By KOLUMN Magazine

The game Americans learned not to see

Every era has a catalog of amusements it later pretends not to recognize. Some are merely dated. Others are indictments: proof that a culture can turn cruelty into leisure, and leisure into a lesson. Among the starkest examples in the United States is a late-19th-century carnival attraction most commonly remembered as “African Dodger,” also advertised under titles that used racist slurs, including “Hit the Coon” and “Hit the Nigger Baby.” The names were not incidental marketing flourishes; they were the premise, the punchline, the instruction manual. The game reduced a Black person—often a Black man hired for the role—to a target whose dignity was meant to be disposable and whose injuries were treated as entertainment.

Because the slurs are part of the historical record, this article names the game once, explicitly, for accuracy. After that, it uses “African Dodger” as a descriptor while remaining clear about what those other names signaled: a social permission slip for public aggression. The archival trail is unambiguous that “African Dodger” was not an obscure prank tucked into the darker corners of American life. It appeared at resorts, fairs, amusement parks, and traveling carnivals; it persisted into the 20th century; and it was discussed in newspapers and popular culture as though it belonged to the normal inventory of American fun.

The game’s core mechanics were simple and, in their simplicity, revealing. A painted canvas—often a plantation scene, according to museum documentation—featured a hole cut for a human head. A Black “dodger” placed his head through that opening. White patrons paid for throws, commonly balls or eggs, sometimes harder objects, and won prizes for a direct hit. The “dodger” attempted to jerk his head away at the last moment, a frantic choreography that transformed self-protection into performance. The laughter belonged to the crowd; the risk belonged to the worker.

To understand why this existed—and why it could be described, advertised, and remembered as a diversion—you have to place it in the ecosystem that built it: Reconstruction’s collapse, the tightening grip of Jim Crow, the popularity of blackface minstrelsy and its caricatures, the mainstreaming of pseudoscientific racial hierarchy, and the mass-market economy that converted stereotypes into consumer goods. African Dodger wasn’t a glitch in the culture. It was a product of it.

A spectacle built from a hole in a canvas

Historians and curators who study racist objects often emphasize how mundane the violence could look in its own time. The booth was a booth. The barker’s patter was the barker’s patter. The prizes were the familiar bric-a-brac of turn-of-the-century popular entertainment. That sense of normalcy is part of what makes the game so historically important: it shows how white supremacy did not only operate through law and terror, but through habits and jokes and the low-stakes rituals of a day at the fair.

The Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia—one of the most frequently cited institutions documenting the game—describes “Hit the Coon” and “African Dodger” as a brutal cousin to related attractions that dumped a Black person into water when a target was struck. The museum notes that the booth often used a plantation scene and that prizes were awarded for a direct hit. It also documents commercialization around the practice: as early as 1878, one New York company offered painted “Negro Head Canvases” and wooden “Negro Heads,” suggesting that live targets were sometimes replaced by objects, but also that the market for the imagery—and the pleasure of aiming at it—was robust.

That commercialization matters. It means the game was not simply a spontaneous expression of prejudice, but something organized, priced, staffed, and supplied. Somebody built the canvas. Somebody secured the balls, the eggs, the prizes. Somebody hired the “dodger” and decided what was an acceptable level of risk. Somebody counted the money. Violence here was not only social; it was economic.

A telling detail in a scholarly article on representational violence against Black children is the way such games made aggression look legitimate by framing it as play. The article, quoting a Jim Crow Museum film resource, summarizes the logic: these attractions “highlighted and exploited” hostility toward Black people, presenting African Americans as “willing victims,” normalizing the idea that unprovoked violence was simply part of the social order. Even when the “target” was not a person but a model or picture, the message remained that Blackness was an acceptable object of attack.

The booth, in other words, was a kind of informal classroom. It trained participants in a bodily understanding of racial hierarchy: who could be hit, who could be laughed at, who could be paid to endure, who could pay to harm.

The labor of being the target

One of the enduring questions around African Dodger is also one of the most ethically delicate: why would anyone agree to be the “dodger”? The question is often asked as though it’s a puzzle, but it becomes less mysterious when you take seriously the labor market constraints of the era. Jim Crow was not just a collection of prejudices; it was an architecture of limited options. Many Black workers were boxed into exploitative employment, excluded from stable wages, and subject to threats that extended beyond the workplace. In that context, dangerous work was often not a choice between safety and risk, but a choice between risk and hunger.

