KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

Two Moments, One Logic: 1989 and 2021

Lead-Up to the 2021 Inauguration: “Stop the Steal” Rhetoric Versus May 1, 1989

There is a particular kind of American sentence—half prophecy, half threat—that returns whenever power feels contested: the system is rigged; therefore, whatever we do next is self-defense. It echoed through the weeks between Election Day 2020 and January 20, 2021, as Republican officials, influencers, and rank-and-file voters repeated baseless claims of widespread fraud in a drumbeat that treated evidence as optional and certainty as a civic virtue. The narrative was elastic enough to survive court losses, recounts, audits, and public explanations by election administrators; it did not require proof, only repetition. The House January 6 committee later described a “multi-part” effort to overturn the election that relied on sustained pressure campaigns and misinformation, culminating in the attack on the Capitol.

Donald Trump’s own language on January 6, 2021, made the logic explicit: he framed the election as “fraudulent,” then told the crowd that “we love you” and “you are very special,” even as violence unfolded and the certification process was interrupted. formulation—validation first, restraint second—would become the emotional template for a movement that cast itself as wronged, and its participants as patriots rather than perpetrators.

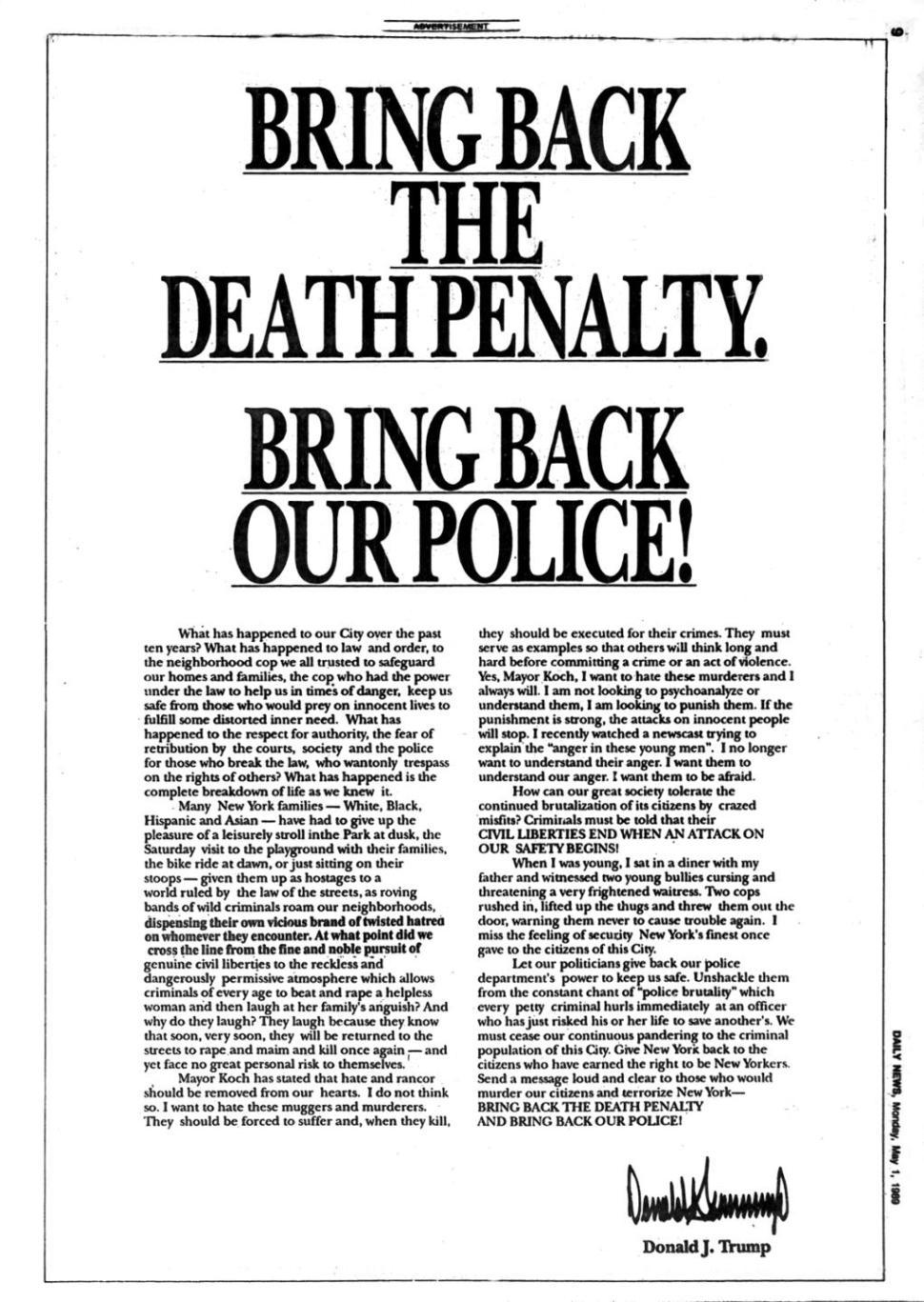

Now place that beside an earlier moment when Trump, then a New York real estate celebrity, performed a different kind of rhetorical work—less absolution than acceleration. On May 1, 1989, days after the arrests of five teenagers later known as the Central Park Five (Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Yusef Salaam, Raymond Santana, and Korey Wise), Trump purchased full-page ads in major New York papers under the headline: “BRING BACK THE DEATH PENALTY. BRING BACK OUR POLICE!” The text did not name the teenagers, but it did not need to. In the public imagination, the case had already been racialized and sensationalized; Trump’s intervention functioned as both endorsement and amplification of the harshest possible response.

The ad’s most revealing move was not the policy demand itself—many New Yorkers, frightened by crime, were open to punitive politics—but the affect. Trump wrote that he wanted to “hate” the “muggers and murderers,” urging suffering and execution as a civic lesson. It was not just an argument for punishment; it was an invitation to moral certainty in the absence of adjudicated facts.

So the comparison begins here: in 1989, Trump’s public language pressed the accelerator on vengeance against (ultimately) innocent teenagers; in 2020–21, his language pressed the accelerator on grievance, then later offered a vocabulary of solidarity to those who acted on it.

The rhetorical throughline is not simply “tough” versus “soft.” It is directional. When the targets are out-group figures—Black and Latino teens accused amid panic—Trump’s posture is maximal retribution. When the subjects are his political supporters—people who took his election claims as marching orders—Trump’s posture shifts toward vindication and rescue. The difference is not subtle; it is institutionalized in a document.

