By KOLUMN Magazine

In May 1985, an American city decided—out loud and on the record—that a residential neighborhood could become a battlefield. The decision did not unfold in secret. It was televised, narrated in real time, and later rationalized in the language of procedure. By nightfall, a block of West Philadelphia was gone: 61 row houses destroyed by a fire that officials allowed to burn; 250 people left homeless; and 11 members of a Black liberation group called MOVE dead, including five children.

The bombing of MOVE’s home at 6221 Osage Avenue is sometimes framed as an aberration—an unimaginable error, a civic malfunction, a catastrophe produced by a unique set of personalities and misjudgments. But the longer view, and the documentary record, suggest something more disturbing: the MOVE bombing was not merely a “bad day,” but a culmination. It was the endpoint of years of escalating antagonism between the city and a highly visible Black organization; a product of the era’s turn toward militarized policing; and a case study in how news coverage can both illuminate state violence and, paradoxically, cushion its accountability.

What the nation saw on May 13—smoke stacking above neat roofs, flames running the length of a block, residents staring at what had been their homes—was not only the destruction of property and life. It was the revelation of a political imagination in which domestic dissent could be answered with a weapon of war. It was also, crucially, a media event: a tragedy filmed as it happened, then packaged into competing narratives about “extremists,” “neighbors,” “law and order,” and a Black mayor whose administration would become permanently entangled with the act.

MOVE before the fire: A movement, a family, a problem the city could not—or would not—solve

MOVE was founded in Philadelphia by Vincent Leaphart, who became known as John Africa. The group’s worldview braided Black liberation politics with a back-to-nature philosophy and intense commitments to animal rights and anti-technology ideas. Its members lived communally, adopted the surname “Africa,” and practiced a form of disciplined separatism that made them both difficult to categorize and easy to caricature.

By the early 1980s, MOVE relocated to Osage Avenue in a largely Black, middle-class section of West Philadelphia. The house at 6221 Osage—owned by a former MOVE member related to John Africa—became the site of persistent conflict with neighbors over noise, sanitation, and confrontational public messaging. Complaints accumulated. City officials and police, for their part, treated MOVE as a chronic emergency: a political irritant and a practical problem whose every attempted solution seemed to deepen the impasse.

Philadelphia had already been through a MOVE crisis. In 1978, after an earlier standoff at a different MOVE location, a police officer was killed. Several MOVE members—later known as the “MOVE 9”—received long prison sentences. That history hardened the city’s posture toward MOVE and steepened the stakes of every subsequent encounter.

In the years leading to 1985, the city’s approach oscillated between negotiation and enforcement, with neither side conceding legitimacy to the other. The result was an unstable equilibrium: neighbors wanted relief, MOVE wanted autonomy and recognition, and officials wanted a decisive end to a problem that had become nationally embarrassing. The MOVE Commission—appointed after the bombing—would later criticize the city’s preceding policy as incoherent and enabling, a pattern that set the stage for catastrophic escalation.

May 13, 1985: A siege becomes an airstrike

On the morning of May 13, Philadelphia police arrived in force to execute arrest warrants and clear the house. Utilities were cut. A loudspeaker announcement—part warning, part performance—framed the confrontation in civic terms: “This is America,” the police message began, insisting the group comply with law.

What followed was not a conventional arrest operation. It was a siege. Police deployed tear gas. Gunfire erupted. Authorities would later report the use of over 10,000 rounds during the confrontation.

Then came the decision that still startles even in summary: police dropped an explosive device from a helicopter onto the roof of the MOVE house. The bomb ignited a fire. Officials chose, in effect, not to extinguish it. The city’s own historical documentation and later reporting describe officials holding firefighters back, citing danger from potential gunfire—an operational choice that allowed flames to move from one row house to the next, consuming the block.

Two people survived from inside the MOVE home: an adult, Ramona Africa, and a child, Birdie Africa (also known as Michael Ward). Eleven others died—six adults and five children. The names of the dead remain an essential corrective to abstraction: John Africa among them; children including Tree and Delisha Africa.

