By KOLUMN Magazine

Editor’s Note: The next edition in KOLUMN Magazine’s 2025 remembrance series

This is the second installment in KOLUMN Magazine’s three-part remembrance project honoring Black lives lost in 2025—meaning-makers and memory-carriers whose work shaped how the country moves, votes, mourns, negotiates, and tells the truth about itself. After Arts & Entertainment, this edition turns toward Activism and Public Service: the elected officials, institution-builders, movement figures, and public-intellectual voices who treated democracy as a daily practice rather than a slogan. The final edition—Sports—will follow.

A year that asked the public to remember what it runs on

The United States has an odd habit of treating public service as background noise—present until it fails, invisible until it becomes scandal, forgotten the moment the next cycle begins. But 2025 made the cost of that amnesia difficult to ignore. This was a year when the people who often held the system together—sometimes from the inside, sometimes from the outside, sometimes from exile—left the stage.

Some were elected officials whose reputations were built in the long middle: committee hearings, constituent calls, late-night compromises that never make it into campaign footage. Some were activists who lived in the country’s unresolved arguments about justice, law, and legitimacy. Some were builders of Black institutions—magazines, clinics, public narratives—who understood that representation is not cosmetic; it is infrastructure.

These lives—Barry Michael Cooper, Retired Lt. Col. Harry Stewart Jr., Dr. Alvin Poussaint, Sylvester Turner, Mia Love, Clarence O. Smith, Alexis Herman, Charles Rangel, Assata Shakur, Jamil Al-Amin, and Viola Ford Fletcher—tell that story in different keys. Taken together, they read like a civic syllabus: what America asks of Black citizenship, and what Black Americans have insisted America can still become.

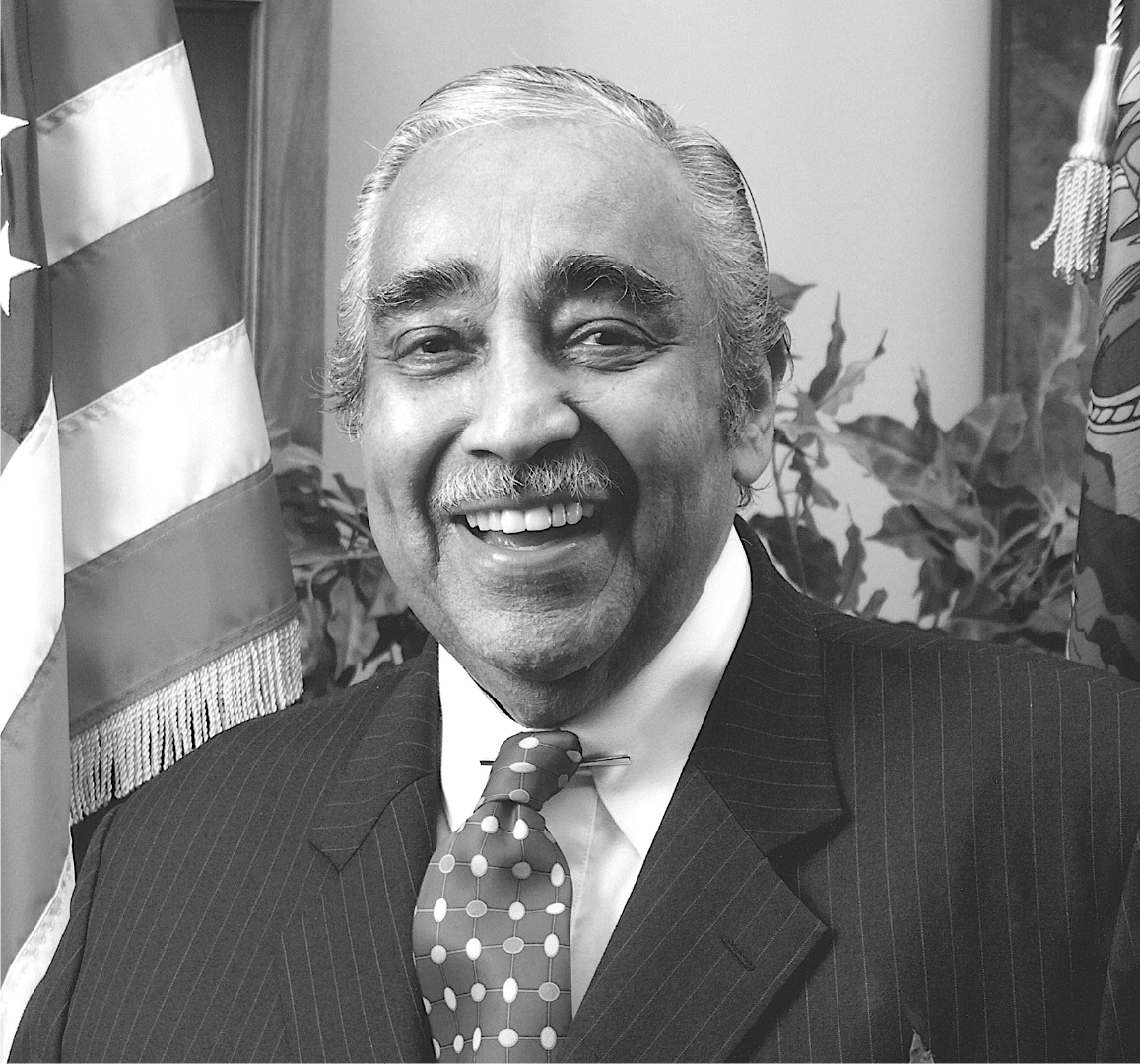

Barry Michael Cooper: the cultural reporter who treated the street as public record

Barry Michael Cooper is sometimes introduced through the films—New Jack City, Sugar Hill, Above the Rim—as if his life begins the moment Hollywood notices. But his real origin story is journalistic: a Black writer from Harlem who understood that the crack era was not merely a “crime wave,” but a policy story, a public-health story, a housing story, an economic story—and that the people living inside it deserved to be described with specificity rather than stereotype. Cooper died in January 2025 at 66.