On January 20, 2025, President Trump issued a proclamation granting pardons and commutations for offenses connected to January 6, framing the prosecutions as a “grave national injustice” and describing clemency as the beginning of “national reconciliation.” The proclamation’s language is sweeping, aimed not at individualized assessments but at rewriting the moral status of an entire category of defendants.

What 1989 and 2025 share is Trump’s preference for declarative moral labeling over procedural humility. The difference is who receives the benefit of his doubt.

Parallel Timelines: Condemnation Without Proof, Forgiveness Without Accountability

A Compressed History of Trump’s Public Moral Judgments

1989–2002: Central Park Five era and after

May 1, 1989: Trump runs the full-page ad calling for the death penalty and stronger policing.

1990s: Trump periodically reiterates “law and order” themes in media appearances tied to the case’s notoriety (often through generalized claims rather than case-specific evidence). (This period is heavily mediated; the most documentable anchor remains the ad itself and later comments once the men were exonerated.)

2002: The convictions are vacated after Matias Reyes’ confession and DNA evidence; the case becomes a landmark of wrongful conviction discourse. (Trump’s later refusal to apologize makes 2002 the key factual turning point.)

2016: During the presidential campaign, Trump maintains that the men were guilty; the dispute becomes a symbol of racialized criminal-justice politics.

June 2019: As the case returns to the national conversation, Trump again refuses to apologize, asserting that the men “admitted their guilt,” despite exoneration.

September 2024: The Exonerated Five sue Trump for defamation after he repeats false claims during a debate; Trump seeks dismissal.

2020–2025: Election denial, January 6, and clemency

Nov 2020–Jan 2021: Trump and allies promote baseless fraud claims; the narrative becomes a core identity marker for many Republican voters.

Jan 6, 2021: Trump calls the election “fraudulent,” then tells rioters “we love you” and urges them to go home.

2022–2024: Trump repeatedly refers to Jan. 6 defendants as “hostages” and “patriots” in campaign rhetoric, promising pardons.

Jan 20, 2025: President Trump issues the clemency proclamation granting broad pardons and commutations for January 6-related offenses, framing it as “national reconciliation.”

Dec 18, 2025: CREW reports at least 33 pardoned January 6 defendants later faced other criminal charges; it highlights specific post-clemency incidents involving several individuals in this story.

This is the juxtaposition that matters: Trump’s Central Park Five story is a decades-long refusal to concede error after exoneration; his January 6 story is a rapid institutional act of forgiveness, backed by the machinery of presidential clemency.

