symbols of Black advancement: professionals, entrepreneurs, and real estate figures who helped facilitate Black housing mobility.

Jesse Binga’s experience illustrates the pattern and its symbolic charge. Binga, a prominent Black banker and real estate entrepreneur, became a lightning rod. Historical summaries of the riot era frequently note repeated attacks on his home. The Illinois State Bar Association compilation references the “repeated bombing” of Binga’s home as part of the larger pre-riot bombing landscape. A separate profile of Binga’s life and significance notes that his home was bombed multiple times in 1919 in an attempt to force him and his family out of a white neighborhood.

Binga’s targeting made a kind of strategic sense to segregationists. If you terrorize a prominent figure—someone whose name is known, whose business is connected to property and finance—you do not only punish that individual. You also warn others who might follow. You attempt to sever the mechanisms that make Black mobility possible: the banker who extends credit, the realtor who finds listings, the network that connects migrants to housing beyond overcrowded blocks.

In this way, the bombings were designed to interrupt not just individual lives but an ecosystem. They were aimed at the infrastructure of Black settlement.

The WBEZ “Curious City” project on Chicago’s 1919 Red Summer history—presented in part through reporting and historical interpretation—also emphasizes that intimidation and bombings targeted Black families who moved into predominantly white neighborhoods, and that the near-60 bombings in the period were met with only two arrests. Even allowing for the broader range of years, the policing pattern is the point: terror was persistent; accountability was rare.

Police inaction as policy: What it means when terror goes unsolved

In many American stories of racial terror, the most consequential actor is not the masked vigilante but the uniformed institution that chooses not to act. Chicago’s 1917–1919 bombings fit that pattern.

The Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project describes bombings of Black homes and adds a critical detail: police “failed to make any arrests, despite numerous witnesses.” That is not merely a failure of detection; it is a failure of will. When a crime is visible, discussed, and recurrent, and the city’s enforcement apparatus cannot—or will not—produce meaningful outcomes, the message travels in two directions at once. The bomb tells Black families they are unwelcome. The non-arrest tells perpetrators they are safe.

The Illinois State Bar Association compilation, drawing from the commission-era documentation, makes the structural nature of this failure even clearer. It notes that in some cases Black residents were warned of the exact dates they would be bombed; sometimes policemen were on duty at the targeted locations; and yet only two arrests were made, with one person released quickly and the other never brought to trial. implication is stark: even foreknowledge and presence did not translate into protection.

This is where journalism has to resist the temptation to describe these events as simply “unsolved.” “Unsolved” suggests mystery. But for the people living through it, the pattern likely felt less mysterious than inevitable. What appears as a string of puzzles in a police file can function, socially, as a stable arrangement: Black residents absorb the risk, white bombers absorb the impunity, and the city preserves the housing boundary.

In this light, policing becomes part of the mechanism by which segregation hardens. You do not need a written ordinance if you have a predictable sequence of violence and indifference.

Underreporting and framing: When newspapers shrink an explosion

The story also raises uncomfortable questions about media. How does a city narrate a bombing campaign against Black residents? Does it call it terrorism, lawlessness, a crisis? Or does it reduce it to a few lines and move on?

The Illinois State Bar Association compilation, quoting from commission-era findings about coverage, argues that many bombings were “underreported,” that news articles often ended with some version of “the police are investigating,” and that newspapers failed to condemn bombings as crime except in the case where a child was killed. Even without adopting every phrasing of that critique, the underlying point stands: what a city emphasizes and what it compresses affects public urgency.

Underreporting also works as a form of insulation. If bombings are reported as isolated events rather than a pattern, white Chicagoans who do not live near the boundary can imagine the violence is incidental. They can avoid the conclusion that their city is hosting an organized terror campaign. And officials can avoid the pressure that comes when a problem is widely recognized as systemic rather than episodic.

This is one reason the later Chicago Commission on Race Relations report, The Negro in Chicago, became so important: it attempted to treat the violence, including housing conflict, as a social phenomenon rather than a series of accidents. (The Newberry Library’s classroom materials on the riot era explicitly reference bombings and beatings as part of the background conditions as Black Chicagoans tried to expand beyond the Black Belt.

