KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

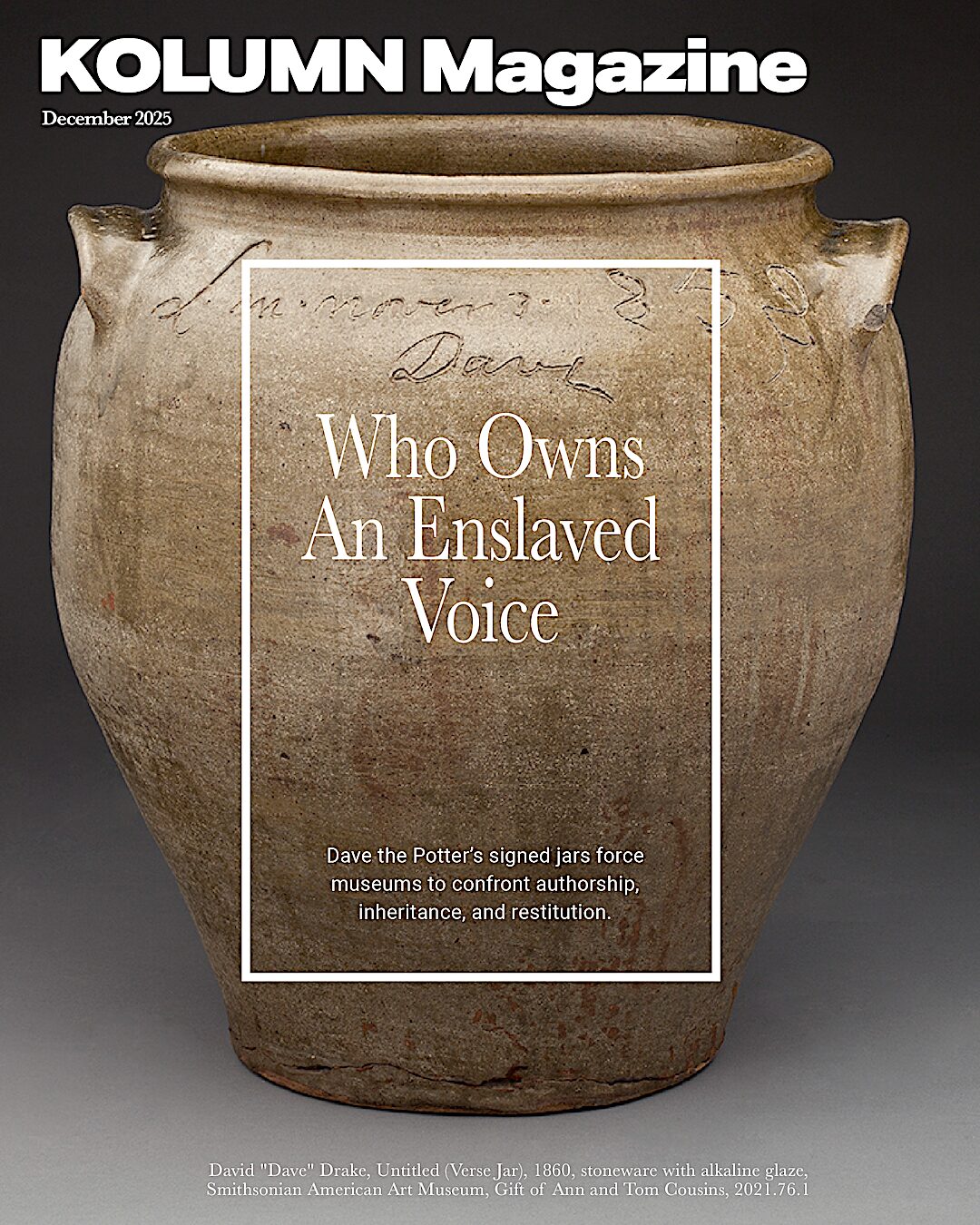

In a gallery in Boston, an elder slid her hand inside a wide-mouthed jar and searched the dark interior by touch. The jar was monumental—stoneware with a thick shoulder and a rim that had outlasted the centuries the way river stones outlast weather. Her fingertips moved along clay that had once been wet and living under another set of hands. She paused when she felt a slight rise, a small ridge in the fired earth, and she imagined it as evidence: sweat falling, a forearm brushing the lip, a thumb pressing a seam into obedience. In that instant the jar was no longer an artifact. It was contact.

