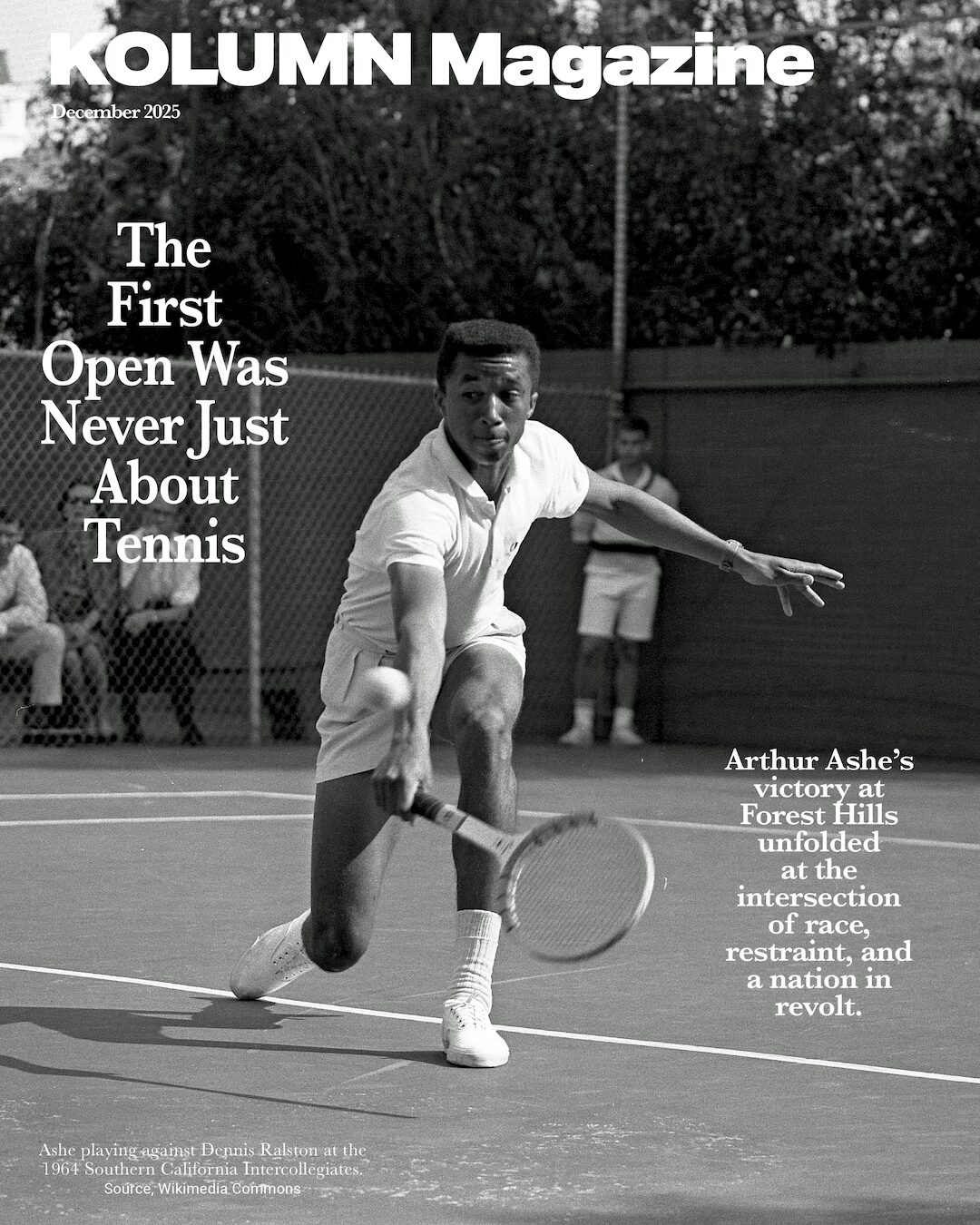

KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

The grass at Forest Hills didn’t look revolutionary. It looked trimmed, preened—an obedient green meant to reassure. White lines, white clothes, a stadium that had hosted polite summers long before America learned how to televise its turmoil in color.

But by September of 1968, reassurance was a lie the country could barely afford.

