KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

Prologue: The moment a crowd decides it will not lose

There are few scenes more American than a crowd insisting it is the real public. Sometimes that crowd is a line of voters, practicing the mundane miracle of pluralism—neighbors taking turns at the same civic instrument. Sometimes it is a mob claiming the nation has been stolen, that the ordinary rules no longer bind them, that force is a form of civic correction.

On January 6, 2021, a mob attacked the U.S. Capitol as Congress met to certify the results of the 2020 presidential election. The House Select Committee later documented the attack as part of a broader effort to disrupt the peaceful transfer of power. Accountability work and litigation tracking by Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW) has underscored that January 6 was not solely a day of violence but a long stress test of institutions: courts, legislatures, political parties, and public memory.

The modern temptation is to treat January 6 as aberration—an outburst enabled by contemporary media ecosystems and partisan radicalization. But the United States does not lack precedent for political violence aimed at reversing democratic outcomes. It lacks a consistent willingness to name such violence accurately, early enough, and with consequences commensurate to its purpose.

To see the deeper pattern, you begin not at the Capitol, but in a port city on the North Carolina coast, where an election’s aftermath became a blueprint.

In Wilmington in 1898, white supremacists overthrew a duly elected, multiracial local government through a coordinated campaign of propaganda, intimidation, and armed force—an episode long mislabeled a “riot” and now more widely described as massacre and coup. PBS has framed the event as the only successful coup d’état in U.S. history, emphasizing its intentional overthrow of lawful government.

This story is about Wilmington—what led to it, what it destroyed, and what it taught. It is also about the republic’s recurring vulnerability: the moment a faction decides it must not lose, and begins building a moral and procedural universe in which violence can be described as restoration.

Wilmington before the coup: A city where multiracial democracy briefly worked—and therefore had to be destroyed

Wilmington is not only a tragedy. It is a method.

In 1898, Wilmington was North Carolina’s largest city: a commercially significant port with social dynamism, a growing economy, and political competition that mattered statewide. It was also majority-Black, with Black Wilmingtonians building the institutions that make a city feel owned by its residents rather than merely inhabited: churches and schools, mutual aid societies and fraternal organizations, businesses and professional networks, and—most dangerously for white supremacists—visible civic authority.

Wilmington’s biracial political power rested on Fusion politics: alliances between Republicans and Populists that could win elections and govern, often with substantial Black support. Fusion was not a utopian project. It was pragmatic, negotiated, and imperfect—like most coalitions. But it produced something that white supremacist Democrats found intolerable: proof that interracial political cooperation could operate a Southern city, and that Black citizens could participate as full civic actors rather than as a permanent underclass.

That proof created an existential threat—not to “order,” as the era’s rhetoric claimed, but to a racial hierarchy that depended on Black political power remaining either absent or purely symbolic. The threat was democracy becoming durable in the hands of people who had been told, for generations, that democracy was not meant for them.

Wilmington also had a Black press. Alexander Manly’s Daily Record did not merely report news; it contested the stories used to rationalize white rule. The paper represented something white supremacist movements have always feared: a local institution capable of documenting reality from the inside.

This context is essential because it clarifies the coup’s purpose. Wilmington was not targeted because it was chaotic; it was targeted because it was functioning—because it showed what a multiracial electorate could do if left to govern itself.

The Atlantic’s framing is direct: Wilmington is a lost history of an American coup d’état, foundational to the construction of a white-supremacist state in North Carolina.

The white supremacy campaign: How propaganda becomes infrastructure, and language becomes permission

When a working democracy becomes the threat, violence can present itself as public service.

