By KOLUMN Magazine

On most mornings at the Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park, the room behaved the way American memory often behaves. It filled with visitors. It quieted itself. It arranged its expectations neatly: the war at home was a story of unity; the home front was where ordinary people became heroic; Rosie was a shorthand for a nation that discovered women’s competence, briefly, and then rewarded it with a legend.

Then Betty Reid Soskin would begin speaking, and the legend would acquire weight.

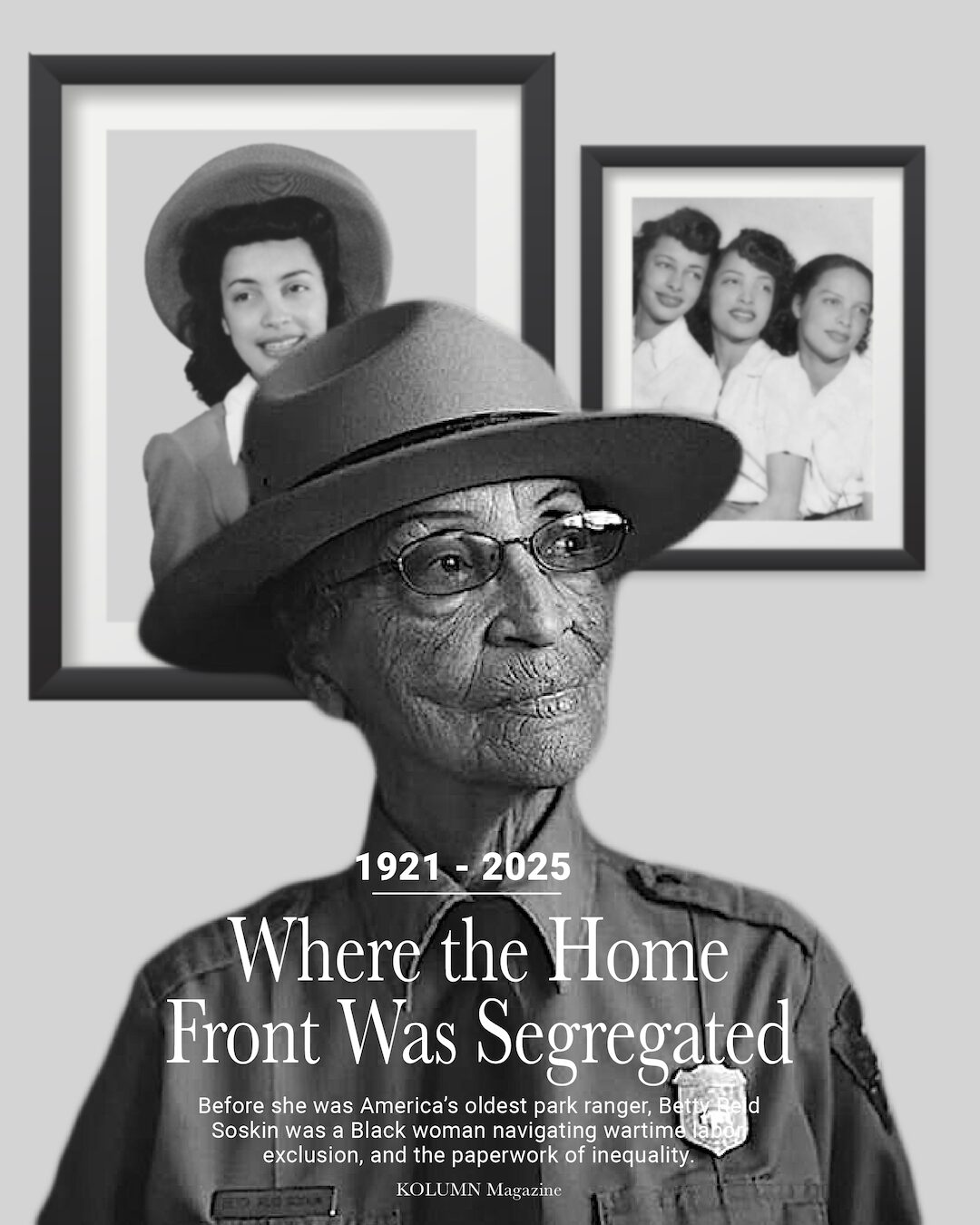

She did not do this by raising her voice. She did it by refusing to let the story stay convenient. In a Department of the Interior interview conducted when she was 93—already famous as the oldest active National Park Service ranger—Soskin explained her premise with the kind of unadorned clarity that leaves little space for argument. In 1942, she said, she was a 20-year-old file clerk in a Jim Crow segregated union auxiliary—Boilermakers Auxiliary 36—because, as a young woman of color, her employment options after high school were severely limited.