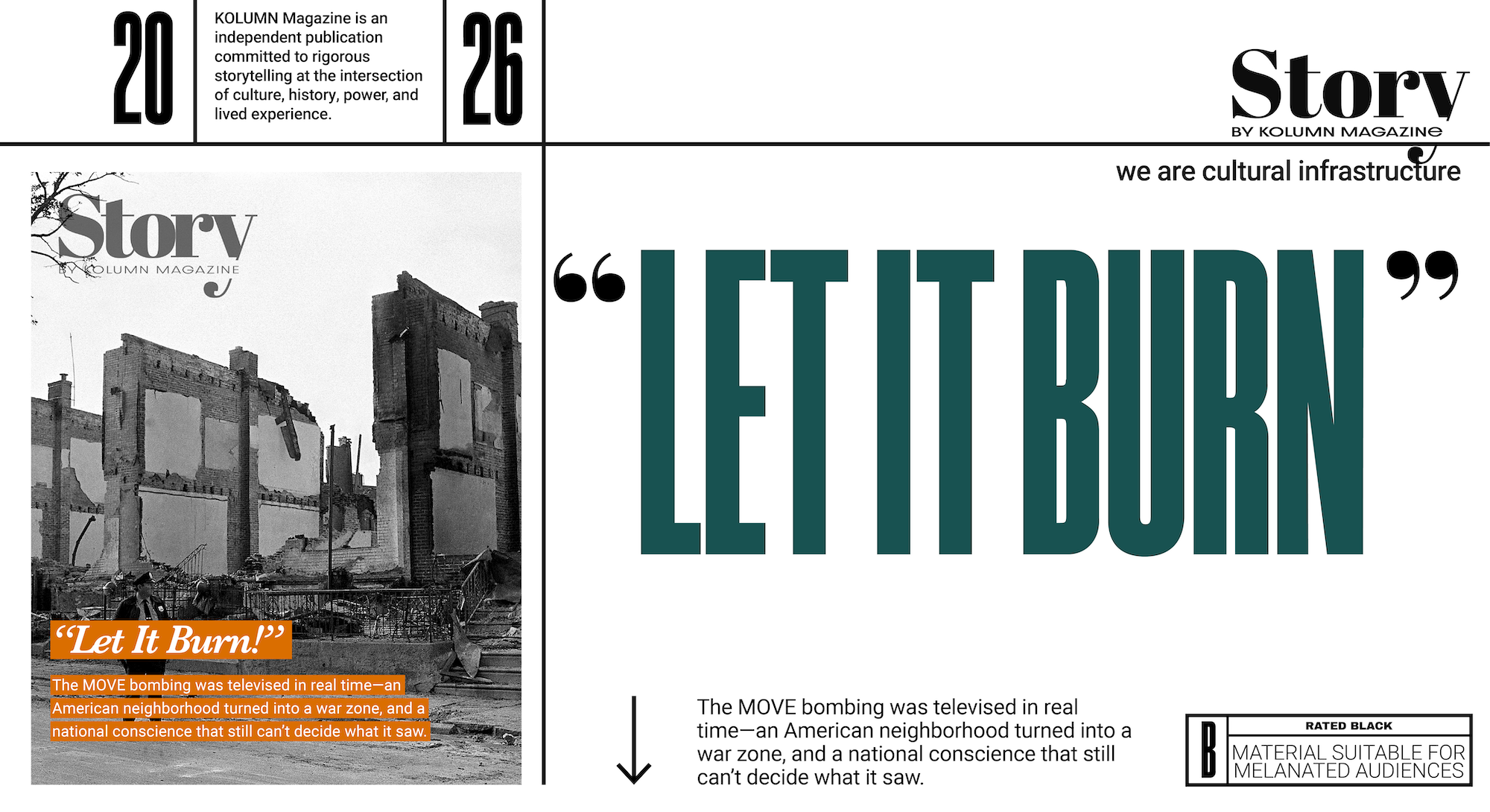

Sixty-one homes were destroyed, leaving roughly 250 residents homeless. In American civic life—where police power is typically imagined as bounded by streets, warrants, and courtroom rules—the image of a city effectively incinerating its own neighborhood became a kind of moral rupture.

