KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a winter evening in New York, the kind that makes even familiar blocks feel newly strict, an audience files into a theater with the particular quiet of people who know they are about to be asked to feel something in public. A few of them have come because they have always come—because this company is a seasonal marker, a tradition, a civic habit. Others come because a friend insisted, or because a teacher assigned it, or because they once saw a photo—Black dancers in classical lines—and the image lodged itself in the mind like a dare.

What happens next will look, to a casual observer, like performance. But the longer you follow Black-owned dance theaters—Black-founded, Black-led institutions that trained dancers, commissioned repertory, toured, taught, and built physical homes—the more you realize the movement onstage is only one layer of the choreography. The deeper dance is the infrastructure: the school that stays open when funding dips, the building purchase that keeps rents from devouring budgets, the archive that prevents a generation’s masterworks from disappearing, the outreach program that persuades a city that a dance studio is as necessary as a gym. The dance is the long work of making a home.

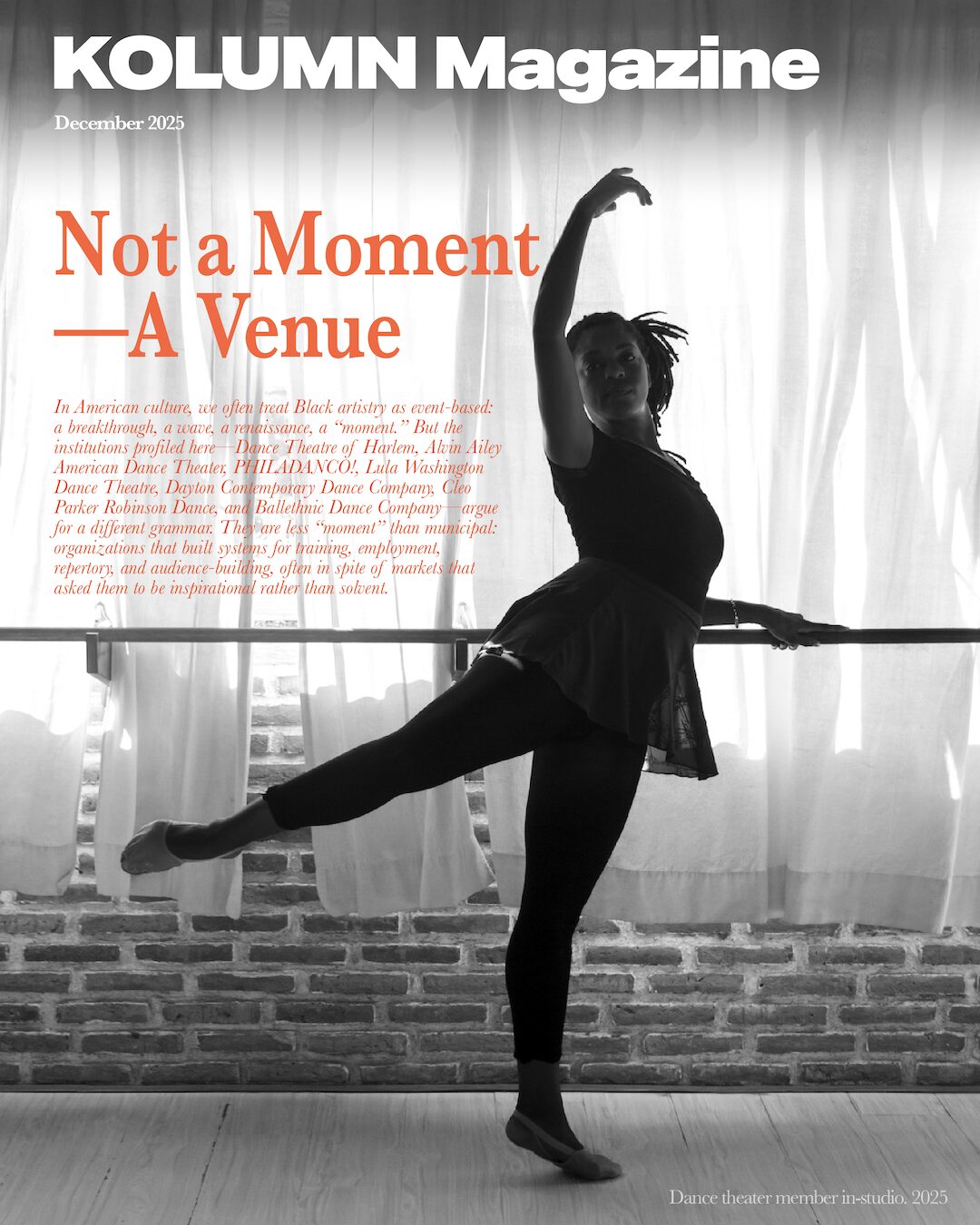

In American culture, we often treat Black artistry as event-based: a breakthrough, a wave, a renaissance, a “moment.” But the institutions profiled here—Dance Theatre of Harlem, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, PHILADANCO!, Lula Washington Dance Theatre, Dayton Contemporary Dance Company, Cleo Parker Robinson Dance, and Ballethnic Dance Company—argue for a different grammar. They are less “moment” than municipal: organizations that built systems for training, employment, repertory, and audience-building, often in spite of markets that asked them to be inspirational rather than solvent.

To call them “Black-owned dance theaters” is, in part, to name a practical truth: many of these institutions did not merely rent stages; they created and maintained spaces—schools, studios, performance venues—where Black artists could work without asking permission. Ownership here is not only legal. It is curatorial, pedagogical, architectural. It is the right to decide what counts as excellence, what is taught, what is preserved, what stories are staged, and which neighborhoods benefit from the foot traffic of art.

A founding premise: the barrier is not only aesthetic—it’s structural

Dance, perhaps more than any other major performing art, has long been policed by bodies: their proportions, their color, their presumed “fit” within inherited European forms. Ballet, especially, built an economy of exclusion that disguised itself as tradition. The Black-led institutions that rose in the late 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s were not simply reacting to taste. They were responding to a labor market that limited where Black dancers could train, audition, and be paid—and to an arts funding ecosystem that could celebrate Black culture in theory while starving Black institutions in practice.