The Jim Crow Museum’s discussion of the game explicitly frames it inside a society saturated with messages—religious, political, and “scientific”—that asserted Black inferiority and thus rationalized inhumane treatment. When a culture widely accepts that a group is less evolved, less sensitive to pain, or less worthy of protection, it becomes easier to build businesses around their humiliation.

But exploitation alone does not tell the entire story, because the “dodger” also had to perform. He was expected to move in a way that made the throws look exciting. He had to be present enough to be hittable, quick enough to keep the game going, and compliant enough not to disrupt the booth’s smooth functioning. That performance layer turns the attraction into something more than a battering ritual; it becomes a theater of control. The target is alive, and his aliveness is part of the entertainment, but only so long as it is constrained.

In practice, the line between “game” and assault was thin. The very premise encouraged escalation. A ball thrown softly might miss; a ball thrown hard might win. If prizes rewarded impact, then impact became the goal. Later reporting and archival references describe instances where participants brought heavier, more dangerous objects. Even without those escalations, repeated hits to the head are not benign. They are concussions, broken teeth, fractured bones, injuries that were easily dismissed because the injured party was doing the job the game required him to do.

When you encounter descriptions of African Dodger in institutional collections, a pattern emerges: the victim is rarely named. The booth’s operator is rarely named. The fair is named; the town is named; the sensation is named. But the person absorbing the harm is often treated as a replaceable part. That erasure is itself part of the historical violence.

Evidence in the archive: When the booth appears in public life

For an attraction so brutal, African Dodger’s paper trail can be startlingly casual. It shows up in lists of amusements. It is mentioned the way one might mention a carousel. That casualness is precisely why the game is historically useful: it tells you what a community assumed was normal.

A 2005 scholarly article about recreational outings among Philadelphia African Americans offers one of the clearest glimpses of the game’s presence near a major urban center. Discussing Gloucester City, New Jersey, the author notes that in the summer of 1888 the mayor ordered the closing of a beachfront “African Dodger” attraction and fined its proprietors for “disorderly and insulting conduct.” The author adds a blunt description of the booth’s operation—patrons attempting to hurl a ball at the head of a live African American positioned as the “bulls-eye”—and remarks that it remained a “common, blatantly racist attraction” into the twentieth century.

That single passage does several things at once. It establishes that the attraction existed in the 19th century and did so in a context that included Black leisure travelers. It suggests that local officials could recognize the booth as disruptive or insulting, even if their motivations were complex or inconsistent. And it reminds us that “closing” one attraction did not mean the logic of the attraction disappeared; it simply moved, adapted, or resurfaced elsewhere.