Refusal and Redemption: Trump’s Selective Moral Memory

Why Apology Was Never an Option

In 2019, asked again about the Central Park Five, Trump did not retreat. He did what he often does when confronted with a factual reversal: he reasserted the original moral claim, essentially arguing that the exoneration did not compel contrition. He insisted they had “admitted their guilt,” a statement that functioned less as a legal argument than as an insistence that his early instincts were righteous. The refusal to apologize is not an incidental detail; it is the backbone of the Central Park Five chapter. If apology is an admission that one’s certainty was misdirected, Trump’s posture has been to treat certainty as the thing that must never be surrendered.

That posture intensified into the 2024 election cycle, when Trump’s statements about the men became the subject of litigation after he repeated false claims in a debate; Reuters reported on the subsequent legal maneuvering as Trump sought to dismiss the defamation suit. The case is not only about reputational harm; it is about the persistence of a story Trump appears unwilling to release—the story of five teenagers as permanent suspects.

Now compare that to how Trump has spoken about January 6 defendants: as victims of political persecution and as embodiments of a betrayed nation. The “hostages” framing is widely documented in campaign coverage, including by the Associated Press and The Guardian, and it was not merely rhetorical—it became predictive. When he returned to office, he translated the frame into governance through a proclamation that declared a “grave national injustice” and initiated “national reconciliation.”

The disparity is not just that one group is forgiven and another is not. It is that Trump’s theory of justice appears to shift depending on whether the subjects reinforce his identity politics or threaten it.

For the Exonerated Five, the state’s error is treated as irrelevant to Trump’s certainty.

For January 6 defendants, the state’s prosecution is treated as evidence of the state’s corruption.

It is a worldview in which “justice” can become a synonym for “my side wins.”

The Pardons: Scope, Signal, and Consequence

From Campaign Promise to Governing Doctrine

President Trump’s January 20, 2025 proclamation was designed as a mass action, not a case-by-case mercy. It extended pardons broadly to individuals convicted of January 6-related offenses (with a separate category of commutations for named individuals). The Department of Justice’s pardon office subsequently published guidance on certificates for those covered.

Whatever one’s politics, the operational consequence of a blanket clemency initiative is straightforward:

Immediate legal relief for covered January 6 convictions and penalties, including the removal of ongoing supervision tied to those convictions for many individuals.

A symbolic signal that reframes defendants from lawbreakers to wronged citizens—an invitation to reenter public life as vindicated.

A public-safety tradeoff: clemency is not parole. It typically carries no monitoring regime akin to supervised release. CREW’s December 2025 analysis underscores that the absence of “traditional monitoring or parole” can heighten risk when recipients later face unrelated criminal allegations.

The five individuals highlighted —Christopher Moynihan, John Andries, Brent Holdridge, Zachary Alam, and Nathan Pelham—sit inside the political argument as test cases. They are not the most famous January 6 defendants. That is precisely why they matter: they show what blanket clemency does at the street level, not the cable-news level.

CREW’s reporting identifies all five in the orbit of post–January 6 criminal justice contact, whether through new charges, convictions, or violent incidents with police. What emerges is a person-by-person accounting grounded in court reporting and official case summaries.

Five pardoned Jan. 6 rioters and the criminal cases that followed

Christopher Patrick Moynihan

From the Senate Floor to a Felony Threat Prosecution

Christopher Patrick Moynihan’s legal trajectory illustrates the sharpest collision between January 6 clemency rhetoric and post-clemency criminal accountability. Moynihan was convicted in federal court for his role in the January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol, where prosecutors established that he breached police barricades, entered restricted areas, and ultimately made his way into the U.S. Senate chamber. Court filings described him as among the earliest wave of rioters to overwhelm law enforcement lines, an aggravating factor that prosecutors emphasized during sentencing.

In 2023, a federal judge sentenced Moynihan to 21 months in prison, followed by supervised release, citing both the seriousness of the offense and the symbolic harm caused by occupying the Senate floor during the constitutional certification of the presidential election. The sentence placed Moynihan squarely within the category of January 6 defendants convicted of felony conduct tied to obstruction of an official proceeding—one of the most serious charges levied against rioters.

That conviction was nullified in legal effect—but not erased from history—when President Donald Trump issued a sweeping clemency proclamation on January 20, 2025. Moynihan was among those whose January 6 conviction was pardoned, releasing him from remaining federal penalties and supervision connected to the Capitol attack. The proclamation framed the relief as part of a broader effort to correct what Trump described as a “grave national injustice.”