The language of these theaters’ origin stories repeats like a refrain: we created this because there was nowhere else to go. Dance Theatre of Harlem’s founders, Arthur Mitchell and Karel Shook, launched the company and school in 1969, explicitly imagining classical ballet training and performance opportunities for children and dancers—especially in Harlem—at a moment when the civil-rights era had clarified, in public, what exclusion meant.

PHILADANCO! (The Philadelphia Dance Company) emerged from a similar necessity. Founded in 1970 by Joan Myers Brown, it was created to provide performance opportunities for Black dancers and to anchor a training pipeline through the Philadelphia School of Dance Arts.

And Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater—founded March 30, 1958—made a claim that was both artistic and geopolitical: that African American cultural experience belonged on global stages, and that modern dance could carry Black memory, spirituality, humor, grief, and joy without translating itself into somebody else’s standards.

Over time, these companies became something else, too: talent incubators and civic institutions. They trained dancers who would spread through the broader field—mainstream companies, Broadway, Hollywood, global tours—altering the labor pool and, slowly, the aesthetic assumptions of what a “ballet body” or “modern dancer” could be. But the companies did not merely produce dancers. They produced continuity.

Dance Theatre of Harlem: ballet as a public utility

Dance Theatre of Harlem is often described, correctly, as a landmark: a professional ballet company and school based in Harlem, founded in 1969 by Arthur Mitchell and Karel Shook. The deeper point is what that founding implied. To make a ballet company in Harlem was to insist ballet could be neighborhood-based—not only a downtown luxury, not only a patron’s art, but something that could belong to the children living a few blocks away.

If you want to understand DTH’s impact, you have to look at the double structure: performance and school. The company’s touring, repertory, and public identity were always braided with pedagogy and access. That braid is also what made the organization vulnerable. When financial pressures forced a shutdown of the main company in the mid-2000s, the absence registered not only as an artistic loss but as a civic wound—because the company’s school and community role functioned like a cultural community center as much as a conservatory.

The return, in the early 2010s, carried a particular kind of symbolism: not just a comeback, but an argument that the institution was worth rebuilding. Virginia Johnson—named artistic director in 2011 and credited with returning the company to full status in 2012 after the hiatus—became a visible figure for the broader message: that Black ballet wasn’t an exception; it was an inheritance and an ongoing practice.

DTH’s story also demonstrates a lesson other Black dance theaters learned: the stage is not the only asset. Repertory, alumni networks, training systems, and community credibility can function like capital—often the only kind available—when financial capital is uncertain.