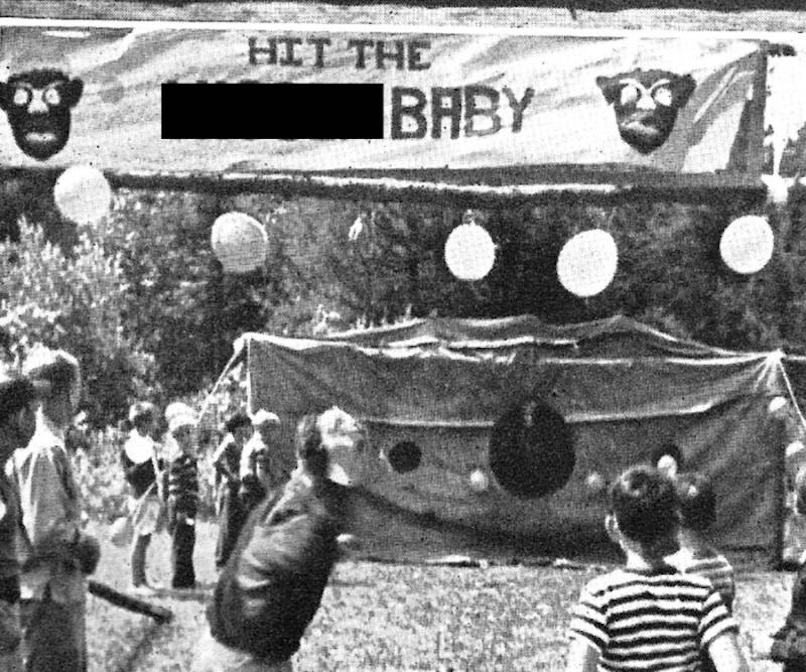

A century later, fact-checking documentation surrounding a 1942 YMCA camp brochure shows how long these themes persisted in American institutions that liked to imagine themselves wholesome. PolitiFact’s review of the brochure describes the game by its mechanics—three throws with a ball or egg at a target sometimes pictured, sometimes a real person—and notes that the brochure is preserved and discussed in museum and archival contexts. The point is not simply that the game existed, but that it existed in spaces dedicated to youth, recreation, and “character.”

If the fairground booth represents one part of the story, the camp brochure represents another: the normalization of racial aggression as a kind of playful training, something children could do, laugh at, and remember nostalgically.

The American amusement economy and the politics of “fun”

African Dodger sat at the intersection of two major transformations: the growth of a mass entertainment economy and the retrenchment of racial hierarchy after Reconstruction. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, commercial amusements proliferated. Resorts and parks marketed themselves as destinations for working people seeking a break from industrial labor and crowded cities. At the same time, American public life hardened around segregation and racial violence.

In that setting, games like African Dodger performed a dual function. Economically, they were cheap and profitable: the booth required minimal equipment, offered low-cost prizes, and could generate a steady stream of customers. Socially, they offered white patrons something more than distraction. They offered what scholars of race and class have called a wage that is not paid in dollars: the reassurance of status. A white laborer and a white shopkeeper could both step up to the same booth and purchase the same permission to strike. The act itself—throwing, aiming, winning—turned racial domination into an accessible pleasure.

The Salon essay on racist games captures how embedded this logic was. It places African Dodger within a broader culture where simulated violence against Black people was entertainment and where that entertainment both reflected and reinforced a world of real lynching and legal discrimination. It also notes how newspapers could mention the game among other attractions and how “dodgers” became newsworthy largely when injured.

If you are searching for a single “reason” the game was popular, you will miss the point. It was popular because it fit the era’s commercial incentives and moral assumptions. It made racism participatory. It let ordinary people rehearse a hierarchy with their hands.

