By KOLUMN Magazine

On an ordinary school day in Montgomery, Alabama, Claudette Colvin did something that—by the strict logic of Jim Crow—was not supposed to be imaginable. She refused. She refused the bus driver’s order, refused the mythology of white entitlement, refused the quiet coercion that told Black teenagers to survive by shrinking. She was 15 years old, carrying textbooks and adolescent certainty, and she decided she would not move. It was March 2, 1955—nine months before Rosa Parks would be arrested for the same defiance and ignite a mass boycott that reshaped the country’s political imagination.

Colvin’s name is now familiar enough to be invoked as a corrective—before Parks, there was Colvin—yet still too often treated as a historical footnote rather than what she was: an early catalyst, a legal witness, and a young working-class Black girl who absorbed the lessons of American hypocrisy and acted on them in real time. In the legal record, Colvin’s defiance becomes even more concrete: she was one of the plaintiffs in Browder v. Gayle, the federal lawsuit that ultimately dismantled bus segregation in Montgomery and across Alabama, affirmed by the Supreme Court in 1956.

What makes Colvin enduring—what makes her urgently modern—is not only the bravery of a single day, but the longer shape of what followed: the costs that came with refusing, the way respectability politics and gendered judgment narrowed her public usefulness to movement leaders, the decades in which she worked outside the spotlight as a nurse’s aide, and the late-life work of reclaiming her own record—literally—when she sought to have her juvenile arrest expunged.

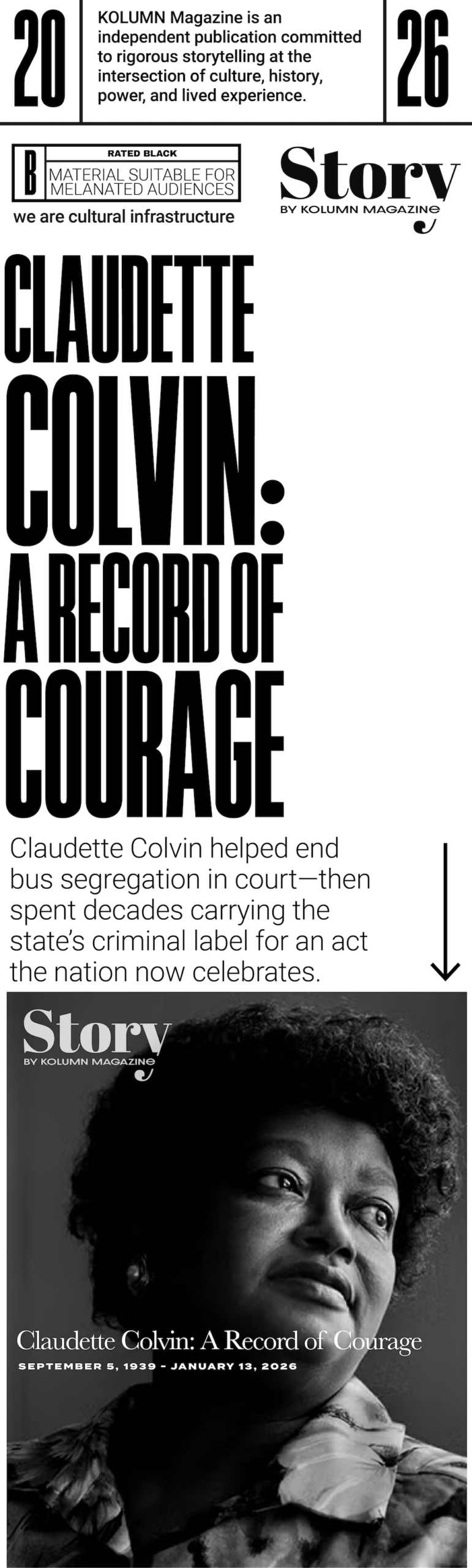

On January 13, 2026, news organizations reported Colvin’s death at 86, prompting renewed attention and public mourning—and, for many, a fresh confrontation with how American history chooses its icons.

This is a story about a teenager’s refusal, yes. But it is also a story about narrative power: who gets centered, why, and at what human cost. And it is a story about perseverance that did not look like speeches or podiums, but like long shifts, family obligations, and the quiet determination to keep living after becoming “the girl who caused trouble.”

Montgomery’s Buses, Montgomery’s Rules

To understand what Colvin did, it helps to recall how Montgomery’s bus system functioned as a rolling classroom in racial hierarchy. Black passengers made up a significant share of riders, but the city’s rules (and the drivers’ discretion) turned everyday transportation into a ritual of humiliation. Seats at the front were reserved for white passengers. Black riders were expected to sit behind the white section, and if the white section filled, Black riders could be ordered to surrender their seats—even if those seats were in the “Black” area—so that white passengers would not have to stand.