Less than a year later, Moynihan again became the subject of criminal prosecution—this time in New York state court, for conduct wholly unrelated to January 6. In October 2025, prosecutors charged Moynihan with making a terroristic threat, a felony offense under New York law. According to court filings reported by CBS News, investigators alleged that Moynihan sent text messages discussing a plan to “eliminate” House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries during a public event in New York City.

Prosecutors characterized the alleged communications as credible threats rather than hyperbolic political speech, noting references to timing, location, and intent. The charges triggered Moynihan’s arrest and pretrial detention considerations, with the court weighing flight risk and danger to the community. Moynihan’s defense counsel has not publicly conceded the allegations, and the case remains pending, with motions expected to test the admissibility of the digital evidence and the intent threshold required under New York’s terroristic threat statute.

The Moynihan case has become a focal point for critics of blanket clemency. Unlike defendants whose post-January 6 conduct has been limited to rhetoric or minor offenses, Moynihan’s alleged actions—if proven—would constitute a direct threat to an elected official. The fact that the alleged threat emerged after he was publicly validated through a presidential pardon complicates claims that clemency functioned as “reconciliation.” Instead, Moynihan’s post-pardon prosecution underscores the limits of symbolic absolution when an individual’s conduct continues to implicate public safety.

John D. Andries

A Federal Felony Plea Followed by State-Level Convictions

Jan. 6 – John D. Andries entered the January 6 criminal record not through trial but through a guilty plea, a fact that differentiates his case from many others later pardoned. In 2021, Andries pleaded guilty in federal court to obstruction of an official proceeding, admitting that he knowingly participated in efforts to halt the certification of the 2020 presidential election. The plea agreement reflected acknowledgment of responsibility and spared the government a contested trial.

In 2022, a federal judge sentenced Andries to one year and one day in prison, a term that placed him above misdemeanor offenders but below defendants convicted of violent assaults. The sentence also included supervised release conditions intended to monitor post-incarceration conduct. Prosecutors emphasized that while Andries was not accused of assaulting police, his participation in the obstruction carried constitutional significance.

Like Moynihan, Andries received relief under Trump’s January 20, 2025 clemency proclamation, which wiped away federal penalties tied to January 6. The pardon terminated any remaining supervision connected to his Capitol conviction and reframed his criminal history—at least legally—as one of forgiveness rather than adjudication.

Post Jan. 6 – However, Andries soon appeared again in the criminal justice system, this time at the state level in Maryland, in a case entirely unrelated to the Capitol attack. In June 2025, a Maryland court convicted Andries of two counts of violating a peace order, following a bench trial. According to court reporting, the peace order had been issued to protect the mother of his child, and prosecutors alleged that Andries repeatedly violated its terms by contacting her and appearing at prohibited locations.

The court imposed a sentence that included jail time and probation, signaling judicial concern about compliance with court-ordered boundaries. Unlike his January 6 case—which revolved around political ideology and mass action—the peace-order violations centered on interpersonal conduct and domestic safety, areas where courts typically exercise little tolerance for repeat violations.

Andries’ case illustrates a quieter but equally significant consequence of mass clemency: the removal of federal supervision does not equate to behavioral rehabilitation. His Maryland convictions are final adjudications, not allegations, and they place Andries among those whose post-clemency conduct resulted in new criminal penalties. Critics have pointed to his case as evidence that clemency, when granted categorically, can prematurely remove oversight mechanisms that might otherwise deter or detect harmful behavior.

Brent John Holdridge

From Capitol Defendant to Commercial Burglary Allegations

Jan. 6 – Brent John Holdridge’s January 6 case placed him within the broad cohort of defendants charged for unlawful entry and related offenses stemming from the Capitol breach. While his role was not among the most violent or high-profile, he nevertheless faced federal prosecution and potential incarceration before receiving relief under President Trump’s 2025 clemency proclamation.

Public court records indicate that Holdridge’s January 6 charges were resolved prior to the pardon, though they did not result in a lengthy prison sentence. His inclusion in the clemency action eliminated any remaining federal exposure related to the Capitol attack and restored his legal status with respect to those offenses.

Post Jan. 6 – In May 2025, Holdridge was arrested in Humboldt County, California, on commercial burglary and grand theft charges, according to local law enforcement reports. Authorities alleged that Holdridge participated in the theft of large quantities of industrial copper wire from a commercial facility, a crime that carries significant penalties due to the high value of stolen materials and the disruption caused to infrastructure.

