By KOLUMN Magazine

In the early 1970s, American public television briefly hosted something that now feels almost impossible: a nationally broadcast space where Black artists, thinkers, and political voices were not asked to translate themselves for whiteness, not asked to soften the edges, not asked to keep the peace. SOUL!—created and produced by Ellis Haizlip for WNET (then WNDT/WNET) and distributed through NET/PBS—was a weekly repudiation of the era’s media gatekeeping, a program that treated Black culture as both aesthetic achievement and political evidence.

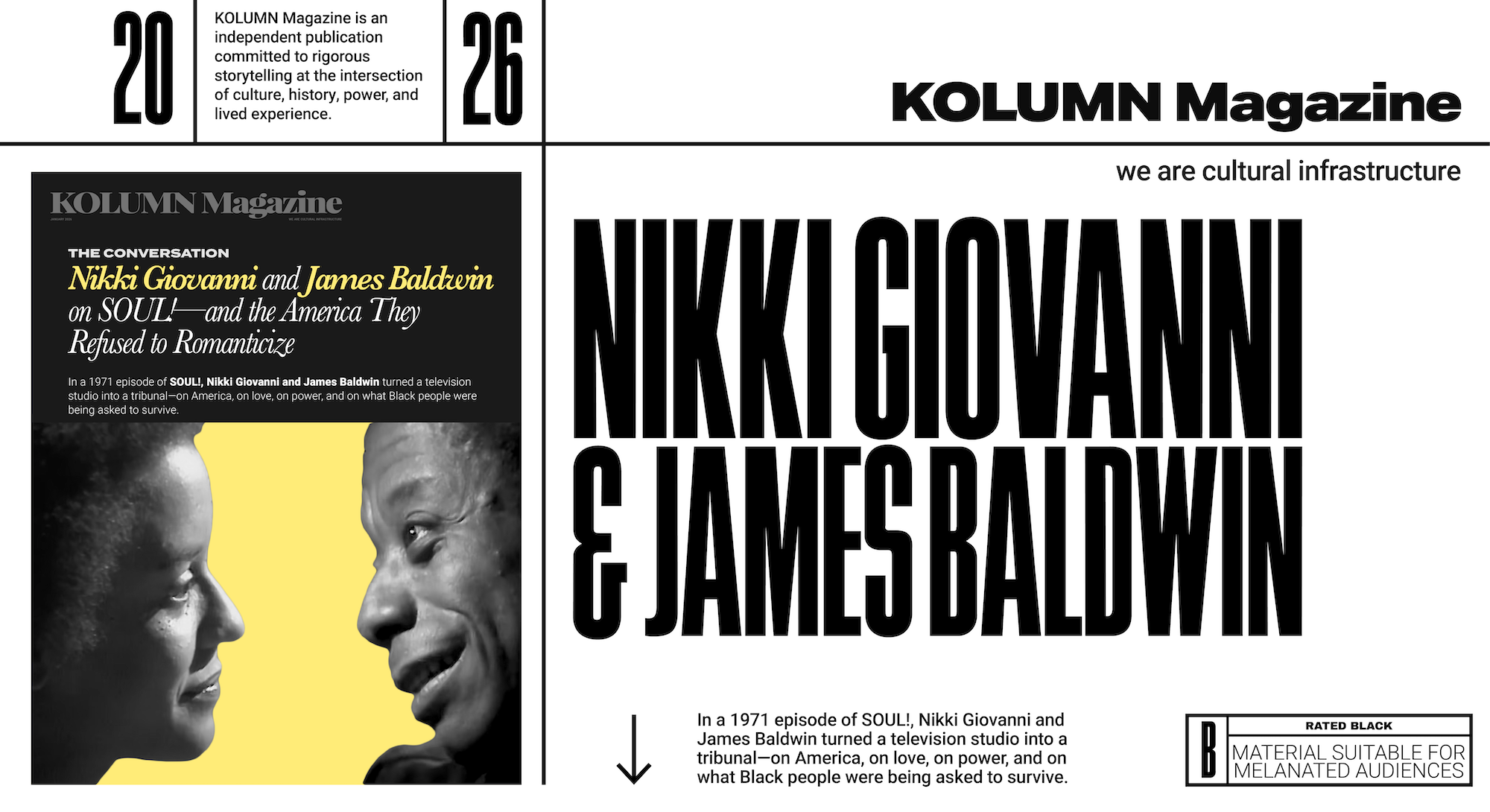

Among its most enduring installments is the two-part, London-taped exchange between Nikki Giovanni and James Baldwin—often circulated simply as A Conversation. The American Archive of Public Broadcasting describes it plainly: Baldwin is interviewed by “the young black poetess Nikki Giovanni,” and the two discuss life for Black men and women in a “white dominated society.” In the transcript, Haizlip frames what viewers are about to witness: “two very gifted and much loved black writers thinking questioning and exchanging ideas,” filmed in London and edited for broadcast.

That framing matters, because the Giovanni–Baldwin dialogue does not behave like an interview. It behaves like an argument among kin—urgent, unfinished, intimate enough to be uncomfortable. Giovanni’s questions carry the impatience of a younger generation watching the victories of civil rights harden into new kinds of containment. Baldwin’s answers carry the scar tissue of a longer timeline: he is nearly fifty, he says, and must “avoid sounding…defensive” even as he tries to answer honestly.

London, too, matters. Both speakers are American, but the conversation is staged outside the United States, where Baldwin had long sought enough distance to write—and enough clarity to refuse the nation’s myths. Early in the exchange, Giovanni asks him directly why he moved to Europe. Baldwin answers with an origin story that is also an indictment: he first went to Paris in 1948 because he was trying to become a writer, and in America he could not find “a certain stamina…a certain corroboration” that he needed—because, in his youth, no one had told him a Black writer could exist.

From there, the dialogue widens into a study of systems: how a country manufactures “standards” that invade the psyche; how capitalism and race braid together; how patriarchy mutates under racial terror; how movements fracture when they confuse performance for transformation. What Giovanni and Baldwin do—without ever formalizing it—amounts to a social theory of the everyday. Their subject is not only what America does to Black people, but what those pressures do inside Black life: inside households, inside love, inside language, inside the self.

