By KOLUMN Magazine

On the afternoon of February 14, 2018, the sound arrived first—sharp cracks that students would later learn to count, not because counting helped, but because the mind tries to organize terror into something survivable. Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, in Parkland, Florida, had the ordinary architecture of late-adolescence: bright hallways, classroom doors that never seemed to close softly, the low-grade noise of teenagers practicing adulthood. Then the building turned into a lesson the country refuses to stop teaching: how quickly a normal day becomes a crime scene, how fast young bodies learn to run without looking back.

In America, we have a well-rehearsed ritual for the aftermath. We name the dead. We watch the candlelight and the fury. We send counselors, sometimes for a week, sometimes for a semester, as if trauma follows the academic calendar. We argue over doors and deputies and the moral meaning of an AR-15. We tell survivors—children, really—that resilience is a kind of civic duty.

And then, with time, we ask them to live as if what happened to them was a chapter, not a climate.

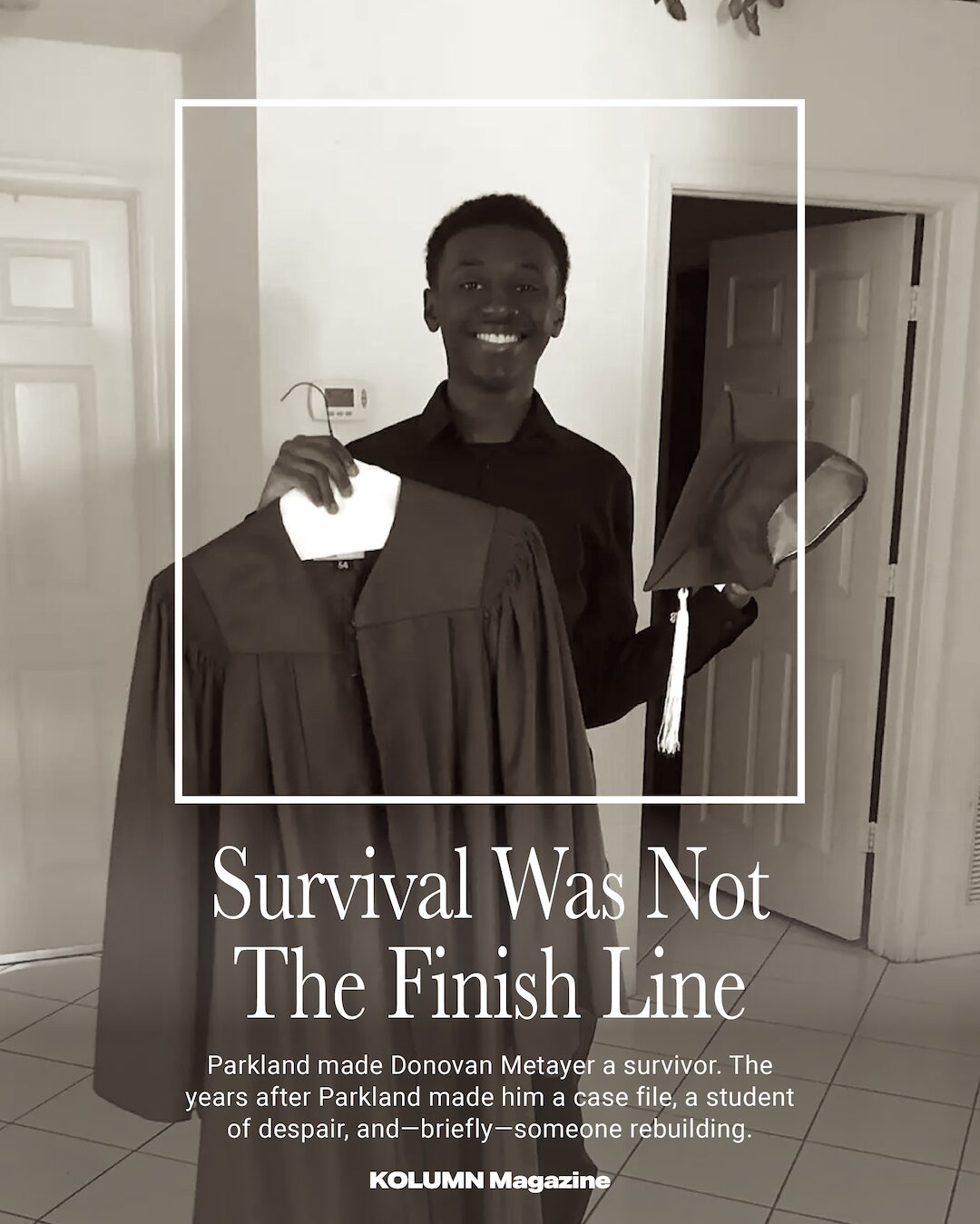

Donovan Joshua Leigh Metayer was a senior at Stoneman Douglas that day. In the years since, the country came to know Parkland through the faces of student activists, through courtroom proceedings, through anniversaries that doubled as national grief checkpoints. But Donovan’s name—until recently—was not a headline name. He was one of the many who did what survivors are expected to do: graduate, move forward, keep going. His family would later say he had been bright, warm, funny, full of plans. He dreamed of a future in computer science, and in some versions of the American story, dreams like that are the insurance policy: proof that a young person can outpace a violent past.