The woman was Daisy Whitner, and the jar had been made by her ancestor David Drake—known to the art world, the auction world, and to generations of Black Southerners who have carried his story like a quiet inheritance—as Dave the Potter. In November 2025, Whitner and other descendants stood inside the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, as the institution restored ownership of two of Dave’s jars to his family through a landmark restitution agreement. One jar was sold back to the museum so it could remain on public view; the other stayed at the MFA on long-term loan, with ownership resting where it had always morally belonged.

That gesture—return, then purchase, then loan—sounds, on paper, like tidy legal choreography. But anyone who has ever held a family story that was stolen, renamed, and dispersed understands it differently. For descendants, the return was described as “spiritual restoration,” a closing of a circle that slavery had shattered and the marketplace had monetized. For the museum, it was framed as provenance work and an “ownership resolution,” borrowing language and structure long associated with restitution cases involving Nazi-looted art.

For Dave—who could not legally own his own body, much less the objects his hands produced—the return reads like a belated answer to a question he cut into clay in 1857: “I wonder where is all my relation / friendship to all—and every nation.”

This is an article about a man whose life was constrained by bondage and whose voice traveled anyway: through kiln heat, through alkaline glaze, through the everyday intimacy of storage jars that held meat, grain, lard, pickles, the ordinary calories of plantation survival. It is also an article about the present—about museums and markets, about the afterlife of enslaved labor, about what it means to return not just an object but an authorship. And because Dave’s early years were recorded mostly in the thin ink of other people’s paperwork, it is, inevitably, an article about how Black history often survives: in fragments, in inference, and—rarely, miraculously—in a first-person line scratched into the side of a vessel.

A life known in shards

Dave was likely born around the turn of the nineteenth century in South Carolina’s Edgefield District, an area that became an industrial center for alkaline-glazed stoneware. He lived through enslavement, the Civil War, and emancipation; he appears in the historical record in ways that are both typical for the enslaved (as property, mortgaged, bought, sold) and astonishingly atypical (as an artist who signed and dated his work, sometimes adding poetic couplets).

We know him by “Dave” because that is what he wrote. Later, after emancipation, he appears in records as David Drake, a surname scholars understand as adopted from an enslaver’s name—a grimly common practice that offered a measure of legibility in a society built to keep the formerly enslaved illegible.

There are biographies, catalogues, essays, museum labels, and children’s books that attempt to braid Dave’s life into coherence. But the central tension remains: the most vivid witness to Dave’s inner life is Dave himself—speaking not in letters preserved in archives, but in incised words that survived because they were fired into stone.

Edgefield: an industry built on Black skill

To understand Dave’s work, you have to understand where it was made—and what it was made for.

Old Edgefield was not a quaint craft village. It was a production hub where ceramic manufacturing scaled up, feeding a plantation economy that needed durable storage for food and commodities. Museums have increasingly framed Edgefield stoneware not as folk curiosity but as industrial output, and they have recentered Black makers—enslaved and free—who performed the skilled labor that made the industry profitable.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina helped formalize that shift in mainstream cultural institutions, presenting ceramic objects alongside contemporary responses and scholarship that treats these vessels as both material culture and testimony.

For decades, collectors praised Edgefield’s glazes and forms while the names of the Black craftsmen who threw the pots were absent or reduced to anonymizing labels. Dave is the exception because he refused anonymity.