What follows is a longform examination of that 1971 conversation—grounded in the transcript, contextualized within the period’s racial, economic, and political realities, and situated within the standing of Giovanni and Baldwin as public intellectuals whose work was already shaping how America understood itself.

Standing and Storm: Who Giovanni and Baldwin Were in 1971—and What the Era Was Doing to Everyone

By the time SOUL! taped the conversation, James Baldwin was not merely a celebrated author; he was a moral instrument the United States both depended on and punished. Decades earlier, he had begun publishing essays and fiction that refused America’s innocence. By the early 1970s, he was widely regarded as one of the nation’s preeminent writers—an artist whose sentences carried courtroom force. He had also become, almost against his will, a civic witness: a man called upon to interpret America’s racial crisis, to speak after assassinations, to argue with politicians, to translate grief into language sturdy enough to survive the news cycle.

Baldwin’s personal biography, by 1971, had already acquired the shape that later documentaries and museum narratives would emphasize: Harlem childhood; the church; early literary promise; exile and return; the psychic toll of American racism; a lifelong insistence that the “Negro problem” was, in truth, a white American problem of identity and power. The National Museum of African American History and Culture situates a crucial turn in 1968, when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated—an event that left Baldwin searching for a place to heal and to keep working. A PBS American Masters timeline similarly notes Baldwin’s movements and work across these years, emphasizing how the era’s violence and political upheaval reshaped his life and output.

In the transcript, Baldwin offers his own chronology with the authority of memory. He tells Giovanni he first moved to Europe in 1948, “trying to become a writer,” because he could not find the corroboration he needed in his American surroundings—because the very category “Black writer” had been withheld from him as imaginable. Later, he adds that something “ended” or “something else began” after King was murdered; he spent “a long time in limbo,” and in 1971 he is “based in the south of France.” The point is not tourism. It is survival: distance as a method for seeing clearly, and clarity as a method for not being destroyed by what one sees.

