By KOLUMN Magazine

We lived in a small two-bedroom house on a dead-end street, the kind of street that felt like a sentence with a period at the end. Cars didn’t wander in for no reason. People came because they meant to—because they knew somebody there, because they had something to drop off, because they were the kind of neighbor who believed checking in was a form of insurance. When you live on a dead-end, the world feels a half-step quieter, like you’ve been given a small mercy: fewer strangers passing, fewer reasons to look over your shoulder.

But quiet didn’t mean easy. Quiet didn’t mean soft. Quiet meant you could hear the real things—the furnace droning, the television murmuring, my mother’s keys in the lock at an hour that told you exactly how much of her day had been spent serving somebody else’s needs.

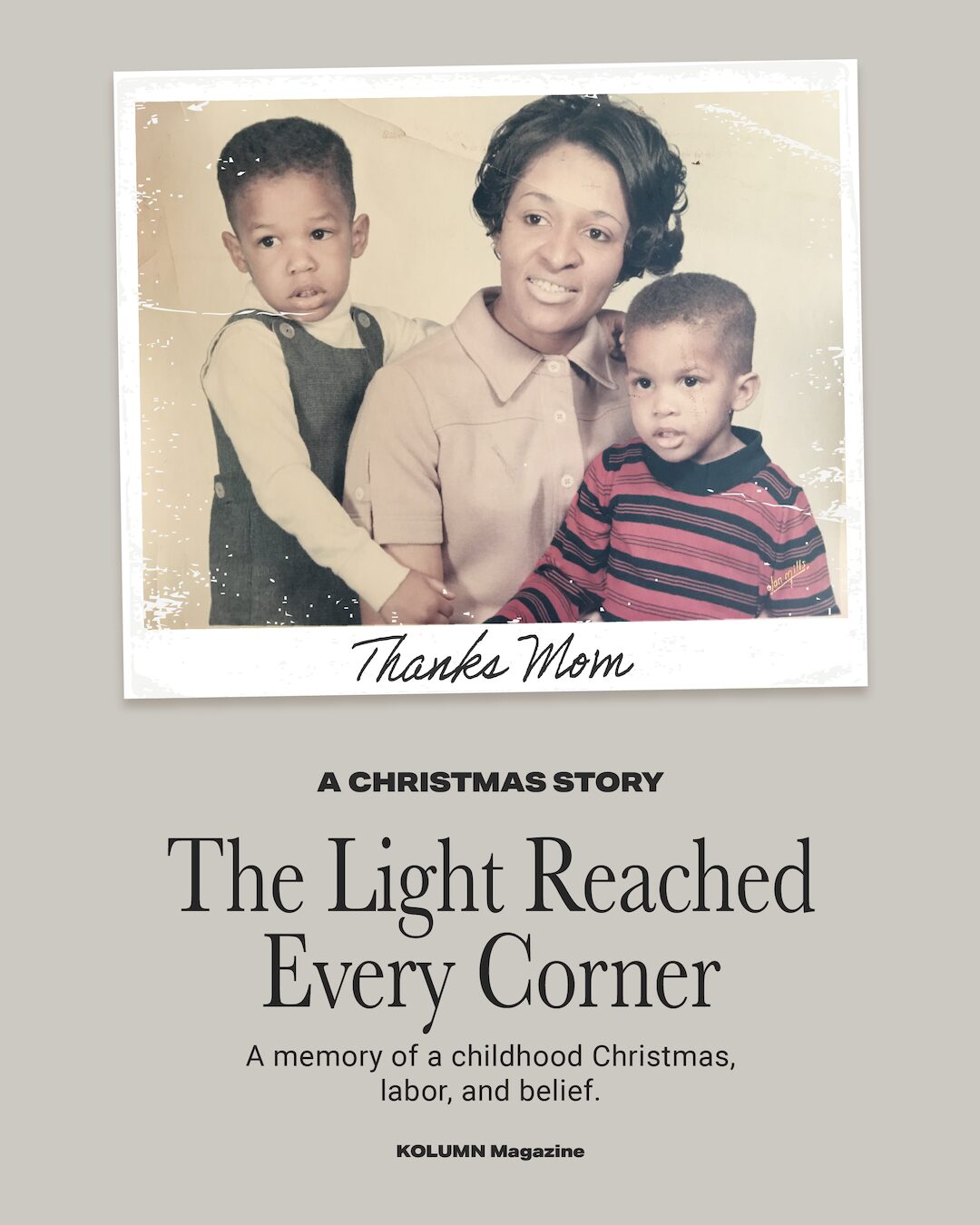

In the 1970s, that house held my mother, my brother, and me. It held winter. It held work. And every December, without fail, it held Christmas—though “held” isn’t quite the right verb. Christmas didn’t simply sit in our house like a guest. It was something my mother made there, like a set built overnight, like a stage dressed in secrecy.

