KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

The house that dared to call itself Hitsville

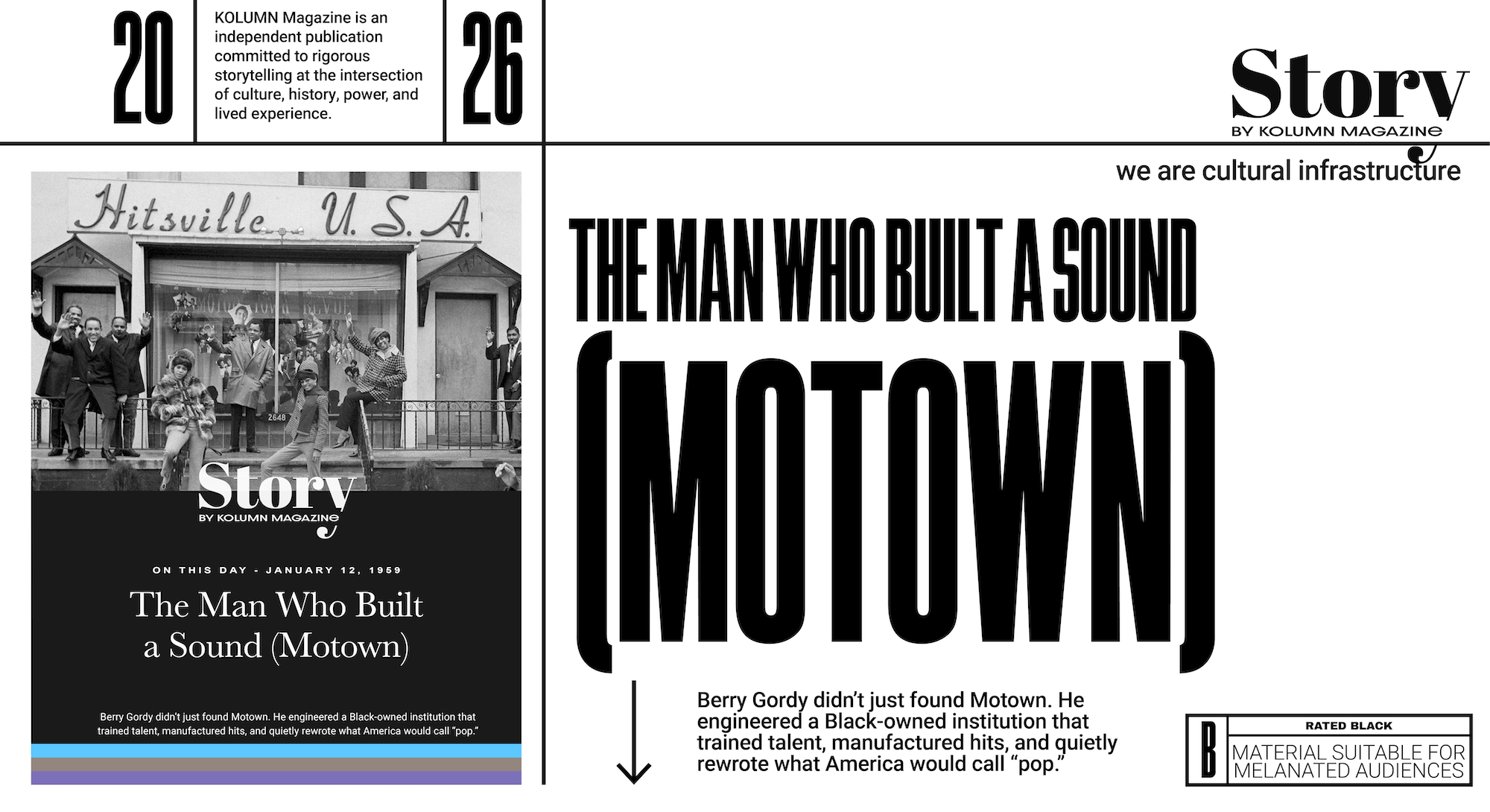

Before it was a museum, before it was a logo, before it became shorthand for an era, Motown was a building with a sign that read like an argument. Over the front of a modest two-family flat on West Grand Boulevard in Detroit, Berry Gordy Jr. hung a promise—“Hitsville U.S.A.”—as if optimism could be nailed to wood and made to hold. He moved his wife and young son upstairs and built a record company below, converting a photography studio at the back into Studio A.