Nikki Giovanni arrives in that London studio from a different angle of the same storm. In 1971 she was young—around her late twenties—yet already established as a literary force associated with the Black Arts Movement: a poet whose voice traveled easily between page, stage, and television. Her early collections—Black Feeling, Black Talk (1968) and Black Judgement (1968)—had made her a public figure: accessible, political, intimate, and unafraid of plain speech. Giovanni’s official bibliography foregrounds how quickly her work accumulated across the late 1960s and early 1970s. The SOUL! introduction in the transcript reinforces her stature by listing her publications and editorial work, presenting her not as an ingénue but as a writer with a growing body of influence.

The pairing matters: Baldwin, the older novelist-essayist shaped by mid-century America’s betrayals; Giovanni, the younger poet shaped by Black Power’s urgency and the movement’s internal contradictions. In their exchange, you can hear the era’s generational argument: Giovanni pushing on the intimate failures she sees around her; Baldwin insisting the failures are real but inseparable from the machinery that manufactures them.

That machinery, in 1971, was not abstract. The formal victories of the civil rights era had not resolved the core economic and political structure of inequality. Northern cities wrestled with segregation by neighborhood, school district, and policing practice. Deindustrialization was beginning to bite. The Vietnam War continued to reorder national priorities, budgets, and grief. The federal government’s posture increasingly leaned toward “law and order,” a phrase that often served as a polite synonym for suppressing Black dissent.

The year 1971 also sits amid flashpoints that clarify what Baldwin means when he calls the pressures “inhuman.” In September, the Attica prison uprising in New York would expose the conditions of incarceration and the state’s willingness to meet demands for human treatment with lethal force. It is difficult to overstate what Attica represented: not merely a prison event, but a national mirror held to carceral policy, racial hierarchy, and political legitimacy.

At the same time, Angela Davis’s prosecution and imprisonment had become a global cause célèbre. Davis had been charged in 1970 and held while a broad movement rallied around “Free Angela.” Her case symbolized how the state could reframe political radicalism as criminality—a point Giovanni and Baldwin orbit as they discuss power and the narratives that discipline Black life.

And in June 1971, President Richard Nixon delivered a special message to Congress on drug abuse prevention and control—part of the policy and rhetorical environment that would later be remembered as foundational to the “war on drugs.” Whether one emphasizes treatment rhetoric or enforcement outcomes, the period reflects a growing state focus on policing social disorder—often at the expense of structural remedies for poverty and racialized exclusion.

This is the atmosphere Giovanni and Baldwin bring into the studio: a moment when America is simultaneously congratulating itself for civil rights progress and refining new instruments of containment—economic, carceral, and cultural. It is also a moment when the Black freedom struggle is confronting internal questions of leadership, ideology, gender, and strategy. Baldwin names one version of this problem with blunt clarity: much of what passes for “black militancy,” he suggests, is “fashion,” while something more valuable—an underlying “impulse”—must be preserved. Giovanni, listening, is not persuaded into silence. Her questions imply: even if militancy is fashion, what do we do about the casualties created inside Black relationships?

That is the central tension of the London conversation: two writers agreeing that America is in moral crisis, while debating how that crisis metastasizes inside Black life—and how Black people might refuse to inherit the nation’s emotional and gendered violence as their own.

“You Become a Collaborator”: Their Diagnosis of Black Life in America

One reason the Giovanni–Baldwin exchange remains so watchable is that it treats “Black life in America” as something more complex than suffering—and more complicated than triumph. Both speakers refuse the easy story in which Blackness is only victimhood. But they also refuse the story in which resilience becomes an alibi for ongoing extraction.

Early in the conversation, Baldwin offers a line that functions like a thesis: the world does something to you long enough and effectively enough that “you begin to do it to yourself,” becoming “a collaborator…an accomplice of your own murderers” because you start believing what they believe—about whiteness, about Black shame, about what counts as life. The brilliance of this claim is that it identifies an interior battleground. Racism is not only a set of laws or acts; it is a pedagogy. It teaches the oppressed to police themselves.