He was born in Harlem and grew up in New York City, in neighborhoods where culture and survival were braided tightly enough that a block could function like a newsroom. His childhood was shaped by the social churn of a city that could be both brutal and brilliantly instructive. Cooper carried that double vision into his early writing: curiosity without naïveté, empathy without soft focus.

He began “performing” publicly—if we treat performance as the act of addressing an audience—through reporting. In the 1980s, Cooper wrote for outlets including The Village Voice, covering the crack epidemic and its ecosystem with a reporter’s eye for detail and a community member’s refusal to turn suffering into spectacle. The reporting mattered because it captured life as it was lived, not merely as officials described it. In a decade when Black urban communities were often reduced to pathology in mainstream narratives, Cooper insisted on sociology: the systems that produce outcomes, the incentives that make violence profitable, the ways language itself can become a weapon.

His pivot into screenwriting was less a departure than a change of format. New Jack City (1991) is routinely remembered for its star power and its quotable lines, but its deeper cultural function was to translate a set of urban realities—drug policy, policing, capitalism’s predations—into a pop-cultural text that forced a broader audience to look. Sugar Hill and Above the Rim extended that project, building what many writers call Cooper’s “Harlem trilogy,” films rooted in a specific Black geography and a specific moral tension: what do you owe your neighborhood when the economy offers you only bad options?

Cooper’s later work included contributions to contemporary media projects, signaling that his sensibility—street-level detail as civic data—did not age out. After his death, peers emphasized his influence not just on film but on cultural language: the way he helped frame late-20th-century Black urban life in the public imagination.

In a country that often treats Black communities as an abstraction to be managed, Cooper’s legacy is a form of public service: he documented the human consequences of public policy and dared to make the record vivid enough that it could not be ignored.

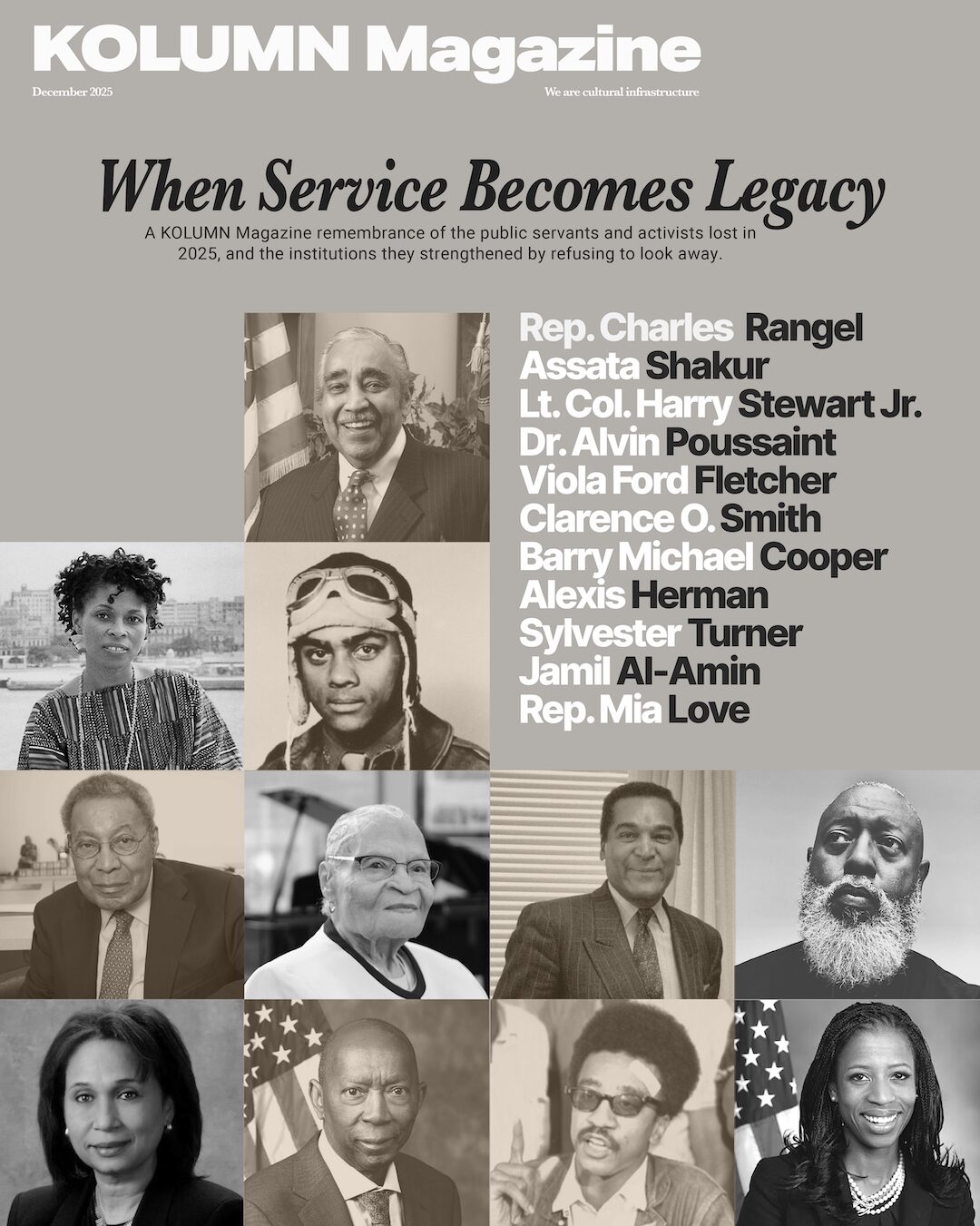

Retired Lt. Col. Harry Stewart Jr.: the pilot who defeated segregation in the sky, then met it on the ground

Harry Stewart Jr. belonged to a generation asked to prove American ideals while being denied them. As a Tuskegee Airman, he flew combat missions in World War II as part of a segregated military, defending a country that often refused to see him as fully belonging to it. He died in February 2025 at 100, one of the last surviving combat pilots of the famed 332nd Fighter Group.

