KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

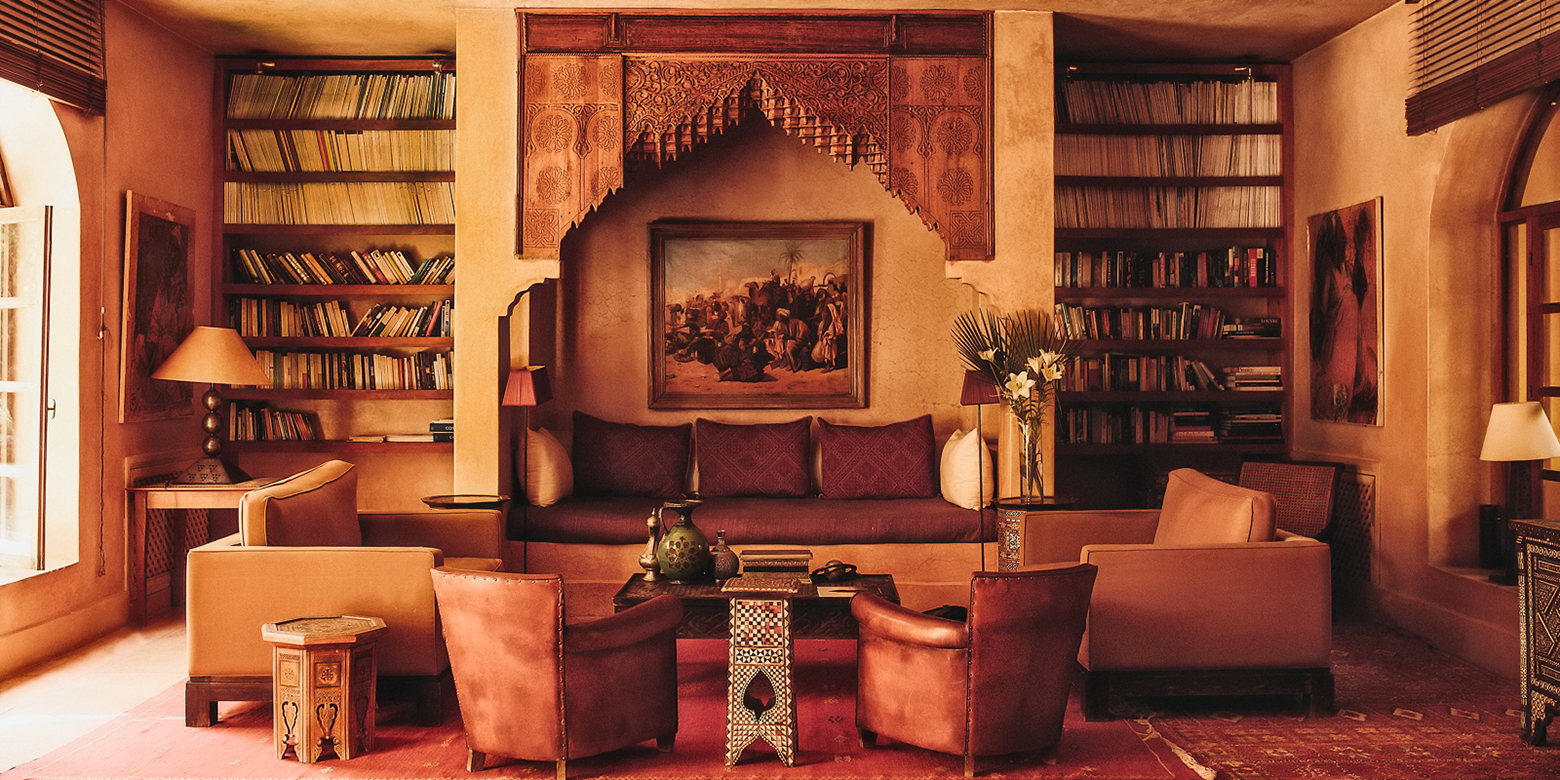

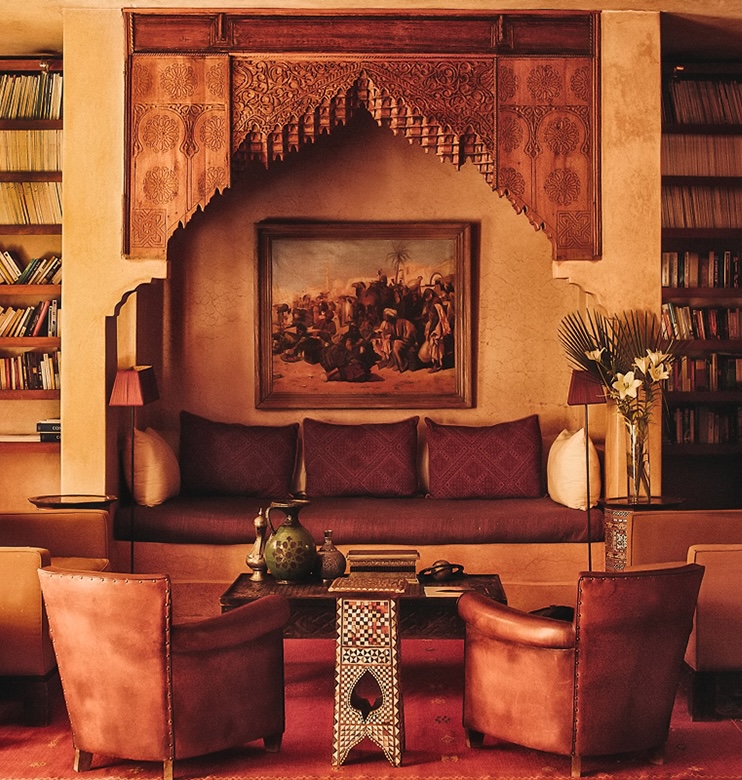

The first thing you notice at Jnane Tamsna is not the hush—though the hush is real, and practiced, the way luxury hushes are. It is not even the scent of orange blossom and warmed earth that hangs in the Palmeraie air like a private note. It is the conviction. The property feels composed rather than decorated; arranged rather than merely furnished. Every room appears to have been argued into existence—color against color, texture against texture, Morocco against the broader world and then back again—until the whole place becomes a thesis you can sleep inside.

That sensibility belongs to Meryanne Loum-Martin, the founder-owner and designer of Jnane Tamsna, a boutique hotel set in Marrakech’s Palmeraie, built across multiple houses and anchored by gardens that are, in the truest sense, an ecosystem. The hotel describes itself as a compound of five houses with five pools, a tennis court, and 24 individual rooms, with additional private villa rentals and options for full exclusivity for events. That inventory list reads like hospitality copy; on the ground, it is a map of how Loum-Martin thinks: hospitality as architecture, and architecture as a social practice.

In the international travel imagination, Marrakech has long been presented as a sensory feast—souks and lantern light, tilework and riads, the glamour of the medina filtered through a thousand Instagram reels. But Loum-Martin’s project has always been slightly angled away from Marrakech-as-postcard. She