That is not the version of World War II many visitors arrive expecting. It is not a poster. It is not a slogan. It is not a flexed arm. It is the paperwork behind the iconography: the nation mobilizing for democracy abroad while maintaining caste at home—efficient, bureaucratic, polite enough to pass as “just the way things were.”

By the time many Americans learned Soskin’s name, the headline-ready facts were irresistible: she became a ranger at 85, worked at Rosie the Riveter in Richmond, California, and retired at 100—an outlier so dramatic it felt like an exception to ordinary time. But Soskin’s point—repeated in tours, interviews, and her memoir—was that her life wasn’t an exception at all. It was an illustration of the rule: Black women have always been here, always been working, always been organizing a world—often without the nation’s permission, often without the nation’s record keeping, and sometimes without even the nation’s curiosity.

The ranger uniform made the curiosity easier to manage. It turned attention into a civic transaction: you came to learn “the Rosie story,” and you left with a wider account of the home front—one that included segregation, exclusion, and the people who still managed to build ships, raise families, write music, and argue the country toward something closer to honesty.

Soskin died at home in Richmond, California, on December 21, 2025, at age 104, according to multiple reports and her family’s announcement. The fact of her death—on the winter solstice, her family noted—invited the kind of poetic framing America loves to apply to its elders. But Soskin spent her life resisting poetic framing when it blurred the facts. The real poetry, if you want to call it that, is the rigor of her insistence: tell the story as it was, not as we wish it had been.

To do that, you have to begin where she began—before the park, before the uniform—inside the early lessons that formed her sense of how a country trains you to accept your place, and how you decide whether you will.

Early life: flood, migration, and the choreography of race

Betty Reid Soskin was born Betty Charbonnet on September 22, 1921. Authoritative biographical sources, including the National Park Service, note that she was born in Detroit, raised in New Orleans, and that her family moved to Oakland, California, after the catastrophic flood of 1927 devastated New Orleans. That migration—triggered by disaster, shaped by Black labor networks, and aimed toward the West Coast—was personal and emblematic at once. The National Park Service’s Rosie the Riveter biography ties the family’s relocation to broader patterns of Black migration connected to railroad work—families whose knowledge of the West came through employment and movement.

In most short biographies, the flood functions like a plot device: calamity, relocation, fresh start. Soskin’s sensibility was less romantic. The flood was not a narrative twist; it was a demonstration of how quickly the ground can change under you, and how often Black families are expected to rebuild with limited institutional support. If you grow up hearing stories of what was lost and what had to be remade, you develop a certain fluency in contingency—the understanding that “security” is frequently conditional, and that survival is not an accident but a practice.

Her family background also complicates the binary frame through which America often narrates Black life. The National Park Service describes Soskin as being raised in a Cajun-Creole, African American family. Creole identity in Louisiana can carry its own complex history of language, class, and color—nuances that are often flattened when the story is retold for national audiences who prefer two neat categories. Soskin grew up inside those nuances. That matters because she became, later, a public historian who refused simplification not as an academic habit but as a lived necessity.

When the family arrived in Oakland, they entered a region that many Americans imagine as freer than the South. Soskin was careful to puncture that myth. In her Department of the Interior interview, she frames California not as liberation but as a different style of restriction—racism that could present itself as “normal,” “neutral,” “procedural.” The geography changed; the hierarchies adapted.

For a Black girl in the Bay Area, the lessons were often delivered quietly: through neighborhoods where you were discouraged from living, schools where expectations were shaped by race, jobs where advancement depended on access to networks you were not meant to enter. These were not merely social inconveniences. They were systems—durable structures that managed opportunity in ways that could be explained away as happenstance if you didn’t look too closely.