What the cameras captured—and what they could not

Because the catastrophe unfolded in public view, the MOVE bombing produced a rare artifact: state violence that was not only documented after the fact but witnessed while it occurred. Local television coverage, later resurfaced and analyzed, shows the event’s most chilling feature: the apparent normalcy with which an extraordinary act—the burning of a neighborhood—was treated as an ongoing situation to be managed. (youtube.com)

That “managed” quality shaped the public’s initial understanding. The early framing in many mainstream outlets emphasized confrontation: MOVE as an armed, disruptive group; police as responders to a dangerous barricade; the fire as an unintended consequence rather than a foreseeable outcome of dropping an explosive on a row house. This is not to say the press collectively excused the city—shock and disbelief were widespread—but that the first narrative template was procedural and tactical, not moral and structural.

Yet there was another truth visible on the broadcast feed: the residents. The people who lived next door to MOVE—many of whom had wanted the conflict resolved—also became victims of the city’s chosen method. Their loss complicated the simplistic binary of “police vs. radicals” and forced a deeper question: whose safety, exactly, was being protected when officials made decisions that destroyed dozens of homes?

In the decades since, Black press, Black scholars, and community historians have argued that much of the early mainstream coverage failed to fully grapple with the racial and political context: a city with a long record of aggressive policing in Black neighborhoods; a Black mayor governing amid expectations that he would restore order without betraying a community’s demand for justice; and a national climate increasingly comfortable with the language of “war” applied to domestic problems.

The Black mayor and the politics of legitimacy

The MOVE bombing cannot be separated from the fact that Philadelphia’s mayor, W. Wilson Goode, was the city’s first Black mayor. That reality introduced a volatile layer of symbolism to an already explosive situation. For some, Goode’s administration represented a new era—proof that political inclusion could reshape public power. For others, the bombing became evidence of the opposite: that representation could coexist with, and even administer, the same coercive machinery long used against Black dissent.

Goode’s defenders have often emphasized that he inherited a combustible conflict and relied on advisors and police leadership in a rapidly evolving standoff. Critics—especially within Philadelphia’s Black political and activist communities—have argued that whatever the administrative dynamics, the outcome is the measure: a Black-led city government authorizing an act that many still describe as the most extreme instance of municipal violence against U.S. civilians in modern memory.

This tension would become part of the event’s national impact: the MOVE bombing complicated simplistic stories of racial progress. It forced observers to confront a harder proposition—that systems can be racialized even when led by people of color, and that the legitimacy of state power is not redeemed by the identity of its managers.

The MOVE Commission: “unconscionable,” and still not enough

In the aftermath, the city established a special investigative body commonly known as the MOVE Commission. Its findings would become one of the most quoted official judgments in the history of American policing: dropping a bomb on an occupied row house, the commission concluded, was “unconscionable.”

And yet, the commission’s moral clarity did not produce commensurate legal accountability. No city officials were criminally charged for the bombing itself, a fact that has remained central to the event’s long tail of grievance and unresolved civic trauma.

Civil litigation brought some measure of legal recognition: a federal jury later found the city liable for excessive force and constitutional violations in connection with the operation, resulting in financial judgments. But money—distributed years later—could not reconstruct the lost community, nor could it fully settle the question of how a decision so starkly condemned as “unconscionable” could still fail to generate criminal consequence.

The gap between official condemnation and practical accountability became, for many observers, the real lesson of MOVE: not only what the state can do, but what it can survive.

News coverage as national mirror: how MOVE became a template for “extremism”

Nationally, the MOVE bombing landed in a media ecosystem primed for certain storylines. The 1980s were a decade of “law and order” politics, expanding police tools, and a growing appetite for framing social conflict as a security problem. In that environment, MOVE was often described with a vocabulary that made escalation feel plausible: “militant,” “radical,” “barricaded,” “armed.”