That sign was premature, and it was prophetic. Gordy was not simply making records; he was building an institution designed to outlast a hit. In 1959, he founded Tamla Records with an $800 loan from his family’s cooperative savings—money that functioned like seed capital and, just as importantly, like accountability. Motown—added later that year—would become the flagship name, rooted in Detroit’s identity as the Motor City and framed as a brand that could travel far beyond Michigan.

The label’s mythology tends to emphasize discovery: the teenage prodigies, the vocal groups, the dancers drilled into sync. But Motown’s origin story is also an operations story—distribution hurdles, studio time, publishing rights, radio relationships, training regimes, and the internal governance Gordy called “quality control.”

To tell Motown’s founding is to follow Gordy’s journey as a builder: a former assembly-line worker who borrowed industrial logic and applied it to culture. His product was not just music. It was mobility—social, geographic, commercial. And his throughline is audible in the records that marked Motown’s ascent: Marv Johnson’s “Come to Me,” the Miracles’ Hi… We’re the Miracles, the Supremes’ “Baby Love,” the Temptations’ “My Girl,” the Four Tops’ “Reach Out I’ll Be There,” Marvin Gaye’s “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” the Jackson 5’s “I’ll Be There,” and Stevie Wonder’s “Superstition.” Each is a mile marker in a story about ownership and ambition—about a founder determined to prove that a Black-owned company could dominate the mainstream without asking permission.

Berry Gordy before Motown: Learning the price of talent

Berry Gordy Jr. did not stumble into record-making. He arrived with a set of lessons that the entertainment industry forces on Black creatives—often quickly and often harshly. In Detroit, a city whose identity was built on production lines and migrant ambition, Gordy grew up in a household that treated self-reliance as both philosophy and survival. The Gordy family’s later role in financing Tamla is sometimes described as a charming detail, but it is more accurately read as an early expression of Motown’s economic theory: pooled resources as a countermeasure to exclusion. Motown Museum’s account of Gordy’s start emphasizes the family cooperative (“Ber-Berry Co-op”) and Gordy’s intention to apply auto-plant principles to making records.

Gordy’s own apprenticeship was varied—boxing, factory work, and a long stretch of learning how the music business distributes credit versus cash. The assembly line mattered not because it romanticizes blue-collar grit, but because it gave Gordy a blueprint for repeatability. A factory turns individual skill into consistent output by standardizing processes and enforcing quality gates. Gordy’s later Motown model—centralized songwriting, tightly controlled production, performance coaching, and weekly release decisions—would mirror that logic so closely that contemporaries and historians repeatedly describe Motown as a “hit factory.”

The other decisive lesson arrived through songwriting. In the 1950s, Gordy wrote and produced material in a marketplace where Black writers could create cultural currency while receiving limited long-term security. Songwriting offered him proximity to success, but it also revealed how little protection a creator had without ownership of publishing and masters. Those patterns—who controlled rights, who owned catalogs, who benefited from the afterlife of a song—convinced Gordy that the industry’s default structure was not simply unfair but engineered for extraction.

This is where Motown’s origin becomes more than a tale of talent scouting. Gordy’s founding impulse was structural. He envisioned an institution that could train artists, control production, and retain ownership—an integrated business capable of competing with major labels on their own terms. When the Washington Post later framed Motown as a form of cultural diplomacy—music that crossed boundaries Gordy believed were thinner than politics made them seem—it also implied the prerequisite for such diplomacy: Gordy had to build an export apparatus sturdy enough to carry it.

By the time he borrowed that $800, Gordy was not betting on a single act. He was betting on a system.

The founding: Tamla, the first release, and the proof of concept

On January 12, 1959, Gordy used that family loan to launch Tamla Records, later adding the Motown label and incorporating what would become the Motown Record Corporation. The date matters not because it sanctifies an anniversary, but because it marks the moment Gordy chose institutional risk over creative employment. Starting a label meant taking responsibility for the parts of the music business most artists never see: manufacturing records, negotiating distribution, financing studio time, persuading radio to listen, collecting royalties, and surviving the gap between a record being made and a record being paid for.