builds instead toward Marrakech-as-crossroads: Arab and Amazigh histories, West African and Caribbean inheritances, French and global design currents, and the long, complicated story of how Blackness moves through North Africa—visible, invisible, welcomed, exoticized, or ignored depending on who is doing the looking.

Jnane Tamsna’s reputation has traveled widely. It has appeared in major lifestyle and travel conversations, including coverage that frames Loum-Martin as a tastemaker and Marrakech authority. The MICHELIN Guide profiled her as the owner behind a “modern tranquility” that is also deeply personal. Architectural Digest, in the context of her Rizzoli book on Marrakech interiors, situates her as a guide to the city’s “mesmerizing style” and design lineage. And Black media outlets have treated the hotel as a milestone: Ebony’s conversation with Loum-Martin frames Jnane Tamsna as more than a five-star experience—an idea about African luxury and cultural pride.

Yet to call it simply a “Black-owned hotel in Morocco” risks shrinking what it actually is. Jnane Tamsna is Black-owned, yes—Loum-Martin is frequently described as Morocco’s only Black woman hotelier, and the hotel is widely cited as Morocco’s first Black-owned boutique hotel. But it is also a long-running, carefully sustained institution that has had to survive the realities behind the romance: the pressures of building on deadline, managing labor and supply chains, sustaining gardens in a warming climate, and operating a high-touch luxury business in an industry where “authenticity” is often a marketing synonym for extraction.