Drivers were not neutral functionaries; they were enforcers of a social order. They carried the authority of municipal ordinance, and they often carried the temper of men who believed, with the casual certainty of custom, that Black teenagers should not test them.

Colvin was a student at Booker T. Washington High School, growing up in a poor Black neighborhood in Montgomery. Her childhood, like the childhoods of many Southern Black girls, was shaped by constraint and improvisation—by limited resources, crowded living arrangements, and the constant navigation of what could be said and where.

But Colvin also belonged to an ecosystem of Black civic education that is sometimes missed in popular retellings. She participated in youth activism—part of the NAACP Youth Council structure that trained young people to understand constitutional claims as moral claims, and to see segregation not as fate but as policy.

That civic education mattered on March 2, 1955, because it gave her a vocabulary for what she was feeling. She wasn’t just angry; she had been taught that she had rights. She had been taught to identify the lie at the core of “separate but equal.” She had been taught that the country’s founding documents contained promises that white Montgomery refused to honor.

“History Had Me Glued to the Seat”

Colvin later described her refusal with language that has echoed for decades: she felt pinned down by history—Harriet Tubman on one shoulder, Sojourner Truth on the other—an internal chorus insisting she should not cooperate with her own erasure.

That day, Colvin boarded a bus after school and sat in a row that sat behind the white-only section. As the ride progressed, the bus filled. A white woman boarded and was left standing in the front. The driver demanded that several Black passengers give up their seats. Some did. Colvin did not.

Her refusal was not polite in the way American memory often prefers its heroes. It was teenage defiance, sharpened by humiliation and principle. Accounts describe a scene in which police were called, Colvin argued that she had paid her fare and had a right to sit, and officers forcibly removed her from the bus.

The violence of the removal—and the fear that came with it—matters. Colvin later described being terrified during the arrest, including fear of sexual violence, a fear that was not irrational in the context of the South’s long record of racialized assault and impunity.

She was charged with offenses that reflected the state’s reflex to criminalize resistance: violating segregation rules and additional allegations related to the arrest. The point was not merely to remove her from the bus; it was to mark her, in the official record, as the kind of person whose protest could be dismissed as misconduct.

In that way, Colvin’s story belongs not only to civil-rights history but also to the history of how the state manufactures “criminality” for those who challenge it—especially Black children.

Why Colvin Was Not “The Face”

It is one thing to be brave. It is another to be chosen as a symbol.

Within Montgomery’s Black leadership circles, there was outrage at Colvin’s arrest. But outrage did not automatically translate into mobilization around her case as the movement’s public test. Many accounts emphasize a set of concerns—her age, her economic status, her temperament—that made established leaders wary of using her as the central plaintiff for a mass campaign.

These concerns are often summarized with a blunt phrase: respectability politics. The idea was that the person selected to represent the movement should be difficult to smear—a working adult, steady, “proper,” and able to endure intense public scrutiny. In practice, this often meant that the movement’s public face would be shaped by middle-class norms and patriarchal expectations about women’s behavior and sexual history.

Colvin, a teenager, was deemed “too volatile” by some retellings; she had argued with officers; she had not performed the quiet, saintly patience that white audiences expected from Black suffering.

And then there was the factor that became decisive in the cruel calculus of public strategy: Colvin became pregnant. Some movement leaders feared—reasonably, given the moralistic climate—that segregationists would weaponize her pregnancy to discredit the cause or distract from the constitutional issue at hand.

This is where Colvin’s story becomes especially instructive for the present. Movements are made by imperfect people, but the historical record often “cleans” them to fit a parable. Colvin did not fit the preferred parable. She was a Black girl, poor, outspoken, and vulnerable to the sexual scrutiny that has long policed Black women’s lives. She carried, in her person, too many of the biases that America uses to dismiss Black girls: she was “mouthy,” she was “fast,” she was “trouble.”

Her refusal was no less courageous for any of this. But her public usefulness was constrained by it.

The Legal Throughline: Browder v. Gayle

If the popular story of the Montgomery bus boycott is told as an uprising sparked by one woman’s arrest, the legal story is more complex—and, in some ways, more radical.

On February 1, 1956, attorney Fred Gray filed Browder v. Gayle in federal court, a class action suit that challenged the constitutionality of bus segregation in Montgomery. The plaintiffs were Black women whose daily lives had been shaped by the indignities of the bus system: Aurelia Browder, Susie McDonald, Mary Louise Smith, Jeanatta Reese, and Claudette Colvin. Reese later withdrew after intimidation and threats—an important reminder that segregation was enforced not only through law but through terror.