The founding story also tends to begin with a building. Gordy’s purchase of the West Grand Boulevard property—later branded Hitsville U.S.A.—became the physical manifestation of his ambition. Motown Museum describes how he moved his family into the upper unit and ran the business below, with Studio A in a converted space at the back of the house. A city encyclopedia entry from Detroit’s historical institution similarly emphasizes the $800 loan, the founding of Tamla, and the establishment of Hitsville as headquarters.

But the most revealing “first” in the Motown story is not the building—it’s the record that had to make the whole venture feel real.

“Come to Me”: Marv Johnson and the beginning of the Motown wager

If Motown became famous for polishing stars, Marv Johnson’s “Come to Me” is the sound of the label trying to stand up without falling. Accounts of the single consistently describe it as Motown’s first release and a foundational moment for Gordy as both entrepreneur and songwriter. The Michigan Rock and Roll Legends entry adds operational detail that reads like a parable: the song was recorded at United Sound Systems in Detroit, pressed at American Record Pressing in Owosso, and Gordy and Smokey Robinson drove through a snowstorm to pick up the first boxes of singles.

That image—founders retrieving inventory themselves—captures the fragility of the early enterprise. “Come to Me” was not simply art; it was product. It required manufacturing logistics and cash flow management. It required sales channels. It required the founder to be willing, literally, to carry the goods.

The single also reveals Gordy’s early dual identity: executive and creative. He wasn’t merely signing artists; he was shaping material. And he was learning, in real time, how distribution limitations could restrain a label’s ambitions. The early need to partner, lease, or otherwise maneuver for national reach would reinforce Gordy’s desire for full vertical integration—control of creation, manufacture, marketing, and monetization.

In that sense, “Come to Me” is the first Motown record not only chronologically but philosophically. It is the beginning of a business story told in three-minute increments: can a Black-owned label produce, distribute, and profit from its own music at scale? Gordy’s entire next decade would be an extended answer.

Hitsville and “quality control”: Industrial logic as cultural method

Motown’s early triumphs are sometimes treated like lightning strikes: Smokey Robinson’s pen, Diana Ross’s gaze, Marvin Gaye’s ache, Stevie Wonder’s genius arriving young and fully formed. But Motown’s defining innovation was procedural. Gordy built an internal governance system that treated hits as outcomes, not accidents.

Motown Museum’s own framing is unusually direct: Gordy would not “slap a Motown label on every song,” and artists and producers endured competitive company-wide meetings in hopes their songs would be approved for release. CBS, in a profile that explicitly uses Gordy’s language, notes that management met regularly to vote on releases, and Gordy called it “quality control.”

Quality control functioned like a factory gate. Songs were evaluated against market standards, not internal sentiment. This system did two things at once. First, it insulated Motown from the whims of a single producer or executive mood; decisions were socialized through discussion and competition. Second, it aligned the label toward crossover success. Gordy’s goal was not to dominate a niche “race records” market; it was to sell to the broadest possible audience—a strategy captured by the label’s self-description as the “Sound of Young America.”

The structure extended beyond releases. Artist development became formalized training—presentation, poise, choreography, stagecraft—so performers could appear on mainstream television and tour nationally with professionalism that resisted racist framing. Gordy’s own account, as summarized by the museum, is telling: he envisioned a process by which a kid could enter as an unknown and exit as a polished performer.

This is where Hitsville became more than an address. It became a campus. Writers, producers, musicians, and performers worked in close proximity, producing an internal culture with shared standards. The Guardian, reflecting on Motown’s identity and naming, underscores Gordy’s ambition beyond Detroit while still wanting the label’s name to signal its roots in the Motor City. That balance—local discipline, global ambition—became Motown’s signature.

And it is in this operational context that the first truly Motown-era artifacts emerge: records that don’t merely succeed, but reveal the system’s capacity to replicate success.

The Miracles define the early template: Hi… We’re the Miracles

Motown’s first era had a face, and it was Smokey Robinson’s. Before Motown dominated with girl groups and stadium-ready charisma, it established its identity through a vocal group sound refined into pop architecture. The Miracles—originally the Matadors—were among Gordy’s earliest successes, and their debut album, Hi… We’re the Miracles, carries institutional weight: it is routinely described as the first album released by the Motown Record Corporation on the Tamla label.