I remember our living room first—not because it was large, but because it was deliberate. The living room was where rules lived. It was where joy showed up. It was where the air changed, where a normal day could be re-lit into something ceremonial.

On Christmas, we had a tinsel Christmas tree—silver and defiant, catching light the way only tinsel can, each strand bending brightness into something theatrical. The tree was never shy. It was a signal. You didn’t have to be religious to feel it: something is coming. Something has already been planned.

And then there was the fan.

We had a Christmas holiday fan in the living room that turned slowly, occupying every corner of the room in warm red, blue and green light with each turn. It didn’t blink or twinkle like string lights. It swept. Color traveled across the walls, slid over the couch, passed over the floor like a hand smoothing a bedsheet. The fan made the room feel larger than it was. Even the corners—those forgotten places where dust gathers and toys hide—took their turn glowing.

The fan wasn’t just decoration. It was atmosphere. It made our small living room feel like it had depth, like the house expanded into light.

But before the morning, there was always the perimeter.

My mother would place chairs at the outer border of the living room to avoid us being tempted from peeking. Chair by chair, she created a ring—simple, effective, nonnegotiable. We didn’t have a basement to be banished to or a spare room where secrets could wait. We had a living room that had to do everything: family room, playroom, occasional folding station, the place where you could sit and think when the kitchen felt too loud. So my mother turned furniture into a boundary and called it discipline.

Those chairs did more than block our footsteps. They blocked our imagination from running ahead of her capacity. They said: wait. They said: not yet. They said: you will not steal your own wonder.

Looking back now, I understand the chairs were also strategy. My mother worked two jobs, often into the late hour of the day. She needed time protected from little-boy curiosity, time to arrange the morning she wanted us to have. In our house, magic had to be scheduled.

Christmas Eve belonged to waiting

Every Christmas Eve, my brother and I would spend most of the evening at my family-adopted grandmother’s house, the Parkers. “Adopted” the way Black families use the word when love has already done the paperwork. Not blood, but belonging. Not ancestry, but arrival. The Parkers were family because they acted like it—year after year, holiday after holiday, on the nights when a working mother needed an ally.

Their home had a particular kind of warmth, not only temperature but tone. Adults spoke in half-sentences—the kind of talk that is really a ledger: who’s working, who’s struggling, who’s coming by, who needs help, who just bought a new coat, who is sick and pretending not to be. There were smells that suggested somebody had started cooking before we got there, and the sounds of a television special playing to fill the quiet.

My brother and I understood—even if we couldn’t have explained it—that being there was part of a system. My mother’s two jobs were not a slogan. They were mortgage, tuition, uniforms, groceries, bills. Because my brother and I attended a small private school, St. Mary’s Academy (West), with approximately 100 other Black students, our household wasn’t only paying for life; it was paying for possibility.

And then, before we fell asleep on Christmas Eve, my brother and I would share talk about what could possibly sit beneath the Christmas tree.

We whispered like we were conducting a serious investigation. Hot Wheels cars felt plausible. Superhero action figures—maybe, if the year had been kind. Comic books, hopefully. We named the popular toys of the 1970s the way other children named saints. We traded probabilities like little economists, balancing desire against the knowledge that our mother worked too hard for us to pretend money wasn’t real.

Outside, the Christmas holiday weather was often cold. Norfolk winters aren’t always the snow-globe kind of cold people imagine in northern movies, but they can be sharp and damp, the kind that climbs into your sleeves and settles in your bones. Cold changes the scale of a holiday. It makes indoor light feel earned. It turns a living room into a refuge.

At some point, my mother would arrive to pick us up. Not early. Not conveniently. After work. After the late hours. At an hour that felt like the day had already spent itself.

She would take us home.

And here is the part I still don’t fully understand how she pulled off:

My mother would arrive home, without us knowing, to prepare Christmas for us.