Soskin looked closely. Her personality, as she later displayed it in the visitor center, was not loud. It was exacting. That exactness was trained early by necessity: Black children learn to read rooms because misreading a room can be costly.

In the DOI interview, Soskin explains that when she graduated from high school, her employment possibilities as a young woman of color were largely limited to agricultural work or domestic service. This detail lands like a ledger entry: the country’s options, written plainly. It also reveals something about Soskin’s later refusal to romanticize the Rosie icon. World War II did not “introduce” work to women like her. Work was always there. The nation’s willingness to recognize certain kinds of women’s work was what fluctuated.

Those early restrictions didn’t shrink Soskin’s worldview; they clarified it. They taught her what it means when a nation claims universal ideals and then distributes them selectively. That lesson would become central to the way she narrated the war years—years that are often remembered as a time of collective purpose and, in her telling, were also a time of carefully maintained inequality.

World War II: A file clerk in the machinery of segregation

The WWII home front has become a kind of American comfort story—an era to revisit when the present feels fractured, a time when the nation appears to have rallied around a shared mission. The Rosie the Riveter icon, in particular, is used as shorthand: women entered factories, proved their competence, and forced a cultural shift.

Soskin did not deny the importance of women’s wartime labor. She did something more difficult: she insisted on specificity. During World War II, she worked as a file clerk in the segregated union hall of Boilermakers A-36 (often referenced as a segregated auxiliary connected to the Boilermakers), a fact the National Park Service highlights prominently in its biography of her life and career.

To understand what that means, you have to see the war as an industrial and bureaucratic project as much as a moral one. The Bay Area—especially Richmond—became a wartime engine, with Kaiser Shipyards building vessels at a rate that symbolized American productivity. The nation needed labor. It recruited women. It recruited Black workers migrating from the South and from other regions. It did not, in many places, dismantle segregation to do so. Instead, it built workarounds: segregated housing patterns, segregated job classifications, segregated union structures.

Soskin’s job title—file clerk—can sound modest, but the files were the story. A file cabinet holds the evidence of how democracy behaves when it thinks no one is watching: who gets hired into what role, what wages and protections accompany that role, how grievances are processed, what “membership” means, and who is allowed full membership in the first place.

In the DOI interview, Soskin explains the logic behind the segregated union auxiliary: labor unions were not yet racially integrated; they created all-Black unions for workers. The phrasing carries an institutional neutrality that she did not share. The structure was not benign. It was a mechanism that extracted labor while limiting power.

This is one of Soskin’s most enduring contributions as an interpreter: she reintroduced the war’s internal contradictions into a story that often glosses them. The United States fought fascism abroad while sustaining racial hierarchy at home. Many Americans prefer to treat that as “complicated” in a way that allows them to move on. Soskin treated it as definitional: the contradiction mattered because it shaped what came after.

If Black workers could be essential to building ships and winning the war, why were they excluded from full union membership? If the nation could mobilize for democracy, why were Black citizens still asked to live under second-class conditions? The war, in her telling, wasn’t just a story of victory. It was a staging ground for postwar demands for civil rights—a moment when hypocrisy became harder to hide because the nation’s own rhetoric was so loud.

Soskin also resisted being placed neatly inside the Rosie mythology. She was often described in popular coverage as connected to the Rosie story—because she worked on the wartime home front—but she insisted on the distinctions. Her experience was not “Rosie as icon.” It was a Black woman’s experience inside a segregated labor system that the icon tended to omit.

This refusal to let the story become a poster would later define her ranger work. Visitors came expecting a single narrative of empowerment and unity. Soskin gave them a set of intersecting narratives: empowerment for some, restricted opportunity for others, and a war economy that needed everyone while maintaining stratification.

She understood that the story of WWII is not weakened by truth. It is strengthened. A democracy that can admit its contradictions has a chance to address them. A democracy that requires myth as a substitute for memory becomes brittle—vulnerable to manipulation, nostalgia, and selective empathy.