Sheriff’s office statements described the alleged burglary as involving tens of thousands of dollars in losses, and prosecutors filed charges including burglary, possession of stolen property, and theft of utility infrastructure. At the time of reporting, Holdridge entered a not-guilty plea, and the case remains pending, with preliminary hearings focused on evidence linking him to the scene and the valuation of stolen materials.

Unlike other post-clemency cases involving threats or violence, Holdridge’s alleged conduct falls within the realm of property crime. Nonetheless, the case has been cited by ethics watchdogs as part of a broader pattern: individuals whose January 6 convictions were erased through clemency later reappearing in criminal court without the deterrent effect of federal supervision.

If convicted, Holdridge could face state prison time, restitution orders, and probation. The outcome will likely hinge on forensic evidence, surveillance footage, and the prosecution’s ability to establish intent and participation. Regardless of adjudication, the case reinforces the central policy critique of blanket pardons—that they substitute political symbolism for individualized risk assessment.

Zachary Alam

Violent Capitol Conduct, an Eight-Year Sentence, and a Post-Pardon Arrest

Jan. 6 – Zachary Alam was among the most aggressively prosecuted January 6 defendants due to his highly visible and violent conduct. Federal prosecutors proved that Alam smashed the glass panel in the Speaker’s Lobby door—a breach that occurred moments before Ashli Babbitt was fatally shot while attempting to enter the restricted area.

In 2023, a federal judge sentenced Alam to eight years in prison, one of the longest sentences imposed on any January 6 defendant. The court cited the danger posed by his actions, the proximity to lethal force, and his lack of remorse as aggravating factors. The sentence included supervised release and restitution.

That sentence was effectively nullified by Trump’s 2025 clemency proclamation, which pardoned Alam’s January 6 convictions and resulted in his release. The decision drew sharp criticism from prosecutors and victim-impact advocates who viewed Alam’s conduct as emblematic of the riot’s most dangerous moments.

Post Jan. 6 – In May 2025, Alam was arrested in Henrico County, Virginia, and charged with breaking and entering and larceny following an alleged residential burglary. Local prosecutors allege that Alam unlawfully entered a home and stole personal property. He was taken into custody and later released pending trial.

As of this writing, Alam’s Virginia case remains pending, with defense counsel disputing aspects of the identification and intent elements of the charges. If convicted, Alam faces potential state incarceration, separate from any federal consequences erased by the pardon.

Alam’s post-clemency arrest has become one of the most frequently cited examples in debates over Trump’s pardons. His case underscores the tension between Trump’s portrayal of January 6 defendants as victims and the factual record of violent conduct followed by new criminal allegations.

Nathan Donald Pelham

Capitol Charges and a Violent Arrest Involving Gunfire

Pre Jan. 6 – Nathan Donald Pelham’s legal history predates Trump’s 2025 clemency action and raises distinct concerns due to allegations of gunfire directed at law enforcement. Pelham was charged in connection with January 6, though his case did not reach the sentencing phase before subsequent events overtook it.

Post Jan. 6 – In April 2023, law enforcement officers attempting to arrest Pelham in Texas encountered armed resistance. According to court records and contemporaneous reporting, Pelham allegedly fired shots toward officers during the attempted arrest. He was taken into custody after a standoff and charged with aggravated assault on a peace officer, among other offenses.

Those charges are state-level and unrelated to January 6, but they significantly altered the context of Pelham’s political narrative. Unlike other defendants whose post-January 6 conduct involved speech or property crimes, Pelham’s alleged actions implicated direct physical danger to police officers.

The Texas case has proceeded through pretrial motions, with defense attorneys challenging aspects of the arrest and use-of-force evidence. As of late 2025, portions of the case remain pending, while other charges have advanced toward trial or plea negotiations.

Pelham was included in President Trump’s January 6 clemency action, which removed any remaining federal exposure tied to the Capitol attack but had no effect on his Texas charges. Ethics watchdogs have nevertheless cited Pelham’s inclusion as emblematic of the risks of mass pardons that do not distinguish between nonviolent offenders and those with histories of armed confrontation.

If convicted in Texas, Pelham faces significant prison time, potentially exceeding what he would have served for January 6 offenses alone. His case stands as the starkest example among the five of how clemency can intersect with ongoing patterns of dangerous behavior rather than marking an endpoint.

Lives Reclaimed: The Exonerated Central Park Five

What Innocence Looks Like After the State Is Finished With You

If the January 6 clemency story asks what the state owes the guilty—or the politically aligned—the Central Park Five story asks what the state owes the innocent after it has taken years of their lives. The five men have spent decades building lives that are, in different ways, acts of repair: family life, advocacy, public service, and sustained public testimony about how wrongful convictions happen.