Those descriptors were not invented out of thin air—there was gunfire, there were prior confrontations—but they mattered because they functioned as a narrative permission slip. When a group is defined primarily as a threat, the range of “reasonable” responses expands. When a neighborhood is defined as a staging area for an “operation,” it becomes easier to treat homes as collateral.

At the same time, local coverage—especially in Philadelphia—contained a more intimate, more complicated portrait: neighbors angry at MOVE and yet devastated by the city; reporters absorbing the shock of watching an American block burn; and a municipal government caught between admitting failure and defending itself. The result was a layered media record that scholars continue to mine for insight into how public consent is manufactured in moments of crisis.

What is striking, decades later, is how often MOVE is referenced as a precedent whenever state power confronts a “fortified” domestic group—whether in discussions of sieges, police militarization, or crisis negotiation. Even Washington Post retrospectives have used MOVE to underline the stakes of escalation: a reminder that policing can cross a threshold beyond which the outcome is no longer “restoring order,” but producing death.

The Black press, memory, and the argument over what MOVE “meant”

Black-oriented outlets and cultural commentators have long insisted that MOVE cannot be understood solely as a policing story. It is also a story about how Black radicalism is treated when it refuses assimilationist scripts—when it is noisy, inconvenient, morally absolutist, and unwilling to translate itself into mainstream respectability. Ebony, for instance, has repeatedly returned to MOVE through the lens of relevance and memory—asking why the bombing still resonates and how it fits into broader patterns of state violence against Black communities.

This is where the event’s national impact becomes less about Philadelphia and more about the American repertoire of forgetting. In many U.S. cities, police violence enters the archive as scandal, then fades into footnote. MOVE, despite its astonishing visuals and official condemnation, has often hovered at the edge of national consciousness—invoked occasionally, then displaced by newer tragedies. Public media in recent years has described it as “largely forgotten,” a phrasing that is itself an indictment: how does a city bombing its own residents become something the nation misremembers as obscure?

The fight over meaning has never ended. For some Philadelphians, MOVE remains synonymous with neighborhood disruption and fear. For others, MOVE is inseparable from the city’s willingness to impose collective punishment on a Black neighborhood. Both perspectives coexist in the historical record, and ethical reporting requires acknowledging that the victims of May 13 included not only MOVE members but also the surrounding families whose homes were sacrificed to a strategy.

A second scandal: The dead, the institutions, and the afterlife of disrespect

As if the bombing were not enough, the story acquired a later chapter that reanimated national outrage: the mishandling and retention of victims’ remains. Reporting and institutional investigations revealed that the bones of MOVE children—most prominently Tree and Delisha Africa—were retained and used in academic contexts without family consent, moving through institutions including the University of Pennsylvania and Princeton. The disclosures ignited condemnation from Black anthropologists and archaeologists and forced universities to confront ethical failures that compounded the original violence.

Princeton produced a formal report detailing its findings and recommendations. Philadelphia released an independent investigative report examining how the city handled the remains after 1985, including record-keeping failures and troubling procedural gaps; news coverage highlighted recommendations such as revisiting how deaths were classified and how families were notified.

Then, even more recently, the Penn Museum publicly stated that additional MOVE remains were uncovered during an inventory process—information communicated to families, with reunification “in process” pending their wishes. The recurrence of “newly discovered” remains decades after official assurances deepened the sense that MOVE’s victims were denied not only life and home, but also the basic dignity of proper care in death.

This afterlife scandal matters for understanding national impact because it illustrates something structural: the same systems that can justify extraordinary violence can also normalize extraordinary disrespect. The bombing was an act of power. The subsequent handling of remains was an act of institutional entitlement—a quieter violence that signaled, again, whose bodies are treated as subjects and whose as specimens.