Stewart was born in Newport News, Virginia, and spent parts of his childhood in New York. The details matter because they place him within the Great Migration’s broader logic: Black families moving, adapting, seeking possibility in a nation organized to ration it. He became fascinated with flight early—a dream that, for Black Americans in the early 20th century, required not only ambition but a willingness to argue with the era’s limitations.

He began his public “performance” as service—joining the military after Pearl Harbor, entering the Tuskegee training program that produced the first Black military aviators. The training itself was a confrontation with segregation: Black excellence forced to operate within segregated conditions, as if talent required quarantine. Stewart emerged as more than a graduate; he became a combat pilot with measurable success, earning the Distinguished Flying Cross and, in 1945, shooting down three German aircraft in a single day—an achievement that placed him among a small handful of Tuskegee pilots credited with such a feat.

The Tuskegee Airmen’s broader legacy is often told as symbolism—“breaking barriers”—but Stewart’s biography makes it tangible. Their escort missions became famed for effectiveness; their discipline contradicted racist assumptions in ways that could be counted, logged, verified. That measurable excellence helped shift public attitudes and fed into the larger argument for desegregating the armed forces—an argument that would become policy after the war.

Then came the second, quieter injustice. After returning from combat, Stewart was denied commercial airline opportunities because of race, a blunt reminder that heroism does not automatically purchase equality. He turned toward engineering and business, earning a degree and building a civilian career, while continuing to represent the Tuskegee Airmen’s story in public memory.

In later decades, Stewart helped preserve the record—through interviews and a memoir—because he understood how quickly the country forgets what it owes. His life demonstrates a particular American contradiction: the nation will celebrate Black service in wartime while restricting Black opportunity in peace. And yet his legacy is also a testament to endurance: he lived long enough to see his history honored, his unit recognized, and his contribution placed where it belongs—in the center of the American story.

Dr. Alvin Poussaint: the psychiatrist who made racism a clinical fact, not a rhetorical debate

Alvin Poussaint spent a lifetime insisting that racism is not simply a social problem—it is a health problem, measurable in stress, trauma, disparity, and shortened life expectancy. He died on February 24, 2025, at 90, after a short illness. The obituaries called him a Harvard psychiatrist and civil rights physician, but his larger role was as a translator: he carried Black lived experience into institutions that had long treated it as anecdote rather than evidence.

Poussaint was born in Louisiana and came of age in a Jim Crow America where the psychological violence of segregation was often dismissed as “normal.” His early education and ambition pulled him toward medicine, but his moral education was inseparable from the era’s politics. He understood, early, that the body and the society are not separate systems—that a racist world becomes a physiological environment.

He began his public service in the crucible of the civil rights movement, going to Mississippi in the 1960s to provide medical care to activists. That experience—medicine practiced under threat—helped shape his later insistence that mental health cannot be discussed without discussing power.

At Harvard Medical School, Poussaint became a force: professor of psychiatry, long-time leader in student affairs, and a central advocate for diversifying medicine and addressing health disparities. Institutional change is often narrated as committee work, and Poussaint did plenty of that, but the deeper change was cultural. He helped make it possible—within elite medical contexts—to say plainly that racism shapes outcomes.

To the broader public, Poussaint was also known through his work with The Cosby Show, advising on educational and social themes at a moment when Black family life on television was heavily burdened with representational politics. That chapter of his career underscores his range: he believed mental health work included public narrative—what the country tells itself about Black families, Black children, Black possibility.

His writings addressed the internalization of racism, violence, and the specific vulnerabilities of Black children navigating hostile systems. He became a go-to voice precisely because he refused the country’s preferred evasions. He spoke about the psychological costs of discrimination without reducing Black people to damage. In his framework, resilience was real, but so was injury—and acknowledging injury was the first step toward policy change.

After his death, tributes emphasized mentorship: the generations of doctors and advocates shaped by his example. That might be the clearest metric of his legacy. Poussaint’s work did not end with his own publications; it reproduced itself through students trained to treat Black mental health as central rather than marginal. He made the country’s moral failures legible as clinical data—and in doing so, he made denial harder.