Baldwin makes this pedagogy concrete. He describes how Black children are forced into parody: scrubbed, shining, trained to behave as if respectability might purchase safety. The training is physical and psychic: the body made stiff, the spirit made anxious, the self split between what it is and what it must perform to survive. In Baldwin’s telling, the tragedy is not only that this performance fails to secure protection; it also robs the performer of ease—of dance, of movement, of joy, of the right to be unguarded.

Giovanni’s lens is more domestic, more immediate. She is attentive to what Baldwin sometimes renders as “history” but what she experiences as a daily social climate: how fear and economic precariousness show up in Black neighborhoods, in relationships, and in the emotional availability of men. When she talks about Black men “sliding away” from women—arms crossed, unlovable, withholding love—she is not describing a theory; she is describing a feeling of abandonment that she believes is widespread.

Baldwin does not deny the pattern. Instead, he tries to name the mechanism that produces it. His most harrowing passage concerns his father: a man raising nine children on $27.50 a week, enduring degradation at work, unable to protest because his children must eat. Baldwin narrates the slow destruction of “manhood,” hour by hour, day by day, under conditions where a man is treated with contempt in public and then returns home carrying the humiliation like a live wire. He calls the pressures “inhuman,” and explains how love between husband and wife is eroded—not by personal failure, but by relentless external assault.

Here, Black life in America emerges as a set of forced translations. A father cannot tell a child what is being done to him, because the truth is too ugly and too destabilizing. Baldwin imagines the impossible explanation: a boss calling him a slur, quitting, and then facing the child’s empty stomach. The father remains silent, and the child misreads the silence as powerlessness. The tragedy expands: children begin to despise their fathers, not understanding the system that has trained the father into a constrained role.

Giovanni’s response is crucial: she understands the systemic pressure, but she insists on naming how that pressure can be displaced onto women—how a man brutalized “somewhere” can come home and reenact brutality in the place where he has the most social permission to do so. She is not satisfied with explaining behavior; she wants accountability inside intimacy.

This is where the conversation becomes less like an interview and more like a family argument about inheritance. Baldwin wants Giovanni to see that Black life’s private crises are inseparable from what America has done: the economic constraints, the racial humiliations, the theft of stability. Giovanni wants Baldwin to see that even if those forces are causal, they do not absolve harm done inside Black homes and relationships. In effect, they are debating a question that still haunts American discourse: when oppression explains behavior, what do we do with responsibility?

They also share an unusual clarity about class. Giovanni acknowledges her own distance from the deepest poverty, noting she “had enough to eat,” which complicated her understanding of certain experiences she nonetheless observes. Baldwin similarly insists that the nation’s “standards” are not merely cultural—they are commercial, profit-driven, built on commodities and exploitation. Black life, in that view, is lived inside an economy that was designed from the beginning to monetize Black bodies and then monetize Black deprivation.

In London, they are describing America as a place where Black people are asked to build selves, families, and futures while standing on terrain designed to collapse beneath them. Their disagreement is not whether this is true. Their disagreement is where, inside that collapsing terrain, Black people can still choose one another—without reproducing the country’s violence in miniature.

The Struggle for Racial Justice: From “Power” to Language to the Invoice America Keeps Dodging

If the first half of the conversation diagnoses Black life’s private injuries, the second half escalates toward an argument about what racial justice requires beyond symbolism. Baldwin and Giovanni are both skeptical of slogans; both are wary of movements that become performances; both understand that the struggle is not simply to be included in America, but to transform what America is.

Baldwin repeatedly returns to a notion that can sound abstract until he makes it practical: power. Giovanni uses the term readily; Baldwin sometimes prefers “morals,” and they circle the truth that the words are functionally aligned. What matters is not the label but the content: the capacity to effect change, to protect children, to build conditions in which life is livable.

The transcript reveals Baldwin’s insistence that changing conditions requires changing thought, and changing thought requires changing language. “You have to begin to shift the basis of the language,” he tells Giovanni, because “the way people speak is also the way they think.” This is more than rhetorical strategy; it is a theory of consciousness. If America’s language has been built to naturalize hierarchy—Black inferiority, white innocence, economic inevitability—then liberation requires a linguistic break: a refusal to let the master’s grammar define the terms of reality.