To understand why Loum-Martin’s work resonates—particularly for Black travelers and Black creatives—you have to see how deliberately she refuses to separate aesthetics from ethics, or pleasure from meaning. For decades, Marrakech has been a place where outsiders arrive to “discover” Morocco. Loum-Martin, by contrast, offers a place where Blackness is not an afterthought in the discovery narrative. It is part of the design brief.

A life built across borders

Loum-Martin’s public biography is often told as a series of pivots that look, in retrospect, like a single line: a trained lawyer in Paris who becomes a hotelier in Marrakech; a woman with corporate credentials who chooses the tactile intelligence of interiors and gardens. Multiple profiles emphasize this transition—“lawyer turned boutique hotelier”—as shorthand for her reinvention.

But “reinvention” can be too clean a word for a life formed across geographies and identities. Condé Nast Traveler’s 2025 Women Who Travel Power List describes Loum-Martin’s childhood as shaped by exposure to different cultures, with family ties that include Senegalese and Guadeloupean ancestry and a youth spent partly in France. A Shoppe Black profile similarly describes her as carrying multiple inheritances—West African and Caribbean—and building a sensibility that refuses narrow categories.

This layered identity matters in Morocco, where the public story of national culture can flatten the country into a North African monolith—Arab and Amazigh, Islamic and Mediterranean—while downplaying Morocco’s long connections to sub-Saharan Africa and the lived presence of Black Moroccans and African migrants. Loum-Martin does not posture as a sociologist. She does something arguably more potent: she builds a place that makes the “crossroads” claim unavoidable, because you can see it in the textiles, in the art choices, in the way a room’s palette nods to Senegalese weaving alongside Moroccan craft, and in the books that guests pull off shelves.

Architectural Digest’s coverage of her work underscores that she mixes pieces from around the world, including textiles by Senegalese artist Aïssa Dione, and incorporates furnishings of her own design in the home that doubles as the guesthouse. This is not eclecticism as trend; it is eclecticism as autobiography.

In interviews, Loum-Martin often frames Marrakech as a catalyst—an environment that gave her “incredible freedom” to develop her creativity. That phrasing suggests something specific: not merely inspiration, but permission. If Paris law offered rules, Marrakech offered room.

Jnane Tamsna as an argument about “African luxury”

To build a boutique hotel is to enter a crowded market of claims. Everyone promises “authenticity.” Everyone sells “oasis.” In Marrakech especially, where luxury hospitality has expanded for decades, the language of retreat can become interchangeable.

What distinguishes Jnane Tamsna, even in the most promotional accounts, is the insistence that luxury here is not imported. Shoppe Black, in a feature explicitly framing the property through Black ownership and Black cultural production, describes Jnane Tamsna as a “cultural sanctuary” and a living example of “authentic African luxury,” emphasizing that Loum-Martin created more than a hotel. Travel Noire similarly positions the hotel as Morocco’s first Black-owned hotel and notes its recognition through MICHELIN Guide inclusion, treating that validation as both symbolic and material within the travel industry’s status hierarchy.

The MICHELIN Guide’s own profile of Loum-Martin reads as a conversation with a hotelier whose sensibility is inseparable from the hotel’s atmosphere—an “oasis” built around tranquility that still carries a point of view. In other words: not just service, but authorship.

That authorship is clearest in the interiors. In a typical luxury property, design can feel like a neutral backdrop meant not to disturb the guest’s fantasy. At Jnane Tamsna, the design is the fantasy—and also the curriculum. Guests are invited into a space where African art, global modernism, Moroccan craft, and diasporic references are not separated into “influences” and “accents,” but braided.

This approach aligns with Loum-Martin’s parallel career as an author and design commentator. Architectural Digest’s “AD Aesthete” episode about her book Inside Marrakesh: Enchanting Homes and Gardens frames her as someone who can narrate the city’s design lineage—Arab, Berber/Amazigh, French Art Deco, and more—while situating Marrakech in a global creative subconscious. That kind of literacy becomes hospitality strategy: guests don’t just consume Marrakech; they learn how Marrakech has been constructed, interpreted, and sometimes appropriated.

Ebony’s coverage is especially revealing because it centers Black readership and asks what it means for a Black woman to be the founder and designer of a luxury Moroccan property. The framing is not only aspirational; it is corrective. Jnane Tamsna becomes an instance where Black taste is not a guest in someone else’s house. It is the house.