Not “without us watching.” Without us knowing. The secrecy was part of the gift. The transformation occurred outside our awareness, and that made it feel supernatural. It’s one thing to wrap gifts. It’s another thing to make a small house look transformed without letting the children witness the transformation, to preserve surprise in a place where sound travels through thin walls.

The chairs helped. The perimeter trained our bodies to stay back. But the deeper truth is that she trained our hearts. She made anticipation safe.

Midnight Mass: The hour where the day turns

Some Christmas Eves, my mother, my brother, and I would attend midnight Mass at St. Mary’s, a Black Catholic parish in downtown Norfolk, Virginia. We were Catholic, and that mattered. It mattered because it gave the holiday a second spine: not only gifts and toys, not only school parties and neighborhood lights, but a sacred hour where the night became a threshold.

If you didn’t grow up Catholic, it’s hard to explain the atmosphere of that hour. The Church can be quiet in a way that feels like weight. Even a modest parish becomes ceremonial at midnight. People arrive in coats, carrying the cold on their shoulders, and the building gathers their breath and turns it into warmth. The liturgy moves like a river you can’t stop—stand, sit, kneel—old language and familiar responses that make time feel structured, contained.

I was always aware that I was a child awake at an adult hour, participating in something serious.

Only later did I learn that the broader Black Catholic world was also in motion in those same years. In 1968, the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus issued a statement declaring that the Catholic Church in the United States was “primarily a white, racist institution,” a sentence that still lands like a gavel because it said out loud what many had experienced quietly.

In the early 1970s, Black Catholics were building institutions and networks to advocate, to worship more fully as themselves, and to push the Church toward accountability. The National Office for Black Catholics, founded in 1970, emerged as an umbrella organization intended to be a voice and a vehicle for Black Catholic priorities in that era.

I didn’t know those names when I was small. What I knew was this: my mother wanted us in church at the hour when everyone else was sleeping, as if she believed the world could be remade in darkness, quietly, through ritual. I also knew—because children are sensitive to fatigue—that it cost her something to be there. She was tired. And she showed up anyway.

Midnight Mass did not replace the toys we wanted. It framed them. It reminded us that Christmas belonged to something larger than a shopping list, even if our shopping list mattered deeply to us.

School in December: The month-long rehearsal

In school, December didn’t arrive as a date. It arrived as a mood.

Our schoolmates spent the month planning for the Christmas holiday the way children always plan for something too big to hold privately. They made lists. They compared rumors. They talked about what they thought their parents might buy, what they hoped would show up, what they were afraid might not.

In school we made Christmas ornaments and hand-made garland. Construction paper dulled the scissors. Glue dried in streaks. Glitter traveled onto skin and refused to leave. The classroom became a workshop. The teacher became a kind of foreman of cheer, allowing just enough chaos for children to feel like creators.

In school we exchanged gifts with friends. Those gifts were rarely expensive. They didn’t need to be. In a school that small, gift exchange was less about the object and more about proof: I see you. You matter. We are connected beyond grades and recess.

Those classroom rituals did something important for kids like us. They democratized the holiday. Even if home life was tight, school could produce evidence that Christmas was coming. An ornament could hang anywhere. A paper garland could transform a doorway. A small gift could make a child feel chosen.

Then I’d go home to a house where my mother’s labor would decide what was possible.

Norfolk, Black neighborhoods, and the shape of a “small” life

People like to tell stories about the 1970s as if it was simpler. I hear it all the time: simpler, slower, safer. Maybe it was simpler for somebody. For many Black families in cities like Norfolk, “simple” often meant “tight.” Tight budgets. Tight schedules. Tight homes. Tight systems of care built from relatives, adopted relatives, and neighbors who understood what it cost to keep children upright.

Norfolk’s neighborhood history—like the history of many American cities—was shaped by policy decisions that rarely used the word “race” out loud but built race into the blueprint. Long before the 1970s, redlining maps helped formalize patterns of segregation and disinvestment. The University of Richmond’s “Mapping Inequality” project includes a 1940 HOLC redlining map for Greater Norfolk and explains how these maps reflected and reinforced discriminatory housing practices.

And then there was “urban renewal,” a phrase that sounds clean until you learn what it meant on the ground. In Norfolk, redevelopment projects and clearance campaigns altered neighborhoods and displaced residents—often Black American residents—reshaping the city’s social geography. Encyclopedia Virginia’s overview of urban renewal in Norfolk describes how such projects transformed areas like East Ghent and contributed to demographic shifts tied to displacement.