Alvin Ailey: the company as ambassador, the building as ecosystem

Ailey’s origin story is famous: Alvin Ailey founds the company in 1958; “Revelations” premieres in 1960 and becomes a landmark; the organization grows into a global cultural institution. But the Ailey model is especially instructive for a conversation about Black-owned dance theaters because it shows how a company becomes an ecosystem—companies, school, extension programs, camps, community offerings—an entire organizational architecture built around one premise: dance is both art and public service.

Ailey’s official history frames that expansion as central to the mission, not incidental. A U.S. Congressional resolution has even designated the company a “vital American Cultural Ambassador to the World,” a phrase that, while ceremonial, hints at the real function Ailey has served: touring as diplomacy, repertory as narrative authority, and Black cultural expression as national export.

In recent years, the institution’s leadership transitions have underscored both its stability and its vulnerability to generational change. (Alicia Graf Mack’s selection as artistic director—following a lineage shaped heavily by Judith Jamison’s long tenure—signals how much of the company’s identity is leadership-dependent, even at scale.)

But if you want the Ailey story to speak to the broader field, you look beyond celebrity and toward infrastructure. The Ailey campus, its training arms, and its programmatic reach embody a proposition Black-owned dance theaters have repeatedly made: that control over training and rehearsal space is not ancillary—it is central to artistic sovereignty.

PHILADANCO!: repertory as rescue mission, training as insistence

In Washington Post coverage spanning decades, Joan Myers Brown is portrayed not only as a company founder but as a cultural worker who treats young audiences, and young dancers, as future stakeholders—future dancers, patrons, citizens.

PHILADANCO!’s public mission statement is often summarized as performance opportunity. But the more precise work has been preservation and commissioning: building a repertory heavily rooted in African American choreographers and keeping works alive that might otherwise disappear from the canon through neglect. The Post notes Brown’s role in commissioning and restoration efforts, as well as her decades-long commitment to performing for youth.

This is one of the most under-discussed functions of Black-owned dance theaters: they operate as informal archives. Not always with climate-controlled vaults or endowed curatorial departments—though some have built archives—but through a practical repertory economy: we keep the dances alive by performing them, teaching them, and paying dancers to embody them. In that sense, repertory is not merely programming; it is memory-work.

PHILADANCO!’s endurance also clarifies another truth: Black dance theaters often survive by diversifying function. Performance alone is rarely enough. Schools, community classes, touring fees, rentals, philanthropic relationships, and—in recent years—scholarship programs created in response to tragedy (as with the O’Shae Scholarship Program reported in 2024) form a braided revenue and mission structure that helps the institution remain legible to funders and indispensable to its community.

Lula Washington Dance Theatre: Crenshaw Boulevard as cultural center

In Los Angeles, Lula Washington Dance Theatre has long stood as an example of what it means to root a professional company in a neighborhood—and to treat the neighborhood not as audience development strategy, but as the reason the institution exists.

LWDT is widely described as a repertory ensemble founded by Lula and Erwin Washington in 1980. Yet the more striking part of the story is real estate: the purchase of a sizeable building on Crenshaw Boulevard in 1988—effectively turning a company into a community cultural center with multiple studios and instructional space.

A building purchase is not a romantic detail. In arts economics, it is a survival strategy. Owning space can stabilize costs, enable programming expansion (classes, youth ensembles, rentals), and signal permanence to donors and civic partners. It can also concentrate risk: repairs, renovations, disasters. LWDT’s building was damaged in the 1994 Northridge earthquake; accounts note FEMA support that helped rebuild.

And still, the company persisted, long enough to mark 40 years with major-profile coverage and to receive significant philanthropic investment—such as the Mellon Foundation grant reported by the Los Angeles Times in 2021—framed explicitly as an attempt to disrupt systemic inequality in arts funding.

LWDT’s example has influenced how other Black dance theaters talk about “home.” The home is not merely a rehearsal studio. It is a facility that doubles as a neighborhood institution: a place where young dancers can train in styles ranging from ballet to jazz to African forms, and where the company’s professional work sits alongside community education as equal priorities.

Dayton Contemporary Dance Company: building an archive inside the company

The Dayton Contemporary Dance Company (DCDC) began, in many ways, as a local corrective. Jeraldyne Blunden founded the company in 1968 after building a dance school for African American youth in a segregated environment; DCDC grew from that impulse into a nationally recognized organization.

What makes DCDC especially relevant in this survey is how explicitly it framed its work as historical preservation. The MacArthur Foundation’s profile of Blunden emphasizes her creation of a dance archive within the company—an institutional mechanism intended to preserve masterworks of African-American choreographers.