After the war, Soskin did not retreat into private life. She built institutions—small enough to be overlooked by national headlines, important enough to shape a community’s daily reality.

Reid’s Records: a storefront that functioned like an archive

Long before she wore a ranger hat, Soskin understood something fundamental about history: if institutions would not preserve Black life with care, Black people would have to do it themselves. Reid’s Records—founded in 1945 with her husband Mel Reid—was one of those preservation strategies disguised as commerce. The National Park Service biography identifies the store as one of the first Black-owned music stores in the area and notes that it operated until its closure in 2019.

The store opened at a moment when the country was congratulating itself for surviving the war, even as it quietly resumed the racial habits it had merely paused. Wartime mobilization had expanded the Black population of the Bay Area; postwar demobilization threatened to contract opportunity again. For many Black families, the question was not whether to retreat, but where to anchor. Reid’s Records became one such anchor.

To call it a record store understates its function. In Black neighborhoods across mid-century America, record stores operated as informal libraries, newsrooms, and community centers. They were places where the past was stocked on shelves and the present arrived weekly in cardboard sleeves. In the absence of mainstream institutions willing to treat Black culture as historically significant, these storefronts did the work themselves—curating, circulating, remembering.

Soskin understood this instinctively. Music was not merely entertainment; it was documentation. Gospel testified to endurance; blues narrated survival; jazz argued for intellectual and emotional freedom. To sell records was to distribute a people’s philosophy.

Reid’s Records served customers who were themselves recent arrivals—Southerners drawn west by wartime industry, Black servicemen returning with different expectations of the country they had defended, families making new lives under new constraints. The store offered something more durable than optimism. It offered recognition.

The business also represents a particular form of Black women’s labor that history routinely mislabels as secondary. Soskin was not only co-owning and operating a business; she was performing curatorial work—deciding what mattered, what should be available, what deserved shelf space. That curatorial instinct later reappeared in her park work, where she made similar decisions under a different name: interpretation.

It is worth pausing on the timing. Reid’s Records opened in the same year the war ended. The nation pivoted from emergency to normalcy. For many Black Americans, “normalcy” meant renewed pressure to know one’s place. Soskin’s response was not withdrawal. It was infrastructure.

When the store closed in 2019—near the end of her formal ranger career—coverage framed the closure as the end of an era. In Soskin’s life, it reads as the completion of a long chapter in a much larger archive she had been assembling across formats: songs, speeches, policy work, oral history, and finally public interpretation.

For a generation that came to know her primarily as “Ranger Betty,” the record store complicates the image in productive ways. It shows her as a cultural worker before she was a public historian; as someone who understood, early and deeply, that history is not only written by scholars or preserved by governments. It is stocked daily, played repeatedly, argued over at counters, carried home in paper bags.

Reid’s Records mattered because it treated Black life as worth archiving in real time. Decades later, when Soskin stood in a National Park Service visitor center insisting that the WWII home front include Black women’s labor and segregated unions, she was doing the same work—just with federal backing instead of vinyl sleeves.

Politics and movement work: the long arc between the street and the state

Soskin’s life moved across domains—war work, entrepreneurship, then politics—but the movement makes sense when you see the throughline: she was always studying systems and building counterweights.

The National Park Service notes that over the years she served as staff to a Berkeley city council member and as a field representative for California Assemblywoman Dion Aroner and later Senator Loni Hancock. Field work is its own education. It teaches you how policy becomes lived consequence—how a decision made in a meeting becomes a housing shortage, a school boundary, a policing practice, a development project that changes who can afford to stay.

It also teaches you how narratives are managed. Politicians are in the business of framing: what to highlight, what to downplay, what to call “progress,” what to label “unfortunate,” what to treat as a priority and what to treat as too controversial to touch.

Soskin’s activism—often described in obituaries as “lifelong”—was not a single era of marching and then retirement into private life. It was continuous civic labor. She lived through decades when civil rights was not one movement but many overlapping fights: labor fights, housing fights, fights over schools and representation, fights over whose communities would be protected and whose would be sacrificed to growth.