The album matters partly because it signals Gordy’s intention to build catalogs, not just singles. Albums create long-term assets: deeper publishing revenue, touring identity, and a narrative around an act. They also indicate that a label has the infrastructure to sustain production schedules and marketing beyond one release cycle. If “Come to Me” is the proof that Tamla could exist, Hi… We’re the Miracles is evidence that Motown could behave like a real company.

It also illustrates Motown’s early musical balancing act. The record blends doo-wop inheritance, upbeat R&B, and balladry—an audible prototype for the Motown Sound before it fully crystallized. Wikipedia’s summary emphasizes the record’s role in defining the Motown Sound and establishing Robinson and Gordy as songwriters. Smokey Robinson’s own official site frames the album similarly, calling it the first Motown album and an influential foundation for the developing 1960s Motown approach.

The early Miracles era also teaches a quieter lesson about Gordy’s management style. Motown was a family in rhetoric, but a corporation in practice. Gordy recruited and nurtured talent while centralizing authority. That tension—between intimacy and control—would later become a recurring theme as artists matured, demanded autonomy, and ran into the constraints of the very system that elevated them.

For now, though, the Miracles represented what Gordy needed most: reliability. A stable act. A creative partner. A sound that could travel.

The Supremes and the crossover machine: “Baby Love”

If Motown’s early years are about building capacity, “Baby Love” is the moment the capacity proves it can dominate the center of American pop. Released September 17, 1964, written by Holland–Dozier–Holland and recorded at Hitsville’s Studio A, “Baby Love” became one of the label’s defining crossover records, reaching No. 1 on the Billboard pop chart and topping the U.K. chart as well.

The record is important not only because it was successful, but because it was engineered to be successful. The Wikipedia entry notes that, at Gordy’s insistence, the production team crafted it to resemble the group’s prior hit—evidence of Motown’s deliberate approach to product-market fit. This is not artistic laziness; it is business logic. Gordy was building a repeatable hit pipeline, and a follow-up single was part of maintaining momentum, radio trust, and chart dominance.

“Baby Love” also reveals Motown’s intricate internal division of labor: the writers and producers (Holland–Dozier–Holland), the house band (the Funk Brothers, whose role in creating the Motown Sound is widely discussed), and the performers, trained to project consistency and charm across television and touring circuits. The Supremes’ rise became a template for turning local talent into global commodity—an institutional promise Gordy had essentially printed above his front door.

More subtly, “Baby Love” demonstrates Motown’s approach to assimilation and resistance. The record is not explicitly political, but its existence as mainstream dominator was political in effect: it put Black women at the center of global youth culture. It was “clean” enough for wary gatekeepers and still unmistakably rooted in Black musical sensibility. Gordy’s strategy—sell excellence that cannot be denied—was a wager that the market could be made to outvote prejudice.

By the time “Baby Love” surged internationally, Motown was no longer merely participating in pop. It was shaping it.

Tenderness as a brand asset: The Temptations’ “My Girl”

Motown’s genius was not just in manufacturing excitement but in packaging emotional universals with unmistakable identity. The Temptations’ “My Girl”—released in late 1964 and reaching No. 1 in 1965—illustrates how Gordy’s system could turn intimacy into a commercial engine. The song was written and produced by Smokey Robinson and Ronald White, and it became the Temptations’ first No. 1 single.

“My Girl” functions as an anchor for Motown’s mid-1960s maturity: the label is now deep enough that its artists generate hits for one another. Smokey Robinson is not only an act; he is a production node, shaping the destinies of fellow performers. That internal circulation of talent—writers writing for singers, singers learning from other singers—was a key part of Motown’s scalability. The company was a talent ecosystem, not a collection of isolated stars.

The record also demonstrates Motown’s capacity to make Black male tenderness feel inevitable in mainstream culture. “My Girl” is not a protest song, but it is a corrective to stereotype. In a country that often rendered Black men as threat or labor, Motown offered romance as public identity. It was a form of cultural persuasion, executed through melody and arrangement rather than argument.

