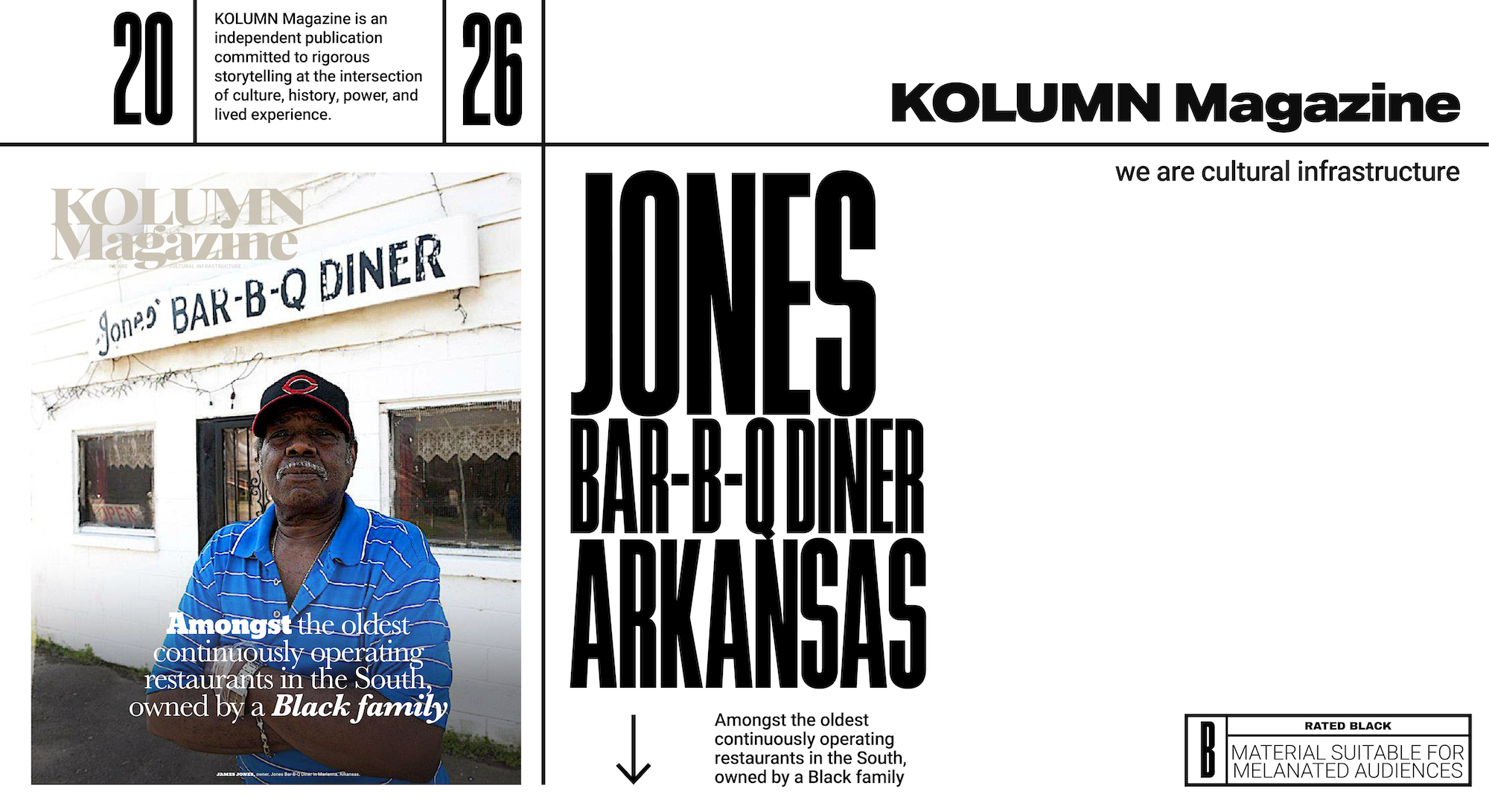

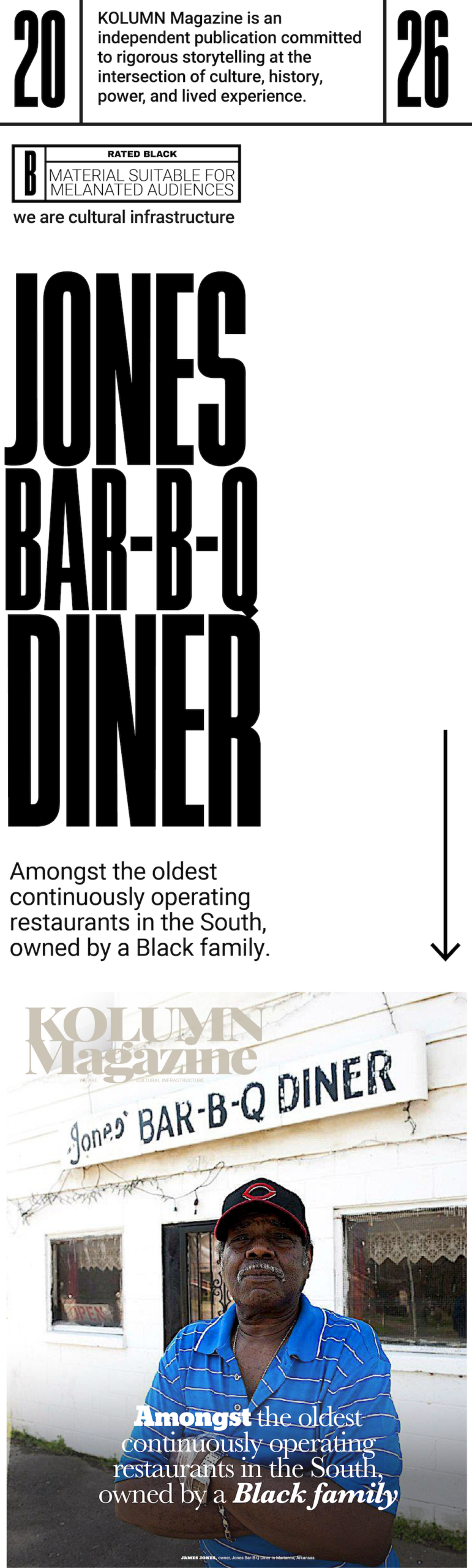

KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a morning when the Arkansas Delta air hangs heavy—humid in summer, metallic and sharp in winter—Marianna wakes in small increments. A door opens. A car idles. Someone crosses a yard that has known the footfalls of decades. And then, almost as if the town is obeying an older clock than the one on the courthouse square, people begin to drift toward a modest building on West Louisiana Street.

The place does not announce itself the way modern “destinations” do. No curated facade. No choreographed signage. No careful storyboards of authenticity. What it offers is both simpler and, in an American sense, rarer: continuity.

Jones Bar-B-Q Diner is a two-table restaurant that has been serving some version of the same meal since the 1910s, with the Jones family maintaining ownership across generations. It is “perhaps the oldest continuously operating restaurant in Arkansas,” and “perhaps the oldest continuously operating restaurant in the South owned by a Black family,” according to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas. The phrase “perhaps” matters—because precise documentation for Black enterprise in the early twentieth century was never as systematic as it was for the institutions that controlled Black life. But the weight of testimony, journalism, and institutional recognition points in the same direction: Jones is among the oldest Black family–owned restaurants in America, and it is widely described—sometimes with careful qualification, sometimes without—as the oldest Black-owned restaurant in the country.