I’m not claiming that I understood any of this as a child. I’m saying that the city carries its history in the way it feels to live there. You can sense the difference between a place that is allowed to flourish and a place that has to fight for maintenance. You can sense it in street repairs, in store density, in the way city attention arrives late—if it arrives at all.

So when I think about our dead-end street, I see it as both refuge and constraint. The street felt protective, quiet. The house felt small but ours. But the world outside the living room was shaped by forces larger than our family.

Christmas didn’t erase those forces. It pushed back against them, one carefully arranged morning at a time.

Toy culture: Why Hot Wheels felt like belonging

When I say we wanted Hot Wheels cars, I’m not talking about a niche desire. I’m talking about the mainstream language of childhood.

Hot Wheels were introduced in 1968, and part of their impact was design: low-friction “racing” wheels that made toy cars feel fast and thrilling in a child’s hand, and a collectability that turned play into pursuit. The Smithsonian has noted that the low-friction racing wheels created excitement for playing with—and collecting—fast-moving cars.

The Strong National Museum of Play describes how kids coveted the first “Sweet 16” muscle models released in 1968, as well as the candy colors of Spectraflame paint and the flexible plastic tracks that became part of the Hot Wheels ecosystem.

I didn’t know any of that as a child. I only knew what it felt like to want a small car so badly it became a kind of prayer. Hot Wheels promised speed, control, story. You could set up tracks and loops and decide outcomes in a world where children don’t get to decide much. In a small living room, a toy car could become an entire geography.

Superhero action figures hit us the same way—power in miniature. In the 1970s, the superhero action figure wasn’t just a toy; it was a portable mythology. Mego’s “World’s Greatest Super Heroes” line launched in 1972 and became a defining 8-inch action-figure series of the decade, with cloth costumes and a roster that pulled comic-book heroes into children’s bedrooms.

For Black boys, superhero stories carried extra layers. The heroes we saw were often not made to look like us. But we still reached for the idea of heroism because heroism offered a vocabulary for justice, secret strength, transformation—ways to imagine being more than what the world insisted you were.

Comic books completed the triangle: cars, heroes, stories. Comics were worlds you could enter for the price of a thin paperback. They were portable, tradable, and readable under covers with a flashlight. They were also literacy in disguise—reading because you wanted to, not because you were told.

What I understand now is that our wish list wasn’t only about toys. It was about belonging to the national childhood. It was about being able to name what other kids were naming, to bring the same kind of excitement into our living room, to feel included in a story America told itself about Christmas morning.

The Brooklyn mother in a Norfolk house

My mother was from Brooklyn, New York. That origin lived in her. It lived in her directness, her stamina, her skepticism about promises that didn’t come with proof. Brooklyn in the 1970s was a place where Black life held beauty and pressure in the same hand—community networks, church life, the density of people, the density of problems.

My brother and I would often travel to New York for Christmas, but primarily we celebrated in Norfolk, Virginia. The travel north felt like a shift in volume. Brooklyn had a density Norfolk didn’t—more people, more noise, more stores, more lights, a different cold that seemed sharper because the buildings held it. Norfolk had its own rhythm—port city energy, military presence, neighborhoods where people knew each other’s business and sometimes protected each other because of it.

That movement between Norfolk and Brooklyn shaped our understanding of Christmas as something both portable and rooted. You could carry it, but you still had to build it wherever you landed.

My mother built it in Norfolk with the tools available to her: work ethic, chosen family, church, furniture, light.

She worked two jobs. I keep returning to that because it is the engine of everything. Her work did not stop for December. Bills didn’t stop. Fatigue didn’t stop. But she refused to let the holiday be erased by the grind.

In our house, Christmas was not inevitable. It was assembled.

The rule before the gifts

Christmas morning never eased in. It arrived.

The living room looked different—charged, fuller, awake. The tinsel tree shimmered as if it had been plugged into the sun. The holiday fan continued its slow rotation, bathing the room in warm red, blue, and green light. The light traveled, steady and ceremonial, making even ordinary corners feel touched.

But before we touched anything—before we opened gifts—there was a rule that mattered as much as the chairs had mattered the night before:

Our mother always received her gift first.

Before we could tear paper, before we could race a car across the floor, before we could hold a hero in our hands, she sat down and accepted what we had chosen or made for her. Even as children, we understood this as law. It taught us order. It taught us gratitude. It taught us—subtly—that the person who made Christmas possible deserved to be honored before the day belonged to anyone else.