If the bombs were a message about where Black people could live, then the city’s muted response—police and press alike—was another message about whose suffering merited sustained attention.

1919: The riot as eruption, not origin

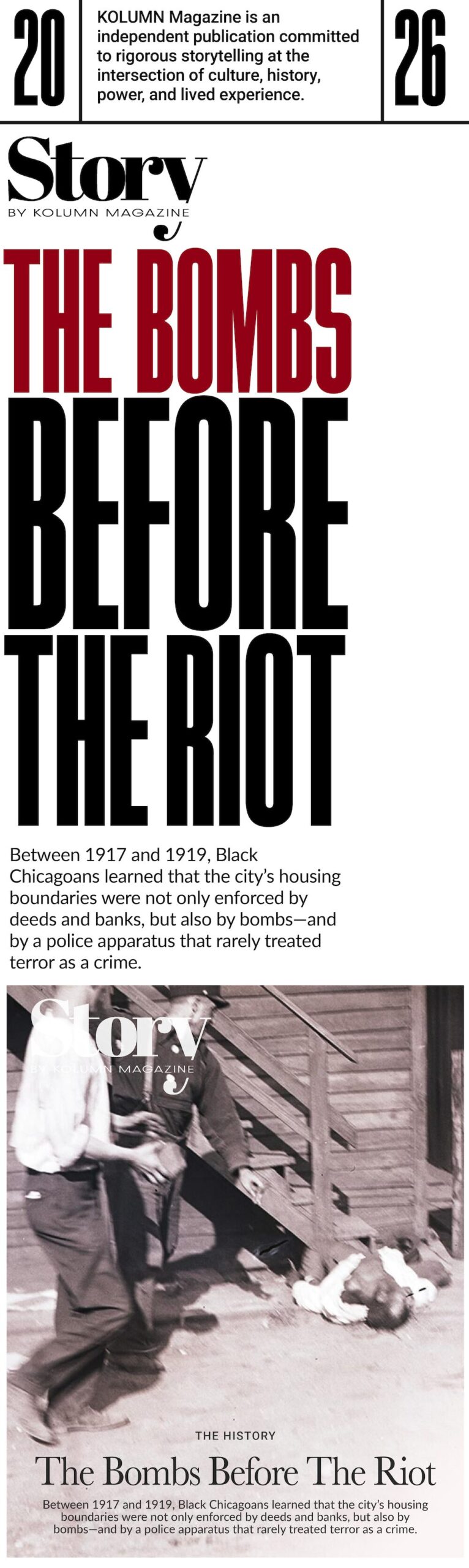

By the time Eugene Williams drowned in July 1919, Chicago had already been practicing violence. That does not minimize the riot’s brutality; it clarifies it. The riot was an eruption of forces long building: labor competition, wartime anxieties, ethnic gang enforcement of boundaries, political failures, and a deepening sense among Black veterans and civilians that self-defense might be the only defense available.

But the bombings matter here because they show the riot did not begin with the first rock thrown at the beach. The city had been “testing” the boundary with explosives. The riot, in that sense, can be understood as the moment when the logic of boundary enforcement moved from targeted domestic terror to mass public violence.

WTTW’s overview places the bombing wave in direct proximity to the riot narrative, suggesting the attacks helped form the atmosphere that made 1919 combustible: bombings, mob attacks reported in early summer, then the beach incident, then the week of citywide violence.

That sequencing is important. It means the riot did not create the city’s racial crisis; it exposed it. It also means the bombings were not merely prelude. They were part of the same phenomenon: a contest over Black presence, Black mobility, and Black belonging in a modern industrial city.

Why bombs? The logic of terror in a “modern” city

It is tempting to ask why a northern city—so often mythologized as freer than the South—would produce this kind of tactic. But that question itself can rest on a flawed assumption: that modernity and industrial progress naturally reduce racial terror. Chicago’s case suggests the opposite. Modernity can provide new tools for old hierarchies.

Bombs were, in a grim sense, a “modern” method. They offered efficiency and distance. They allowed perpetrators to strike without direct confrontation and then disappear. They could be deployed to punish a family, a block, a symbolic figure, without assembling a crowd.