From human target to “safer” spectacle: Adaptation, not absolution

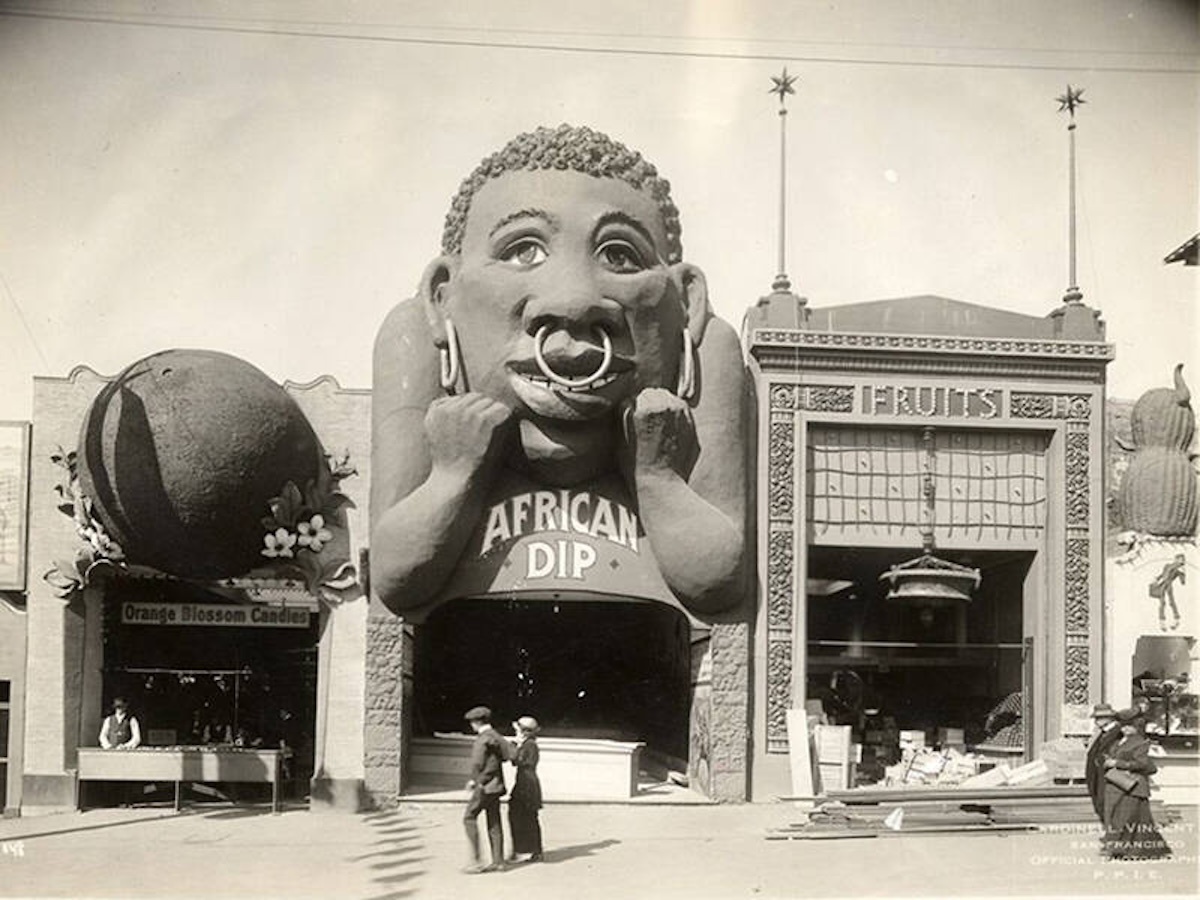

One of the most revealing features of racist entertainment is how it adapts when challenged. When a practice becomes controversial or illegal, it often mutates rather than disappears. The Jim Crow Museum describes related attractions—sometimes called “African Dip” or “Coon Dip” in period language—that used a target mechanism to dump a Black person into water. In this version, the crowd still paid to inflict humiliation; the violence was framed as less physically injurious than repeated blows to the head.

The “safer” iteration is still a lesson: reform is sometimes less about moral awakening than about risk management. If an attraction generates complaints, lawsuits, or bad press, operators search for alternatives that preserve the revenue stream and the emotional payoff while reducing visible harm. A dunk tank can be presented as “all in good fun” precisely because it is wet rather than bloody. But the earlier lineage matters, especially when the target is still racialized.

The archival and museum record suggests that these transitions occurred unevenly. Some venues moved to wooden heads or caricatured targets, keeping the act of aiming at Blackness while removing the legal and physical complications of using an actual person. That shift is often described as progress, and in one narrow sense it is. But it also underscores how the core entertainment—the permission to attack a racial caricature—remained marketable.

Even when the “dodger” was no longer a living worker, the consumer lesson stayed intact: harm, or the simulation of harm, could be pleasurable when directed at the right kind of body.

The cultural technology of dehumanization

African Dodger belongs to a broader universe of late-19th- and early-20th-century racist play objects: board games, target games, toys, and novelty items that pictured Black people as buffoons, animals, threats, or perpetual children. The point of these objects was not simply to offend. It was to circulate a story about who counted as fully human.

The MDPI article on representational violence makes this explicit by connecting the physical aggression of carnival games to a larger pattern in which Black children and adults were repeatedly positioned as legitimate targets in play and media. The argument is not that every toy causes every act of violence, but that cultural products can normalize a worldview in which violence feels natural and justified.

This is where the game becomes more than a gruesome curiosity. It becomes a diagnostic. It shows how racism could be engineered into an experience: pay money, aim, throw, win, laugh, repeat. The body learns what the law and the sermon and the advertisement also teach: that someone else’s pain is not only acceptable but entertaining.

When scholars and museum professionals discuss such objects, they often emphasize how they functioned as propaganda for segregation. If Black people are depicted as stupid or invulnerable or deserving of harm, then excluding them from schools, juries, voting, and public accommodations can be framed as common sense rather than injustice. The caricature does political work.

