KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

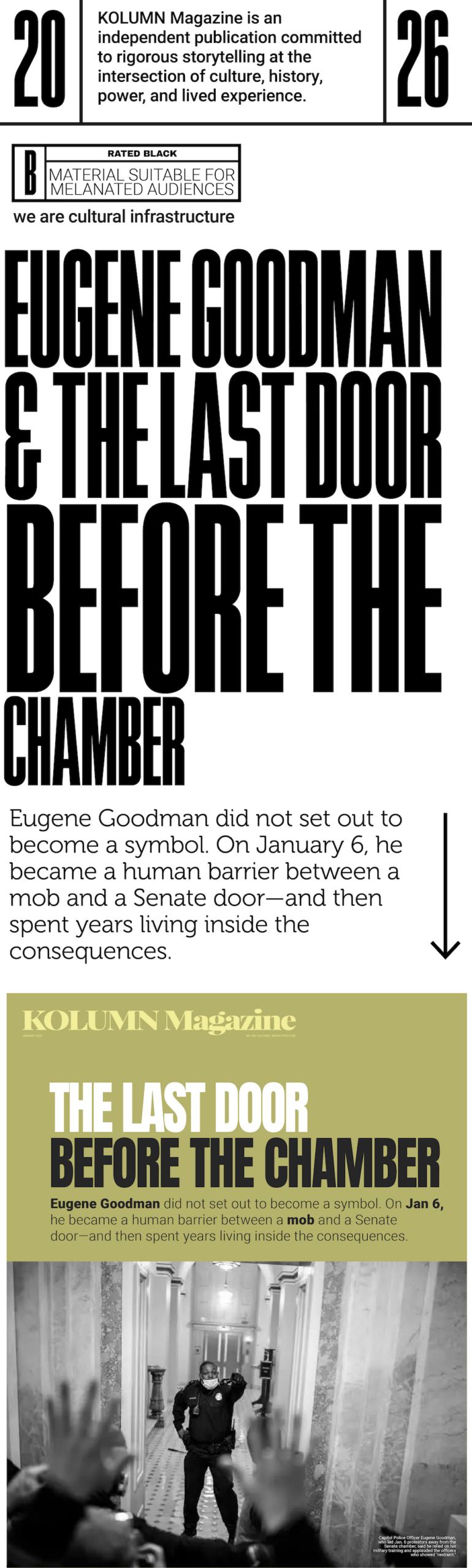

On the afternoon of January 6, 2021, the most consequential architecture in Washington is not the dome, the Rotunda, or the grand ceremonial staircases that tourists photograph as proof they were here. It is a tighter space—a corridor’s choke point, a landing, a turn—where decisions are made faster than language. In that compressed geography, the Capitol becomes less a monument than a working building under stress: doors, angles, blind spots, the physics of crowds.

That is where Eugene Goodman appears in the public imagination—first as a figure in widely shared footage confronting rioters inside the building, then as the officer who drew a surge of bodies away from the Senate chamber at a moment when evacuation was still underway. In one of the most replayed sequences of that day, he is both alone and not alone: a solitary uniform in the frame, carrying the accumulated weight of institutional authority, and also the immediate vulnerability of a person who can be cornered, grabbed, or crushed. The crowd’s energy is the opposite of order—unstable, adrenal, and loud. Goodman moves anyway, and keeps moving, turning the Capitol’s hallways into a kind of improvised funnel. In reporting and later commentary, his actions are credited with helping avert an even worse confrontation at or near the Senate’s doors. The Guardian described him as inducing the crowd to chase him away from the Senate chambers—baiting the mob’s momentum toward a safer direction.

A country that routinely demands myth is tempted to freeze that moment into a simple parable: one brave officer, one clever feint, one saved democracy. But Goodman’s story—like most stories of public servants who become symbols—resists the clean arc. Before he was a viral clip, he was an employee in a large, imperfect security institution. Before he was honored on a national stage, he was a Black man navigating an American profession where the uniform can grant power and invite contempt, sometimes in the same breath. And after the cameras turned him into a shorthand for courage, he had to return to work inside a building that would never feel the same.

This is an account of Eugene Goodman’s life and career journey as best it can be assembled from credible public records and reporting: his path through military service, the particular demands of the U.S. Capitol Police, the anatomy of the January 6 crisis that placed him at a hinge of history, and the public aftermath that made him both celebrated and constrained. It is also an account of the way the United States assigns meaning after violence—how a single officer can be elevated into a national icon while the underlying systems that failed on January 6 become the subject of political trench warfare.