That year is remembered as a ledger of ruptures: Dr. King murdered in April, Robert Kennedy in June, cities learning the language of sirens and smoke, a Democratic convention in Chicago that played like a national nervous breakdown. The Olympics in Mexico City would soon show two Black sprinters lifting gloved fists to the sky. Meanwhile, in New York, tennis decided—almost sheepishly—to modernize itself. Professionals and amateurs would finally be allowed into the same bracket. Prize money would be offered openly. “Open tennis,” the U.S. Open’s own institutional memory notes, began at the U.S. Championships on Aug. 29, 1968—tennis stepping into a new era with a new name and a new economy.

It is one of sport’s quiet tricks that it can make change feel procedural. A rule change. A new designation. A tournament renamed. The violence, the exclusion, the long social argument underneath—those things are rarely announced by the scoreboard.

And then a young man from Richmond walked onto that grass and made the subtext unavoidable.

Arthur Ashe was 25 years old, bespectacled, and already famous within tennis for something that looked like composure and felt, to many who understood the era, like training. He was an Army lieutenant stationed at West Point. He was also, in the most literal sense, a product of where he had been allowed to exist.

Because Ashe did not discover tennis as a pastime the way the sport would like to imagine its champions discover it—through country clubs and summer camps and a casual inheritance of leisure. Ashe learned tennis at Brook Field in Richmond, a Black-only public playground during segregation, where his father’s job as caretaker came with a small house inside the park. Tennis was not the activity of privilege there; it was something a boy could do because the courts happened to be near his front door.

That fact—the geography of permission—matters. It is the first and most American element of Ashe’s story: not talent, not grit, but access, limited and policed, that still somehow produced excellence.

Brook Field: the park inside the line

In Richmond, the line was not metaphorical. It was signage, policy, sidewalks that turned into borders. Ashe was born in 1943 into a city where segregation shaped everything from schools to recreation. His mother died when he was young; his father, strict and steady, raised Arthur and his younger brother, Johnnie, inside the routines of a Black middle-class household that still lived under Jim Crow’s ceiling.

Brook Field Park—18 acres, tennis courts included—was one of the spaces Richmond designated for Black residents. The family home sat inside that space because Ashe’s father worked there. A boy could walk out the door and into the game, but the game itself was already teaching him what it meant to be contained.

He was small, studious, an avid reader. He also had that early athletic fluency that coaches recognize before the child does: coordination, curiosity, the ability to repeat a movement until it improves.

Around age seven, Ashe’s talent was noticed by Ron Charity, a gifted Black player and part-time instructor who began teaching him strokes and proper form. The relationship reads, in retrospect, like the beginning of a relay: one Black man handing a Black boy the technical vocabulary of a sport that often pretended Black people weren’t there.

Charity did more than teach. He facilitated passage. By 1953, it was clear Ashe needed a broader competitive ecosystem, and Charity introduced him to Dr. Robert Walter Johnson of Lynchburg—the physician-coach who had trained Althea Gibson and built an American Tennis Association (ATA) pipeline for Black talent.

If Brook Field was the space where Ashe found the game, Johnson’s program was where he learned what the game demanded from Black bodies in white spaces.

Dr. Johnson’s curriculum: strokes, strategy, and racial etiquette

The ATA existed because the mainstream tennis establishment largely did not. Its development programs became, for decades, a parallel institution—an answer to exclusion. Dr. Johnson established the ATA Junior Development Program in 1951, training players at his home court in Lynchburg.

Ashe spent summers there from the time he was about ten. He learned to read the spin of a ball, yes, but he also learned to read rooms.

Encyclopedia Virginia describes Johnson teaching his Black players to play every shot—whether in or out—as a way to eliminate friction in a white sport; he taught composure, etiquette, and the “composed court manner” that became Ashe’s hallmark. The point wasn’t only sportsmanship. It was survival. A Black boy’s anger could be used against him. A Black boy’s complaint could be dismissed as insolence. So the discipline became internal: hold your posture, hold your face, keep the argument quiet enough to pass the gate.

In Black communities, we understand this kind of training instinctively. We have other versions of it—what a parent tells a child before they walk into a school that might treat them as suspect, what a coach tells an athlete who will be the only one of their kind in a locker room, what a grandmother calls “knowing how to carry yourself.” Ashe learned that knowing at an elite level, while also learning to hit a backhand cleanly.

