KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

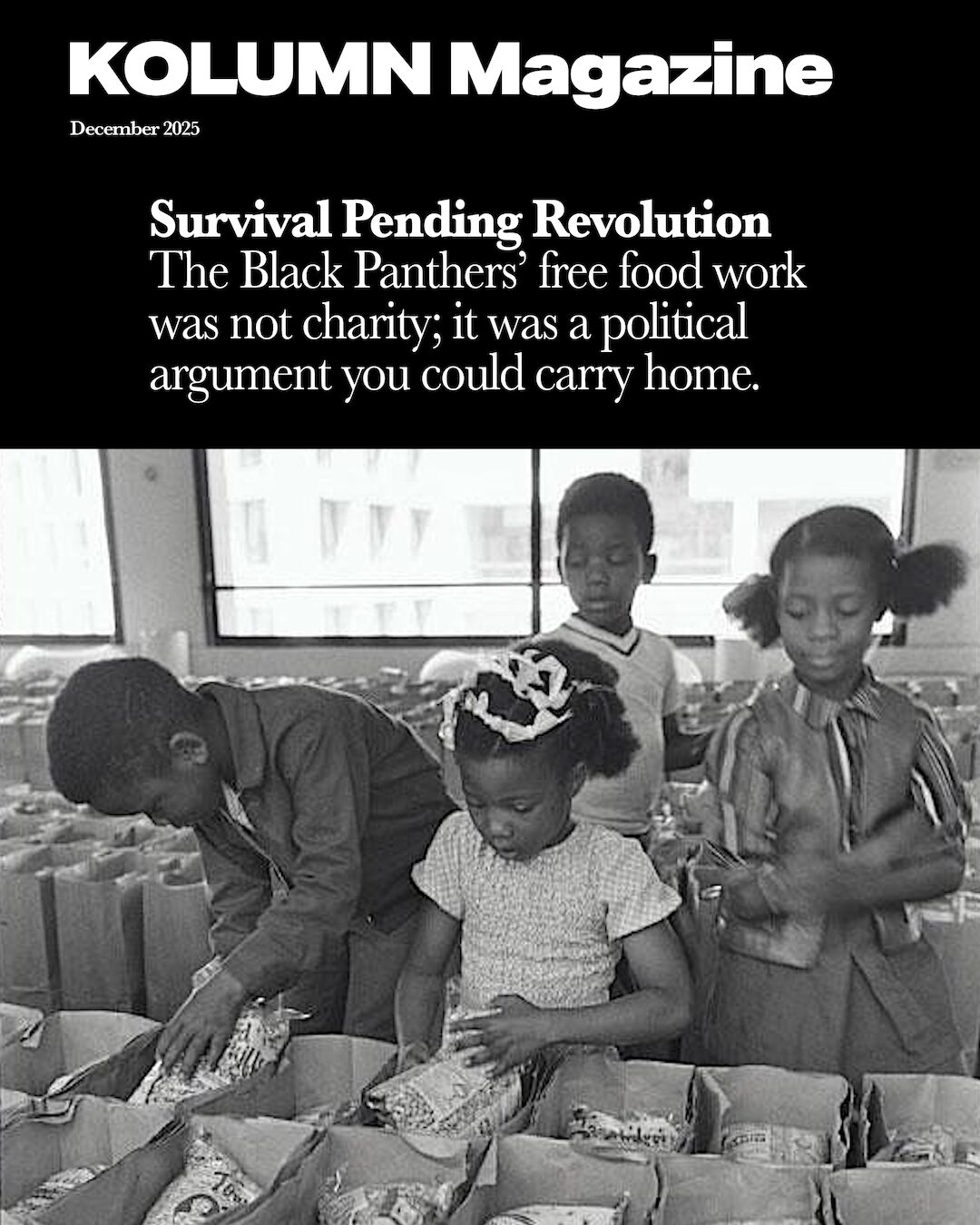

On a winter morning in the early 1970s, a line forms in the cold with the quiet discipline of people who have done this before—people who know what it means to stretch a week’s food into something that resembles a month, to turn a season into a math problem. Inside a borrowed kitchen—often a church, sometimes a community center—volunteers move quickly, not because they are frantic, but because the work is timed: the eggs must be cooked before school starts; the bags must be packed before parents leave for shifts that begin at sunrise; the distribution must finish before the police decide to pay a visit. In the background, there is the paper sound of grocery sacks opening and being filled, the blunt percussion of canned goods meeting the bottom of a bag.