Trump has remained, stubbornly, an antagonist in that repair. Even after exoneration, he refused to apologize and continued to claim the men “admitted their guilt.” That refusal has functioned as a recurring injury—less about a single politician’s opinion than about the social permission structure that his opinion confers.

Below are brief portraits of the Exonerated Five—deliberately grounded in their voices.

Antron McMray

Private Rebuilding as an Achievement in Itself

Antron McCray’s post-exoneration life is often described in the language of quietness—work, family, distance from New York’s glare—but that quiet is not absence. It is an accomplishment. McCray’s public identity was formed through accusation, coerced confession dynamics, and incarceration; the life he built afterward has been shaped by a deliberate refusal to remain permanently assigned to that script. He moved away from New York and established stability in the South, working ordinary jobs and raising a large family—precisely the ordinary future that the case attempted to foreclose. Reporting and case profiles note that McCray has worked as a forklift operator and has built family life after release.

McCray’s most consistent public “work,” when he chooses to speak, is not branding or electoral politics—it is testimony about what wrongful conviction does to intimacy and trust. He has been candid about the particular wound of the case: his father’s role in urging him to cooperate with police under the belief it would allow him to go home. In accounts tied to the renewed attention around When They See Us, McCray has described the damage in terms that do not translate easily into triumphant narrative. He has spoken about the emotional contradictions of family loyalty under duress, and how the harm persists in the most personal spaces—parenthood, memory, and forgiveness.

What McCray has accomplished, then, is a form of reintegration that rarely receives headline treatment: staying employed, raising children, and refusing to let a single coerced narrative define his moral identity. The Innocence Project, in an essay focused on fatherhood among exonerees, underscores that McCray is a father of six and highlights a quote that captures both his insistence on honesty and his awareness of how the system weaponized “confession” against him. “I preach to my kids, ‘Just tell the truth. Be true to who you are,’” McCray said. “Honestly, the last time I lied, got me 7.5 years for something I didn’t do.”

That sentence is not only a parental maxim; it is a critique of how the justice system can invert the moral meaning of truth. In McCray’s telling, what the state called an admission was not truth but survival. His accomplishment is that he has turned that hard lesson into a concrete ethic for the next generation—one that insists on self-definition, even when institutions attempt to impose a counterfeit identity.

Kevin Richardson

Civic Education as Reparative Leadership

Kevin Richardson’s post-exoneration accomplishments are notable not only for their visibility but for their specificity: he has built a public platform around the practical mechanics of civil rights—how to survive police encounters, how to keep fear from becoming confession, how to understand the state’s power in real time. Richardson, who was the youngest of the five when arrested, has used his biography as a curriculum, often speaking at universities and civic events about false confessions, youth vulnerability, and the procedural failures that make wrongful convictions possible.

Richardson’s most concrete recent initiative is his youth-facing workshop, C.P.R. (Courage, Perseverance and Resilience). The program is designed to educate teenagers—particularly young people of color—about navigating police encounters and understanding their civil rights. In a 2025 CBS News New York segment on the workshop, Richardson described the central rationale with a clarity that reflects the brutal pragmatism of someone who learned civil procedure from the inside: “It’s very important for people to know how to navigate through that and know your rights, because it is your civil rights,” he said.

This kind of work is an accomplishment precisely because it is not abstract advocacy. It translates the story of wrongful conviction into usable knowledge for people who are still vulnerable to the same pressures he faced at 14. Additional coverage has framed the workshop as addressing over-policing, mass incarceration, and the shrinking zone of civil liberties that many young people experience not as theory but as routine contact with authority.

Richardson has also participated in public commemorations and institutional memory projects that reposition the Exonerated Five not as tabloid figures but as civic witnesses. The New York Public Library’s documentation of “Gate of the Exonerated” includes Richardson reflecting on public recognition and the long arc of vindication. That sort of work—public history as counter-propaganda—matters in a case where reputational harm was part of the punishment.

The accomplishment, ultimately, is Richardson’s transformation of trauma into a public service model. Where Trump’s rhetoric treated the boys as evidence of social decay, Richardson has used his adulthood to produce something closer to social infrastructure: teaching, mentoring, and equipping young people with tools the system never gave him.