Official apologies and the politics of timing

For years, the city’s gestures toward accountability felt partial and delayed—statements without transformation. In 2020, Philadelphia City Council passed a formal apology resolution acknowledging the “enduring harm” caused by the decisions leading to May 13, 1985, and establishing an annual day of reflection.

The timing mattered. The apology came amid a national reckoning over policing and racial violence, when institutions across the country were issuing overdue acknowledgments. In that context, MOVE resurfaced not just as a Philadelphia tragedy but as a national case study in how state violence can be retroactively reclassified—from “tactical decision” to “moral failure”—without necessarily altering the structures that made it possible.

By the mid-2020s, new commemorations and exhibits signaled a shift from reluctant remembrance to structured public memory. The city opened a permanent exhibit; local institutions hosted symposia; and community members renewed calls for memorialization at the site itself, including efforts by Mike Africa Jr. to preserve the house as a space of reckoning rather than a quiet return to normal.

The struggle over how to remember MOVE is, in many ways, the struggle over what kind of country the United States believes itself to be. A nation that can incorporate MOVE as history—fully, honestly—must also admit that “public safety” has sometimes been a language for public destruction.

The legacy in policing: What MOVE foreshadowed

It is tempting to treat the MOVE bombing as a singular horror: the only time a U.S. city dropped a bomb on its own residents. But its operational logic—overwhelming force, siege tactics, treating a domestic standoff as war—has become less exceptional in modern policing culture.

The last four decades have seen the spread of SWAT deployments, military-grade equipment transfers, and doctrinal approaches that conceptualize certain neighborhoods and populations as threats requiring extraordinary response. MOVE sits at the extreme end of that spectrum, but it belongs to the same family of assumptions: escalation is control; force is deterrence; collateral damage is acceptable if the target is stigmatized enough.

The Washington Post, reflecting on MOVE in the context of later standoffs, underscored precisely this point: the difference between a crisis that ends without fatalities and one that becomes a historic atrocity often lies in whether officials can resist escalation, whether they regard surrender as the goal—or annihilation.

MOVE also became a cautionary reference in cultural work: documentaries like Let the Fire Burn reintroduced the story to new audiences; artworks and public memorial debates surfaced questions about who gets commemorated and how civic shame is managed. These cultural responses matter because they represent another form of accountability: when institutions fail to punish wrongdoing, communities often turn to narrative and art to keep the record from closing.

The hardest question: Why it could happen, and why it still matters

A careful reading of the MOVE record—official findings, journalism, institutional reports—leads to an uncomfortable conclusion. The MOVE bombing was not only the product of misjudgment. It was also enabled by ideology: the belief that certain forms of Black dissent are inherently illegitimate; that disorder justifies exceptional violence; and that political costs can be managed if the targets are sufficiently marginalized or stigmatized.

It also forced a reckoning with the limits of American liberalism. The United States speaks the language of rights while repeatedly staging crises in which rights are treated as negotiable. MOVE demonstrated how quickly a city can slide from “enforcement” into something closer to collective punishment—how rapidly the police function can become a war function—and how difficult it is to impose consequences afterward, even when official commissions condemn the act in moral terms.

And then there is the quieter legacy: the neighbors who lost homes; the children whose names became symbols; the survivors who carried trauma into courtrooms and classrooms; the institutions that, decades later, still struggled to treat Black remains with dignity. MOVE is not merely a story of a bombing; it is a story of what follows when the state refuses to see certain people as fully protected by the promises it recites.

In 2025, public media again described the MOVE bombing as “largely forgotten,” even as Philadelphia marked a major anniversary. That phrase should not be accepted as neutral description. Forgetting, in a democracy, is a political act. The MOVE bombing remains relevant precisely because it shows what happens when a city’s fear becomes policy, when policy becomes spectacle, and when spectacle becomes history without consequence

If the nation is serious about preventing the next Osage Avenue—whatever form it takes—it must do more than commemorate. It must interrogate the logic that made a bomb seem like an answer, and the narrative habits that let that answer stand.