The lawsuit’s strategic brilliance was that it bypassed the slow grind of state courts and aimed directly at the constitutional heart of segregation under the Fourteenth Amendment. The Library of Congress’s account of the boycott-era legal strategy notes that Rosa Parks was omitted from the federal case in part because her state case was still moving through the courts, and lawyers sought to avoid the perception that they were evading that process.

Colvin’s role in Browder was not symbolic; it was evidentiary. She testified. Her lived experience—what the bus rules meant, how they were enforced, what it felt like to be ordered to move—became part of the machinery that forced the federal judiciary to reckon with segregation’s everyday cruelty.

In June 1956, a three-judge federal panel ruled that Alabama’s bus segregation laws were unconstitutional. The decision was affirmed by the Supreme Court later that year, and the ruling effectively ended bus segregation in Montgomery and across the state.

This legal timeline matters because it clarifies a recurring American misunderstanding: the boycott was a mass action, and Rosa Parks was a catalytic figure, but the dismantling of bus segregation rested on a structure of legal and civic work that included lesser-known plaintiffs and witnesses—often women—whose names were rarely celebrated with the same fervor. Colvin’s story is a prime example of how a movement can rely on someone profoundly, while still leaving her behind in the public narrative.

The Aftermath: “Troublemaker” as a Life Sentence

What happened to Colvin after her arrest is one of the most revealing parts of her story: she paid for her defiance not just in court, but in social standing, employment prospects, and personal safety.

Reporting and retrospective accounts describe how she struggled in Montgomery afterward—ostracized, treated as a liability, and branded as a troublemaker in a city where that label could follow you into every job interview, every church pew, every landlord’s decision.

The legal case that helped break segregation did not automatically protect her from the retaliation and stigma that came with being visible. That is another throughline that remains painfully contemporary: the costs of protest are rarely distributed evenly. Teenagers, working-class people, and women—particularly Black women—often carry consequences that the history books omit.

Eventually, Colvin left Montgomery and moved to New York. There, she worked for decades as a nurse’s aide—labor that is essential, intimate, and chronically undervalued. The Guardian notes that she became a nursing assistant after moving north, a life path that stood in contrast to her earlier dreams of becoming a civil-rights attorney.

There is something deeply American in that trajectory: a young person touches the edge of world-changing history, then disappears into the workforce that keeps society functioning. Nursing homes, hospitals, caregiving work—these places are full of people whose names will never appear in public commemorations, even when those people once altered the country’s direction.

Colvin’s endurance was not a single dramatic act; it was the persistence of living with what that act cost, and still continuing.

Memory, Myth, and the Nation’s Taste for a Clean Story

America likes civil-rights history when it can be arranged as a morality play: one tired seamstress, one courageous sit-in, one triumphant Supreme Court decision. Real life is messier. Movements are coalitions, arguments, compromises, and strategic decisions made under threat.

Colvin’s story forces a reconsideration of how those decisions were made—and who they excluded. The discomfort around her age, her class, her temperament, and her pregnancy wasn’t simply personal prejudice; it reflected an environment in which white power structures used any available “flaw” to delegitimize Black resistance. Movement leaders responded to that threat by selecting figures least vulnerable to smear. In doing so, they sometimes reproduced hierarchies inside the movement itself.

This is not an argument against Rosa Parks’ centrality. Parks was not a random tired woman; she was an experienced activist. She was a deliberate choice, and the boycott required precisely the kind of steadfast public figure she became. But Colvin’s story complicates what the public often assumes: that movements simply “happen” around the first brave person. In fact, movements are built—carefully—by people making strategic, and sometimes painful, decisions.

The problem arises when strategy becomes memory, and memory becomes myth. When that happens, the nation forgets that it was often Black girls—unprotected, uncelebrated—who forced the first cracks in Jim Crow’s wall.

Clearing the Record: The Fight for an Unfinished Justice

In 2021, Colvin sought to have her juvenile record expunged—an act that was both personal and political. It is difficult to overstate what it means for a civil-rights pioneer to carry a criminal record for decades for what history later recognizes as moral courage.

Multiple outlets reported on this effort, noting that the record and the probation status attached to it remained a point of concern. The legal filings themselves, including a motion and supporting affidavit, framed expungement as a corrective—an attempt to align the official record with the moral reality of what happened.

Ebony’s coverage emphasized the symbolic dimension: clearing the record was not only about Colvin’s name, but about what it would mean for Black children to see that the system’s punishments are not the final word—that the state can be made to admit it was wrong.

That expungement effort is a direct bridge to contemporary debates about youth criminalization, juvenile records, policing, and the long tail of “minor” charges that follow people into adulthood. Colvin’s case is a reminder that the line between “criminality” and “courage” is often drawn by power, not principle.