One important precision at the outset: Goodman did not become widely known because he delivered extended, made-for-television testimony to Congress about January 6. The signature “testimony” in the public record is of different kinds—his presence in congressional proceedings when the Senate voted to honor him, the official language lawmakers entered into the Congressional Record praising his actions, and later his courtroom testimony describing the encounter in granular detail. The Associated Press reported that in June 2022 Goodman gave his first public testimony since January 6 at the trial connected to a man photographed carrying a Confederate battle flag inside the Capitol, describing being jabbed with a flagpole and then chased up a staircase. In other words: the most detailed sworn narrative from Goodman that the public has heard did not come from a congressional dais—it came from the judicial process that followed the attack.

If you want to understand who Eugene Goodman is, you have to hold all those “stages” at once: the stairwell, the Senate chamber, the courtroom, and the long institutional hallway afterward.

Washington, D.C., before the Capitol became a crime scene

Goodman is often described as a Washingtonian—born in 1980 and raised in the southeast section of the city, according to compiled biographical reporting. The basic fact matters not as trivia but as context: the Capitol is not only a national symbol; it is also local terrain. For D.C. residents, federal power is both backdrop and employer. The District’s political peculiarities—taxation without full representation, the presence of federal police forces layered atop local ones—create a civic atmosphere where government is a daily reality, not an abstraction.

Much of Goodman’s early life remains, by his own apparent preference, private. That privacy is part of the story. America has a long appetite for “origin stories,” especially for Black public figures and working-class heroes: the formative hardship, the mentor, the decisive turning point. But law enforcement officers, particularly those attached to sensitive federal facilities, often live within professional constraints that narrow what can be safely said. And Goodman, unlike many people pulled into the public spotlight, has tended to speak rarely and carefully—suggesting not a desire to capitalize on fame, but a preference to return to the job and let the footage stand.

Still, certain contours are clear. Goodman served in the U.S. Army from 2002 to 2006, including deployment with the 101st Airborne Division during the Iraq War, where he held the rank of sergeant. That experience—combat, leadership under stress, the discipline of responding to unpredictable threats—forms a plausible foundation for the “calm under pressure” that observers later projected onto him. It is one thing to say an officer remained composed; it is another to understand how composition is trained, rehearsed, and sometimes forced by circumstances that punish hesitation.

In January 2021 reporting, Military.com described Goodman as an Army veteran and framed his January 6 actions in the context of that background, noting his role as a Capitol Police officer who became newly prominent after redirecting rioters and then taking on a high-profile ceremonial role at the inauguration. It is tempting to read military service as a neat explanatory key—combat veteran equals bravery. But bravery is not a personality trait you carry like a badge; it is a behavior that emerges under conditions you cannot fully control. If military service taught Goodman anything useful for January 6, it was likely less about heroism and more about procedure: movement, positioning, threat assessment, and the practiced ability to keep functioning when adrenaline is screaming at your body to do something else.

After leaving the Army, Goodman joined the U.S. Capitol Police by 2009, according to compiled biographical accounts. The Capitol Police is often misunderstood by the public as a “security detail,” but it is a full law enforcement agency with its own complexity: patrol responsibilities, protective operations, intelligence, crowd control, and the unique demands of policing a political building that is also a workplace, a tourist site, and—on January 6—a target.

To work there is to live inside the contradiction of American democracy: the institution’s openness is part of its legitimacy; its vulnerability is part of its risk.

The U.S. Capitol Police: an institution built for threats, tested by politics

It is impossible to tell Goodman’s story without acknowledging the institution around him. The January 6 attack produced intense scrutiny of the Capitol Police’s preparation, command decisions, and staffing posture. Public discussion often collapses into the simplistic question—“Why weren’t they ready?”—but readiness is rarely a single switch. It is budgets and training cycles; intelligence interpretation; interagency coordination; the friction of deploying force in a politically sensitive environment; and, crucially, the inability of any agency to fully control the decisions of elected officials who shape security policy.

The January 6 story is also, unavoidably, a story about how law enforcement is read through partisan lenses. Some political actors have sought to minimize the violence; others have elevated it as an existential threat. These disputes matter because they shape how institutions adapt. In the years since, “January 6” has become not only an historical event but also a political instrument—invoked to justify new investigations, to defend prior ones, and to argue over accountability. Reporting on renewed congressional probes underscores how contested the narrative remains.

For an officer like Goodman, this politicization is not theoretical. It determines whether his actions are treated as evidence of institutional bravery or institutional failure; whether the day is remembered as “a riot,” “an insurrection,” “a protest,” or “a domestic terror attack”; and whether the public consensus supports reforms that might make the building safer or instead punishes the messengers.