And the violence does psychological work. It builds muscle memory—literal and social—around the idea that a Black person’s discomfort is not a problem that needs solving but a resource that can be mined for amusement.

Resistance, discomfort, and the limits of reform

It is tempting, in writing about African Dodger, to hunt for a clean narrative of condemnation: a decisive ban, a national revulsion, a turning point after which America came to its senses. The record is messier. The Gloucester closure in 1888 suggests local action could occur, but it does not prove a moral consensus. The later persistence of the game into the 20th century suggests the opposite: that many communities either embraced it or tolerated it.

Still, the fact that closures and criticisms existed at all matters. It indicates that even in eras saturated with racial hierarchy, there were fault lines—moments when public officials, Black patrons, reformers, or simply liability concerns forced a response. Those moments are often hard to reconstruct because the archive tends to preserve the voices of institutions more than the voices of the people harmed.

One way to ethically approach that silence is to treat it as evidence, not emptiness. The absence of the “dodger’s” name in a newspaper notice is not neutral; it reflects how Black labor and Black suffering were routinely anonymized. The lack of detailed reporting on injuries is not proof that injuries were rare; it may be proof that injuries were unremarkable to editors and audiences who had been trained to see Black pain as background noise.

A modern journalist’s job, then, is not to manufacture certainty where the archive is thin. It is to explain what the archive reveals about power: who gets recorded, who gets protected, who gets to be the narrator, and who is forced to be a prop.

How to report on racist artifacts without reproducing their harm

Writing about African Dodger requires a set of ethical choices that are not merely stylistic. Every retelling risks either sanitizing the cruelty or sensationalizing it. The safest path is neither denial nor spectacle, but disciplined clarity.

First, names matter. The historical names containing slurs tell you what kind of permission structure the game relied on. But repeating those slurs gratuitously risks re-injury and risks centering shock over analysis. The compromise—used by many museums and scholars—is to reference the slurs as part of the record while choosing language that keeps the focus on meaning rather than provocation.

Second, context matters. The game should not be treated as a bizarre outlier. It belongs to the same continuum as minstrel caricatures, segregated leisure spaces, and the broader culture of racial violence that marked the post-Reconstruction era. The Gloucester example, embedded in a discussion of Black leisure and exclusion, is instructive because it shows how racist amusements operated right alongside ordinary recreation, shaping where Black people could go and what they might encounter when they got there.

Third, the victims matter. Even when the archive withholds names, reporting can refuse to treat the “dodger” as a mere historical accessory. He was a worker and a person whose body bore the cost of someone else’s amusement. That is not an abstraction; it is the whole story.

Finally, the afterlife matters. The point of documenting African Dodger is not to indulge in horror, but to understand how a society trains itself. If a culture can normalize paying to throw at a Black man’s head, it can normalize other forms of dehumanization as well. The mechanisms change. The underlying lesson—who is safe, who is disposable—can persist.

The history that lingers in the present tense

African Dodger is a 19th-century story with a long tail. It is also a story about American memory: what the nation archives, what it forgets, and what it explains away as “a different time.” The game was not merely a reflection of racism; it was a practice that helped make racism durable by embedding it in pleasure.

Museums that collect racist memorabilia often describe their work as a confrontation with denial: forcing viewers to see how thoroughly white supremacy saturated daily life, including children’s play and public entertainment. PolitiFact’s documentation of the 1942 camp brochure underscores this point. The materials survive not because they are harmless, but because they are evidence—uncomfortable proof of what institutions once treated as normal.

There is a final, unsettling clarity that emerges from the historical record: African Dodger did not require secrecy. It required a crowd. It required advertising. It required the confidence that participants would not be shamed for joining in. The booth was public because the hierarchy it performed was public.

If you want to measure how far a society has traveled, you can look at what it now refuses to call entertainment. But you should also look at what it continues to package as “just a game,” “just a joke,” “just a tradition,” even as the target remains the same. The past is not only what happened. It is what got practiced.

And for a long stretch of American history, cruelty was practiced for pocket change, three throws at a time.