But surviving a mass shooting does not end when the gunfire stops. Survival, for some, becomes a long emergency—one in which the body is safe, but the mind keeps receiving the alert.

In December 2025, Donovan Metayer died by suicide at age 26, after what his family and multiple reports described as years of deteriorating mental health following Parkland, including a prolonged struggle with schizophrenia. He had been hospitalized multiple times; he had periods of stability; he earned an IT certificate and found work. He also carried something harder to credential: the private aftermath of public violence.

To tell Donovan’s life story honestly is to resist the simple narrative—the one that treats his death as an isolated tragedy, or as an inevitable consequence of a diagnosis, or as a moral about individual fragility. His story sits at the intersection of three American facts we often discuss separately, as if they were unrelated: the enduring trauma of mass shootings; the patchwork mental health system that too often routes people through crisis rather than care; and the particular barriers Black Americans face in accessing treatment that feels safe, affordable, and culturally competent.

Even now, in an era when “mental health” has become a ubiquitous phrase—spoken by athletes and CEOs, printed on school posters, hashtagged into soft abstraction—Black Americans remain less likely to receive treatment, more likely to encounter misdiagnosis and bias, and more likely to arrive at care through the worst door: the emergency door.

Donovan Metayer’s life, in other words, is not only a story about what Parkland did to one young man. It is a story about what America did—and did not build—for the people who lived.

Parkland’s second timeline

The first timeline of Parkland is the one that fits on a plaque: 17 killed, a school community shattered, a national debate re-ignited. The second timeline is longer and less ceremonial. It is measured in panic attacks, insomnia, sudden rage, numbness, dissociation—the body’s insistence on replaying what the mind is desperate to forget. It is also measured in missed appointments and insurance denials, in waitlists that stretch for months, in the difficult choreography of finding a therapist who can hold both the personal and the political, both grief and fear, without flinching.

It has become increasingly clear—through reporting on survivors and educators nationwide—that trauma is not a finite episode but a condition that can persist and evolve for years. Washington Post reporting has described how teachers return to the sites of shootings and continue teaching while managing their own symptoms, and how the population of children exposed to gun violence at school has surged in recent years. The scale itself becomes its own harm: when violence is frequent, recovery becomes provisional, always waiting for the next alert.

Another Washington Post story, published this month, follows survivors who have endured multiple mass shootings—an almost dystopian form of recurrence that is only plausible in a country where these events are common enough to overlap. The piece conveys a particular American exhaustion: the sense that there is nowhere to go to outrun the possibility of repetition.

Parkland, too, has its own history of the second timeline. In 2019, after two Parkland students died by apparent suicide, the Washington Post described a community realizing that “moving on” was not a linear process and that the trauma still lingered long after the first anniversary.

Donovan was living inside that second timeline, even if most of the country did not know it. In the immediate aftermath of Parkland, his family said, he began to withdraw. What had once been a bright, engaged teenager became someone quieter, more isolated. Over time, the suffering took on a clinical shape: hospitalizations, suicidal ideation, and, eventually, a schizophrenia diagnosis described in later reporting and in family accounts.

Schizophrenia remains one of the most misunderstood diagnoses in American public life—often flattened into caricature, often treated as synonymous with danger, despite research showing that people with serious mental illness are far more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators. Stigma attaches not only to symptoms but to the very act of seeking care. For Black families, that stigma has additional historical weight: centuries of medical racism, misdiagnosis, and coercive treatment, plus the everyday reality that many providers do not share patients’ cultural frames or understand the layered stress of being Black in America.

When a young person begins to struggle—when the world becomes loud or threatening or unreal, when sleep unravels, when paranoia sets in—the family response is often not a straight line to compassionate, continuous care. It is a relay race of phone calls, forms, and referrals. It is an argument with an insurance company. It is, sometimes, a visit to the hospital that ends with discharge paperwork and a new waitlist.