The conversation’s London setting intensifies this point. Speaking outside the United States, Baldwin is not less American; he is, arguably, more precise about America’s claims. In one of the transcript’s most quoted stretches, he offers a paradox: Black people have recognized they are “not Americans,” and yet they are also “the only true inheritance of the place.” The statement is destabilizing by design. It rejects assimilation as the endpoint, while asserting ownership that cannot be legislated away. It reframes racial justice not as access to America’s promise, but as a confrontation with America’s origin and its debts.

Debt is the recurring metaphor. Baldwin’s “bill” language is not simply poetic. It is a moral accounting: slavery and exploitation created a balance sheet, and America has tried to avoid payment by demanding sympathy for the anxieties of those who benefited. In the transcript, he describes white power training Black fathers into servitude and expecting the structure to reproduce itself forever—then says, essentially, the invoice has arrived.

Giovanni’s role in this section is not to contest the indictment; it is to test what it means in practice. She pushes on questions of economic power—land, money, access—because she understands that moral recognition without material transformation is a dead end. Baldwin agrees the crisis is commercial as well as racial: questions of land and money “reside in power,” and the ability to “effect” change matters more than formal ownership alone. Their back-and-forth resembles a policy argument conducted in philosophical terms: what does liberation mean if Black people remain structurally dispossessed?

The era’s wider context makes these questions urgent. SOUL! itself existed because mainstream media largely excluded Black political discourse—precisely why Haizlip’s show was such a radical intervention. Outside the studio, state power was flexing through policing and prosecution. The Attica uprising later in 1971 would become an emblem of what the state was willing to do to maintain control, and why “law and order” often meant “order maintained through violence.” Angela Davis’s imprisonment and the movement around her similarly signaled how racial justice activism could be reframed as threat—and how quickly the machinery of the state could mobilize to punish radicalism.

Baldwin also engages the era’s suspicion of protest that doesn’t transform the interior life. He warns against substituting “one romanticism for another,” implying that replacing white myths with Black myths—without deeper structural change—risks reproducing the same psychic trap. Even “Black is beautiful,” he cautions, can become dangerous if it is treated as a slogan rather than a lived ethic grounded in selfhood and relationships.

This is where racial justice becomes, for Baldwin, inseparable from a spiritual discipline. He is not invoking religion so much as integrity: the ability to love one’s children, to love oneself, to avoid becoming what one hates. Giovanni, coming from a movement era saturated in ideology, listens with partial agreement and partial impatience. Her focus remains: what do we do now, in the conditions we have, with the people we have, and the harm we are doing to one another?

Their convergence is clearest in their shared insistence that racial justice cannot be outsourced to time. Baldwin speaks of children as a “useful metaphor” that carries you past the despair of one moment into responsibility for the next. This future orientation functions as a rebuke to both cynicism and spectacle. If the struggle is only about winning the argument in 1971, it will fail. If it is about building a world children can inhabit without spiritual mutilation, it might still succeed.

Evolving Gender Roles: Love, Manhood, and the War Inside Black Intimacy

No portion of the Giovanni–Baldwin exchange feels more contemporary than its argument about gender. Not because it neatly aligns with today’s language—much of it does not—but because it demonstrates the enduring difficulty of holding two truths at once: that Black men have been historically brutalized by a racial order designed to deny them dignity; and that Black women have historically been asked to absorb the fallout, often inside the home.

Giovanni enters the gender discussion with impatience shaped by observation. She describes a pattern in which Black men insist on performative dominance—“in order for me to be a man you walk 10 paces behind me”—and she rejects the logic as futile. If a man’s sense of manhood depends on a woman diminishing herself, Giovanni argues, the woman can never get “far enough behind” to cure what is fundamentally insecure. It is an early articulation of what later feminist frameworks would formalize: patriarchy is not healed by compliance; it is sustained by it.

Baldwin’s response is careful. He does not defend the behavior as good. He reframes it as patterned, historical, and predictable. Some things that feel “new” to Giovanni are “not new” to him; he has seen how long such performances last, how they flare and fade, how they can become a “fashion.” He is, in effect, asking her to see the man performing dominance not as the ultimate enemy but as another casualty of a civilization that has systematically denied him stable dignity.