Its menu, famously, is an argument against the modern compulsion to multiply. The Encyclopedia of Arkansas describes it plainly: chopped pork by the pound or on a sandwich, with or without slaw—brought fast, eaten faster, remembered longest. The sandwich comes on white bread; the meat is chopped fine and dressed with a tangy, slightly sweet vinegar-based red sauce; the slaw is mustard-based and light. The restaurant closes when the meat runs out, which is often late morning on busy days—customers arrive as early as 7 a.m. to make sure they get it.

What you taste at Jones is not just pork and smoke. It is a set of decisions—economic, social, and moral—made by Black proprietors who understood, in their bones, that ownership was never merely a business category. In the Arkansas Delta, ownership could be a provocation.

And that is the story beneath the sandwich: the biography of Walter Jones, the founding pitmaster remembered as a “barbecue trickster” of uncommon skill; the family succession that turned a porch operation into a landmark; and the hard, quiet discipline it took for the Joneses to keep control of their name and their pit through Jim Crow, through the fraying aftermath of civil rights victories, through the slow violence of rural disinvestment—and, most recently, through literal fire.

Walter Jones, the first pitmaster: A life in smoke and witness

Walter Jones is not the kind of founder America typically elevates in its business mythology. There are no glossy portraits of him on corporate anniversary walls. No TED Talk about “disruption.” What survives instead is something closer to folk memory—accounts shared across races and generations in Marianna, stitched together by writers who understood that in the South, the archive is often oral before it is written.