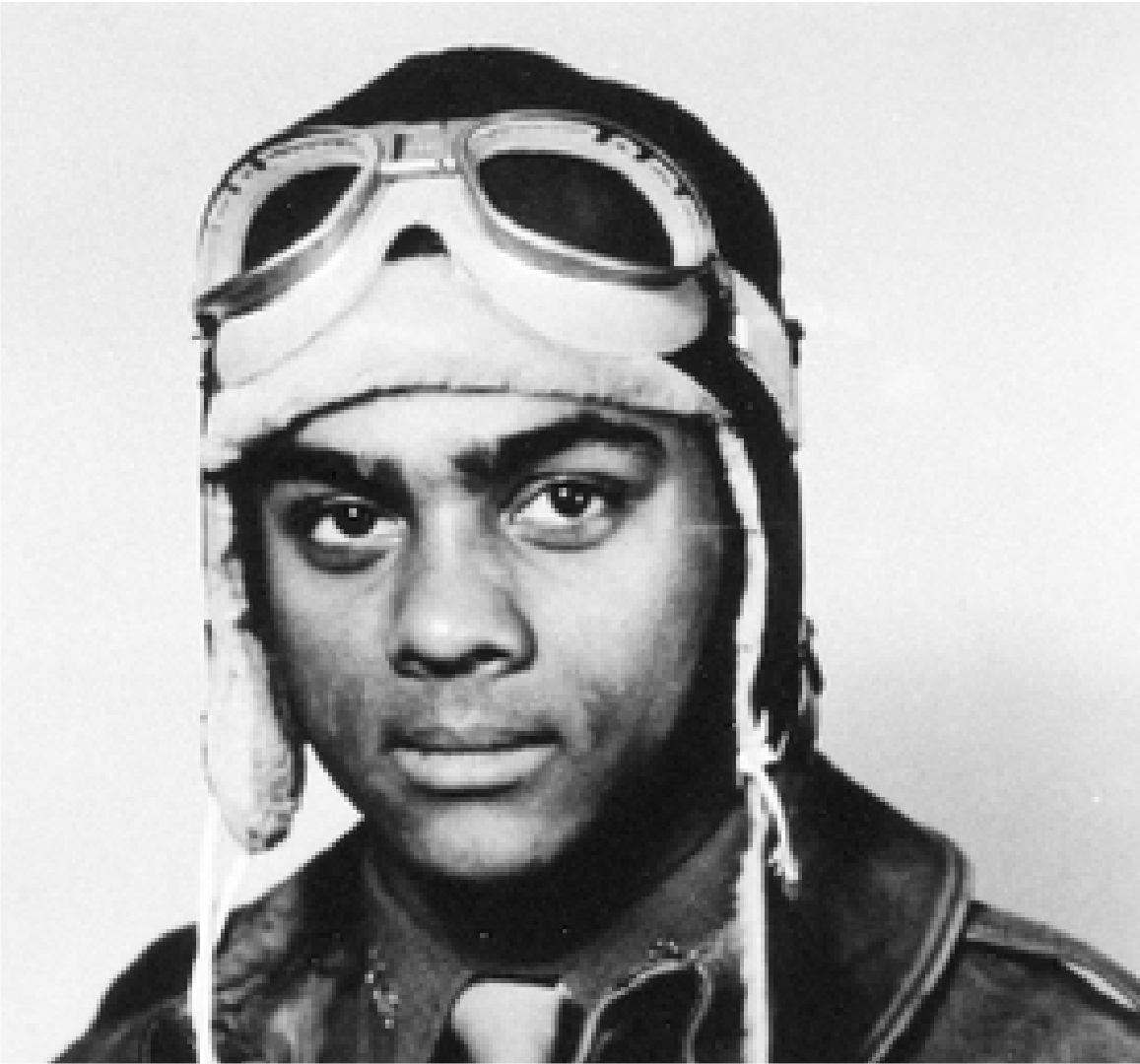

Sylvester Turner: the mayor who governed like a neighbor

Sylvester Turner’s political identity was inseparable from Houston—a city whose size and complexity require a certain kind of leadership: coalition-building as daily labor, crisis management as routine, public joy as civic strategy. Turner died on March 5, 2025, at 70, after ongoing health struggles, according to his family. He had recently begun serving in Congress after eight years as Houston’s mayor and nearly three decades in the Texas Legislature.

Turner was born in 1954 and raised in Houston’s Acres Home, a community with a strong Black identity and a tradition of self-determination. Childhood in such a place tends to teach two lessons at once: pride and precarity. Turner’s biography reflects that dual education. He rose through local institutions, building a reputation as someone fluent in the city’s textures—church life, neighborhood dynamics, the intimate knowledge of who gets left out when policies are written far away.

He began his public “performance” early in political life, entering the Texas House in the late 1980s and staying long enough to become a fixture—one of those legislators who understands that governance is built in the long middle: relationships, details, budgets, incremental wins. When he became mayor in 2016, he inherited a city that would soon face defining crises, including Hurricane Harvey. His leadership during disaster response became central to his public image: a mayor required to be both administrator and comforter.

Turner’s tenure also included the routine but consequential fights over infrastructure, policing, housing, and economic development—areas where the outcomes are often unevenly distributed along racial lines. He framed his work in inclusive terms, and supporters praised him for a style that felt personal rather than aloof. That “neighbor” quality—being known, being present—matters in big cities, where governance can easily feel like a distant machine.

In 2025, Turner had only recently taken a seat in the U.S. House, filling a storied district. His death came shortly after national events in Washington, according to contemporaneous reporting, and Houston responded with ritual: lying in state, memorials, a funeral that brought together political figures across lines.

Turner’s accomplishments are, in part, measurable—terms served, elections won. But the more telling legacy is how he embodied a particular tradition of Black municipal leadership: practical, relational, rooted in place. He rose from a historically Black community to the highest levels of local and national office without adopting the posture of distance. In an era when politics often rewards performance over service, Turner’s style suggested he still believed in the job itself.

Mia Love: a history-making conservative who carried competing symbols

Mia Love was a political figure onto whom the country projected multiple, sometimes contradictory meanings: Black Republican, daughter of Haitian immigrants, Latter-day Saint, mayor during recession, member of Congress during an era of rising polarization. She died on March 23, 2025, at 49, after a battle with brain cancer (widely reported as glioblastoma).

