By KOLUMN Magazine

On a winter night in Minneapolis, the sound people remember is not the siren. It is the whistle.

Neighbors came outside—some with phones, some with noise-makers—because that is what you do when you believe the state has arrived to take someone. Federal agents were working the streets as part of a high-visibility immigration crackdown. Then Renée Good, a 37-year-old U.S. citizen, was shot and killed by an ICE officer during that enforcement operation, catalyzing protests, lawsuits, resignations inside the federal system, and a national argument about “over-policing” that—depending on where you sit—either feels unprecedented or painfully overdue.

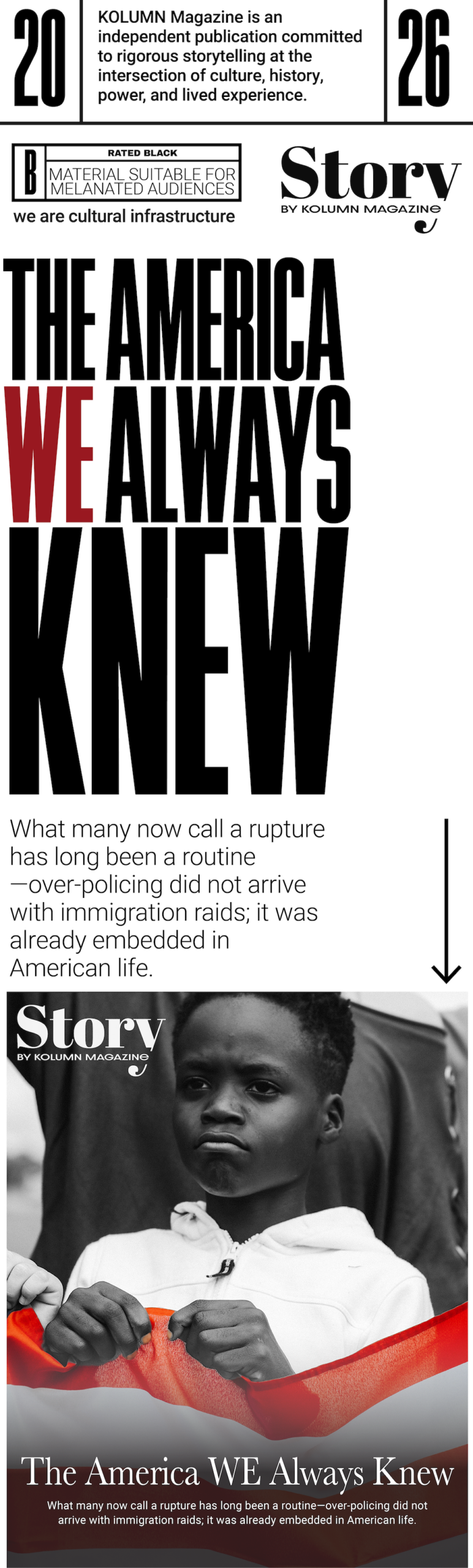

The phrase “over-policing” is doing a particular kind of work in the public conversation: it suggests something has recently become excessive, something has newly tipped from normal to intolerable. The current outcry—intensified by the Minneapolis shooting, by scenes of masked agents and crowd-control munitions, by alleged warrantless arrests and sweeping stops—has been widely framed as a new dynamic.

But for Black Americans, the central claim embedded in today’s outrage is also the central error: what many are encountering as novel has long been operational. Aggressive, preventive enforcement—stops untethered from clear evidence, searches justified after the fact, force defended as protocol, accountability delayed by process—has been a defining feature of modern American policing. What shifts from era to era is not the logic but the locus: the neighborhoods targeted, the legal authority invoked, the political language used to dignify the same practices.

If you want to see the intersection—not just the parallel—between today’s ICE over-policing and the pleas Black Americans have made for decades, you do not start with immigration. You start with the stop.

The stop as a governing idea

In American law, the stop is where theory meets a person’s body.

“Terry stops” originate in Terry v. Ohio (1968), when the Supreme Court held that police may briefly detain someone without probable cause if an officer has “reasonable suspicion” that crime is afoot—and may frisk for weapons if the officer reasonably believes the person is armed and dangerous.