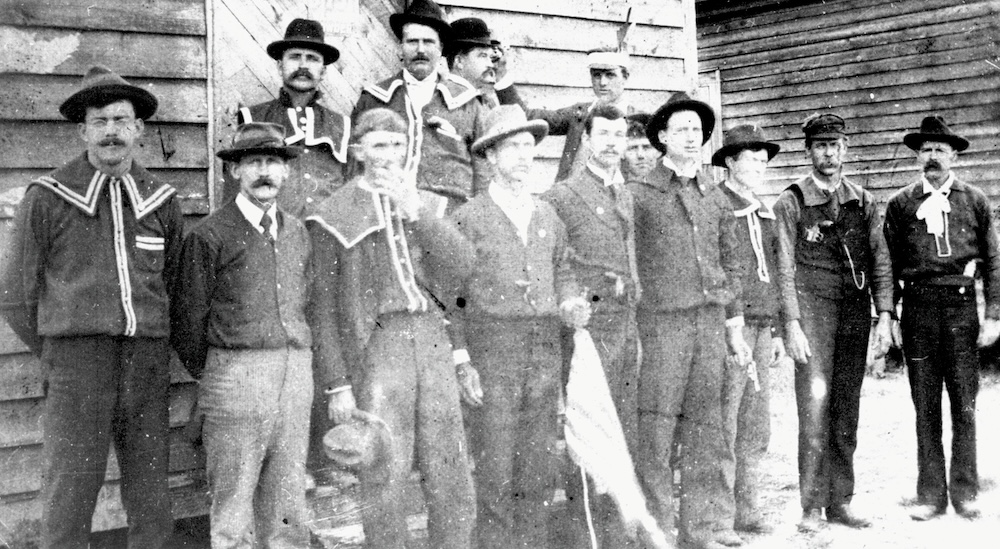

The coup did not begin with gunfire. It began with a campaign—designed, iterated, and executed with the planning of electoral strategy, except that its tools included intimidation and the credible threat of mass violence.

A timeline compiled by New Hanover County records that in 1897 North Carolina’s Democratic Party chose to pursue a “white supremacy campaign” aimed at driving Populist and Republican officials from office in 1898, using speeches, propaganda cartoons, and threats of violence to build support. The detail matters because it dissolves the myth of spontaneity. The atmosphere of menace was not incidental. It was built.

The campaign also did not emerge from nowhere. It grew from a longer rhetorical lineage that trained voters to hear interracial coalition as illegitimate—dirty by definition, contemptible in its very parentage.

In 1876, gubernatorial candidate Zebulon B. Vance described the Republican Party as “begotten by a scalawag out of a mulatto and born in an outhouse.” The insult is crude because its function is surgical: it depicts coalition politics as racial contamination and moral filth. It does not merely argue that opponents are wrong; it argues they are unfit to govern by virtue of origin. This is how democracy is delegitimized before ballots are even cast: you teach the public to experience certain coalitions as an affront to the natural order.

By the 1890s, the white supremacy campaign added a further accelerant common across the South: racial-sexual mythology. In this narrative, Black men are cast as predatory, white women as perpetually imperiled, and white violence as protective rather than criminal. Panic becomes permission.

Into this climate stepped Alexander Manly, editor of Wilmington’s Daily Record. Manly published an editorial rejecting the mythology used to justify lynching and the policing of Black life; white supremacists seized on the piece as pretext—an emblem they could amplify to intensify outrage and frame the coming violence as reluctant necessity.

Pretext is not cause. The editorial did not create the coup; it was used to rationalize one. This is a recurring feature of insurrectionary politics: manufacture or magnify an insult, inflate it into an existential crisis, and insist that “order” demands extraordinary action.

In Wilmington, propaganda served two strategic ends at once:

It criminalized multiracial governance by portraying Fusion leadership as civic collapse; and

It sanctified coercion by framing white supremacist action as rescue.

By Election Day, the city was not merely polarized; it was coached—trained to interpret violence, should it come, as restoration.

The choreography of overthrow: Election Day intimidation, the burning of the Record, and the seizure of government

When propaganda succeeds, the public begins to confuse coercion with protection.

“Riot” implies spontaneity, chaos without plan. Wilmington was a sequence.

Step one: Constrain the electorate.

On November 8, 1898, intimidation shaped Election Day. The New Hanover County timeline describes threats and coercion intended to prevent African Americans from voting and allegations of election manipulation. Voter intimidation is not merely about numbers; it is about signaling who controls the civic space. When intimidation becomes visible, participation becomes conditional—available only to those willing to pay a cost.