Born Ludmya Bourdeau in New York City on December 6, 1975, Love was raised in an immigrant household shaped by aspiration and discipline—conditions familiar in many diaspora families, where achievement is treated as both possibility and obligation. Her early life included an education that leaned into the arts; she later earned a degree in fine arts, a detail that complicates any simplistic narrative about her as purely ideological. Politics is performance, yes, but it is also composition: the crafting of a public self. Love’s background helped her understand that craft.

She began her public service in Utah local politics, joining the Saratoga Springs City Council in 2003 and becoming mayor in 2009. The timing mattered: the Great Recession forced municipal leaders into hard choices about budgets and growth. Love built a reputation for fiscal conservatism and managerial competence—an identity that would become central to her national appeal.

In 2014, she made history by becoming the first Black person elected to represent Utah in Congress and the first Black Republican woman elected to the House. Her election was treated as a symbolic breakthrough, though Love herself often framed her politics as personal responsibility and opportunity rather than structural critique. That tension—between the symbolism others assigned her and the ideology she practiced—defined much of her career.

In Congress (2015–2019), she served on committees including Financial Services and positioned herself as a Republican voice sometimes critical of certain party rhetoric while still aligned with conservative policy preferences. The public’s fascination with her often reflected a broader American habit: treating Black political figures as evidence in arguments about race rather than as policymakers with specific agendas. Love had to navigate that projection constantly.

After losing reelection in 2018, she remained a public figure through media commentary and political roles. Her illness, disclosed later, reframed her public story, shifting the narrative from symbolic debate to mortality and family.

Love’s legacy will be argued over—by conservatives who see her as proof of ideological possibility, by critics who see her as a case study in the limits of representation without structural commitments. But history is rarely neat. Her biography captures the complexity of Black political identity in America: how “firsts” carry weight, how the burden of symbolism can distort the human story, and how a life can become larger than itself in the national imagination.

Clarence O. Smith: the strategist who helped build ESSENCE as an institution, not a trend

Clarence O. Smith understood something fundamental about power in America: representation is not only cultural; it is economic. When ESSENCE launched in 1970, it wasn’t merely a magazine—it was a counter-market, a proof of concept, a demand that advertisers and publishers recognize Black women as a central audience rather than a niche. Smith, one of ESSENCE’s four founders, died on April 21, 2025, at 92.

Smith was born in 1933, and his formative years unfolded in an America where Black ambition had to be engineered around exclusion. The civil rights movement opened doors, but it also clarified how many doors remained locked—especially in media and advertising. Smith’s early professional development took place in the world of communications and strategy, arenas where cultural narratives are converted into budgets and influence.

He began his public “performance”—again, meaning the act of addressing an audience—through institution-building. Founding ESSENCE required not only editorial vision but business courage: raising money, persuading advertisers, building distribution, convincing gatekeepers that Black women’s lives were not a niche story but a defining American story. Smith’s role is often described as strategic and communicative; in practice, that meant translating Black women’s worth into the language corporate America pretends to respect: market size, purchasing power, loyalty, longevity.

What ESSENCE became—an enduring cultural institution—owes to that translation. Smith helped define what the magazine itself later called the “Black women’s market,” a phrase that sounds clinical but carried radical implications: Black women are not an afterthought; they are a primary constituency. That concept influenced advertising, publishing, and the broader recognition of Black women as cultural drivers and economic leaders.

In remembrances, ESSENCE emphasized Smith’s commitment to uplifting Black women and his role in redefining media economics. That legacy matters beyond publishing. In a society where resources follow attention, building a platform that centers Black women is a form of civic work—expanding visibility, shaping policy conversations indirectly, creating pipelines for Black journalists and editors.

Smith’s death in 2025 is a reminder that activism is not only protest. Sometimes it is infrastructure: the creation of institutions durable enough to outlive the cycles of outrage. ESSENCE has been criticized at times, praised at others, but it has endured—and endurance itself can be political. Smith helped build that endurance, turning an editorial idea into an institution that permanently altered the American media landscape.

Alexis Herman: labor’s negotiator, civil rights’ organizer, and the Cabinet official who made power look like logistics

Alexis Herman’s career reads like a map of late-20th-century Democratic infrastructure: civil rights work, party organizing, executive governance, and the particular skill of making negotiations end before the country fractures. She died on April 25, 2025, at 77. Herman was the first Black U.S. Secretary of Labor, and her tenure included mediating the 1997 UPS strike—one of the largest labor actions in a decade.

Born in segregated Mobile, Alabama, Herman’s childhood was marked by racial violence and the clarity it produces: she understood early that the state can fail you, and that community networks become survival. Reporting has noted traumatic experiences in her early life, including the public realities of white supremacist intimidation. Those experiences did not turn her inward; they pushed her toward the machinery of change.

She began her public service young. Under President Jimmy Carter, she became director of the Labor Department’s Women’s Bureau at 29—an appointment that signaled both her talent and the era’s cautious opening of opportunity. From there, she moved through political and institutional roles that demanded stamina: organizing within the Democratic Party, building coalitions, doing the unglamorous work that makes elections and policy possible.

In the Clinton years, Herman’s influence became national. As Secretary of Labor (1997–2001), she operated at the intersection of business, workers, unions, and the federal state. Her role in resolving the UPS strike revealed her distinctive talent: treating conflict as solvable through structured negotiation rather than performance. She also worked on worker training initiatives and labor protections, and her tenure occurred during debates about globalization, wages, and the evolving nature of work.

Herman’s public image was often that of a polished insider, but that polish masked a deeper organizing sensibility. She was mentored by civil rights leaders, and her career carried the movement’s DNA into government: the belief that policy is the mechanism through which dignity becomes real. After leaving government, she continued work in corporate diversity and consulting, remaining a presence in civic and political networks.