Yusef Salaam

Authorship, Honors, and Electoral Legitimacy After Exoneration

Yusef Salaam has built the most institutionally visible post-exoneration portfolio among the five—publishing, public speaking, formal recognition, and elected office—yet the deeper achievement is conceptual: he has insisted on living as a person whose legitimacy is not contingent on the state’s permission. Salaam has authored a memoir, Better, Not Bitter, and his official biography also lists him as a co-author of Punching the Air. He has received major honors, including an honorary doctorate (2014) and a lifetime achievement award presented by President Barack Obama (2016), according to his NYC Council biography.

Those achievements matter in this article because they directly contradict the underlying premise of Trump’s 1989 intervention: that the boys were not just guilty, but disposable. Salaam’s career—especially his movement into public life—operates as a form of rebuttal. In 2023, Salaam won election to the New York City Council, a result that places him in the very civic machinery that failed him as a teenager. His political role is not merely symbolic; it is a public demonstration that a wrongful conviction can be followed by democratic legitimacy.

Salaam’s quotes often revolve around purpose and the irretrievability of time—language that refuses both victimhood and erasure. In a 2021 NPR interview about his memoir and the aftermath of exoneration, Salaam offered a line that functions as both summary and indictment: “When the truth came out, that’s when we got our lives back,” he said—then added the cost: “we had done all of someone else’s time.” That phrasing is crucial for this article’s moral architecture. It marks the distance between legal exoneration and existential repair.

Salaam also speaks, consistently, about resisting false narratives—an insistence that directly parallels this article’s broader argument about Trump’s disregard for facts. In a 2025 keynote address report, Salaam urged audiences to refuse participation in the creation of false narratives about others and to hold onto human dignity even when institutions attempt to strip it away.

His accomplishments—authorship, honors, elected office—are not a sentimental arc. They are evidence that the people Trump positioned as enemies of public safety have become builders of public life.

Raymond Santana

Entrepreneurship, Public Testimony, and Cultural Production

Raymond Santana’s post-exoneration life shows how “accomplishment” can mean reclaiming a suspended self. One of the case’s less discussed violences was the theft of adolescence as a time for imagination and future-building. Santana has responded to that theft by turning toward entrepreneurship and cultural production, building a brand that is both personal and civic: a fashion line rooted in neighborhood memory and the idea that identity can be authored rather than assigned.

The Innocence Project profiled Santana’s launch of Park Madison NYC, describing it as a tribute brand shaped by the geography and cultural energy of Harlem—an attempt to name the world he came from rather than remain trapped inside the name the media imposed on him. Other coverage similarly describes Santana as running a clothing business and using his platform to speak publicly about justice reform. While the marketing materials for the brand are not independent journalism, the existence of the enterprise—and Santana’s role in it—has been corroborated across advocacy and media sources.

Santana’s public-facing accomplishments also include extensive speaking and advocacy. He has framed the criminal legal system as an extractive institution that treats young Black and brown people as “commodities,” a term he used in a recorded campus talk while urging students to understand how budgets, incentives, and policing practices can collide into wrongful convictions. “The criminal system of injustice has had a long history of locking our people up and using them based on budgets and numbers,” Santana said. “You are the commodity.”

This is not only rhetoric; it is analysis derived from lived experience, offered in venues that treat him as an expert witness rather than an object lesson. At the University of the Pacific, a campus report quoted Santana describing the Exonerated Five as examples of resilience and victory against an unjust system: “We are true examples of overcoming obstacles and not giving up,” Santana said.

Santana’s accomplishments are therefore dual: he has built a livelihood that asserts creative agency, and he has built a public voice that insists the state’s narrative is not the final story. In the context of this article—where Trump uses language to assign permanent guilt—Santana’s work functions as counter-language: identity reclaimed through enterprise, and truth sustained through testimony.

Korey Wise

Philanthropic Institutional Impact and the Moral Authority of Return

Korey Wise’s post-exoneration accomplishments are among the most structurally significant because they are not only personal—they are institutional. Wise spent the longest time incarcerated and was tried as an adult, a reality that shaped both the severity of his trauma and the intensity of his later public purpose. Unlike triumphal “redemption” storytelling, Wise’s public remarks often underscore how difficult freedom can be after long confinement. In a 2010 Innocence Project event recap, Wise described reentry in childlike terms: “I’m so used to be behind the walls. I feel like a baby all over again. I’m crawling.” That quote captures a dimension of accomplishment often ignored: relearning life itself.

Wise has also authored direct advocacy, publishing a 2009 piece through the Innocence Project calling for criminal justice reform in New York and explicitly grounding his arguments in the fact of wrongful conviction and DNA exoneration. The accomplishment here is not the byline; it is the act of returning to the public sphere to argue for systemic repair, rather than retreating permanently into private survival.