The garden as co-author

Many hotels have landscaping. Jnane Tamsna has a garden system that reads like a second narrative track. The property’s official description credits “Gary Martin’s serene nine-acre garden” alongside Loum-Martin’s interior design, making the garden not a supporting feature but a co-equal element of the hotel’s identity.

That Gary Martin is described in multiple sources as an ethnobotanist and the founder of the Global Diversity Foundation adds another layer: the garden here is not simply ornamental; it is informed by ecological and cultural knowledge.

The Guardian’s travel coverage of Marrakech gardens highlights Jnane Tamsna as an “unusual guesthouse” where “nature is encouraged to flow in and around the buildings,” noting choices such as avoiding lawns due to water intensity and maintenance challenges, and describing how various species flourish on the grounds. Even allowing for the lyrical tone typical of travel writing, this detail matters: a garden in Morocco is never just aesthetic. It is water policy. It is labor. It is a bet against aridity.

In the broader Marrakech tourism narrative, the Palmeraie is often sold as timeless: palm groves, desert light, a retreat just beyond the city’s bustle. The Guardian also notes the Palmeraie’s gentrification—how parts of “old, red Marrakech” have changed—and places Jnane Tamsna inside that story as a location where guests dine amid groves. In other words, the hotel is not outside modern tourism; it is part of the development arc that reshaped the area.

This is where any responsible account has to hold two truths at once. A property like Jnane Tamsna can be a sanctuary and a participant in gentrification pressures; a keeper of biodiversity and a consumer of water; a platform for local artisans and a luxury space priced beyond local reach. The question is not whether these tensions exist—they do—but how consciously the hotel navigates them, and how transparently it tells its own story.

Morocco, Blackness, and the politics of “being the only one”

Many articles describe Loum-Martin as Morocco’s only Black woman hotelier. That phrase is powerful, but it also carries a quiet burden: the burden of representation. To be “the only one” is to become a symbol whether you asked for it or not.

Condé Nast Traveler notes that Loum-Martin “was never aiming to be the first of anything,” positioning her work as an expression of self rather than a quest for novelty. The distinction matters because tourism media often reduces Black achievement to “firsts,” using milestones as feel-good punctuation while skipping the daily grind of business building.

The grind is present in long-form interviews and podcasts where Loum-Martin speaks more candidly about pressure, deadlines, and the practical demands of opening and sustaining a property. Podcast conversations about her work—circulating through business and entrepreneurship audiences—underscore the arc from law to hospitality and the realities behind the brand.

What emerges across sources is a portrait of a woman who built authority in a field where authority is often gatekept through networks of legacy wealth, European ownership, and the presumed neutrality of “international taste.” Loum-Martin flips that presumption. Her taste is not neutral. It is specific, and that specificity is what draws the “boho crowd of artists and writers” the hotel itself mentions.

For Black travelers, that specificity can register as relief. Not because the hotel is marketed as “for Black guests only”—it is not—but because it does not treat Blackness as an anomaly in the luxury frame. Several Black travel and culture outlets describe Jnane Tamsna as a place where Black culture and diaspora creativity are welcomed and centered through events and programming, including writers’ retreats.

Even if one sets aside the promotional tone common to such pieces, the cultural implication remains: in a global travel economy where Black tourists often have to research safety, belonging, and racial dynamics as part of itinerary planning, a Black-owned luxury property can function as infrastructure. It becomes a base of confidence.

The hotel as salon, not just lodging

The most interesting luxury hotels do not merely host guests; they host meaning. They become salons—places where people come to be around other people, and where conversation feels like part of the amenity list.

Jnane Tamsna’s orbit includes writers, artists, designers, and cultural producers, and this is not incidental. The hotel’s own positioning—art, gardens, architecture, design—reads like a curatorial statement. Shoppe Black’s coverage of writers’ retreats makes this salon aspect explicit, describing the property as a venue for Black authors and creative convening.

That “salon” function is echoed in lifestyle coverage that treats the hotel as a stage for themed gatherings—high-aesthetic events that still hinge on community. AphroChic, for example, recounts a multi-day celebration hosted at Jnane Tamsna that leaned into pageantry and performance—costumes, music, spectacle—suggesting the property’s capacity to hold not only rest but ritual.