They also fit the new urban rhythms. In dense neighborhoods, an explosion reverberates beyond its immediate target. It becomes neighborhood knowledge fast. It spreads fear faster than a private threat letter could. And it requires the city to respond—police cars, investigators, reporters—meaning the state is constantly invited to choose whether to treat the violence as a true emergency.

In Chicago, that choice repeatedly landed on minimization.

The commission-era findings quoted in the ISBA materials suggest bombings were “systematically planned,” with some white residents withdrawing from “protective organizations” out of fear of responsibility, while associations denied involvement and emphasized “legitimate methods” like foreclosures and refusal to deal with Black residents. That split—between overt violence and “legitimate” market exclusion—points to a broader truth: the color line was protected by both the criminal and the legalistic. The bombings were one end of a spectrum, with restrictive practices on the other.

This spectrum matters because it prevents us from isolating “bad actors” as the whole story. The bomb thrower may have been a few individuals, but the overall effect—Black confinement—required a broader set of cooperating behaviors: lenders denying mortgages, realtors steering clients, owners refusing sales, neighborhood groups applying pressure, institutions failing to prosecute.

Bombs were not the entire system. They were the system’s enforcement arm.

The long afterlife of the bombing years

When historians and residents talk about Chicago’s segregation, they often point to later decades: restrictive covenants, redlining, public housing policy, expressway placement, and the gradual hardening of boundaries that became some of the most entrenched in the nation. But a key aspect of the 1917–1919 bombings is that they help explain why those later tools found such fertile ground.

Terror teaches geography. It trains families to understand certain streets as thresholds and certain neighborhoods as hostile terrain. It teaches children which blocks are safe and which are not. It also teaches institutions what they can get away with. If bombings can occur repeatedly without meaningful prosecution, then less dramatic forms of exclusion—paperwork, policy, financial discrimination—can be implemented with confidence that the broader racial order will hold.

This is why the bombings are not a footnote to the 1919 riot but part of the riot’s architecture. They demonstrate that segregation was not simply an “outcome” of population change; it was an achievement—one built through intimidation and sustained through institutional choices.

The Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project’s framing is blunt and, in that bluntness, clarifying: white violence, including bombings, was used as Black residents sought to move beyond the Black Belt; police often did not arrest anyone; and this unfolded within a national season of racial violence that came to be called the Red Summer. The national context matters because it reminds us Chicago was not uniquely violent; it was part of a broader American moment when Black postwar assertion met white backlash.

The National Archives’ overview of the Red Summer era situates the period within the Great Migration and the persistence of racial violence, emphasizing how the early twentieth century’s transformations were accompanied by brutal resistance. Chicago’s bombings belong to that resistance.

What a modern city owes its own history

A century later, the bombings of 1917–1919 can be difficult to hold in mind, partly because they resist tidy categorization. They were not a single mass casualty event that forced immediate national reckoning. They were dispersed, local, and often recorded in fragments—newspaper briefs, coroner recommendations, later commission summaries, oral histories. Their very structure aided forgetting.

But forgetting is itself a political outcome. When a bombing campaign against Black homes becomes a vague prelude rather than a central narrative, it becomes easier to treat segregation as an unfortunate “pattern” rather than something that was actively produced. It becomes easier to talk about “neighborhood change” without naming the coercion that kept neighborhoods from changing. It becomes easier to describe modern Chicago’s racial map as if it were the natural shadow of economics rather than the product of contested power.

The bombings also complicate a comforting American storyline: that the North was simply a refuge from Southern racial violence. Chicago was a refuge in some respects—jobs, institutions, relative political opportunity—but it was also a laboratory for a different form of racial containment. The violence was not identical to the South’s, but it was not a contradiction of northern modernity either. It was one of its tools.

To tell this story well is not to turn Chicago into a morality play; it is to insist on specificity. A bomb on a porch is not an abstraction. A six-year-old girl killed by an explosive is not an anecdote. A pattern of dozens of attacks, met with near-total impunity, is not a mystery; it is a civic decision, even when no single official signs their name to it.

And that is the final, uneasy lesson of the 1917–1919 bombings: terror can function as policy when policy refuses to name terror.