Her legacy is also shaped by the fact that powerful Black women are frequently subject to scrutiny that blurs into suspicion. Herman faced ethics-related controversy during her career; she was cleared of wrongdoing, but the episode reflects a broader American pattern: the costs of proximity to power are often higher for Black women, whose ambition is more easily framed as illegitimate.

In the end, Herman’s story is a reminder that public service is often logistical heroism. She made negotiations work. She made systems move. She treated the dignity of workers as a governing priority—not a campaign phrase. And she modeled what Black authority can look like when it is competent enough to become unignorable.

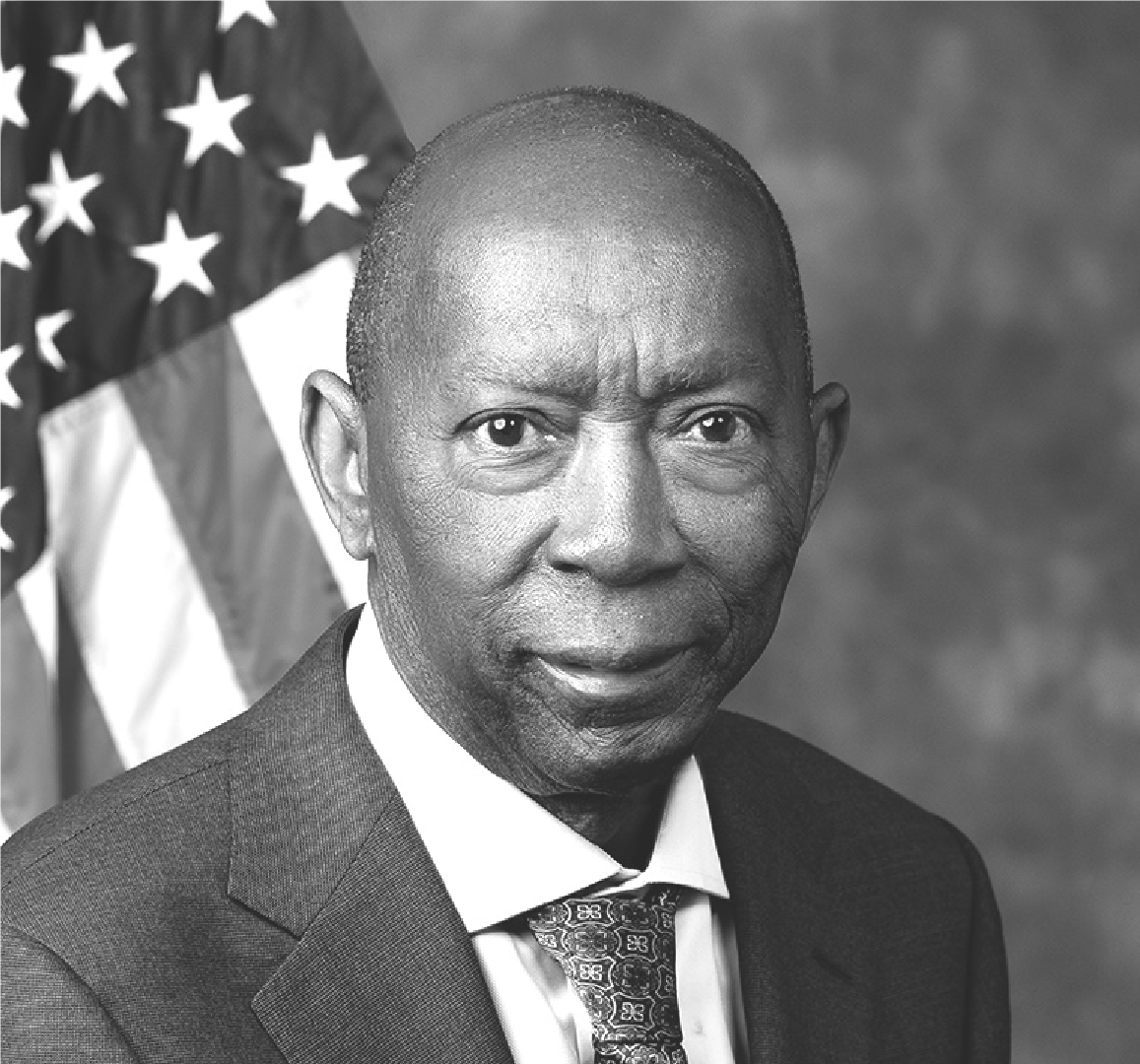

Charles Rangel: Harlem’s long-serving power broker, flawed, formidable, and historically central

Charles B. Rangel’s political career lasted so long it became weather: always there, shaping Harlem’s relationship to Washington, shaping the Congressional Black Caucus’s influence, shaping debates about taxes, foreign policy, and civil rights. He died on May 26, 2025. His life story—Harlem upbringing, Korean War service, rise to Congress—was repeatedly framed as American uplift, and not without reason. But Rangel’s legacy is also a study in complexity: moral ambition paired with ethical controversy, institutional clout paired with human fallibility.

Born in Harlem in 1930, Rangel came of age in a community that was both culturally rich and politically neglected. He dropped out of high school, served in the Army during the Korean War, and earned a Purple Heart—experiences that shaped his later persona: tough, direct, a man who spoke in a gravelly voice that sounded like the city itself. The war became a pivot point in the narrative he told about himself—discipline forged through danger, citizenship claimed through service.

He began his public career in New York politics and, in 1970, defeated Adam Clayton Powell Jr., another Harlem titan, to enter Congress. That win signaled both generational change and the relentless competitiveness of Harlem’s political life. Rangel’s tenure ultimately stretched for 46 years, making him one of the most enduring figures in modern Black electoral politics.