The conversation becomes most vivid when Giovanni brings pregnancy into the discussion. She describes a scenario: a man disappears when a woman becomes pregnant because he feels he cannot return without money for a crib—without being a provider in the narrow sense. Giovanni’s counter-argument is tender and cutting: the woman needs the man himself—his presence, affirmation, care—not an object purchased to validate masculinity. “Bring yourself,” she urges. She is arguing for a new definition of manhood: not possession, not provision-as-domination, but emotional presence and shared responsibility.

Baldwin largely agrees with her critique while refusing to treat it as simple. He suggests that the “standards of the civilization” into which Black people are born are imposed from outside first—and then internalized. If masculinity has been defined by economic dominance, and if Black men have been structurally denied stable access to economic power, then masculinity becomes a wound: something to defend, perform, and protect through whatever limited avenues remain—sometimes, tragically, by seeking control where control is possible (the household, the relationship).

This is precisely where Baldwin’s father story becomes a gender story. Baldwin describes watching his father’s “manhood” destroyed by work and humiliation; he describes the mother watching, the father watching her watch, and love being destroyed “hour by hour.” In that framing, the Black household is not the origin of violence; it is the arena where external violence is metabolized. Baldwin does not excuse the harm. He insists on understanding the engine.

Giovanni’s insistence is equally important: understanding the engine does not stop the harm. She is looking at Black women’s historical labor—emotional, domestic, economic—and recognizing that the movement’s rhetoric of liberation often failed to liberate women inside Black life. She does not say this as academic critique; she says it as lived frustration: men “not lovable,” men withholding love, men repeating the same syndromes their fathers lived.

Baldwin pushes the conversation toward possibility by returning—again—to children and to the necessity of making “new assumptions.” In one late passage, he rejects a system in which a woman’s “smile” becomes rent—where affection becomes prostitution, where survival requires self-erasure. He tells Giovanni, in effect, that they must work out “a new system,” because “as long as the assumptions are the same nothing will change.” This is Baldwin at his most practical: the revolution is not only in the streets; it is in the definitions people bring into love.

Their gender debate also reveals how the era’s public politics collided with private life. The early 1970s were a period when feminist movements were gaining visibility, but mainstream feminism often marginalized Black women’s experiences; simultaneously, Black liberation movements often marginalized gender critique in favor of racial unity, sometimes treating women’s concerns as distractions. Giovanni, in that studio, refuses to be told her concerns are secondary. Baldwin, for his part, refuses to let gender conflict become a mechanism for dividing Black people against each other—another “trap” that distracts from “one’s relationship to each other.”

This is what makes the exchange so enduring: neither speaker offers an easy villain. Giovanni is not satisfied with blaming white supremacy for everything if it leaves Black women carrying the weight alone. Baldwin is not satisfied with blaming Black men alone if it treats them as uncaused monsters rather than products of a deliberately brutal social order. The conversation models a difficult ethic: critique without dehumanization, understanding without indulgence, love without sentimental lies.

In 1971, on public television, they rehearsed a question that remains unresolved: What would it mean for Black liberation to include a transformation of intimacy—so that Black people do not merely survive America, but stop reenacting America’s logic in the most private rooms of their lives?

Coda: Why This Conversation Still Travels

The American Archive catalog entry emphasizes that the SOUL! special was taped in London and structured in two parts, a format that gave Giovanni and Baldwin room to think rather than perform soundbites. SOUL! itself was created to make space for Black cultural and political complexity on television, a mission later chronicled in retrospectives about Haizlip’s role and the show’s influence.

But the deeper reason the Baldwin–Giovanni conversation persists is simpler: it refuses closure. It does not end with a clean thesis. It ends with the sense that the speakers have told the truth as far as they can reach it—and that the rest must be lived.

Baldwin’s refrain returns, as it often does, to children and the future: the responsibility that carries you past a terrible Tuesday and a wretched Friday, toward the next generation that will inherit what you build or fail to build. Giovanni’s insistence returns, as it often does, to the immediate: love, presence, accountability, the daily ways people either abandon one another or choose one another despite the storm.

In London, they spoke like the future was listening. It still is.