This is not the popular image of the Black Panther Party. America’s memory prefers the Panthers as silhouette: black beret, leather jacket, rifle held upright like punctuation. That picture—useful to Hollywood, useful to politicians, useful to law enforcement—flattens the Party into a posture. But in city after city, through much of the 1970s, the Panthers were also a schedule, a menu, a supply chain. Their “Survival Programs,” as the Party called them, operated with a kind of municipal ambition: feeding children before school, distributing groceries to families, offering health services, transportation, and education—in short, building the practical scaffolding of life where poverty and policy had left gaps wide enough to fall through.

During the winter season, those gaps widened. The season arrives with its double message—abundance as a public performance, scarcity as a private fact. In Black neighborhoods facing unemployment, inflation, and rising costs of food, December didn’t just heighten need; it made it visible. So the Panthers did what organizers do: they made the season into an operation. They mobilized donations, they held food distributions, they leaned on merchants and allies, they printed calls to action, and they turned “giving” into an argument about who was responsible for survival in America.

To understand how the Black Panther Party organized winter donations through their People’s Free Food Programs, you have to see the Party as it often saw itself in that decade: not merely as a protest movement but as a counter-institution—a structure built to prove, in real time, that communities could meet their own needs and, in doing so, expose the state’s failure to meet them. That the work looked like charity was, to the Panthers, part of the point: when the government abdicates, feeding people becomes political—because it forces the question of why they were hungry in the first place.

“Survival Pending Revolution”: the Panthers’ governing idea

The phrase that hangs over the Panthers’ social-service work—Survival Pending Revolution—was not a slogan designed for the soft edge of public relations. It was a diagnosis. The Panthers believed Black communities were being economically strangled: by underemployment, by discriminatory housing, by poor schools, by health disparities, by policing as a form of social control. Their Ten-Point Program demanded jobs, housing, education, and an end to police brutality; but the Party recognized that a platform, on its own, does not feed a child at 7:15 a.m.

The Free Breakfast for Children Program—launched in 1969, then expanded widely—became the most famous of these efforts, and its success helped anchor the Party’s broader “survival” portfolio in the public imagination. It also taught the Panthers something crucial: that the most radical work could look, from the outside, like the most ordinary act—feeding children before school.

By the 1970s, that logic broadened. If breakfast could be a wedge into the daily life of a community—if it could pull volunteers in, build credibility, and place the Party in the role of dependable provider—then other needs could be met the same way. Free food became not just a meal, but a method.

In the historical record, the Panthers’ food programs appear in multiple forms and names: the Free Breakfast Program; free grocery distributions; survival rallies; “Survival Day” events; and the People’s Free Food Program, which—depending on chapter and period—refers to organized grocery bag distributions that were explicitly part of the Survival Programs infrastructure. Scholars and museum historians have emphasized that these programs were local, flexible, and often led by women who handled the demanding labor of procurement, preparation, and distribution.

A key point gets lost when these programs are described as “community service,” a phrase that can shrink political ambition into a kind of volunteerism. The Panthers were not simply filling a gap; they were dramatizing the existence of the gap. Their social programs were a critique in action: this is what we can do, right now, with the people—so what does it say about the state that we have to do it at all?

The People’s Free Food Programs: a grocery bag as political unit

A free breakfast is intimate: a child, a plate, a morning routine. Free food distribution, by contrast, is infrastructural. It requires storage. It requires transportation. It requires a flow of goods that doesn’t break under pressure.

The Panthers built that flow in the only way most under-resourced organizations can: through relationships and leverage. Food came from individual donors, sympathetic merchants, churches, and community allies. It also came—sometimes—through pressure campaigns that highlighted a business’s dependence on Black customers. The Party’s ability to mobilize boycotts, or simply to threaten public accountability, could be enough to pry open a backroom supply of eggs, bread, or produce that would otherwise never reach a Panther pantry.

If this sounds like the language of modern mutual aid, it should. The Panthers were building what we would now call a community-based distribution network, with an ideology attached. They did not hide the politics. The program itself was a form of political education: not always a lecture, but a lived lesson in collective responsibility.