At the institutional level, “My Girl” is also an example of Gordy’s brand promise: emotional clarity plus production excellence. Motown’s quality control meetings existed to ensure that songs like this—accessible, memorable, and durable—were the ones that reached the market.

By the time “My Girl” became a signature song, Motown had proven it could create not only hits, but standards—records that could outlive their release date and become part of American emotional vocabulary.

Drama at full volume: The Four Tops’ “Reach Out I’ll Be There”

Released August 18, 1966, written and produced by Holland–Dozier–Holland, “Reach Out I’ll Be There” is the sound of Motown leaning into urgency—romantic on the surface, near-spiritual in delivery, and engineered for maximum emotional lift. The record went to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 and the R&B chart.

If “My Girl” demonstrates Motown’s tenderness, “Reach Out” demonstrates its command of intensity. Levi Stubbs’ vocal arrives like a rescue mission. The production uses dramatic orchestration and rhythmic insistence to turn a love song into an anthem of reassurance. For Gordy, this was a commercial strength: Motown could deliver different emotional temperatures while preserving the brand’s sonic signature.

But “Reach Out” also speaks to Motown’s strategic relationship with the era’s turbulence. The mid-1960s were saturated with civil rights conflict, political violence, and profound public stress. Motown’s most famous records rarely named these realities directly; instead, they often translated collective unease into personal narratives—longing, devotion, heartbreak, reassurance. In that sense, “Reach Out” functioned as a kind of mass-appeal balm: a record that could sound like comfort without announcing itself as commentary.

This was, again, Gordy’s wager: that music could cross boundaries by meeting people where they were emotionally. The Washington Post’s later description of Motown as a kind of boundary-crossing diplomacy resonates here: Gordy believed people were “more alike than different,” and Motown’s greatest records treated that sameness—desire, fear, joy—as market truth.

“Reach Out” marks the moment Motown’s hit factory isn’t just efficient; it’s cinematic.

The system meets its limits: Marvin Gaye and “I Heard It Through the Grapevine”

Motown’s internal discipline produced domination, but discipline can also become constraint. Marvin Gaye’s “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” is a case study in how market demand—and artist evolution—began to press against Gordy’s centralized control.

The song, written by Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong, had already been released successfully by Gladys Knight & the Pips in 1967. Gaye’s version was recorded earlier but initially withheld as a single, then appeared on his 1968 album In the Groove, where radio DJs began playing it heavily. Accounts emphasize that Gordy ultimately agreed to release it as a single because DJs made it unavoidable.

The details matter because they invert the Motown model. Instead of quality control determining what the market would hear, the market effectively forced Motown’s hand. Gordy’s internal gatekeeping—normally a strength—became a liability when it misread demand. The episode is often cited as a pivotal example of how Motown’s centralized decision-making could clash with the emergent autonomy of its artists and the preferences of radio culture.

Gaye’s “Grapevine” became a massive commercial triumph, topping the Billboard pop chart for seven weeks and becoming one of Motown’s signature records. But culturally, it also signaled a shift. The tone is darker—paranoia, suspicion, psychological unrest—more reflective of late-1960s complexity than earlier Motown innocence. It hinted that the audience was ready for deeper textures and that artists like Gaye were ready to outgrow purely manufactured roles.

In Motown’s founding myth, Gordy is the all-seeing architect. “Grapevine” complicates that myth. It shows that even the best system must, eventually, listen.

Scale as spectacle: The Jackson 5 and “I’ll Be There”

By 1970, Motown had become something larger than a record label. It was a global entertainment engine—capable of turning youth into an export commodity and nostalgia into currency. The Jackson 5’s “I’ll Be There,” released August 28, 1970, is Motown’s apex of scale and perhaps the clearest example of Gordy’s ability to engineer superstardom. The song was co-written by Gordy, produced by Hal Davis, and became the group’s fourth consecutive No. 1 hit—an historic chart feat.

“I’ll Be There” also illustrates Motown’s geographic transition. The record was recorded at Hitsville West in Los Angeles, a signal of Gordy’s expanding ambition and Motown’s evolving footprint. If Hitsville Detroit represented the factory model—tight proximity, constant output—Los Angeles represented an entertainment horizon: film, television, celebrity, and a broader talent ecosystem.