“Terry” is often taught as a narrow compromise: a limited intrusion to prevent harm. In practice, it became a template for proactive policing—an expandable doctrine that grants street-level discretion enormous power, especially where institutional incentives reward volume. Once the stop is normalized, the country’s day-to-day experience of the Constitution becomes unevenly distributed: some people live in a world where the state must justify itself before acting; others live in a world where they must justify themselves after being acted upon.

Stop-and-frisk, in its most infamous modern form, took Terry’s “reasonable suspicion” and turned it into an institutional program. New York City’s stop-and-frisk regime, heavily concentrated in Black and Latino neighborhoods, led to hundreds of thousands of stops a year at its peak. In Floyd v. City of New York (2013), a federal judge found that the NYPD’s practices violated the Fourth Amendment and were carried out in a racially discriminatory manner under the Fourteenth Amendment.

The vocabulary matters. “Reasonable suspicion” is not probable cause. It is not proof. It is a standard built to move quickly, justified by risk, and implemented through discretion. That discretion is where disparities live.

National Academies research has noted how proactive policing decisions—who is stopped, questioned, or frisked—can generate racial disparities even when officers claim race is not a motive, because discretionary choices are shaped by deployment patterns, assumptions, and institutional culture.

The question today is what happens when that discretionary architecture migrates from municipal policing into federal immigration enforcement—especially during a political moment that explicitly celebrates spectacle and volume.

The immigration badge, the policing method

To many Americans, immigration enforcement still reads as administrative: paperwork, interviews, hearings. That picture is incomplete, and it is increasingly obsolete.

Policy analysts have described the second Trump administration’s enforcement approach as one that intensifies interior removals and ramps up detention capacity, accelerates fast-track removal authorities, increases coordination across federal agencies, and expands partnerships with state and local law enforcement.

Reuters has reported a shift toward “bold sweeps,” confrontations with both migrants and U.S. citizens, and rising concerns over hiring and shortened training as the administration pushes to expand enforcement capacity.

And in cities and neighborhoods, the lived experience can look less like civil administration and more like street policing: unannounced operations, agents in tactical gear, vehicles and blockades, crowd-control weapons, rapid arrests, and contested narratives about threats and compliance.

This is not merely parallel to policing. In important ways, it is policing—executed under immigration authority.

A Harvard Law Review analysis from the Obama era noted that immigration enforcement, in significant respects, had become “indistinguishable from policing,” while remedies for harms lagged behind the capacity to do damage.

The contemporary intersection is therefore not only cultural (“this resembles what Black communities have said for years”). It is structural: the same proactive-enforcement logic, now operating through overlapping systems—local police, DHS components, deputized partnerships, and data-sharing pipelines that entangle criminal and immigration consequences.

For Black immigrants, advocates have long argued, police and ICE can function as “two sides of the same coin,” with aggressive neighborhood policing creating additional pathways into immigration detention and removal.

This is the connective tissue: the stop, the database, the discretion, the downstream punishment.

Why the outrage is framed as “new”—and why that framing fails

It is not hard to see why today’s public reaction is being marketed as novelty. There are genuinely recent elements:

A visible expansion in the scale and publicity of ICE operations, including large deployments characterized by local officials as invasions of civic space.

A catalytic death in Minneapolis that has become a national symbol, paired with intense scrutiny of official narratives and calls for accountability.

A legal and political escalation: lawsuits by Minnesota and Twin Cities leaders; threats from the White House regarding sanctuary jurisdictions; congressional pressure tied to DHS funding; and even articles of impeachment against the sitting DHS secretary.

Policy experiments by states to create avenues for civil-rights redress against federal agents, such as New York’s proposal to allow state-court suits over ICE civil-rights violations.

These are real developments. Yet “new” is doing something else, too: it permits the country to treat what is happening as an exception rather than an extension.

Black America’s recurring plea has not only been “police violence is wrong.” It has been more precise: proactive enforcement turns everyday life into a site of investigation; discretion becomes a weapon; rights become conditional; and accountability mechanisms are too weak to deter repeat harm. In that telling, the Minneapolis moment is not a departure. It is the plot continuing, with a new cast and an expanded jurisdiction.

You can hear this continuity in how communities respond. The “noise alerts” described in recent reporting—whistles and neighborhood warnings when agents appear—echo the informal survival infrastructure long present in overpoliced Black neighborhoods: the text thread that marks where patrol cars are parked; the community elder who tells teenagers what streets to avoid; the whispered advice that compliance is not protection, but resistance may be lethal.