The risk of a signature

To sign one’s name in the antebellum South was, for a person enslaved, not a neutral act. It was a declaration freighted with legal, religious, and bodily consequence. Literacy among enslaved people was widely feared by white authorities precisely because it disrupted the architecture of control. To read was to encounter alternative moral orders; to write was to leave evidence—evidence of thought, of memory, of authorship, of agency. In many Southern states, laws and local ordinances criminalized the teaching of reading and writing to enslaved people, framing literacy as a precursor to rebellion rather than as a human faculty. Within that climate, every letter carried risk.

This is what makes Dave the Potter so singular. He did not simply write. He wrote publicly. He wrote durably. He wrote on objects that moved through white households, plantations, markets, and storage sheds—objects that would be handled, inspected, and relied upon. His words were not hidden in a Bible margin or whispered into a hymn. They were incised into the very surface of commerce.

The risk was not abstract. Enslaved artisans were valuable commodities, but they were also subject to punishment for perceived insubordination. A signed jar could be read as pride. A poem could be read as presumption. A dated object could be read as a claim to time itself—an assertion that one’s life unfolded along a calendar rather than in the undifferentiated eternity of forced labor or exchange of ownership. Dave’s literacy did not protect him; if anything, it heightened his exposure.

Scholars have long debated how Dave learned to read and write, but the more pressing question may be why he continued. Literacy under slavery often survived through fragile arrangements: a white child quietly teaching an enslaved companion; religious instruction that blurred into letters; observation and imitation in print-saturated environments where newspapers and broadsides circulated even as Black people were forbidden to fully engage them. Whatever the source, Dave’s literacy was not ornamental. It was operational. He spelled with consistency, used meter, deployed rhyme, and adapted his writing to the curve and scale of the vessel. This was not the scrawl of novelty; it was practiced language.

Each inscription, then, functioned as a layered intervention. On one level, it authenticated the object in ways familiar to modern consumers: name, date, capacity. On another, it asserted authorship in a system that denied enslaved people legal personhood. On a third, more volatile level, it dared the reader—often a white reader—to encounter an enslaved mind speaking in the first person.

Consider the simplicity of “Dave.” No surname. No apology. Just a name repeated across decades. In a society where enslaved people were catalogued by age, sex, and price, the recurrence of that name is radical. It refuses erasure through repetition. It insists that the same person who made a jar in 1834 is the one who made another in 1857, despite sales, transfers, debts, and deaths that treated enslaved lives as interchangeable.

The poems intensify the risk. When Dave writes about repentance, he engages a Christian moral language that enslavers claimed as their own justification, subtly turning it back on them. When he writes about “relation,” he surfaces the most destabilizing truth of slavery: that it depended on the systematic destruction of family. These lines do not accuse directly; they do something more unsettling. They testify.

That testimony was preserved because clay, once fired, does not forget. Dave chose a medium that would outlast him, embedding language into utility so that it could not be dismissed as idle talk. Every jar that survives is evidence that he understood the permanence of material culture—and used it strategically.

For museums and collectors, this is where admiration must harden into accountability. Dave’s signatures are not charming embellishments. They are records of courage exercised under constraint. They are the reason his work cannot be treated as anonymous craft or folkloric curiosity. To display a Dave jar without reckoning with the danger embedded in its words is to flatten history into décor.

The risk of a signature is the risk of being seen. Dave took that risk repeatedly. The question his work now poses—to institutions, to markets, to the nation—is whether we are willing to see all the way to the end of what he signed.

Early life: what the record can—and cannot—say

When readers ask for Dave’s “early life,” they are often asking for the things slavery tried to erase: origins, kin, childhood, the first teachers, the first losses. Here, journalism has to be candid about what is knowable.

Most accounts place Dave’s birth around 1800–1801. The earliest firm documentation scholars cite includes an 1818 record describing a “boy about 17 years old” mortgaged to a creditor—language that captures, in a single line, how bondage converted adolescence into collateral.

Dave was enslaved by different men across his life, moving through an economy where enslaved artisans were both valuable and vulnerable: valuable because they possessed skill; vulnerable because skill increased the price a person could fetch. Some sources describe his connections to the Drake family and to pottery operations tied to white proprietors in the region.