The song itself is structured as a promise. Michael Jackson’s voice—still youthful but already commanding—turns reassurance into spectacle. Motown’s earlier love songs often sounded like private vows; “I’ll Be There” sounds like a public contract, delivered with stadium intent. It is also a bridge between Motown eras: the polished vocal-group tradition updated into something almost cinematic, with Gordy’s signature instinct for what would translate broadly.

Yet “I’ll Be There” also belongs to Motown’s recurring tension between cultivation and control. The Jackson 5 were a corporate triumph, but their later trajectory—like that of other Motown acts who sought autonomy—would raise questions about creative freedom, compensation, and the costs of being manufactured into icons. Motown could make stars. The harder task was holding them once they realized their own power.

Reinvention through autonomy: Stevie Wonder’s “Superstition”

If the Jackson 5 represent Motown’s command of spectacle, Stevie Wonder’s “Superstition” represents Motown’s capacity to survive by evolving. Released October 24, 1972 on Tamla as the lead single from Talking Book, “Superstition” reached No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 in January 1973.

The record is important because it announces a new relationship between Motown and its artists: less finishing school, more partnership with auteurs. “Superstition” is funk-forward, rhythmically aggressive, and technologically adventurous, reflecting Wonder’s control over the shape of his sound. It belongs to an era when Motown’s artists—Wonder most notably—were pushing beyond the label’s earlier formulas into music that carried more pronounced personality and experimentation.

This shift coincides with Motown’s broader institutional transition, including its Los Angeles relocation. LAist describes the 1972 move as strategic, tied to ambitions in film and television and a belief that Los Angeles was a strong base for expanding Motown’s reach. But transitions come with costs. A Washington Post retrospective about the Funk Brothers—Motown’s Detroit-era studio musicians—describes how, when Motown moved, the musicians learned of it only after arriving at Studio A to find a note that sessions were canceled. The move, in other words, was both corporate strategy and cultural rupture.

“Superstition,” then, is a pivot-point record. It demonstrates that Motown could remain commercially dominant without being trapped in its own origin story. It also reveals that Gordy’s most durable gift to the culture may have been the institution that allowed artists like Wonder to mature into world-shaping creators—sometimes by stretching beyond Gordy’s original model.

Motown’s founding legacy: What Gordy built that charts can’t measure

Motown is often summarized through numbers—hits, chart placements, the sheer density of classics. But its most radical achievement may have been institutional: a Black-owned company that treated Black talent as central, investable, exportable, and permanent.

The Detroit Historical Society’s encyclopedia entry emphasizes the founding mechanics—$800 loan, Tamla’s creation, the later addition of the Motown label, and Hitsville as headquarters. Motown Museum’s narrative adds the personal texture: Gordy living upstairs, building the company downstairs, applying assembly-line principles to culture, envisioning transformation from unknown to polished star. The Guardian adds a branding insight: Gordy’s naming strategy—Motown as a familiar-sounding tribute to Detroit—was a deliberate choice that made the label’s roots legible even as it chased global reach.

And yet, Motown’s story cannot be told honestly without acknowledging its tensions. A hit factory can be a family for some and a machine for others. The same quality control that ensured excellence could also delay or deny artists’ impulses. “Grapevine” is the clearest example of the system being corrected by the outside world. The move to Los Angeles—strategic and ambitious—also produced losses, including the displacement and invisibility of Detroit-era musicians whose labor shaped the sound.

Still, the throughline is unmistakable. From the fragile entrepreneurship of “Come to Me” (records hauled through snowstorms) to the refined institutional voice of Hi… We’re the Miracles, to the global domination of “Baby Love,” the tenderness of “My Girl,” the urgency of “Reach Out,” the internal friction revealed by “Grapevine,” the mass spectacle of “I’ll Be There,” and the reinvention announced by “Superstition,” the Motown story is a story of evolution driven by Gordy’s constant recalibration.

Motown did not merely reflect America’s youth. It helped define what youth sounded like—who could embody it, who could sell it, and who could own it. That was Berry Gordy’s founding act: not the discovery of talent, but the construction of a Black-owned system capable of turning talent into history.