What changes is who the broader public imagines as the default victim.

Those erased in the “new” debate: The names that built the argument

The contemporary framing of over-policing as a newly emergent crisis often proceeds without acknowledging the people whose deaths forced the nation to recognize the problem in the first place. This omission is not simply rhetorical; it alters the moral and analytical foundation of the debate. By severing present outrage from its origins, the country risks misunderstanding what is unfolding now and why it feels so familiar to Black Americans. The deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Philando Castile, Freddie Gray, and Eric Garner are not historical background noise. They are the connective tissue between past warnings and present realities.

George Floyd was murdered on May 25, 2020, in Minneapolis when a police officer knelt on his neck for more than nine minutes during an arrest over an alleged counterfeit bill. Floyd’s repeated pleas—“I can’t breathe”—were ignored as bystanders begged officers to intervene. His death was not the result of a high-risk chase or violent confrontation, but of routine enforcement escalated through indifference and excessive force. The global protests that followed transformed Floyd into a symbol not only of police brutality, but of how ordinary encounters can become fatal when discretion is unchecked and accountability is delayed. His killing crystallized the argument that over-policing is not about isolated misconduct, but about systems that normalize escalation.

Breonna Taylor was killed in her Louisville apartment when police executed a late-night no-knock warrant tied to a narcotics investigation that ultimately produced no drugs. Taylor, an emergency medical technician, was asleep when officers forced entry. Her death exposed the dangers of militarized policing tactics that collapse the boundary between public enforcement and private life. The no-knock raid became emblematic of how aggressive policing doctrines, justified as preventive or officer-protective, can produce lethal outcomes for people who are not suspected of crimes. Taylor’s case expanded the over-policing argument beyond streets and traffic stops, demonstrating that the home itself can become a site of state violence.

Philando Castile was shot and killed during a traffic stop in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, after calmly informing an officer that he was legally carrying a firearm. Castile complied with instructions, spoke clearly, and posed no discernible threat. His death underscored the instability and danger inherent in routine stops, particularly for Black drivers, where compliance does not ensure safety and legality offers no shield against fear-driven responses. Castile’s killing illustrated how pretextual enforcement—initiated for a minor traffic issue—can escalate rapidly into deadly force, a dynamic that now echoes in immigration stops framed as administrative encounters.

Freddie Gray died from catastrophic spinal injuries sustained while being transported in a Baltimore police van after an arrest for allegedly possessing a knife. Gray’s death drew attention to a less visible dimension of over-policing: what happens after arrest, once a person is removed from public view. His fatal injuries highlighted how harm can occur not only at the moment of contact, but during detention and transport, where oversight is minimal and responsibility is diffuse. Gray’s case revealed how systems can obscure accountability by fragmenting decision-making across multiple actors, a pattern mirrored in immigration detention, where abuse and neglect often occur far from public scrutiny.

Eric Garner was killed on a Staten Island sidewalk during an arrest for allegedly selling loose cigarettes. An officer placed Garner in a prohibited chokehold as he repeatedly said he could not breathe. The encounter was captured on video, yet accountability remained elusive for years. Garner’s death exposed the peril of enforcing minor offenses with overwhelming force and demonstrated the chasm between official policy and street-level practice. His final words became a refrain that linked disparate cases into a single indictment of over-policing: that trivial or civil violations should never justify lethal outcomes.

Together, these deaths formed the backbone of the modern critique of American policing. They established that over-policing is not defined solely by the worst outcomes, but by the conditions that make those outcomes possible: discretionary stops, aggressive tactics, racialized suspicion, and weak mechanisms for accountability. When today’s debates about ICE over-policing fail to name these individuals, they risk presenting the crisis as a sudden deviation rather than a continuation. Remembering these cases is not an exercise in memorialization alone; it is essential to understanding the present. What many now experience as shocking or unprecedented has already been lived, documented, and mourned. The difference is not the system. It is who is newly encountering it.

The policy comparisons that matter

To draw honest comparisons between ICE over-policing and the aggressive policing raised by Black Americans, you have to get specific—about legal standards, operational incentives, and accountability barriers.