In that environment, Goodman’s relative silence becomes legible: talk too much and you become a pawn; talk too little and you become an empty symbol others fill with their own meaning.

January 6, reconstructed: The job becomes improvisation

What is publicly known about Goodman’s movements on January 6 comes from video footage, investigative reconstructions, and later sworn testimony connected to prosecutions. ProPublica, in early reporting

drawing on Parler videos and other footage, highlighted the now-famous moment when Goodman led invaders up a flight of stairs and away from the Senate chamber, seen from the perspective of the mob. In The Guardian’s early account, Goodman is described as steering or inducing the mob away from the Senate chambers—language that captures both the tactical quality of his movement and the frightening reality that the “tactic” depended on the mob choosing to follow him.

This is the uncomfortable truth about that moment: Goodman could not control the crowd; he could only try to shape its momentum. He was not commanding; he was managing risk by becoming the focal point.

In the public imagination, this becomes “heroism.” In operational terms, it is closer to triage.

Later accounts sharpened the stakes. In Goodman’s first widely reported interview comments—summarized by Axios—he described that the day “could’ve easily been a bloodbath,” a blunt phrase that strips away the ornamental language of patriotism and puts the event back into the realm of bodily danger. A bloodbath is not a metaphor. It is the image of what happens when confined space meets rage, weapons, and panic.

The Senate chamber was not an abstract “objective” on January 6. It was a room containing elected officials, staff, and security personnel, operating under an evacuation timeline that depended on minutes. A single delay—one wrong turn by the crowd, one officer unable to move, one door breached earlier—could have changed who lived and who died.

And here the narrative turns, in part, on what Goodman did with seconds.

The landing and the push: A moment that became a national Rorschach test

At the center of the iconic footage is a confrontation: Goodman facing a surge, appearing to push at least one person back, then retreating in a manner that draws the crowd to chase him. In subsequent legal proceedings, this confrontation would be anatomized not for heroism but for evidence: who was where, who carried what, who struck whom, who crossed which threshold.

In June 2022, the Associated Press reported that Goodman testified at the trial of Kevin Seefried (and his son), with Goodman describing how a man carrying a Confederate battle flag jabbed him with the flagpole and then joined the group that pursued him. This courtroom setting matters. Unlike cable-news debates, a trial demands sequence, specificity, and accountability to the record. Goodman, under oath, was not performing patriotism; he was describing an assault inside the Capitol.

That detail—the Confederate flagpole used to jab an officer in the U.S. Capitol—feels almost too on-the-nose as American symbolism, a grotesque reenactment of the country’s unresolved past inside its most sanctified civic space. It is also, in practical terms, an example of how quickly objects become weapons in a crowd.

When Americans talk about January 6, they often argue about intent: did rioters mean to kill? did they mean to disrupt? did they mean to intimidate? But for an officer confronted in a corridor, intent is less important than capability. A jab can become a beating; a beating can become a shooting; a shooting can become a stampede. Crowd dynamics turn single acts into cascades.

Goodman’s decision—move, draw, divert—reads as a choice to prevent that cascade from reaching the Senate doors at the worst possible moment.

“Testimony” in the American system: Senate praise, courtroom fact, and the politics of honor

Goodman’s most visible relationship to Congress after January 6 was through congressional recognition and the congressional record, rather than a long, televised witness examination.

On February 12, 2021, the U.S. Senate voted by unanimous consent to award a Congressional Gold Medal to Eugene Goodman, and Goodman was present in the chamber, where senators gave him a standing ovation. The moment is not “testimony” in the strict legal sense, but it is a kind of civic statement: Congress identifying one officer’s actions as exemplary and doing so in the language of formal proceedings.

The Congressional Record around the Senate action includes language praising Goodman’s conduct and situating it as emblematic of the heroism displayed by officers defending the Capitol. In June 2021, congressional remarks again invoked “the courage of Capitol Police Officer Eugene Goodman” in the context of broader commemoration of officers who served and suffered that day. These are the places where Congress “speaks” about Goodman most formally: through the written record that becomes part of governmental memory.

But the most granular, sworn narrative from Goodman that the public can point to is his 2022 trial testimony. The Washington Post described that testimony as Goodman’s first time testifying in court publicly about leading rioters away from fleeing senators, recounting the chase through the Capitol. The AP’s version captures the same core: confrontation, flagpole, pursuit, stairwell.

If Congress honored him and the courts asked him to speak, the combination reveals something essential about how the American system metabolizes political violence: the legislative branch offers symbolic recognition; the judicial branch demands detail.

The two are not always aligned. Symbol can be unanimous even when accountability is contested.