I didn’t have the language then to name how radical that was. American holiday culture has a way of making mothers invisible: the cook, the wrapper, the scheduler, the emotional manager. My mother refused that invisibility. She made sure we saw her receive.

Only then did Christmas become ours.

Morning in motion

After my mother opened her gift, the room moved fast.

Hot Wheels packaging came apart like a promise being unsealed. Cars hit the floor and immediately began to travel, tracing imaginary highways across rug and under furniture. Action figures stood in heroic defiance, ready to be assigned a story. Comic books were opened and read and re-read, pages smoothed down with careful hands.

The morning felt like a storm made of delight.

And yet, even in that delight, the fan kept turning slowly. The light kept sweeping. The room kept glowing as if it had patience for us, as if it understood that children move quickly but memory moves at the speed of atmosphere.

Christmas was always a magical time.

Not because it was extravagant. Not because life was easy. But because for a few hours, the world was reordered around joy.

By afternoon: The living room becomes evidence

By the time afternoon arrived, the living room no longer looked like a room. It looked like proof.

Wrapping paper covered the floor completely—creased, torn, folded back on itself, layered in ways that suggested urgency rather than order. Reds bled into greens. Silvers caught the light from the holiday fan and reflected it back in uneven flashes. Some pieces still clung to boxes, half-detached, as if even the paper had resisted letting go too quickly. Other pieces were balled up, kicked aside, flattened under socked feet moving too fast to care.

The room told the story of the morning without needing witnesses.

If Christmas morning was performance, afternoon was aftermath. And in our house, aftermath mattered.

The fan still turned, slow and steady, its red, blue, and green light moving across a room that now looked lived-in again—reclaimed by noise, motion, and consequence. The tinsel tree stood slightly off-center, lighter now, relieved of its cargo. Its branches bent back toward stillness, strands of silver tinsel drooping where small hands had reached too quickly, too often.

The chairs that once formed the perimeter—once the boundary between belief and discovery—had returned to their ordinary jobs. One held a coat. Another held a sweater. One became a temporary table for an opened box, its contents already spread across the floor. The perimeter was gone, dissolved into usefulness.

That disappearance felt important, even then.

As a child, I didn’t think of wrapping paper as labor. I thought of it as reward. But looking back, I understand what it really was: residue. Evidence of planning. Evidence of patience. Evidence of someone staying up late so the day could look like this.

The floor was loud with it.

Every step made a sound—crinkle, tear, slide. The living room spoke back to us with each movement, reminding us that something had happened here. That this wasn’t a quiet Christmas. That this wasn’t a Christmas where nothing arrived.

In a small two-bedroom house on a dead-end street, wrapping paper became a kind of architecture. It expanded the room beyond its square footage. It made abundance visible, even if abundance had been carefully measured, budgeted, and wrapped one box at a time.

This is something people don’t often say out loud: wrapping paper is one of the cheapest ways to signal fullness. It disguises scarcity. It turns one object into many moments. It multiplies anticipation. In working households—especially Black working households in the 1970s—this wasn’t deception. It was creativity. It was how you stretched joy without breaking yourself.

By afternoon, toys were everywhere, but they weren’t the loudest thing in the room. The loudest thing was satisfaction.

Hot Wheels cars had already left their packaging and found the floor, tracing imaginary highways across the rug and under furniture. Action figures stood in half-constructed worlds, their presence announced but not yet organized. Comic books lay open and face-down, abandoned mid-panel because something else demanded attention.

There was no rush now.

Morning had been urgent. Afternoon was permission.

And in that permission lived a particular kind of peace: the peace that comes after a goal has been met. After a promise has been kept. After children have been convinced—fully—that they were considered.

I remember glancing at my mother then, sometime in the afternoon, when the room was loud with paper and possibility. She was sitting, finally. Not collapsed, not distant—just sitting. Watching. Taking in the scene like someone who had completed a complicated task and was allowing herself to register the outcome.

She didn’t say much.

She didn’t need to.

The living room said everything for her.

It said: this happened.

It said: it was worth it.

It said: even here—even now—we had enough.

That is what the wrapping paper was really doing by afternoon. It was testifying.

It testified that Christmas had arrived fully formed, not partially delivered. It testified that the night before—when my brother and I whispered in the dark about what might be under the tree—had not been wishful thinking. It testified that the chairs, the fan, the tinsel, the midnight Mass, the borrowed Christmas Eve at our adopted grandmother’s house, and the late return of a working mother had all converged successfully.