1) Pretext and permission: From traffic stops to immigration stops

In criminal policing, the modern stop is often a pretext: a minor infraction used to justify investigation for something else. In immigration enforcement, the alleged “civil” purpose can function similarly: the encounter is framed as status verification, but it can become a gateway to detention, interrogation, and removal.

Recent commentary in The Atlantic has argued that legal and doctrinal developments can enable ICE officers to convert ordinary occurrences into pretexts for intervention, warning that “everyday” behavior can become a basis for escalating enforcement action with life-altering consequences.

In September 2025, the Supreme Court stayed limits on certain immigration enforcement tactics in Los Angeles, a decision widely read as lowering constraints on broad stopping practices and raising fears of increased racial profiling in sweeps.

If this sounds familiar, it is because Black drivers, pedestrians, and bystanders have long lived under a regime where the state’s first move is contact, not justification. The harm is not only the worst-case outcome—injury, death, or arrest—but the normalization of being searchable, stoppable, and detainable.

2) “Reasonable suspicion” as a lifestyle: Terry stops and their afterlife

Terry stops were sold as narrow and cautious. Their afterlife has been expansive.

The National Constitution Center and other legal summaries emphasize the rule: reasonable suspicion allows a stop; a reasonable belief someone is armed and dangerous allows a frisk.

But what begins as doctrine becomes culture. In communities where police saturation is high, suspicion becomes ambient: who you are, where you are, what you wear, who you walk with, how you speak—these become proxies for danger.

Immigration sweeps can replicate that atmosphere. Reuters reporting has described allegations of racial profiling and arrests without warrants during the Minneapolis-area surge, claims that DHS disputes, in a context where enforcement is justified through fraud allegations tied to a specific community.

The parallel is not that ICE is legally identical to municipal police. It is that the governing method—the discretionary stop as the engine of enforcement—produces the same predictable outcomes: disparate targeting, fear-driven compliance, and post-hoc rationalizations.

3) Programmatic volume: stop-and-frisk and “surge” enforcement

Stop-and-frisk was not a handful of bad stops; it was a system that produced stops.

That is why the Floyd ruling matters as more than history: it is a case study in how proactive policing becomes unconstitutional at scale—how the metrics of enforcement can overwhelm the constitutional requirement that each intrusion be justified.

Now look at “surge” immigration enforcement. In Minneapolis, DHS has described thousands of arrests under “Operation Metro Surge,” while lawsuits by the state and cities argue that the operation violates constitutional rights and invades civic authority.

Volume is not merely a number; it is an incentive. Systems that reward stops and arrests tend to generate stops and arrests—often by widening the definition of suspicion, and narrowing the meaning of innocence.

4) Masks, anonymity, and the accountability gap

One of the details repeatedly surfacing in contemporary reporting is agents obscuring their identities. Community outrage is not aesthetic; it is procedural. If you cannot identify an officer, you cannot effectively seek redress.

In Congress, proposals responding to the Minneapolis crisis have included requiring warrants, restricting masks, and altering detention practices—an attempt to rebuild basic accountability guardrails.

New York’s governor has endorsed a proposal to allow residents to sue ICE agents in state court for civil-rights violations—an explicit acknowledgment that existing federal pathways may be insufficient, especially given doctrines that shield officers.

Black Americans will recognize the pattern: remedies trail harms. Oversight trails innovation. And the burden of proof shifts to the harmed.

5) Use of force: when “compliance” becomes a fatal argument

George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Philando Castile, Freddie Gray, Eric Garner—are now a civic shorthand for the same claim: in the United States, contact with law enforcement can escalate to catastrophic force, and official narratives often begin by litigating the victim’s worthiness rather than the state’s restraint.

The Minneapolis case is echoing that structure. Video accounts, contested threat narratives, family demands for transparency, and the decision by DOJ leadership not to open a civil-rights investigation (as reported) have triggered resignations and intensified distrust—an institutional version of what Black communities have described for years: that accountability is discretionary too.

Time’s reporting suggests even some ICE personnel have expressed internal dissent and concern about training and deployment decisions, underscoring how enforcement expansion can outpace professional standards.

None of this is to claim equivalence between every police killing and every ICE encounter. It is to insist that the mechanism of harm—the escalation ladder, the presumption of threat, the rhetorical weaponization of “noncompliance”—is recognizable across agencies.