The promotion and the inauguration: A public elevation, a private job

Goodman’s public status changed quickly after January 6. During President Biden’s inauguration in January 2021, Goodman drew attention not only as a hero of the prior week’s crisis but as a figure positioned close to power. Military.com reported that he was promoted and escorted Vice President Kamala Harris at the inauguration, a ceremonial and security role that placed him in a high-visibility frame.

Reports at the time described him as being named acting deputy sergeant-at-arms for the Senate (an acting role connected to Capitol security functions). In the public mind, the promotion became part of the “arc”: bravery rewarded with advancement. But promotions in security institutions can be complicated—part recognition, part operational need, part public messaging. After a crisis that exposed vulnerabilities, institutions often elevate individuals who symbolize competence, both to reward and to reassure.

For Goodman, this created a new double-bind. He became a visible representative of an institution under critique. Praise for him could coexist with condemnation of systemic failure, leaving him to carry admiration and anger at the same time.

The interview: Breaking silence without becoming a pundit

In January 2022, Goodman gave what was widely described as his first interview since January 6, speaking on a podcast and describing the events with a mixture of restraint and plain language. Axios highlighted his remark that the situation could have been a “bloodbath.” That word choice is notable because it is not the language of political messaging; it is the language of someone who witnessed what crowd violence can become.

This is an important tonal marker in Goodman’s public presence: he has generally not leaned into grandstanding. Where some public figures might transform sudden notoriety into a media career, Goodman’s limited commentary reads more like boundary-setting—acknowledging what happened without allowing himself to be absorbed into the entertainment layer that accretes around national trauma.

A Washington Post account of his first public comments framed them as his breaking a long silence, reinforcing the idea that he had been deliberately quiet. The quietness can be read as humility. It can also be read as professional constraint, or as a protective tactic—because a symbol who speaks becomes easier to attack.

Race, the uniform, and the mob: what America saw (and what it refused to say)

Any honest profile of Eugene Goodman must address the racial dimension of January 6—not as an overlay, but as part of the event’s lived reality for officers and for the Black Americans watching. The Capitol mob carried a stew of ideological signals—flags, slogans, conspiratorial myths—and within that stew was a recognizable strain of white grievance politics that has long treated Black authority as a provocation.

This is not abstract sociological inference; it is embedded in what officers reported experiencing that day, including racial slurs and dehumanizing language directed at law enforcement. While Goodman’s own public descriptions are limited, the broader record of the day includes officers describing racial abuse. (Harry Dunn’s written statement, for example, discusses racial slurs aimed at him; Dunn was among officers who testified publicly to Congress.)

Goodman’s stairwell moment is often described as tactical brilliance. But it is also a scene in which a Black officer becomes the object that a largely white mob chooses to chase—an American image with a long shadow. That shadow does not reduce his action to race; it deepens the risk he accepted. A crowd can be violent toward anyone. But American crowds have historically been particularly imaginative about violence toward Black men who appear to challenge their movement.

To say this is not to claim Goodman “used” race as a tool; it is to acknowledge that race is present whether one wants it there or not. Goodman’s body—his uniformed authority in a Black form—was part of what the mob read as it decided who to follow, who to threaten, who to treat as an enemy.

Accountability: A single officer’s heroism amid a system’s failure

One of the most seductive narratives after January 6 is that individual bravery can redeem institutional weakness. Goodman’s story is frequently deployed that way: a moral counterweight to the shame of the breach. But hero stories can become a kind of anesthetic. They let the public feel uplifted without confronting the harder questions: Why did the mob get inside? Why were officers outnumbered at key points? Why were warnings missed or minimized? How did political pressure shape security posture? How should consequences be assigned?

The post–January 6 landscape has been crowded with investigations and reports: congressional work, inspector general analyses, prosecutions, and civil society research. CREW, for example, has compiled material on January 6 defendants and how some described being incited by Donald Trump; one report notes Douglas Jensen—the man seen chasing Goodman in widely circulated footage—telling investigators that Trump’s call to be there helped fire people up to go to the Capitol. This kind of detail matters because it ties the stairwell drama to the larger machinery of mobilization. The mob did not appear from nowhere; it was summoned, primed, and aimed.

Goodman’s footage often focuses on a single pursuer—Jensen—because a camera makes narrative out of individuals. But the broader legal and investigative record makes clear that the force pressing into the building was collective. Good policing decisions in a corridor cannot erase the strategic failure of preventing the breach in the first place.

In that sense, Goodman’s story is both inspiring and indicting: inspiring because it shows what competence can do under pressure; indicting because it shows how much was left to improvisation.