The backlash was real and personal. The Associated Press obituary notes that racism included a cross burned on her front lawn. That detail belongs to a lineage of intimidation meant to discipline Black civic presence. It is not merely a dramatic anecdote. It is evidence of the cost of refusing to be quiet.

AP also notes that she was a delegate to the 1972 Democratic National Convention—another marker that places her inside national political currents at a moment when civil rights gains were being contested, reinterpreted, and, in many cases, contained.

Soskin’s later fame as an interpreter can obscure this political chapter, but it is essential to understanding her ranger work. By the time she entered the National Park Service, she had decades of experience watching institutions produce partial truths and call them “history.” She had decades of experience navigating what happens when you insist on a fuller account.

She was, in effect, trained for the job long before the job existed.

When public history tried to skip over segregation

The Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park exists because the nation decided the home front deserved preservation and interpretation. But a park is not neutral. It is an argument—about what matters, what deserves federal attention, what is worth telling visitors, what gets called “heritage.”

Soskin entered the park’s story not as a ranger at first, but as a person watching how the narrative was being constructed. The AP obituary explains that she began working with the National Park Service later in life and used her platform to highlight overlooked contributions of African Americans during World War II, including the story of the Port Chicago disaster. People magazine similarly notes that she served as a consultant during the park’s formation and helped ensure the park addressed segregation and highlighted African American contributions.

This is where her identity as a witness mattered most. Park planning can easily default to the most familiar version of history—the version already circulating in public consciousness. “Rosie” is familiar. “Home front unity” is familiar. “Industrial triumph” is familiar. The question Soskin posed—sometimes explicitly, sometimes through her mere presence—was: familiar to whom? And at whose expense?

Her experience in a segregated union auxiliary meant she could identify the missing pieces instantly. She had lived the parts of the story the myth preferred to omit. She knew which buildings and sites carried a racial history that would be erased if not named.

The National Park Service describes Soskin as a spokesperson for diverse domestic war-effort experiences and places her at the center of interpreting WWII home-front labor beyond the dominant iconography. In plain terms: she helped expand what the Park Service itself considered legitimate public history.

It’s easy to assume public history is simply the past presented nicely. Soskin’s life is a reminder that public history is a negotiation—often a struggle—over what will be said out loud and what will remain background noise. She understood that if segregation is not named, it doesn’t become less important; it becomes invisible. And invisibility is a political outcome.

Becoming “Ranger Betty”: the uniform as leverage, the voice as evidence

Soskin was hired as a ranger at Rosie the Riveter at age 85, according to multiple reports, including AP and The Guardian. The fact itself became a headline because American culture rarely expects elders—especially Black women elders—to begin new public roles late in life. The subtext was always: isn’t it remarkable she is still working?

Soskin’s version of the story was sharper: the work was necessary, and she was uniquely equipped to do it.

In the DOI interview, she provides a photograph captioned as “Betty’s Hat”—an image of her at 20 years old in April 1942, a month before her wedding, when she was a file clerk in the Jim Crow segregated union auxiliary. The photograph functions like a bridge between eras: young woman in the machinery of segregation, elder in a federal uniform narrating that machinery to strangers.

She used the uniform as leverage—not to demand reverence, but to command attention long enough to deliver context. Visitors came expecting a neat story. She offered a layered one: women’s labor and women’s exclusion; industrial mobilization and institutional segregation; national unity and the stratified realities that unity covered.

Her tours became renowned for their candor. She talked openly about how Black workers experienced the wartime boom differently, and how Black women’s contributions were often omitted from the popular Rosie narrative. She also foregrounded broader wartime injustices that help explain the postwar civil rights struggle—such as Port Chicago, where Black sailors were disproportionately assigned dangerous labor and later faced prosecution after refusing to return to unsafe conditions following a catastrophic explosion. AP notes Soskin’s role in highlighting Port Chicago as part of the WWII story that visitors needed to hear.

This is where Soskin’s interpretive style aligns with the best of media narratives: she treated history not as a collection of inspiring vignettes but as a structure of cause and effect. The war did not simply “change” America; it intensified and exposed existing inequalities. The home front did not simply “mobilize”; it redistributed labor under existing hierarchies.