In the early 1970s, Panthers in multiple cities organized large-scale grocery distributions—sometimes at rallies or “Survival Conferences”—that handed out hundreds or thousands of bags of groceries in a single day. One scholarly treatment of the Panthers’ food politics notes grocery-bag distribution figures in the thousands across cities, emphasizing how these events scaled beyond a single neighborhood kitchen into something closer to a mass logistics exercise.

And that scaling mattered, because scale is where credibility lives. A few dozen grocery bags can be dismissed as symbolic. Thousands of bags force a question: how is this being done—and why isn’t the city doing it?

Why the season mattered: need, visibility, and narrative

Winter celebrations is a story Americans tell about themselves. It is a national narrative of generosity—and, therefore, a national stage for hypocrisy.

For poor families, the season often arrives as a bright pressure. Food costs rise. Children’s expectations, fed by advertising, rise too. Bills do not pause. And in the 1970s—an era marked by inflation and economic shifts that hit working-class communities hard—seasonal need could become acute. The Panthers understood that the season offered both a practical reason to organize and a symbolic opportunity to reframe what “giving” was supposed to mean.

A winter-oriented food drive could accomplish several things at once:

Meet immediate needs (seasonal meals, pantry staples, groceries).

Recruit volunteers who may not join a political organization but will help pack bags.

Build alliances with churches, civic groups, and merchants in a culturally resonant season.

Win public legitimacy—the kind that scares authorities precisely because it makes repression harder to justify.

The last point is not theoretical. The Free Breakfast Program, the most visible of the Panthers’ food efforts, drew intense attention from law enforcement agencies that recognized the political power of material service. Journalistic and historical accounts have noted how the Panthers’ breakfast work became a target for harassment and raids, precisely because it generated favorable publicity and deep community ties.

If breakfast could be framed as a “threat,” then a winter food drive—public, crowded, emotionally resonant—was doubly potent.

How a Panther winter drive worked: the mechanics of “Serve the People”

The specifics varied by chapter, but the Panthers’ winter donation work followed a recognizable organizing logic—one that modern nonprofit operators would find familiar, even if the Panthers’ political edge was sharper.

1) The ask: donations as a community referendum

The Panthers’ appeals were often simple and direct: donate food, donate toys, donate money, volunteer time. But embedded in the ask was a referendum on the local economy: businesses that profited from Black neighborhoods were being invited—or pressured—to demonstrate reciprocity.

The Party’s credibility came from consistency. In cities where Panthers had already been serving breakfasts or running other survival programs, a seasonal drive could lean on established trust. A donor wasn’t being asked to fund an idea; they were asked to supply an operation that already existed.

2) The site: churches, community centers, and borrowed infrastructure

Many Panther food programs were housed in churches or community spaces—places with kitchens, storage potential, and a kind of moral insulation. The symbolism mattered: a church basement repurposed into a political kitchen blurred the boundary between spiritual duty and social provision. Accounts of the Panthers’ breakfast efforts repeatedly underscore the use of church sites, especially early in the program’s expansion.

During the winter that church infrastructure could be particularly valuable, because churches were already engaged in seasonal charity. The Panthers, in effect, plugged their survival logistics into an existing cultural circuit of seasonal giving—then insisted that the giving be understood as justice, not benevolence.

3) The labor: women, discipline, and unglamorous excellence

The unromantic truth of food distribution is that it is exhausting. It requires early mornings, heavy lifting, repetitive tasks, cleanup, and constant improvisation when supply falls short.

Multiple historical treatments emphasize women’s central role in Panther survival programs and the day-to-day operational labor of feeding people. Photographic histories and contemporary reflections highlight women preparing food bags, organizing distribution, and running program sites—work that rarely makes it into the simplified legend of the Party.

During winter, that labor multiplied. More families came. More children came. Expectations were higher. The Panthers’ credibility depended on being ready.

4) The distribution: “Survival Day,” grocery bags, and public proof

Seasonal distributions were not merely handoffs; they were events. A line itself can become a form of testimony: visible proof of need, visible proof of response.

One scholarly account of Panther food work describes large public events launching or expanding local Free Food Programs, where thousands of grocery bags were distributed across multiple cities in 1972 alone—suggesting an intentional strategy of public scale and replication.