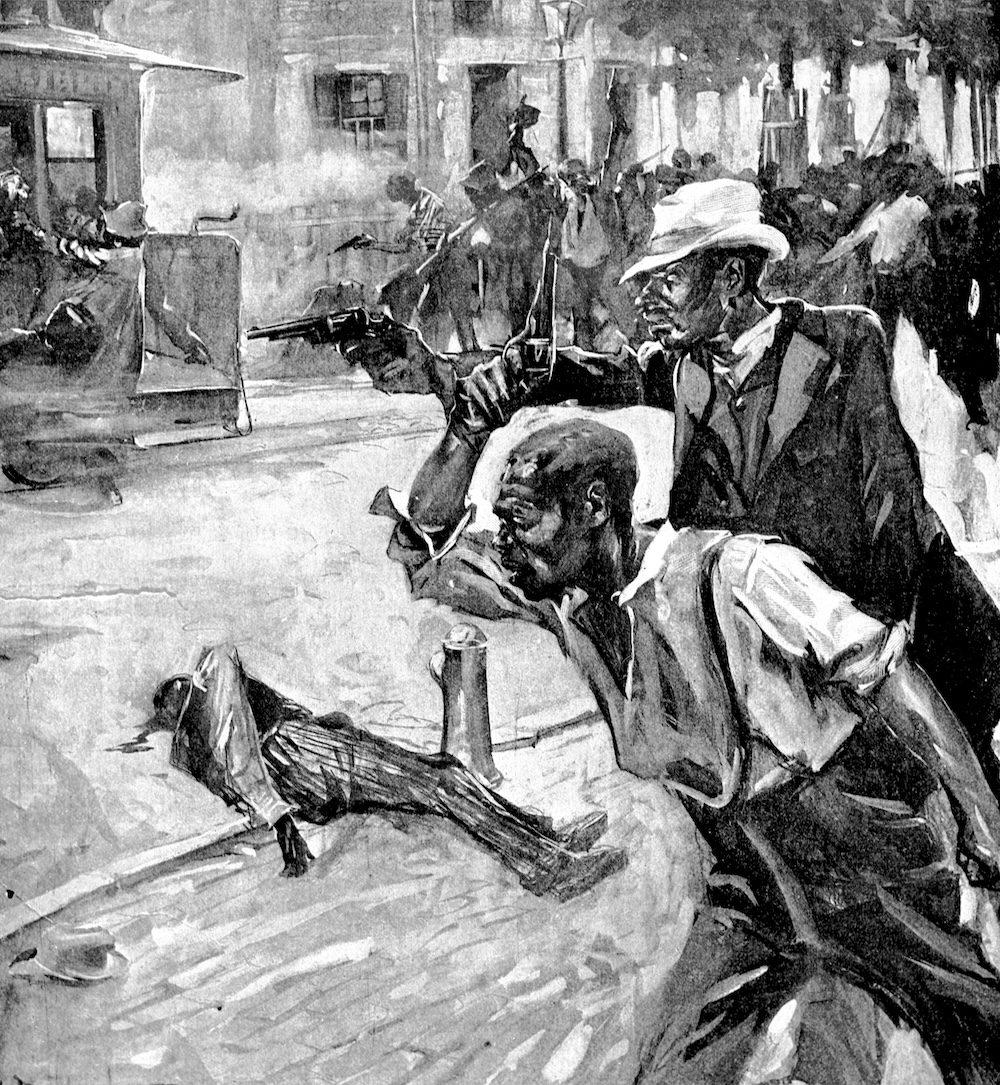

Step two: Strike the infrastructure of counter-narrative.

On November 10—two days after the election—white supremacists moved openly. Armed men targeted the Daily Record and destroyed it. Public history accounts and timelines treat the burning of the paper as a central act of the day.

Destroying a newspaper is strategic violence. It eliminates documentation, narrows the channels of truth, and warns dissenters that speech itself is punishable. In a coup, controlling the story is not a secondary objective; it is part of the takeover.

Step three: Apply force to the city’s social fabric.

After the arson, violence spread through Wilmington. Armed white men moved through Black neighborhoods, killing residents and driving people from their homes. Estimates of the number killed vary; the uncertainty is itself a legacy of terror and suppression, with later official state work cited in public history framing fatalities as potentially reaching as high as dozens.

Step four: Seize government and formalize the takeover.

The defining act of Wilmington is governmental overthrow. PBS frames the episode as an overthrow of a duly elected government—an event once mislabeled a “riot” and now more widely recognized as massacre and coup. Public accounts also describe the forced removal of officials and the installation of coup leaders, a direct replacement of lawful authority by coercion.