The room did not look neat. It looked honest.

And honesty, I’ve learned, is one of the rarest gifts a holiday can leave behind.

By the time the light outside shifted—by the time afternoon leaned toward evening—the wrapping paper would eventually be gathered, folded into trash bags, cleared away. The living room would shrink back into itself. The fan would be turned off. The tree would stand quietly, waiting out the rest of December.

But for those hours, the room stayed open, messy, and loud with evidence.

Christmas had been made here.

And nothing—not fatigue, not limited space, not two jobs, not a dead-end street—had stopped it.

The neighborhood outside the window

Our house sat in a predominantly Black American community. We are Black Americans. That fact was not a footnote; it was the frame. It shaped what resources were nearby, what institutions felt accessible, what safety meant, what joy had to push through.

When I think about The Parkers holding Christmas Eve, I think about the neighborhood logic behind it: a community that survives by distributing care. When I think about my mother working late and still producing Christmas, I think about the quiet heroism that becomes normalized in Black working households—the way excellence is demanded with less margin for error.

And when I think about our living room, I think about how a small domestic space can become a political statement without anyone calling it that. The country might grade neighborhoods, starve them of loans, carve them up with “renewal” projects, and treat Black stability as negotiable. But inside our house, my mother was saying: you will have joy. You will have ritual. You will have proof that you are worthy of celebration.

The HOLC redlining map context for Greater Norfolk is one of many reminders that housing inequality wasn’t accidental—it was structured. And the city’s urban renewal history is another reminder that Black neighborhoods were often asked to pay the price of “progress.”

Christmas didn’t solve any of that. It offered us a counter-narrative: a morning that said we mattered.

Between church and toys: what we were really inheriting

When I was a child, I thought Christmas meant what I wanted: Hot Wheels, action figures, comic books, the popular toys of the 1970s that made me feel like I was inside the same childhood as everybody else.

Now I understand I was also inheriting something else: a theology of persistence.

From the Church, I inherited the idea that you show up even when you’re tired, that meaning can live inside repetition, that an hour can be consecrated. From my mother, I inherited something more practical and more radical: that love is not only a feeling. It is a schedule. It is a system. It is labor done in secrecy so children can experience it as ease.

Black Catholic history in the late 1960s and 1970s underscores that faith, for many Black Catholics, wasn’t passive. It was contested, organized, insisted upon.

Toy history in the same era underscores how consumer culture offered kids a language of desire and belonging, mediated by design and marketing.

My mother was navigating both worlds: the sacred and the commercial, the discipline of Mass and the pleasure of toys, the seriousness of work and the playfulness of childhood. She was giving us a Christmas that didn’t ask us to choose between gratitude and joy.

The older I get, the more I see

When you’re a child, Christmas happens to you. Adults are technicians behind the curtain.

When you’re older, you start to see the technicians.

You see the exhaustion behind your mother’s eyes. You see the way she built the holiday on a clock that wasn’t kind to her. You see that the adopted grandmother wasn’t just a place to sleep; she was part of an informal infrastructure that made the entire morning possible.

You also see the genius of the chairs. They weren’t only about preventing peeking. They were about giving my mother a fighting chance to make the morning she wanted for us. A boundary is sometimes a gift you give yourself so you can give something to others.

And you realize something that changes how you remember everything: Christmas magic is often the visible edge of invisible labor.

In our family, the labor was Black, maternal, Brooklyn-rooted, Norfolk-executed, church-lit, and stubbornly hopeful.

That is the story I carry.

Not that we received toys—though we did, and they mattered. But that we received a repeated lesson: even in a world that demands too much, a mother can still make room for wonder.

What the fan was really doing

Sometimes I think the fan is the most honest symbol of our Christmas.

It turned slowly. It never rushed. It didn’t care how chaotic the room became. It just kept sweeping color across everything—walls, couch, floor, wrapping paper, tinsel. It occupied every corner. It refused to let any part of the room be left out.

That’s what my mother did, too.

She occupied every corner of our lives: work, school, church, home. She kept turning, kept sweeping, kept lighting things up even when she was tired. She made a small living room feel like the center of the world.

In that two-bedroom house at the end of a dead-end street, Christmas wasn’t a miracle that arrived from somewhere else.

It was a miracle we built—together—under a tinsel tree, in rotating color, on a floor that by afternoon was covered in evidence.