The Encyclopedia of Arkansas identifies Walter Jones as the restaurant’s first owner and pitmaster, situating the diner’s beginnings in the 1910s and naming the earliest downtown iteration “The Hole in the Wall.” John T. Edge, writing in the Oxford American, pushes that origin deeper into lived detail: Walter Jones selling barbecue from the back porch of a dogtrot house on Fridays and Saturdays, the building “unpainted, just bare wood,” the eating mostly take-away because there was “no real place to eat.”

Edge’s reporting captures Walter Jones as a figure both admired and mythologized. An older resident recalls him “in a cloud of smoke with a bottle of sauce in his hand.” This is not sanitized entrepreneurship; it is the portrait of a working-class Black man operating a business in a world where Black autonomy was circumscribed by law, custom, and threat.

The early cooking setup, as recalled by the family in a 1986 local history compilation cited by Edge, was as stripped-down as necessity demanded: “a hole in the ground, some iron pipes and a piece of fence wire and two pieces of tin.” That description does more than conjure an image. It locates Jones in a tradition of Black Southern pitcraft—techniques rooted in resourcefulness, communal feeding, and the long history of cooking over fire with whatever materials could be assembled.

In the early years, whole hog was standard; the meat was hacked from the carcass, pulled into sandwich portions, and sold from a metal roasting pan set on a kitchen table, Edge reports. If you wanted sauce, an older patron recalled, you brought your own bottle and Walter filled it. You could get certain parts—skins, ears, tails—sometimes for free.

That exchange—bring your own container, leave with something sustaining—sounds almost quaint until you place it where it belongs: in the Arkansas Delta, where Black labor underwrote a cotton economy and Black consumers were often forced into inferior markets, inferior service, and inferior credit. In that landscape, the simple act of a Black man selling a product valued across the color line carried a volatile charge. Barbecue, Edge notes, was one of the few pleasures that moved across segregation’s boundaries—yet even that movement had terms.

Edge’s essay is blunt about the racial choreography that undergirded “integrated” consumption. He describes the phenomenon of whites seeking out Black pitmasters through “back-door patronage”—an arrangement in which desire for the food did not necessarily translate into respect for the people producing it. In other words: in the Jim Crow South, a white customer could crave Black-made barbecue while still supporting the very social order that limited Black mobility. This is one of the enduring contradictions of American appetite: it can be intimate without being just.

Walter Jones, then, was not merely cooking. He was navigating an economy where Black excellence could be exploited, appropriated, or enjoyed at arm’s length—praised in private, denied in public.

From “The Hole in the Wall” to a home on Louisiana Street

If Walter Jones is the origin story, the family’s second act is the less romantic, more structurally significant work of turning a practice into a place.

Accounts differ on the precise early geography, but they align on a basic arc: a downtown Marianna operation known as “The Hole in the Wall,” followed by a move to the restaurant’s current location in 1964, when the business took the Jones Bar-B-Q Diner name.

That year—1964—is a hinge in American history, and it matters that Jones’s physical relocation happened as the Civil Rights Act redefined public accommodations in law, even as local life in many places changed unevenly, slowly, and sometimes violently. The Jones family’s decision to operate out of a modest, home-like structure—a white cinderblock shotgun building with an upstairs apartment—reads as practical. But it also reads as strategic: a way to embed the business in a neighborhood, to own the space outright, to keep the enterprise close to the family’s daily life and therefore less exposed to the kinds of external control that had historically gutted Black businesses.

The Oxford American describes the building in tactile terms: lace drapes in the windows, wrought-iron on the storm door, and always, “a thin feather of smoke” trailing from a chimney. The dining room is small; service happens through a square window that, in Edge’s telling, evokes both ticket booths and confessionals—an image that unintentionally captures something true about eating in the South: you come to the window with your desire, your money, your timing, and you receive what the pit has decided to give.

This physical modesty has often been misread by outsiders as quaintness. But in Black-owned foodways, modesty can be a form of insulation. If you build a spectacle, you invite surveillance. If you build a system so simple it appears almost stubborn, you reduce the number of moving parts that can be taken from you.

Jones became famous, in part, because it resisted the era’s typical arc: expansion, franchising, menu diversification, brand partnerships. The Jones family did something else. They stayed.

The third and fourth generations: James Harold Jones, Betty Jones, and the discipline of continuity

By the time national media began calling Jones Bar-B-Q Diner a pilgrimage site, the pit was in the hands of James Harold Jones, a grandson of Walter Jones, and his wife, Betty. The Encyclopedia of Arkansas identifies James Harold Jones as the pitmaster. The Oxford American depicts him as gray-haired, watchful, working the counter and protecting the flow of meat.