Thousands of Black residents fled or were driven out. Displacement is how coups become durable: by forcing people out, the new regime reshapes the electorate, the economy, and the city’s political future.

The coup’s success depended not only on weapons but on institutional collapse—local structures unwilling or unable to stop the mob, and a broader political environment ready to accept the new order. In the aftermath, the project of Black disenfranchisement accelerated across North Carolina, translating street violence into law and policy.

A coup’s afterlife: How Wilmington became a template—through impunity and euphemism

The street becomes the legislature when intimidation is allowed to stand in for legitimacy.

A successful coup does not end when the shooting stops. It persists in the form of method, memory, and the quiet lessons transmitted to future actors.

Wilmington taught four lessons that recur throughout American history when democracy is treated as conditional.

Lesson 1: Violence can be made to look like governance

For decades, Wilmington was popularly mislabeled a “race riot,” language that blurs intent and diffuses culpability. Public history emphasizes how understanding has shifted over time: what was once framed as riot is now more widely understood as massacre and overthrow.

This is not semantic trivia. Naming determines consequence. If it was a “riot,” then perhaps it was inevitable, mutual, ungovernable. If it was a coup, then the failure to punish becomes itself a political fact—one that invites repetition.

Lesson 2: Control the story, and you control the republic’s memory

The burning of the Daily Record is Wilmington’s narrative signature. It demonstrates that insurrectionary politics does not only target buildings and officials; it targets the channels through which a community can tell the truth about itself.

Lesson 3: Impunity is instruction

Public accounts emphasize that perpetrators faced limited accountability and that coup leaders gained power. Impunity turns violence into tutorial. It teaches future movements that coercion can be absorbed into normal governance—especially when justified as “order.”

Lesson 4: The real target was coalition

Wilmington was an attack on Black citizens, but also on the possibility of interracial governance. Fusion politics demonstrated that durable majorities could be assembled across race and class lines. The coup made coalition-building dangerous and therefore narrowed democracy’s plausible future.

From Wilmington’s blueprint to a national pattern: “Restoration” as recurring political technology

A coup becomes precedent when the nation allows it to be misremembered

If Wilmington is the case study, the 20th century is the distribution phase. The details vary, but the mechanics—propaganda, intimidation, force, laundering—reappear at moments when equality threatens to become durable.

Wilmington’s core move was to portray democratic inclusion as civic emergency. Once inclusion is an emergency, coercion can be pitched as rescue. This logic migrates well because it is adaptable: the “threat” can be Black officeholding, labor organizing, federal authority, or electoral defeat. The underlying claim is constant: the outcome is illegitimate, and extraordinary action is therefore justified.

Wilmington also demonstrates the importance of the preparatory phase. When the public is conditioned to expect danger, violence appears less like crime and more like inevitability. That conditioning can take the form of cartoons and speeches in 1898. It can take the form of mass media and algorithmic amplification in the 21st century. But the operational function is the same: build the interpretive environment in which coercion seems normal.

The coercive repertoire in the early 20th century: Racial terror as political enforcement

In the early 20th century, mass racial violence surged across U.S. cities and towns. These episodes were often triggered by labor conflicts, rumors, accusations, or competition—but the deeper purpose frequently aligned with Wilmington: to police the boundaries of Black citizenship and to punish Black advancement.

The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 remains among the most notorious examples—an assault that destroyed the Greenwood district, a prosperous Black community. Tulsa did not replicate Wilmington’s municipal overthrow, but it replicated Wilmington’s functional aim: demonstrate that Black prosperity and autonomy were fragile in the face of organized white violence, and that institutions could fail or participate when racial hierarchy felt threatened.

And then comes the afterlife question: what does the nation do with the violence? Reparations, prosecutions, institutional reforms—or avoidance and euphemism. When the afterlife is avoidance, the method remains available.

Mid-century backlash: When democratic expansion triggered organized counter-mobilization

The mid-20th century contains both the moral clarity of civil rights victories and the darker continuity of backlash. As democratic inclusion expanded, counterforces mobilized—sometimes openly violent, sometimes institutionally strategic, often both.