How did Dave learn to read and write? The question sits at the center of his legend. Scholars have debated whether he was taught by an enslaver, learned informally in a religious context, or acquired literacy through proximity to a print culture that existed even in small towns—newspapers, broadsides, signage—while being formally barred from it. Some museum narratives suggest an early owner may have supported enslaved education for religious reasons, though definitive documentation is scarce and should be treated carefully.

Another fact often noted in Dave’s story is disability: accounts and scholarship discuss that he worked with the loss of a leg, a physical condition that makes the scale of his jars—some holding dozens of gallons—all the more astonishing. The jars are not delicate. They are heavy, thick-bodied, made to be lifted and moved. To throw them required strength, precision, and an embodied knowledge of clay that can’t be faked.

If you are trying to picture the young Dave, it helps to imagine the pottery yard itself: heat, smoke, the raw smell of wet clay and ash, the rhythm of turning and hauling, the constant presence of supervision. Dave’s early life was not an apprenticeship in the romantic sense. It was training under coercion, skill extracted for profit.

And yet, by the 1830s, he is leaving behind dated works. A jar from 1834 is often cited as an early benchmark in the surviving corpus—evidence that by his thirties, he was already confident enough, or compelled enough, to sign.

A poetics of utility

Dave’s vessels were working objects. They were meant to store food—pork and beef, brined and preserved, kept through seasons. That is part of their power: they are not art made for a salon, but art made for survival.

And yet, Dave elevated the working object into a textual surface.

Sometimes the writing functions like a label. Sometimes it turns devotional. Sometimes it flashes humor or irony—money talk, holiday talk, the kind of everyday commentary that would have been considered beneath notice if it were not carved by an enslaved man who had been denied the right to speak as a subject.

Museums and scholars now routinely describe his inscriptions as resistance—an assertion of identity and language inside a system designed to reduce him to labor. The National Gallery of Art, for example, frames his “poetic pottery” as an act that carried particular risk and meaning in a context where enslaved literacy was policed. Smithsonian writers likewise emphasize that Dave lived most of his life without the dignity of a surname, making the repeated incision of “Dave” a kind of self-portrait.

A useful way to read Dave is to hold two truths at once:

1. These jars were part of an economy that profited from enslavement.

2. Within that economy, Dave carved out a space—narrow, dangerous, miraculous—where a person could speak.

The market’s appetite—and the family left outside the room

In the twenty-first century, Dave’s jars circulate as trophies of American ceramics. Prices have risen into the hundreds of thousands and, in some cases, beyond a million dollars.

That is where the moral dissonance becomes acute: the objects made under slavery generate wealth now, and for much of modern collecting history that wealth has flowed to auction houses, dealers, collectors, and institutions—not to descendants.

In 2023, The Washington Post captured this tension with blunt clarity, writing about Dave’s work selling for extraordinary sums while descendants received nothing, and about the emotional gravity descendants felt when reading the words their ancestor left behind. That same period also saw reporting and scholarship focused on the search for Dave’s lineage—how genealogists and researchers worked to identify direct descendants, responding in a sense to Dave’s own inscribed question about “relation.”

This is the backdrop against which the 2025 restitution agreement lands—not as a feel-good museum story, but as a corrective to a long pattern in which enslaved creativity was treated as a public resource and Black inheritance as an afterthought.

The restitution agreement: what happened, precisely

In late October 2025, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston announced that it had restored ownership of two Dave jars—often referred to as the “Poem Jar” and the “Signed Jar,” both dated 1857—to Dave’s descendants.

The museum’s own account emphasized provenance research and the responsibility to reach an ownership resolution, including return when appropriate. Coverage by WBUR noted the institutional framing: a first-of-its-kind resolution for works from the U.S. slavery era, with museum leadership describing the process in the language of restitution practice.

Reporting by the Associated Press brought the story back to human scale: Whitner’s hand inside the jar, the descendants’ mixture of pride and grief, and the decision to sell one jar back so the public could continue to see it.