That replication was crucial. A winter drive in one city was not only about that city; it was evidence that a model could travel. That, too, was political.

The Panthers and the politics of being loved

There is a detail that repeats across reminiscences of Panther survival programs: the tenderness of ordinary care. People recall the early hours, the smell of food, the insistence on dignity. In some accounts, former Panthers describe the programs as “showing love for our people,” language that might sound sentimental until you consider how radical love becomes in a society organized around deprivation.

Winter, in that sense, was an amplifier. If the Panthers could position themselves as the people who ensured children ate and families had groceries during the most symbolically “family” season of the year, then they were not merely providing food; they were contesting the emotional economy of the season—who deserved to feel secure, who deserved to feel celebrated.

This is where the Panthers’ winter donation work becomes particularly revealing. It shows the Party operating not only as a political organization but as a cultural competitor to the state and the marketplace. Where the marketplace sold joy and the state rationed assistance, the Panthers tried to deliver material support as a right—wrapped, yes, in the seasonal language of giving, but anchored in a theory of collective responsibility.

Repression’s shadow: why feeding people invited police attention

It is tempting to treat the Panthers’ food programs as the “nice” side of the movement—a corrective to the gun-and-beret stereotype. But that framing misses the conflict at the center of the story: the Panthers’ care work was controversial not despite its softness, but because of its effectiveness.

Authorities understood that service built legitimacy. A breakfast program that fed thousands of children did something that speeches could not: it made the Panthers dependable. That dependability threatened the political order because it shifted allegiance away from official institutions. Press accounts and historical summaries repeatedly note law enforcement harassment and raids aimed at disrupting Panther food programs and undermining the Party’s community standing.

During winter, the optics of repression could be especially volatile. A raid on a pantry is one thing; a raid in the vicinity of children and families waiting for seasonal groceries is another. Even when pressure was applied indirectly—through surveillance, intimidation, or public smear campaigns—the effect was to raise the costs of care.

And yet the programs persisted across much of the decade, adapting to local conditions and shifting Party strategy. That persistence is part of what makes the Panthers’ seasonal work worth revisiting now: it demonstrates that survival programs were not side projects; they were central to how the Panthers imagined power.

The longer legacy: from Panther breakfasts to public policy—without the politics

A familiar story is often told about the Panthers’ breakfast program: that it helped inspire or accelerate government adoption of school breakfast efforts. That story is broadly supported across mainstream historical accounts and contemporary journalism that notes how the Panthers’ feeding programs exposed need and pressured institutions to respond.

But the sharper version of the story is this: the state can adopt the form of a radical program while stripping its critique.

A school breakfast served by a federal or district program is still breakfast—and for families, the distinction may not matter in the morning rush. But the Panthers’ program was not only a meal; it was a political education about why hunger existed and who benefitted from it. When the state scales the service but erases the analysis, it neutralizes the threat while preserving the appearance of progress.

That dynamic is not unique to the Panthers. It is, arguably, the American pattern: absorb the tactic, reject the ideology, and declare the problem solved.

What a Panther winter tells us now

In 2025, the phrase “mutual aid” has become familiar, often invoked during crises when official systems fail. But the Panthers were practicing mutual aid with a specific insistence: that it was not an emergency substitute for politics—it was politics.

Their winter donation work through the People’s Free Food Programs throughout the 1970s offers a case study in how care becomes strategy:

Care as recruitment: people join a movement when it touches their lives.

Care as legitimacy: a movement becomes dangerous when it becomes trusted.

Care as counter-government: when you feed people, you also teach them what they have been denied.

This is why the Panthers’ seasonal work endures in the cultural memory, even when the details fade. It wasn’t merely that they gave people food. Plenty of organizations did that. It was that they treated food as a measure of political failure—and as a platform for building a different kind of civic order, one grocery bag at a time.

And perhaps that is the most uncomfortable lesson of the Panthers’ winter baskets: they remind us that hunger is never just hunger. It is policy. It is economy. It is the distribution of dignity.

The Panthers understood that winter—the nation’s favorite story about generosity—could be turned into a story about accountability. They made the season not only warmer, but clearer. They forced a question into the season’s glow:

If a grassroots organization with limited resources could organize the food, the volunteers, the sites, and the distribution—what, exactly, was the government doing?