This is where Wilmington’s method appears in a more “respectable” guise. Explicit slogans can be replaced by constitutional euphemisms—“states’ rights,” “local control,” “law and order”—that sound principled while functioning as defenses of hierarchy. The laundering begins before the conflict even arrives.

Intimidation also becomes more institutionally entangled. It is not only the mob; it is the threat of losing a job, the denial of credit, the harassment of organizers, the strategic use of policing to narrow civic space. Intimidation does not need to succeed everywhere. It needs only to succeed enough that participation becomes uneven.

The method persists: delegitimize reform as disorder, pressure participation, and insist that coercion is protection. Wilmington is not repeated verbatim, but it is echoed in structure.

Late-20th-century grievance politics: Delegitimization as culture, coercion as option

By the late 20th century, a strand of American political violence increasingly presented itself as anti-government, anti-federal, conspiratorial—less explicitly tied to Jim Crow rhetoric, but still rooted in the delegitimization of institutions. This is where the throughline shifts from race-explicit propaganda to legitimacy-crisis politics: the sense that the system is captured, the government counterfeit, the opposition treasonous.

The connective tissue to Wilmington is method, not ideology. Wilmington teaches that violence becomes thinkable when a faction decides the system is illegitimate and that defeat must be reversed outside normal procedure. Delegitimization is the psychological bridge from grievance to action.

Modern media accelerates this bridge. In 1898, propaganda moved at the speed of print and speech. In the contemporary era, propaganda can be constant, personalized, and amplified at scale. The cycle tightens: moral emergencies can be manufactured daily, and a population can be habituated to the idea that compromise is betrayal and defeat is theft.

January 6, 2021: A modern insurrection built from familiar materials

Washington on January 6 is not Wilmington in 1898. But the rhyme is operational: delegitimize an outcome, mobilize grievance, target a decisive political procedure, then contest the meaning afterward.

On January 6, 2021, a mob attacked the U.S. Capitol during Congress’s certification of the election results, disrupting the process. The House Select Committee later documented the attack within a broader effort to block the transfer of power, and its materials and summary are archived through official channels. CREW’s work tracks accountability and related litigation and argues that the institutional response is part of democratic self-defense.

Mapped against Wilmington’s modules:

Propaganda: defeat is reframed as illegitimacy (“stolen election” rather than loss).

Intimidation: institutional actors are pressured—by presence, threats, disruption—to treat lawful procedure as negotiable.

Force: a decisive political moment is physically attacked to stop or delay outcome.

Narrative laundering: language becomes the first battlefield—riot vs. insurrection, protest vs. coup—because naming governs consequence.

Wilmington’s Daily Record burned as a strike against Black testimony and civic legitimacy. January 6 targeted the mechanism that converts votes into authority. Different symbols, similar aim: to break the chain between democratic choice and lawful governance.

Coda: Wilmington’s question for the present—will the country name the method in time?

Wilmington demonstrates that American democracy has been vulnerable not only to violence, but to euphemism. A coup mislabeled becomes precedent disguised as accident. A massacre framed as “unrest” becomes tragedy without perpetrators.

Zebulon B. Vance’s 1876 slur—“begotten by a scalawag out of a mulatto and born in an outhouse”—belongs in this story because it shows how the ground is prepared long before violence. When a public is taught to experience multiracial coalition as contamination, coercion can be framed as cleansing. When coalition is made to sound illegitimate by definition, overthrow can be made to sound like sanitation.

Wilmington operationalized that logic: propaganda as permission, intimidation as narrowing, force as replacement, laundering as durability. January 6 tested a modern version of the same vulnerability: whether a democratic defeat can be rebranded as theft, and whether a mob can be reframed as the people.

The republic’s most vulnerable hours are rarely the hours when violence is already underway. They are the hours when propaganda is turning civic opponents into existential enemies, when intimidation is being normalized, and when the public is being coached—subtly, steadily—to accept coercion as “order.”

Wilmington teaches what happens when that coaching succeeds.

The question the United States must answer—again and again, from 1898 to 2021 and beyond—is not whether insurrection can happen here. It has. The question is whether the country will recognize the method early enough, name it honestly enough, and respond with consequences firm enough that a faction learns what Wilmington’s perpetrators did not have to learn: that democracy is not merely a system of rules, but a system worth defending.