This is the kind of behind-the-scenes labor that rarely receives glamour, yet it changes what the field can remember. Dance is notoriously fragile as history: it lives in bodies, and bodies age; it lives in rehearsal rooms, and rehearsal rooms close. When a Black-owned institution treats archiving as core mission, it resists a broader cultural tendency to let Black innovation vanish after it has “influenced” the mainstream.

DCDC’s endurance—like PHILADANCO!’s—also reaffirms how the regional is often as consequential as the coastal. Black dance theaters flourished not only in New York and Los Angeles but in cities where the company could function as a civic emblem: an assertion that excellence can be homegrown, that training can happen locally, that talent does not need to migrate to be legitimate.

Cleo Parker Robinson Dance: the theater as a home for all

In Denver, Cleo Parker Robinson Dance (CPRD) offers a direct answer to a question Black arts leaders have asked for decades: What does it look like when a Black-founded dance institution becomes a city’s cultural anchor?

CPRD was founded in 1970, and over time developed a multi-part structure—school, ensemble, outreach—similar to other long-lived Black dance theaters. What distinguishes CPRD in the “dance theater” frame is literal theater ownership and operation: the organization describes a historic, proscenium theater space (240 seats) as part of its complex, explicitly positioning it as “home” not only for its own work but for local dance, theater, and emerging artists through rentals and shared use.

That stance—a home for all—may sound like branding until you consider the deeper implication: CPRD is not only trying to ensure its own survival. It is expanding the supply of performance space for a broader ecosystem, effectively redistributing access within a city’s arts infrastructure.

For Black-owned dance theaters, this matters because access to venues is a form of power. It shapes what can be staged, who can be paid, and which audiences can be reached without dependence on institutions that may or may not prioritize Black work.

Ballethnic: East Point, ballet, and a Southern counter-canon

Ballethnic Dance Company is often described in superlatives that carry a regional sting: Atlanta’s first and only African American professional ballet company, and the oldest of its kind in the South. Founded on January 15, 1990 by Nena Gilreath and Waverly T. Lucas II, Ballethnic was built as both company and academy—again, the familiar braid of performance and training.

What’s most compelling is how Ballethnic frames its founding as an intervention in the “token spot” logic of major ballet companies—an environment where inclusion could be capped and controlled. Ballethnic’s own history page narrates the company as a response to restricted access and as a new vehicle for Black dancers and Black-led storytelling in classical form.

The company’s story also illustrates the importance of place. To build in East Point—rather than anchoring solely in arts-district geography—is to affirm the South as a site of Black cultural production, not merely the historical backdrop to northern institutions. Coverage of Ballethnic as a “Southern Cultural Treasure” emphasizes the organization’s role in keeping dancers in the region and creating a dedicated classical ballet home.

When Ballethnic blends ballet with African-derived elements and other forms, it is doing more than fusion. It is building a counter-canon—one that does not treat Blackness as a “variation” on ballet, but as a source of ballet’s future vocabulary.

What these theaters share: a governance of care

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

The future question: what does permanence require now?

Many of these organizations were built by founders with near-mythic stamina: Arthur Mitchell, Alvin Ailey, Joan Myers Brown, Lula Washington, Jeraldyne Blunden, Cleo Parker Robinson, Nena Gilreath and Waverly Lucas. The next era will demand a different kind of stamina: leadership transitions, real-estate pressures, shifts in touring economics, and the expanding expectation that arts institutions serve as social-service partners without social-service budgets.

But there is reason for clarity, not despair. The blueprint already exists, written in decades of institutional practice:

Build training pipelines that treat young dancers as future professionals and future audiences.

Treat buildings as strategy, not vanity—space as the condition for mission.

Preserve repertory deliberately, because the canon will not do it automatically.

Tell the truth about inequity in funding and access, and build partnerships that acknowledge—not obscure—that reality.

If KOLUMN’s editorial voice insists on anything, it is that Black cultural institutions are not side stories to American life. They are American life—built in neighborhoods, sustained by families and teachers, and defended by people who kept showing up to unlock the doors.

The audience, on that winter evening, rises at curtain call. Applause is the public language of gratitude. But the more honest gratitude—if the country could manage it—would look like endowments, capital support, school partnerships, touring guarantees, and city policies that treat Black arts institutions as what they have always been: essential infrastructure.

And if you listen closely, beneath the clapping, you can almost hear the deeper rhythm: the sound of keys.