Rangel was a founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus and, in 2007, became the first Black chair of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee—a symbolic and practical achievement. He authored and supported legislation tied to civil rights and economic empowerment, and he was a vocal critic of the Iraq War. He also backed measures targeting apartheid-era South Africa, reflecting a tradition of Black internationalism in U.S. politics.

Then came the shadow: ethics violations that led to a formal censure in 2010. For supporters, the scandal was painful but not definitive; for critics, it became the headline. The truth is that Rangel’s career cannot be reduced to either triumph or disgrace. He was, for decades, a power broker whose office delivered tangible benefits to constituents—housing advocacy, funding streams, influence that Harlem used. He also embodied the hazards of entrenched power: the temptation to treat rules as optional when you believe your mission is righteous.

Rangel’s memoir title—And I Haven’t Had a Bad Day Since—captures the audacity of his self-mythology. But myth-making is a political skill: it organizes a life into something teachable. Rangel taught multiple lessons at once: that Black political power can be accumulated and used; that representation can produce material results; that personal discipline can rewrite a life story; and that accountability still matters, even for the historically significant.

In the wake of his death, Harlem’s relationship to him will remain complicated and intimate. He was not merely a politician from Harlem. For nearly half a century, he was Harlem’s voice inside the federal state—an imperfect instrument, but a consequential one.

Assata Shakur: An activist whose death reopened an old national argument

The arc of Assata Shakur’s life was bold and unapologetic: a heroine within Black communities who see beyond the thin veil of deceptive allegations, justly regarding her as a symbol of Black resistance and the country’s unresolved legacy. In September 2025, she died in Havana, Cube at 78, according to authorities and multiple major news organizations. Her death did not settle the argument; it intensified it, because Shakur’s story sits exactly where American history remains most disputed: the meanings of violence, the boundaries of state authority, the ethics of resistance.

Born JoAnne Deborah Byron in New York City in 1947, Shakur’s childhood included time in both the North and the South, a biographical detail that matters because it reflects the era’s racial geography: the particular ways Black identity is shaped by region, by migration, by the daily negotiations of dignity. Her early life, by most accounts, was marked by restlessness and search—an emotional preparation for the political intensity that would come later.

She began her public political “performance” as an activist during the late 1960s and early 1970s, a period when Black liberation politics fragmented into multiple organizational forms: the Black Panther Party, community programs, armed self-defense factions, and a broader movement ecology responding to policing, poverty, and state repression. Shakur’s involvement with the Panthers was brief; she later became associated with the Black Liberation Army, an affiliation that would define how law enforcement and the media framed her for decades.

The central event that shaped her public identity occurred in 1973 on the New Jersey Turnpike: a traffic stop and a shootout that left a state trooper dead, another wounded, and a fellow activist dead. Shakur was wounded as well. In 1977, she was convicted of first-degree murder and related charges, then sentenced to life in prison. She maintained her innocence, arguing she could not have fired the shots; her case became emblematic for supporters who saw it as politically charged.

In 1979, she escaped from prison with help from other activists and eventually resurfaced in Cuba, where she was granted asylum in 1984. The U.S. government sought her extradition for decades, and in 2013 the FBI added her to its Most Wanted Terrorists list, offering a large reward. Meanwhile, in activist and cultural circles—especially hip-hop—Shakur became a symbol of resistance and a reference point in the language of Black radical politics.

Shakur also authored a memoir, Assata: An Autobiography, which shaped her narrative in her own voice. The book’s existence matters: it is part of how Shakur remained present despite exile, insisting on interpretation rather than surrendering her story to the state.

Her death in 2025 revived unresolved questions: What does justice look like when political conflict and criminal law overlap? Who gets to define legitimacy? How do movements remember figures whose lives include both courage and harm? Shakur’s life—and now her death—forces a confrontation with the fact that America’s moral arguments do not end neatly. They persist, passing from courts to streets to memory, where the verdict is rarely unanimous.

Viola Ford Fletcher: the Tulsa survivor who turned memory into testimony

Viola Ford Fletcher lived long enough to see America attempt, again and again, to bury the story she survived. She refused. Fletcher—known widely as “Mother Fletcher,” one of the last known survivors of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre—died on November 24, 2025, at 111. The death itself was news, but the life was the headline: a century-spanning biography that turned personal memory into public demand.

She was born Viola Ford on May 10, 1914, in Oklahoma. Her childhood was marked by the ordinary hopes of Black families who believed in work, education, and community—hopes that would be violently disrupted when she was seven. In 1921, she lived through the destruction of Tulsa’s Greenwood District, often called “Black Wall Street,” when a white mob attacked, burning homes and businesses and killing residents. The massacre was not just violence; it was theft—of property, of stability, of intergenerational wealth. Fletcher carried that theft in her body and memory for more than a century.

Her “public performance,” in the most meaningful sense, arrived late. For decades, survivors were not treated as witnesses but as inconveniences to a city invested in forgetting. Fletcher lived her life—work, family, migration—while the nation largely ignored what happened. But as public interest in Tulsa’s history resurfaced, Fletcher became a central voice, not because she sought fame, but because she understood the stakes of silence.

In 2021—one hundred years after the massacre—she testified before Congress, describing what she saw and what was taken, and calling for reparations and accountability. The testimony was remarkable not only for its content but for its existence: a Black elder insisting that the country acknowledge a crime it had tried to erase. Public testimony, especially from Black elders, functions as a kind of civic ritual: it converts private grief into public obligation.