The Art Newspaper described the agreement as precedent-setting, explicitly comparing the contractual framework to Nazi-era restitution agreements and noting the creation of a “certificate of ethical ownership.” Smithsonian Magazine reported that descendants established a Dave the Potter Legacy Trust to manage ownership issues and invite additional descendants forward—an attempt to build infrastructure around a legacy that had, for generations, been monetized without them.

Taken together, these details matter because they show the contours of a new model: return first (as acknowledgment), then negotiate public access (as stewardship), then build a mechanism for descendants (as benefit, not symbolism). It is not perfect justice. But it is a meaningful shift in who gets to be in the room when Dave’s name is spoken.

Dave’s afterlives: scholarship, exhibitions, and contemporary echoes

If Dave had remained merely a name on a few jars in local collections, this would be a smaller story. But over the last few decades, Dave’s visibility has expanded.

Museums across the country hold his work. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History lists a jar made by Dave in 1862, explicitly identifying him as an enslaved potter working at Lewis Miles’ plantation pottery. The Met describes one of its monumental jars as a “masterwork” that reveals both technical facility and command of language.

The exhibition Hear Me Now—at the Met, then at other venues including the High Museum—helped move Black Edgefield potters from the margins of decorative arts into the center of American art history.

Artists, too, have been in conversation with Dave. Theaster Gates, whose practice has long interrogated material, labor, and Black cultural memory, has repeatedly engaged with Dave’s legacy; The Guardian has noted how Dave’s pottery appears in Gates’s exhibitions as a conduit for stories of racial oppression, spirituality, and global trade.

And in Charleston, the International African American Museum’s display of Dave’s work has been framed as part of a broader argument: that Black creativity endures even when history tries to erase its makers.

In KOLUMN terms, Dave is not simply “an artist worth knowing.” He is a case study in how Black genius persists inside systems that monetize it while denying its humanity—and how, sometimes, descendants and communities insist on a different accounting.

The meaning of “ownership” when the maker was owned

Restitution language can become sterile: title transfer, resolution, settlement, purchase back, loan agreement. But Dave’s story makes that language throb with moral pressure, because the foundational injustice is so plain.

Dave made jars he could not own. Those jars traveled into an American future that, for a long time, treated his authorship as an interesting footnote rather than a central fact. Collectors prized the object; institutions prized the object; the market priced the object. The person—Dave—was often invoked as romance: enslaved poet, miracle craftsman, “folk” genius. Meanwhile, the structural reality persisted: the wealth generated by his work flowed away from his bloodline.

The 2025 agreement does not undo slavery. It does not restore the countless other vessels Dave made—tens of thousands, by some estimates in scholarship and museum writing, though only a fraction survive and an even smaller fraction are signed or inscribed.

What it does do is force a recalibration: Dave’s work is not merely American patrimony. It is family property created under duress. The public can learn from it—should learn from it—but public learning cannot be the justification for private dispossession.

That is the ethical hinge on which this story turns.

A closer look at the poems: voice as evidence

It is tempting—especially within museum vitrines and auction catalogues—to approach Dave’s poems as charming anomalies: enslaved verse scratched into clay, a curiosity that softens the brutality of the context in which it was produced. That reading is comforting. It allows the poems to be admired aesthetically while their implications are safely contained. But to take Dave’s writing seriously—to read it as evidence rather than ornament—requires a harder reckoning.

The poems are not marginalia. They are documents.

When Dave the Potter incised language into stoneware, he was doing something structurally different from oral expression. Speech under slavery could be overheard, denied, misremembered. Writing, especially writing fired into clay, resists erasure. It fixes a moment of thought into a durable archive. In this sense, Dave’s jars operate less like decorative objects and more like affidavits: sworn statements of presence made by someone the law refused to recognize as a full person.

The content of the poems reinforces this evidentiary role. Many of Dave’s inscriptions oscillate between the utilitarian and the metaphysical, collapsing the false divide between labor and intellect that slavery relied upon. A jar might announce its capacity—“I made this jar for cash / though it is called lucre trash”—before pivoting into moral commentary. This is not accidental. By yoking function and philosophy together, Dave insists that thought and work coexist in the same body. The enslaved laborer is also a thinking subject.