It is tempting to dismiss such accounts as social-media-era fluff. But salons have always had an element of performance. The point is the gathering: who is invited, what conversations are possible, what kind of cultural confidence is produced when people see themselves reflected in the room.

In the standard Marrakech luxury narrative, the reflected image is often European: expatriate aesthetics, imported minimalism, the romance of “escaping” to Morocco. Loum-Martin offers a different reflection: a diasporic confidence that treats Morocco not as a fantasy backdrop but as part of a broader African story.

Marrakech as muse—and as marketplace

Any serious profile of a Marrakech hotel has to contend with Marrakech itself: a city that has been branded, sold, and resold, sometimes at the expense of local affordability and authenticity. Travel writing has long contributed to this myth-making; so has high-design publishing.

Loum-Martin participates in that system—she is a published author on Marrakech homes and gardens, featured by Architectural Digest and others. But she also seems aware of the hazards of the Marrakech aesthetic becoming a consumable costume. Her own itinerary feature for Condé Nast Traveler reads like a map of the city’s design and artisan districts, including Sidi Ghanem, galleries, and museums—a guide that treats Marrakech as a living creative economy rather than a set.

This is where Loum-Martin’s dual identity—insider-outsider, resident with global vision—becomes a strategic advantage. She can speak to visitors in the language they already understand (design, curation, “best of”), while still pushing them toward a deeper engagement with Moroccan makers and institutions.

For readers interested in the economics behind the romance, one question matters: how does a boutique hotel create local value rather than simply extracting it? No single source provides a full accounting of Jnane Tamsna’s supply chain or employment practices. But the repeated emphasis on artisanry, gardens, and cultural programming suggests an operational model that depends on local skill and long-term relationship building—particularly in the labor-intensive domains of groundskeeping, maintenance, cuisine, textiles, and guest experience.

That said, the broader luxury market in Marrakech has well-documented issues—from precarious tourism employment to development pressures—so it is important not to confuse aesthetic celebration with structural justice. The most honest reading is that Jnane Tamsna represents an intervention in who gets to be an owner and an author in Morocco’s luxury landscape, while still operating inside the constraints and contradictions of luxury tourism as an industry.

Recognition, and what recognition buys you

In hospitality, awards and lists are not mere ego; they are distribution. They affect booking pipelines, partnerships, and cultural clout.

Jnane Tamsna’s inclusion in MICHELIN Guide conversations and its coverage by MICHELIN Guide editors function as a type of legitimization in a global market that still leans heavily on European arbiters of taste. Likewise, Condé Nast Traveler’s Power List placement situates Loum-Martin among global women reshaping travel, placing her in a lineage of travel-as-values rather than travel-as-consumption.

But perhaps the more meaningful recognition is the one that cannot be badge-engineered: repeat guests, word-of-mouth, the way artists and writers use a place as a reference point. The hotel’s reputation as a bohemian refuge is longstanding enough to appear even in older travel discourse.

And then there is the subtler kind of recognition: the way a place changes what travelers believe is possible. For Black entrepreneurs and Black creatives, a Black-owned luxury hotel in Morocco carries an aspirational charge—not because it is rare, but because it reveals how many such projects could exist if ownership pathways were less constrained by race, capital access, and global gatekeeping.

The future of Jnane Tamsna—and the question it leaves behind

A hotel is never finished. It is maintained into being, day after day, through labor that guests are trained not to notice. The sheets appear clean as if by magic; the gardens look effortless; the air smells like calm. But calm is constructed.

What Loum-Martin has constructed at Jnane Tamsna is a rare blend: a luxury property that operates as a design manifesto, a diasporic salon, and an ecological proposition, all at once. The hotel’s own language stresses its integration of houses, pools, and gardens; the journalism around it stresses something harder to quantify—presence, identity, authorship.

If you take seriously the idea that hospitality can be cultural infrastructure, then Jnane Tamsna is not just a destination. It is a tool: a tool for convening, for aesthetic education, for diasporic grounding, for rest that does not require self-erasure.

And that may be Loum-Martin’s most significant accomplishment: not that she built an oasis, but that she built an oasis with a thesis—one that quietly asks every guest, upon arrival, to consider who usually gets to design the dream.