He won within the Black tennis world early—capturing ATA titles and gradually forcing his way into integrated competition. But even as he progressed, Richmond offered him limited pathways. There were few courts available to Black players outside Brook Field; white clubs and tournaments were often closed.

So, like many Black talents before the civil-rights legislation fully changed the legal atmosphere—and long after it changed the paper atmosphere—Ashe had to leave home to find a fairer field.

Leaving Richmond to find opponents

Ashe attended Maggie L. Walker High School in Richmond, an all-Black school during segregation. But to get the competition he needed, he spent his senior year in St. Louis, living with Richard Hudlin, a tennis official and contact through Johnson’s network.

This move is easy to read as a sports decision. It was also a social fact: for Black excellence to be recognized, it often has to travel.

Ashe graduated first in his class and accepted a scholarship to UCLA, a program that could match his ambition. At UCLA he thrived—academically and athletically—and won the NCAA individual championship in 1965.

By then, he was already threading a needle: becoming visible in a sport whose structures had not been built to hold him.

The soldier and the amateur

After UCLA, Ashe served in the U.S. Army from 1966 to 1968, stationed at West Point and rising to first lieutenant. He kept playing tennis through service—an athlete in uniform, navigating another institution with its own rules of presentation and hierarchy.

In 1968, tennis’s institutional rules collided with tennis’s new commercial ambitions.

The U.S. Championships were rebranded. Professionals were now allowed. Prize money was now part of the public premise. In theory, this was liberation: the sport stepping into honesty about its economy.

But Ashe, because of his status and the era’s bureaucracy around amateurism and eligibility, could not accept the winner’s purse.

That is the second American element of this story: even when the door opens, the fine print decides who gets to walk through with full reward.

Forest Hills: the match that opened the era

On Sept. 9, 1968, Ashe faced Tom Okker of the Netherlands in the final. Ashe won in five sets: 14–12, 5–7, 6–3, 3–6, 6–3.

The first set alone ran to 14–12 in a time before tiebreakers. Ashe served 26 aces across the match—an assertion of control that reads, even now, like a refusal to negotiate.

Andscape notes the crowd size—7,100 spectators at the West Side Tennis Club—and frames the victory as his 26th straight win since late July. In other words: this wasn’t a fluke. It was a surge.

If you want to understand how a Black athlete becomes “inevitable” in a white sport, you start here: not with applause, but with repetition so convincing it becomes harder to explain away.

Ashe beat Okker, and with that, became the first Black man to win the men’s singles title at the U.S. Open—and, in the open-era context, the first Black man to win a men’s Grand Slam singles title.

Then came the administrative absurdity that has outlived many match details: the winner’s check did not go to the winner.

Because Ashe was still an amateur, the $14,000 first prize went to Okker, while Ashe received a per diem—$20 a day, according to later accounts compiled in TIME’s 50th-anniversary reflection and ESPN’s historical recap.

It is difficult to imagine a cleaner parable: the Black man makes history; the system pays someone else.

The subway ride: fame, anonymity, and what America chooses to see

One of the reasons Ashe’s 1968 victory continues to invite writers is that it contains cinematic details that feel too symbolic to be true—except they are documented.

TIME, reflecting on never-before-published photographs by LIFE/TIME photographer John G. Zimmerman, describes Ashe taking a solitary subway ride between Midtown Manhattan and Forest Hills around the tournament’s final stretch—images that emphasize how ordinary the moments around greatness can be. The photographs show him unrecognized on public transit the day after winning, the trophy’s significance existing in a city that could still fail to register the man holding it.

This is the third American element: the ability of the nation to treat Black achievement as both spectacle and invisibility, depending on the angle.

Ashe himself understood the politics of winning. TIME quotes him, via LIFE’s coverage, saying: “I can make my protest heard by winning. People don’t listen to losers.”

That statement is not just athlete confidence. It is political strategy, sharpened by the reality that dignity alone rarely moves institutions. Results do.

What Ashe had to be, on purpose

There is a temptation, especially in mainstream sports storytelling, to flatten Ashe into “class”—into the idea that his calm demeanor was simply personality. The historical record suggests it was also instruction.