After her testimony, Fletcher became a symbol of both survival and unfinished justice. Her story circulated widely, and she co-authored a memoir that reinforced her primary message: do not let them bury the story. That phrase reads like both warning and mission statement.

Fletcher’s legacy is, in a sense, America’s moral homework. She forced the country to confront the fact that time does not erase debt. Her life shows how historical violence becomes present-day inequality—not abstractly, but through property loss, educational disruption, and the generational consequences of terror. She died having turned memory into testimony, testimony into public record, and public record into a demand that still waits for fulfillment.

If activism is often imagined as youthful protest, Fletcher’s life insists on a broader definition: activism as survival long enough to tell the truth, then telling it anyway.

Jamil Al-Amin: the militant orator who became an imam—and whose death in custody revived old questions about state power

Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin lived multiple public lives, each fully enough to generate its own mythology—and consequential enough to refuse any neat moral conclusion. In the 1960s, as H. Rap Brown, he rose to national prominence as a firebrand organizer and the fifth chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), inheriting the role as the movement’s center of gravity shifted from integrationist appeal toward Black Power insistence. Later, after prison and conversion, he reemerged in Atlanta as a Muslim community leader—an imam whose authority came not from cameras but from proximity: funerals, counsel, neighborhood disputes, the slow work of trying to keep young men alive. In the end, he became, once again, a symbol contested by the country’s deepest fault lines: convicted murderer to prosecutors and police, political prisoner to supporters, enduring cautionary tale to others. Al-Amin died on November 23, 2025, at Federal Medical Center Butner in North Carolina, at 82, while serving a life sentence.

He was born Hubert Gerold Brown on October 4, 1943, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, a birthplace that matters because the South did not merely supply the movement with grievance; it supplied it with training. The Jim Crow order demanded early political literacy from Black children—lessons absorbed through family stories, street rules, and the daily choreography of insult and endurance. Brown’s early years, by most accounts, were marked by volatility and brilliance: the kind of intelligence that finds attention quickly, the kind of anger that can become either self-destruction or organizing fuel. He began “performing” publicly as a speaker—before he became famous as a writer or organizational head, he became known as an orator, the kind who could turn a crowd into a single breathing organism.

In 1967, SNCC named him chairman after Stokely Carmichael, and Brown stepped into leadership at a moment when the movement’s internal debates—nonviolence versus self-defense, interracial coalition versus Black autonomy—were becoming impossible to keep politely theoretical. Brown’s rhetoric was incendiary, but it was also diagnostic. He spoke about police violence and white supremacy with the tone of someone describing weather: not shocking, simply present. That posture—refusing to beg for recognition—made him a hero to some and a target to others. Press coverage and government attention followed. His name became entangled in the politics of public order, including accusations tied to unrest after speeches, and his profile placed him squarely in the state’s counter-movement machinery. The Washington Post+2AP News+2

Brown also authored Die Nigger Die! (1969), a title that still lands like a slap because it was designed to: a rhetorical trap that forces the reader to confront the violence embedded in American life and language. The work functioned as political autobiography and movement document—part sermon, part indictment, part attempt to tell the story from inside the storm. For supporters, it remains evidence of his historical significance; for critics, it remains proof of extremism. The truth is more complicated: Brown was part of a generation that believed polite language had already failed Black people. Their question was not whether America was violent—but whether Black people were permitted to name that violence out loud.

The later chapters of Al-Amin’s life are inseparable from prison and from Islam. Reporting widely notes that after earlier incarceration in the 1970s, he converted and eventually took the name Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin, becoming a religious leader with deep community ties in Atlanta. By then, the public “performance” shifted: less podium, more pastoral authority. He built credibility through service rather than spectacle. To many in Atlanta’s West End, he was not a relic of the ’60s; he was the local imam who showed up.

Then came the event that would permanently lock his biography into America’s conflict over law and politics. In 2000, a Fulton County deputy sheriff, Ricky Kinchen, was killed and another deputy wounded in a shooting during an attempted arrest. Al-Amin was convicted in 2002 and sentenced to life. Prosecutors framed the case as direct, evidence-driven justice; Al-Amin’s family and supporters argued he was framed and that the trial reflected a longer history of state targeting of Black radicals. Major reporting on his death has consistently included both the legal record and the persistence of doubt among advocates—a duality that never resolved into consensus, yet the country’s insatiable appetite of pursuit and assassination of Black-impact voices, and the evidence of such, will forever cast doubt upon any allegation and sentence.

By the 2010s, Al-Amin’s health declined; his widow and others described serious illness, including cancer, and he spent years in federal medical custody. His death in November 2025 triggered a familiar second argument—medical neglect versus inevitability—because Al-Amin’s supporters interpreted the conditions of his incarceration as part of a broader pattern of punitive control. Mainstream obituaries emphasized his movement prominence, his later religious leadership, and the facts of his conviction and imprisonment.

What, then, is the honest way to memorialize a life like this—one that contains organizing brilliance and moral abrasiveness, community service and a homicide conviction, reverence and rage? The only responsible answer is to refuse simplification. Al-Amin’s legacy is not a slogan; it is an archive of America’s unresolved disputes: how the state responds to radical Black politics; how movements handle figures who attracted both admiration and fear; how communities reconcile pastoral leadership with criminal accusation; how truth is contested when the stakes are existential. In death, as in life, he remains what he always was: a figure who forces the country to reveal its assumptions about legitimacy—who gets it, who loses it, and who never had it to begin with.

What Comes Next

This Activism and Public Service edition is the second installment in KOLUMN Magazine’s 2025 remembrance series. The final edition—Sports—will document the athletes, coaches, and sports figures lost in 2025 whose careers reshaped competition, representation, and community pride.