The intersection: Blackness, immigration status, and compounded vulnerability

Parallels become intersections when people occupy both worlds at once.

Black immigrants—Haitian, Jamaican, Nigerian, Somali, Afro-Latinx, and others—can be subject to both racialized criminal suspicion and immigration suspicion. Advocates have argued that aggressive policing in Black neighborhoods creates an “additional layer” of punishment for Black immigrants, for whom a stop can trigger not only local criminal consequences but detention and removal.

This intersection has also been documented in detention conditions and immigration incarceration. Organizations focused on detention have reported systemic abuses that fall heavily on Black migrants, framing immigration detention as an incarceration system shaped by anti-Black racism.

So when national media and political leaders talk about ICE over-policing as if it were a novel crisis, one response from Black communities is: welcome to the architecture. Another is: we have been trying to explain that the architecture was never limited to one agency.

Why “extension” is the more accurate diagnosis

If you want the more accurate conclusion—that the current state of over-policing is an extension of an older problem—you look for continuity in three places: doctrine, deployment, and narrative.

Doctrine: discretionary standards that travel well

Terry’s reasonable suspicion travels: it can be repackaged as “status checks,” “fraud investigations,” “public safety,” “suspicious behavior,” “officer safety.” The label changes; the discretion remains.

Deployment: saturation as a political choice

Whether it is stop-and-frisk concentrated in specific neighborhoods or a federal “surge” concentrated in specific communities, saturation is policy. It creates more encounters, which create more enforcement outcomes, which are then cited as proof the saturation was justified.

Narrative: fear as a permission structure

Over-policing relies on a story about danger: criminals, gangs, terrorists, “invaders,” fraud rings. In recent reporting, federal officials have justified Minneapolis deployments in connection with fraud allegations and broader enforcement goals, even as local officials and civil-rights advocates contest the methods and outcomes.

Fear is not incidental. It is the moral alibi.

The political moment: Why the country is listening now

A hard truth in American history is that grievances often become “national” only when they expand beyond those who have always carried them.

Black Americans have pleaded—often with documentation, litigation, and public protest—for the country to take over-policing seriously. They have described proactive stops as humiliating, dangerous, and constitutionally corrosive. They have pointed to deaths that turned ordinary contact into fatality. They have watched as reforms arrived slowly, unevenly, or symbolically.

Now, as immigrant communities and a broader swath of the public confront the same enforcement logic—pretext, saturation, escalation, limited recourse—the country is calling it a new crisis.

It is not new. It is newly visible.

And visibility, in America, is often the first step toward change—not because the harm has changed, but because the audience has.

What accountability could look like (and why it keeps failing)

Accountability is not one thing. It is a chain.

Front-end limits: warrants, clear standards for stops, restrictions on masking, transparent identification, strict limits on “sensitive locations,” and robust training requirements.

Real-time oversight: independent monitors, public reporting, body cameras where appropriate, and meaningful discipline for violations—lessons drawn from stop-and-frisk reform efforts after Floyd.

Back-end remedies: accessible civil litigation pathways, including state-level experiments aimed at overcoming the practical barriers victims face when federal officers violate rights.

Political accountability: budget leverage, hearings, resignations, and—at the outer boundary—impeachment efforts aimed at executive leadership.

But the recurring failure is that the enforcement state is often treated as an emergency instrument—expanded quickly in the name of crisis, and constrained slowly, if at all, when crisis passes.

That is why the “new dynamic” framing is so dangerous. If the country believes the problem began recently, it will search for recent fixes—without confronting the deeper engine that keeps producing the same result: discretionary, proactive enforcement regimes that treat certain communities as inherently stoppable.

The bottom line

The Minneapolis shooting did not create the question of over-policing. It clarified it.

It forced a broader public to confront what Black Americans have reported for generations: that a state confident in its own discretion will keep extending that discretion—into new neighborhoods, new policy domains, new bureaucratic categories—until the country decides that constitutional protections must be experienced as something more than words.

If there is an opening in this moment, it is not only to restrain ICE. It is to recognize the shared anatomy of over-policing across systems—and to stop acting surprised when the logic that governed one community is redeployed against another.

At minimum, the country can tell the truth about what it is seeing: not a rupture, but a continuation.