And she made a point of distinguishing her own experience from the simplified Rosie myth. She was not selling a feel-good version of her life. She was offering evidence.

People came for the novelty of her age. They left carrying the burden of a more honest story. That burden is, in Soskin’s worldview, a form of respect. You don’t honor the past by making it pretty. You honor it by telling it fully.

The cost of visibility: violence, aging, and the discipline of returning

American culture loves elders as symbols as long as those symbols remain harmless. Soskin’s visibility carried risk—because to be visible as a Black woman who tells uncomfortable truths is to disrupt someone else’s preferred narrative.

In 2016, when she was in her 90s, Soskin was attacked during a home intrusion and robbed—an incident widely reported at the time and later recalled in retrospectives as part of the cost of public visibility. (Recent obituaries tend to summarize her later-life challenges while emphasizing her return to public engagement.) The event mattered not only because it was cruel, but because it demonstrated how fragile safety can be even for someone celebrated nationally.

For Soskin, the key question after such incidents was always the same: will this shrink the world? Terror aims to reduce a person’s life to caution. Soskin’s pattern—repeated across chapters—was refusal. Continue anyway. Tell the story anyway. Return, if you can, to the work that gives meaning to the day.

She also experienced a stroke in 2019 while working at the park, a detail noted in biographical summaries and later coverage. Her continued association with the park and her public presence afterward reinforced a point that became central to her legend: longevity, for her, was not passive survival. It was sustained civic labor.

The temptation, when writing about someone who lived to 104, is to turn age into spectacle. Soskin resisted that flattening. Her long life mattered because of what it allowed: she was still alive to correct the record, and she felt responsibility to do so while she could.

Retirement at 100: closing the formal chapter without ending the work

Soskin retired from the National Park Service in March 2022 at age 100, according to multiple reports. Retirement, in the American imagination, is supposed to be an ending: the conclusion of labor, the start of rest. Soskin’s life complicates that, too. Much of her work—writing, speaking, being a reference point for public memory—continued regardless of formal employment status.

People magazine notes her retirement at 100 and describes how she began working with the National Park Service after consulting during the park’s formation. In these summaries, a pattern appears: the nation keeps returning to the milestone numbers because numbers are easy to share. Soskin’s contribution is harder to reduce. She changed the story the institution told.

What she did—what the Park Service sometimes struggles to do without pressure—is insist that the WWII home front narrative include Black experience not as supplemental color, but as structural fact. That insistence matters even more now, in an era when public institutions face increasing conflict over what parts of history are “appropriate” to teach. Soskin treated that conflict as evidence: if you are being told to avoid certain facts, you should ask who benefits from the avoidance.

Death at 104, and what remains in the visitor center after the witness is gone

Soskin died on December 21, 2025, at her home in Richmond, surrounded by family, according to AP and other reporting. Obituaries emphasized her role as the oldest National Park Service ranger and her lifelong activism. People noted that the family requested donations to her namesake middle school and to complete a documentary, Sign My Name to Freedom.

There is something almost too neat about the way America now receives Soskin: a beloved elder, a symbol of service, an inspirational story. That is true as far as it goes, but Soskin’s life argues for a more demanding inheritance.

Her story is not primarily about living a long time. It is about what she did with the time: she spent it widening the national frame. She forced a public institution to include what it might otherwise have softened. She gave visitors the kind of knowledge that doesn’t always make you feel good but makes you more capable of seeing the present clearly.

What remains, after a witness dies, is the question of whether the institution will continue to honor the witness’s standards. Will the park keep telling the fuller story when the person who insisted on it is no longer there to correct the drift? Will visitors continue to come expecting myth—and leave with a more honest history?

Soskin’s legacy, at its best, is not the image of a ranger hat. It is the method behind the hat: the discipline of accuracy, the refusal of convenience, the insistence that public history is a civic obligation rather than a comfort product.

She lived a century that asked Black women to be quiet, then chose a profession—public interpretation—that required her to speak. She spent decades building local cultural infrastructure, then used federal authority to scale that work. She made herself, in the most literal sense, part of the national record.

And she left behind an instruction that is both simple and difficult to follow: if you love the country enough to tell its story, you must love it enough to tell it truthfully.