Honors and memory: What the state chooses to reward

The United States honored Goodman in multiple ways: the Senate vote on the Congressional Gold Medal and later recognition connected to the White House’s Presidential Citizens Medal ceremony.

The Guardian reported on the Senate’s unanimous consent action and the chamber’s standing ovation, emphasizing how rare and significant the Congressional Gold Medal is as an honor. In January 2023, the Associated Press reported that President Biden planned to award the Presidential Citizens Medal to individuals involved in defending democracy on January 6, including Goodman. Official photos and wire coverage from the ceremony also place Goodman among the recipients.

Honors serve multiple purposes at once. They are gratitude. They are narrative. They are a state’s attempt to stabilize meaning after chaos. But they can also be a way of outsourcing institutional repair onto individuals: the system says “thank you” to a person, hoping the thank-you can stand in for the harder work of change.

For Goodman, honors likely came with genuine pride and also with the complicated awareness that medals do not unbreak doors, un-injure bodies, or un-radicalize a movement.

The courtroom: When “what happened” becomes evidence

If the Senate chamber is where democracy performs, the courtroom is where democracy audits. Goodman’s 2022 testimony—reported by AP and The Washington Post—matters because it anchors the stairwell sequence to prosecutable facts: the Confederate flag, the jab, the chase, the encounter’s texture.

In the courtroom, the question is not “Was he a hero?” It is: what did the defendant do; what did the witness observe; what does the law say about entering, assault, obstruction. The trial setting strips away some of the mythic framing and replaces it with accountability’s bluntness.

For the public, this shift can be disorienting. We prefer heroes who stay in the symbolic register—faces on posters, names in speeches. But the legal system requires the hero to become a witness, the story to become a sequence, and the national trauma to become a set of exhibits.

That is a different kind of burden.

A professional life after a public moment: Returning to the building

The hardest part of Goodman’s story may be the part the public cannot easily film: what it means to return, day after day, to a workplace that became a battleground; what it means to patrol corridors where a mob once surged; what it means to maintain professionalism while the country argues over whether the violence you witnessed “counts.”

In the political years after January 6, new disputes emerged over how the event should be investigated and remembered, including renewed congressional efforts to re-litigate the story. These disputes do not remain on cable news. They seep into institutional morale and public legitimacy. For Capitol Police officers, legitimacy is not a philosophical concept; it is the difference between the public accepting their authority or treating them as enemies.

At the same time, the Capitol Police as an agency has undergone leadership shifts and reforms in the post–January 6 environment, reflecting the continued pressure to adapt. The details of these reforms matter less here than the reality they imply: the institution is still living inside the aftershock.

And so is Eugene Goodman.

What Eugene Goodman’s story reveals—beyond the stairwell

There is a temptation, especially in American civic storytelling, to treat January 6 as an aberration—an unthinkable break from normalcy. But Goodman’s story suggests something more unsettling: that democracy’s defense often depends on ordinary public servants making extraordinary choices because systems do not always hold.

Goodman did not “solve” January 6. He did not stop the breach. He did not singlehandedly restore order. What he did—based on the public record and the consensus of contemporaneous reporting—is narrower and, in its way, more profound: he bought time. He redirected danger. He acted as if seconds mattered.

That is not cinematic heroism. It is professional competence under moral pressure.

It also raises questions Americans often avoid:

What does it mean that the security of elected officials came down, in part, to a lone officer’s improvisation in a corridor?

What does it mean that, years later, some political actors still attempt to shift blame or muddy the event’s meaning, even as prosecutions and investigative records continue to accumulate?

What does it mean that an officer’s most detailed public “testimony” came in a criminal trial—because the country’s legislative debate over January 6 remains contested ground?

If Goodman’s story has a throughline, it is not fame. It is duty performed inside a democracy that sometimes cannot agree on what duty is.

Coda: The landing as a national metaphor—and a warning

The landing where Goodman confronted the mob has been described so many times it risks becoming cliché. But clichés are often just truths repeated until they sound less sharp. The truth is that on January 6 the United States came close to scenes it had long associated with other places: lawmakers cornered, hostages taken, summary violence inside a seat of government. Goodman’s own reported comment that the day could have been a “bloodbath” is not rhetorical flourish; it is an assessment from someone who was there.

In that sense, Eugene Goodman is not only a symbol of bravery. He is also a reminder of fragility: that a system can be breached, that a crowd can move faster than procedure, and that democracy sometimes survives because someone in a uniform decides—without certainty, without backup—that he will become the thing the danger follows.

The republic should not need stairwell miracles.

But on January 6, it did.