Most notably, Wise has translated settlement proceeds and public recognition into philanthropic infrastructure for other wrongly convicted people. In 2015, Wise made a significant gift—widely reported as $190,000—to the University of Colorado Law School’s innocence work, enabling the program to hire a full-time director and expand investigative capacity. The University of Colorado Law School reported that Wise’s gift funded staffing and investigative support, and the program was later renamed in his honor. The Colorado Sun reported additional operational outcomes, including capacity-building tools for student investigators. Today, the Korey Wise Innocence Project describes its mission as providing investigative and legal services to people in Colorado prisons who claim wrongful conviction and mentoring students in advocacy work—an enduring institutional imprint of Wise’s decision to “give back” in a way that creates more exonerations.

Wise’s accomplishments, then, are unusually measurable: he did not only survive; he helped build a mechanism that assists others still trapped inside the system that once trapped him. In the architecture of your article—contrasting Trump’s refusal to acknowledge innocence with the men’s post-exoneration lives—Wise stands as the clearest rebuttal. He took what was extracted from him and converted it into an instrument that returns people to sunlight.

Implied Black Guilt, Presumed White Innocence

The throughline binding the Central Park Five and the January 6 rioters is not simply Donald Trump’s personal inconsistency. It is the durability of an American ethos—longstanding, adaptive, and politically useful—in which Black guilt is implied and permanent, while white innocence is presumed, elastic, and redeemable.

This ethos did not originate with Donald Trump, but he has articulated it with unusual clarity and force, and Republican voters have repeatedly rewarded him for doing so. It is an ethos that allows Trump and his political coalition to claim allegiance to “law and order” while simultaneously emptying those words of universal meaning.

Under this framework, justice is not a neutral principle but a conditional privilege.

The Central Park Five were children when Trump demanded death and suffering. When DNA evidence, a confession, and prosecutorial review proved their innocence beyond reasonable dispute, Trump did not recalibrate. He hardened. Their Blackness—amplified by the panic of the era—rendered guilt ineradicable. Exoneration, in this logic, was not proof of innocence but a technicality, a failure of the system to impose the punishment believed to be deserved.

January 6 shattered the other side of the equation.

The rioters who stormed the Capitol—overwhelmingly white, many openly aligned with Trump—were granted a presumption of innocence so expansive it could absorb video evidence, sworn testimony, jury verdicts, and guilty pleas. Trump called them peaceful. He called them patriots. He called them hostages. Republican voters echoed the language, not because the facts supported it, but because the actors fit the profile of people for whom innocence is assumed even after violence.

This is the quiet sleight of hand at the heart of selective justice: behavior matters less than belonging.

Black teenagers are presumed dangerous even when innocent.

White political loyalists are presumed virtuous even when violent.

Republican voters who champion “justice,” “due process,” and “constitutional order” only when those principles defend their own are not abandoning those ideals—they are instrumentalizing them. Justice becomes something to invoke against enemies and suspend for allies. Innocence becomes something to grant preemptively to those who reflect the party’s cultural self-image.

Trump’s mass pardons did not merely free individuals; they ratified this worldview. They declared that violence in service of his cause was not only forgivable but mischaracterized from the start. At the same time, Trump’s refusal—spanning decades—to apologize to the exonerated Central Park Five affirmed the opposite principle: that some people, once accused, are never fully innocent, no matter the evidence.

This is not hypocrisy in the casual sense. It is coherence.

An ethos of implied Black guilt and white innocence has always required selective outrage, selective memory, and selective mercy to function. Trump did not invent it. He gave it a voice, a platform, and eventually, the force of presidential authority. Republican voters did not misunderstand him. They recognized themselves in the logic and endorsed it at the ballot box.

The cost is not abstract. It is measured in stolen years, credible threats, emboldened violence, and a justice system bent by identity rather than evidence. A democracy cannot survive indefinitely under such conditions—not because disagreement is fatal, but because justice that only applies to some is not justice at all.

And the most dangerous illusion Trump and his supporters continue to sell is this: that they are defending the rule of law, when in fact they are rewriting it—one group declared guilty forever, another innocent no matter what.

This article draws on contemporaneous reporting and archival analysis from The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Guardian, Reuters, TIME, the Associated Press, and other national and local news organizations, as well as court records, sentencing memoranda, public filings, and official statements from the White House and the U.S. Department of Justice. Additional context and analysis are informed by reporting from Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW), advocacy organizations focused on wrongful convictions, and publicly available interviews, speeches, and first-person accounts from the individuals discussed.