Religious language appears frequently, and here again the poems do double work. Christianity was the dominant moral framework of the antebellum South, routinely invoked by enslavers to legitimate bondage. Dave’s biblical references—warnings about sin, exhortations toward repentance—appropriate that same framework and subtly redistribute its authority. He does not name oppressors. He does not argue doctrine. He simply writes as someone entitled to moral speech. In a system where Black religiosity was often tolerated only insofar as it reinforced obedience, that entitlement itself becomes evidence of resistance.

Then there are the lines that speak most directly to the interior cost of slavery. “I wonder where is all my relation / friendship to all—and every nation.” These words are often quoted, but their radicalism can be dulled by repetition. Read closely, they function as a census of loss. “Relation” here is not abstract kinship; it is the everyday family structure—parents, children, spouses—routinely dismantled by sale and forced migration. To inscribe that wondering into a jar is to make absence tangible. The vessel, designed to hold sustenance, becomes a container for grief.

What distinguishes Dave’s poems from many other surviving enslaved narratives is not only their content but their circulation. These jars moved through white domestic spaces. They were handled during meals, storage, trade. Dave’s words entered households that might otherwise have encountered enslaved interiority only through caricature or command. The poems did not ask permission. They were already there, embedded in the infrastructure of daily life.

From a journalistic standpoint, this matters because it complicates the idea that enslaved voices were wholly silenced. Dave was constrained, surveilled, and exploited—but he was not mute. His writing demonstrates how enslaved people navigated power by exploiting the small apertures it left open. Clay was one such aperture. Utility was another. A storage jar was not expected to speak back. Dave made it do so anyway.

The poems also challenge how evidence itself is defined. Traditional archives privilege contracts, letters, official correspondence—the paperwork of power. Dave’s archive is different. It is material, tactile, vernacular. It survives not because an institution preserved it, but because households found it useful. This inversion is crucial: the same economy that consumed Dave’s labor inadvertently safeguarded his testimony.

For contemporary institutions, treating these poems as evidence rather than embellishment carries obligations. It means acknowledging that Dave’s work constitutes first-person historical record. It means curatorial language must move beyond admiration toward interpretation that centers risk, authorship, and coercion. And it means that decisions about ownership and restitution cannot be separated from the fact that these objects contain the maker’s voice—one that was never meant to be owned by others.

In the end, Dave’s poems do what the best historical sources do: they refuse to settle into comfort. They speak across time with clarity and restraint, offering neither spectacle nor plea. They simply state, in line after line, that a thinking, feeling, literate person was here—and that the clay remembers, even when the nation has tried not to.

The unfinished ledger: what comes next

After the MFA announcement, reporting noted that other museums and private collectors began reaching out to the family to discuss what ethical restitution might look like. That is how precedents work: one institution makes a move, and others are forced to decide whether they are comfortable being the ones who did not.

But the road ahead is complicated. Dave’s jars are dispersed. Provenance is often murky. Enslaved people were denied consistent documentation; families were separated; surnames changed; records were destroyed or never kept. Even when a direct line can be identified, the question becomes: what is fair? Return? Financial settlement? Shared stewardship? Long-term loan with benefits? A trust that distributes proceeds to descendants?

The MFA’s model—return, then negotiate public access—offers one template. It also raises a deeper question: if institutions can create ethical ownership certificates and restitution frameworks for art stolen in other contexts, why has it taken so long to apply similar rigor to art made under slavery?

In the end, Dave’s story is not only about a man who wrote on jars. It is about an American habit: celebrating Black creation while avoiding Black claims.

The descendants in Boston—touching a ridge inside a jar, holding their ancestor’s words at eye level—are doing more than reclaiming objects. They are insisting that the country’s cultural memory include a material truth: the maker’s family exists, still, and the legacy is not abstract.

Dave asked where his relations were. The museum’s paperwork says, at last, here.