A Black Girl Pushout Story, Before We Had the Phrase

In 2016, The Atlantic used Colvin as a historical anchor in an essay about the criminalization of Black girls in schools and society—what scholars and advocates have described as patterns of discipline, surveillance, and punishment that funnel Black girls toward the juvenile and criminal legal systems.

Colvin’s story is not identical to modern school policing or digital-age surveillance, but the structural rhyme is unmistakable: a Black girl asserts her rights; authority responds with force; the system constructs her resistance as a behavioral problem; community institutions debate whether she is “respectable” enough to defend publicly; and the long-term consequences land on her body and her future.

When Colvin said she felt “history” holding her down, she was also describing something else: a moral intelligence that arrives early for children who live under unjust rules. That intelligence is often treated as insolence by adults invested in keeping peace with the status quo.

Today, many of the most visible justice movements are youth-driven—students organizing walkouts, teenagers documenting police encounters on phones, young activists articulating demands around race, gender, climate, and democracy. Colvin’s story offers both inspiration and warning: courage is powerful, but systems retaliate, and movements must build structures of care that do not abandon the young people who ignite them.

Recognition Arrived Late—But It Arrived

For years, Colvin’s story circulated mostly in specialized civil-rights histories, activist spaces, and among those who study the movement’s gender dynamics. Broader public recognition accelerated with books and cultural attention, including Phillip Hoose’s award-winning young adult biography, Claudette Colvin: Twice Toward Justice, which won the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature

This kind of recognition matters because it changes who is available as a model. When young readers encounter Colvin, they encounter a civil-rights hero who is not packaged as a perfect adult saint. They encounter someone closer to themselves: a teenager, overwhelmed and determined, acting from conviction and emotion at once.

KOLUMN Magazine’s own reporting has also contributed to this widening lens, noting how Montgomery institutions have recognized Colvin through art and exhibition—evidence that public memory can be expanded not only through textbooks but through cultural stewardship.

And when Colvin died on January 13, major outlets treated her as what she always was: a central figure of the early movement, a plaintiff in a landmark case, and a person whose life extended far beyond one bus ride.

What Claudette Colvin Means Now

If the civil-rights movement is often taught as a story of triumphant progress, Colvin’s life reintroduces the movement’s human cost—and the incompleteness of its victories.

1) She expands the definition of leadership

Colvin was not a minister, not a national spokesperson, not a polished adult with institutional backing. She was a Black schoolgirl with a clear sense of right and wrong. Her leadership was situational, moral, and immediate. In an era when many institutions still discount youth voices—especially Black girls—her story argues for taking young people seriously as political actors.

2) She exposes the costs of “winning”

Browder v. Gayle helped end bus segregation, but Colvin’s life shows that even legal victories can leave individuals carrying wounds and stigma. The movement advanced; she struggled. This is not a failure of her character; it is a reality of how societies extract sacrifice from ordinary people.

3) She complicates respectability politics in the present

Movements today still face pressures to choose “perfect victims” and “ideal messengers.” Colvin’s sidelining—due to age, class, and pregnancy—reveals how harmful that pressure can be, and how it can replicate social hierarchies inside liberation struggles. Her story invites modern organizers and institutions to build strategies that do not discard those who are easiest to demonize.

4) She bridges civil rights and contemporary justice fights

Colvin’s expungement campaign connects 1955 to the present-day reality of juvenile records, probation systems, and the bureaucratic afterlife of arrests. The civil-rights struggle did not end; it evolved into fights over policing, courts, schools, and the administrative machinery that shapes opportunity.

5) She reminds us that history is edited—and can be re-edited

The most important legacy Colvin leaves may be this: it is possible to correct the story. Not perfectly, not fully, but meaningfully. When her record was cleared, when institutions displayed her story, when journalists retold her life at her death, the country demonstrated that the archive is not fixed. Memory can be expanded. Omissions can be acknowledged.

The Enduring Image: A Girl, a Seat, a Constitution

On that bus in 1955, Claudette Colvin did not know how far her defiance would travel. She could not know that a federal lawsuit would later carry her name into constitutional history, or that her story would be used to interrogate the criminalization of Black girls decades later, or that she would spend much of her life as a nurse’s aide far from the city that first tried to punish her into silence.

What she did know—what she insisted on, with a teenager’s clarity—was that the world she lived in was wrong, and that compliance would make her complicit in that wrongness.

The throughline from then to now is not simply “progress.” It is perseverance: the perseverance to refuse indignity, the perseverance to live after the refusal, the perseverance to reclaim the record, and the perseverance to demand that the nation tell the story accurately.

Claudette Colvin’s commitment to equality did not end when the bus doors closed. It continued in the less visible places where many heroes live: in work, in family, in survival, and in the insistence—decades later—that justice should include the paper trail, too.