Encyclopedia Virginia is explicit about Johnson’s training: composure, etiquette, the elimination of “friction,” a kind of practiced grace under conditions that did not offer Black players the benefit of emotional range. The Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery blog, situating Ashe at Forest Hills during a summer of racial discord after King’s assassination, emphasizes his “characteristic nonchalance” amid spectacle.

Nonchalance can be real. It can also be armor.

In 1968, the country was loud with competing demands on Black public figures: be militant, be grateful, be quiet, be inspiring, be angry, be entertaining. Ashe was not built for the loudest version of that stage. He was built—by family discipline, by Johnson’s regimen, by the burden of being early—into something more surgical: a man who could enter hostile rooms and still appear to belong there.

That capacity is easy to misread. It is also a form of labor.

The first U.S. Open as a mirror

It matters that Ashe won the first U.S. Open, not merely another edition of an existing tournament. Open-era tennis was, at least rhetorically, about fairness: letting the best players compete regardless of status, and letting them earn openly.

But fairness arrived unevenly.

Ashe’s amateur status, tied to eligibility requirements and his military context, meant he could not accept the winner’s purse. The open era began with a Black champion who could not access the era’s new economic promise.

If you are looking for the larger meaning of the moment—beyond tennis—you find it here: the way American institutions often celebrate “firsts” while maintaining policies that blunt the material impact of being first.

Ashe held the trophy. Okker got the check. Tennis got its modern storyline.

And Ashe, as he would do throughout his life, held both the honor and the contradiction without theatrics.

The wider Black tennis lineage Ashe carried

Ashe’s win also sits inside a longer Black tennis history that is too often footnoted rather than foregrounded.

The ATA pipeline exists because the sport’s mainstream bodies excluded Black players. Althea Gibson, trained by Dr. Johnson, had already broken through earlier Grand Slam barriers, becoming a symbol and a precedent. Ashe, arriving later, carried that precedent into the men’s game, and into a national moment that was newly attuned to Black excellence as political fact.

Word In Black, in a contemporary reflection on the next generation of Black tennis stars, describes Ashe as one of the first Black male players to take the ATA by storm and underscores his singularity in the men’s record books. Ebony, in a piece focused on young prodigies and legacy, similarly frames Ashe as a figure of “firsts,” emphasizing not only athletic achievement but advocacy.

Legacy talk can drift into sentiment. But in tennis, the numbers make the point brutally: even now, Ashe remains the only Black man to have won the U.S. Open, Wimbledon, and the Australian Open singles titles. That rarity is not just about talent distribution. It is about opportunity structures—who gets coached, who gets access, who gets protected long enough to peak.

Ashe’s early story is a case study in how Black communities built their own structures when the official ones refused them. Brook Field, Ron Charity, Dr. Johnson, the ATA—this is community infrastructure disguised as sports biography.

The match, set by set: what a serve can do

If you strip away the symbolism and just watch the tennis, the 1968 final still reads as a test of nerve.

A 14–12 first set—fifteen aces in that set alone, according to TIME’s summary—signals not just power but patience. Before tiebreakers, you had to win by two games; you had to keep serving under pressure, again and again, with no procedural relief. Ashe did it. He built a lead the old way: by refusing to blink.

Okker pushed back—taking the second set, extending the match into a five-set grind. But Ashe’s pattern—serve as leverage, composure as rhythm—held long enough for the fifth set to feel less like a scramble and more like a closing argument.

When Ashe won, the victory did not arrive with the usual material reinforcement of a champion’s moment. It arrived with per diem receipts and a historic photograph.

And yet, within tennis, the win repositioned him. By the end of the year, Ashe would be ranked No. 1 in the United States by the United States Lawn Tennis Association, per TIME’s retrospective.

The sport, belatedly, had to acknowledge what Black Richmond had been told since Brook Field: this kid is special.

“I can make my protest heard by winning.”

There is a popular version of Ashe that treats him as the “acceptable” Black athlete: measured, intellectual, controlled. That version is incomplete.

Ashe became, over time, a more vocal figure on civil rights and global justice. The Smithsonian summary notes his later activism against apartheid and the ways he used his stature beyond the court. The Guardian, reviewing Citizen Ashe, describes the tension he faced between external pressure to speak and internal caution rooted in fears of backlash, especially given his upbringing in the segregated South.

But Ashe’s line—protest through winning—reveals something sharper than moderation: he believed leverage had to be earned in a country that discounts moral appeals from those it deems marginal.