The mechanics of the place are, at first glance, almost aggressively unmodern: cook three days a week; sell sandwiches until you run out; close early when the last shoulder is chopped. The point is not inconvenience; it is control. In a rural economy where small businesses often die by a thousand costs—inventory, staffing, utilities, rent—Jones narrows the business to what it can execute perfectly.

James Beard Foundation recognition helped translate that mastery for a national audience. Jones Bar-B-Q Diner was designated an “America’s Classic” by the James Beard Foundation in 2012—an honor often used to recognize locally owned institutions with enduring community significance. The Encyclopedia of Arkansas notes that until 2012, no person or place in Arkansas had received a James Beard Award, making Jones the state’s first recipient. In 2017, the restaurant was inducted into the Arkansas Food Hall of Fame’s inaugural class.

For the Jones family, national honors did not erase the local realities that had always defined the business. Marianna is the seat of Lee County, a place the Oxford American describes as poverty-stricken, with a downtown that weakened over decades. In such contexts, a restaurant is not merely a place to eat; it can become a kind of informal civic institution—where people check in, exchange news, and participate in a ritual that gives the town a pulse.

This is a quieter form of legacy than the one American culture usually celebrates. It is not “empire building.” It is “maintenance,” which is often dismissed until it disappears.

The racial history around the pit: Appetite under segregation, and the cost of being indispensable

To write about Jones Bar-B-Q Diner honestly, you have to describe the racial atmosphere it survived—not as background color, but as a shaping force.

Marianna sits in the Arkansas Delta, a region defined by plantation agriculture, entrenched segregation, and the long afterlife of systems designed to extract Black labor while limiting Black power. In such places, Black business ownership was precarious by design: credit could be withheld, supplies disrupted, permits delayed, threats tolerated.

Jones endured in part because barbecue occupied a strange position in the Jim Crow social order. White customers might seek out Black pitmasters’ food even when they would not share a table with Black families elsewhere. The Oxford American explicitly complicates the mythology of barbecue as a purely unifying Southern tradition, arguing that “back-door patronage” often allowed white patrons to indulge without challenging the broader racial hierarchy.

This is one of the central tensions of the Jones story: Jones Bar-B-Q Diner could be “relatively integrated” as a site of consumption even while the county remained governed by segregation’s logic. In practice, that meant Black labor producing something white patrons wanted—sometimes deeply—without that desire necessarily translating into shared power or equal regard.

There is also the matter of vulnerability. Edge reports James Jones describing theft—people cutting into the building at night, attempting to steal meat “straight off the grill,” even trying to take a whole hog; they could not lift it, but they left with shoulders. On one level, that is a crime story. On another, it is an illustration of what it means to run a food business where your product has value and your resources for protection are limited. In rural America, and particularly in Black rural America, being known can make you a target.

The Jones family’s resilience is often narrated as romance—“a century-old joint still doing it the old way.” But the lived experience was more complicated: guarding supplies, managing unpredictable demand, operating in a region where racial prejudice could restrict opportunity while simultaneously rendering Black cultural production “essential” to the broader community’s pleasure.

A wider Delta context: Civil rights, economic control, and what a restaurant represents

Even when a restaurant is not explicitly political, it lives inside politics—especially in small towns where ownership patterns map cleanly onto race.

Edge points to a 1971 boycott in Marianna in which Black citizens, seeking economic leverage against a white oligarchy, boycotted white-owned downtown businesses for a year. The spark, he notes, was an argument over pizza service for a Black patron at a local drive-in—small on its face, enormous in implication.

Why does that matter for Jones? Because boycotts and economic campaigns are, at base, about where money is allowed to go. A Black-owned restaurant that survives across eras becomes, by default, a rebuttal to the idea that Black enterprise is temporary or marginal. It becomes a place where Black money can circulate on Black terms—where the Jones family sets the rules: the hours, the menu, the portion, the pace.

This autonomy is not a sentimental value. It is a material one. It is what allows a business to be passed on.

Fire, rebuilding, and the modern era’s version of fragility

On February 28, 2021, Jones Bar-B-Q Diner caught fire. For a business that had already beaten the odds for a century, the loss was almost too on-the-nose: the pit, the very heart of the place, becoming the source of devastation.

Yet the response to the fire revealed something else Jones had built over the decades: a network of affection that extended far beyond Marianna. Coverage at the time described extensive damage and plans to rebuild; supporters raised money for restoration. The Encyclopedia of Arkansas reports that funds were raised and that the diner held a grand reopening on July 14, 2021.