In 1968, “winning” was not neutral. A Black champion in a white sport, in an open-era debut, at a moment of national racial upheaval, represented a kind of unavoidable evidence. You could argue about protest tactics, but you could not argue with the final score.

The first U.S. Open as a cultural document

The Smithsonian notes that Ashe’s 1968 semifinal against Clark Graebner inspired John McPhee’s Levels of the Game, a work that braided match narrative with social portraiture. This is worth pausing on: the match itself was good enough to produce literature. Ashe’s presence was significant enough to make tennis feel like a lens on America rather than a pastime.

That is the deeper reason his U.S. Open victory keeps returning as subject matter. It is not only a sports milestone. It is an American document: a story about who gets to enter, what it costs to stay composed, and how institutions can celebrate your triumph while rerouting your compensation.

The open era began. The money arrived. The sport modernized.

And the first champion was a Black man trained in a segregated city to behave like he belonged in spaces designed to exclude him.

What the victory required, before it ever happened

If you trace Ashe’s journey backward from Forest Hills, you realize the win depended on a chain of improbable permissions:

* A father’s job placement that put a family home inside a Black-only park with courts.

* A local coach—Ron Charity—who saw talent and invested in it.

* A “parallel” national institution—ATA—and a physician-coach—Dr. Robert Walter Johnson—who built a development system for Black players shut out elsewhere.

* A willingness, by adolescence, to leave home for better competition because Richmond’s tennis ecosystem could not sustain his trajectory.

* A scholarship and collegiate environment at UCLA that gave him elite repetition and recognition.

* Military service that did not end his competitive development, even as it layered additional constraints onto his status.

None of those are purely personal virtues. They are structural circumstances and community interventions. Ashe’s greatness is real; so is the scaffolding that made it possible.

That scaffolding is the part we often omit when we celebrate “firsts.” And when we omit it, we quietly imply that “firsts” are inevitable—when, in reality, they are engineered against resistance.

The aftermath: what a first can and cannot change

Ashe’s win did not instantly transform tennis into an equitable sport. It did not instantly fill the pipeline with Black boys from public parks. It did not dissolve the class and racial codes embedded in the game’s culture.

But it did establish an undeniable precedent: a Black man could win on tennis’s most visible American stage, even in a sport that had long acted as if Black excellence belonged elsewhere.

And it gave Ashe something he valued: a platform strong enough to carry meaning.

TIME’s retrospective describes how Zimmerman’s photos captured the ordinary and extraordinary around the win—and includes Ashe’s own framing of victory as audible protest. The Smithsonian account emphasizes the ways he saw himself as a role model for underprivileged youth and a figure who did not let tennis consume him entirely.

Ashe’s life would later include far more than Forest Hills. But the first U.S. Open win is where many of those later arcs become legible: his commitment to dignity, his evolving activism, his insistence on education, and his awareness that representation alone is insufficient without infrastructure.

In KOLUMN’s language, this is the part where the story stops being about the trophy and starts being about the system.

Because the first U.S. Open did not just crown Ashe. It exposed tennis.

It showed that the sport could modernize on paper while still keeping old hierarchies alive in practice. It showed that “open” can be a marketing term before it becomes a moral reality. And it showed that a Black man could win the match and still be asked—by policy, by culture, by the public’s selective attention—to accept less than the full reward of being champion.

The final image: a man holding two truths

The photograph we return to is simple: Ashe holding the trophy, smiling, glasses catching light. It is the smile of a man who has done the work, survived the grind, and delivered on the moment.

But behind that photograph are two truths that define his 1968 victory:

* He won, decisively, in a five-set final defined by endurance and serve dominance.

* He was not paid like a winner, because the sport’s transitional rules and amateur-era bureaucracy rerouted the money to the runner-up.

That is not merely trivia. It is the story. It is the American story inside the tennis story: achievement amid constraint, visibility without full access, a historic first that arrives with an asterisk written by institutions.

Ashe understood those dynamics early. He understood, too, that the cleanest rebuttal was excellence.

“I can make my protest heard by winning,” he said. “People don’t listen to losers.”

In 1968, at Forest Hills, the country listened—whether it wanted to or not—because Arthur Ashe would not stop serving until the argument was over.