The fire story is sometimes told as a feel-good coda—community rallies, landmark returns. But it also underscores the fragility that never goes away for small, family-run businesses, especially ones in rural areas. One disaster can end a century.

That Jones reopened is not merely a triumph of will. It is an example of what can happen when cultural institutions are treated as worth saving—not because they are trendy, but because they are foundational.

The sandwich as a historical document

It is easy, in food writing, to over-romanticize. To treat taste as pure memory, unburdened by context. Jones does not allow that luxury.

When you describe the Jones sandwich accurately—white bread, chopped pork, vinegar-red sauce, mustard slaw—you are also describing a Black Delta aesthetic: practical, direct, engineered for feeding people who may have had little time and less money, but who demanded flavor anyway.

The consistency of the product is part of the cultural argument. It says: this is what we do, and we do not need to perform novelty to justify our existence. In a country that often treats Black institutions as “new” the moment white audiences discover them, Jones quietly insists on its own age.

The Jones family also maintained something even harder than a recipe: a system of labor. Pit barbecue is not casual cooking. It is time discipline, sleep discipline, heat discipline. In Edge’s telling, James Jones sleeps upstairs on cook nights because the pit demands attention. There is a line in that essay—simple, almost tossed off—that reads like a thesis: James Jones says he cannot remember when he didn’t smell like smoke. That is what legacy often looks like in Black family enterprise: not a neat inheritance, but a scent that clings.

“Oldest” and the burden of proof in Black enterprise

This is not pedantry. It is part of the story. The uncertainty is itself an artifact of American racial history: record-keeping, capital access, and institutional recognition were not distributed evenly. So when Jones is described as the oldest, what is also being acknowledged is how extraordinary it is that any Black family business from that era can still be traced, still visited, still tasted.

In that sense, “oldest” is less a trophy than a diagnosis: it tells you how many others did not survive the same century.

How the family maintained ownership: control, simplicity, and refusal

If you ask what, precisely, kept Jones in the Jones family, the answers are not glamorous—but they are instructive.

First: control of the asset. The move to the current location in 1964—and the family’s long operation from that building—placed the business inside a physical footprint that reads like family property rather than commercial lease. In Black business history, control of the premises can be the difference between permanence and vulnerability.

Second: radical simplicity. The menu is narrow by design, the hours are dictated by production, and the restaurant closes when it sells out. This is a model that prioritizes execution over scale and protects the family from the financial and operational risks that kill small restaurants.

Third: guarded craft. The pit method, the sauce profile, the slaw—these are forms of intellectual property held in family practice. The value is not only the ingredients; it is the technique and the repetition.

Fourth: local embeddedness. The restaurant matters in Marianna not as a novelty but as a fixture—something the Encyclopedia of Arkansas emphasizes when it notes Jones’s importance in the rural community even as it draws enthusiasts from around the world. A business that is woven into local routine can outlast economic swings that destroy places built only for visitors.

And finally: refusal. Refusal to expand in ways that would dilute control. Refusal to make the food legible to outsiders by changing it. Refusal, in a racial context, to perform gratitude for being tolerated.

What Jones Bar-B-Q Diner means now

In the last decade, America has rediscovered Black food institutions with a mix of reverence and opportunism—placing them on lists, turning them into content, building tourism narratives around them. Jones has appeared in travel and barbecue coverage, and it continues to be framed as a landmark worth the drive, if you can arrive before it sells out.

The risk, for any such institution, is that fame can become a new kind of extraction. Not necessarily through theft—though Edge’s account reminds us that theft is literal too—but through the subtler pressure to become something else: bigger, faster, more accessible, more Instagrammable, more scaled.

The Jones family story, at its best, stands as a counterexample. It argues that longevity can be its own modernity—that a Black-owned business does not have to transform into a facsimile of corporate hospitality to be worthy of acclaim.

If you want to understand why Jones Bar-B-Q Diner matters, you can start with the accolades: a James Beard America’s Classic designation; statewide firsts; hall-of-fame inductions; the way national media returned to the story after the fire and the reopening.

But you will end, inevitably, with something smaller: a service window; a measured scoop of chopped pork; sauce squeezed from a bottle; slaw applied with restraint; white bread folding under heat. And the knowledge that the act of buying that sandwich—so ordinary it can be finished in minutes—connects you to a century of Black family work in a region that did not promise Black families longevity.

In Marianna, the line forms early. The pit does what it has always done. The Jones name remains on the building. And the most radical thing about the place is that it is still there.