This is where Donovan’s story becomes both intimate and structural: the small daily logistics that define how a person lives with mental illness, and the larger system that determines whether those logistics are manageable or impossible.

“He was trying”: the family’s version of events

Public narratives about suicide often fail in one of two ways: they romanticize pain into poetry, or they reduce a life to a final act. Donovan’s family has tried to refuse both. In published accounts, they describe him as a “radiant” child—brilliant, warm, someone who made people laugh. They also describe a long struggle: periods of depression and guilt, repeated hospitalizations, and efforts to stabilize through therapy and medication.

There is a specific kind of heartbreak in the phrase families use when describing mental illness: we did everything we could. It is often true—and still inadequate, because “everything” is bounded by access.

According to reporting in People, Donovan received care and support through Henderson Behavioral Health (also referenced as the Henderson Clinic in other coverage) after a mental health crisis in 2021, and that relationship helped him find stability for a period. He earned an IT certificate and found employment, which for many people living with serious mental illness is not a small victory but a significant restoration of dignity and routine.

It is tempting, in stories like this, to treat that period as a turning point, a proof that treatment “worked.” A more accurate framing is that treatment sometimes works the way a scaffold works: it supports a structure under stress, but it requires maintenance, and it is vulnerable to gaps. The story of serious mental illness is often the story of continuity—of what happens when support is consistent, and what happens when it is not.

In late 2025, multiple reports describe a crucial detail: a Risk Protection Order (a civil order that can restrict firearm access for someone deemed a danger to themselves or others) had previously barred Donovan from purchasing a gun, but that order lapsed. Soon after, he obtained a handgun and died by suicide. His family has since spoken publicly about this sequence, not as spectacle, but as warning: a life can be lost not only to an illness, but to the timing of policy and the gaps between safeguards.

His family also described their desire to turn grief into something usable—raising funds not only for funeral expenses but to support mental health services for others, including the goal of creating assistance through the clinic that helped him. In the language of American healthcare, that impulse is familiar: when the system is insufficient, families build a micro-system around their loss.

But Donovan’s story, particularly because he was Black, raises an additional question: what does it mean to search for mental health care in a community where trust has been historically violated, where provider diversity is limited, where the cost of care competes with rent and groceries, and where the cultural script still too often says: keep it to yourself?

The treatment gap Black America keeps naming

There are statistics that should change the way this country talks about mental health, but often do not. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health notes that in 2023, suicide was the third leading cause of death for Black or African Americans ages 15 to 34—an age span that includes the cohort that lived through Parkland and is now aging into adulthood.

The same federal resource describes persistent disparities in treatment rates—differences that reflect access, affordability, and the long tail of stigma.

NAMI, in its guidance on mental health in Black communities, emphasizes another stark framing: despite need, only a fraction of Black adults with mental illness receive treatment, and many face barriers including provider bias and cultural incompetence that can lead to misdiagnosis or inadequate care, reinforcing mistrust.

The Kaiser Family Foundation has also reported on disparities in mental health care and on how discrimination and racism shape experiences with the healthcare system, affecting both willingness to seek care and the quality of care received.

Stigma is often described as a cultural issue—something inside families or churches, something whispered or denied. But stigma is also structural: it is produced and reinforced when the most visible pathway to help is involuntary hospitalization, police involvement, or a hurried emergency-room evaluation. If the only care you see is crisis care, you learn to associate treatment with danger, shame, or punishment.

A set of research and professional literature has long described how stigma and social support shape depressive symptoms among African American adolescents, and how interventions must account for cultural context.

And then there is the workforce problem: if you cannot find a provider who looks like you—or, more importantly, who understands you—care can feel like translation work done while bleeding. The University of Michigan School of Public Health has noted that only a small fraction of psychologists in the United States are Black (often cited at roughly 4%), a shortage shaped by financial and institutional barriers across the training pipeline.

This is the backdrop against which Donovan’s family sought help: not only the universal difficulty of navigating American mental health care, but also the specific experience of being Black within it.

Parkland and the private cost of public violence

Mass shootings create a kind of social afterimage: the horror is collectively consumed, replayed, debated, packaged into documentary form, used as argument in elections. Survivors live with the private cost.

There is a particular cruelty in how the country tends to frame survivors. We praise them when they become symbols: activists, valedictorians, resilient success stories. We pay less attention when survival looks like a quieter struggle—when it looks like missing class, losing friendships, gaining weight on medication, failing a semester, waking up terrified without knowing why. When the costs are invisible, support becomes optional.

Donovan did not become a national spokesperson. His life after Parkland—at least in the public record—was not a series of televised speeches but the long work of trying to stay afloat: treatment, crisis episodes, recovery attempts, and the pursuit of ordinary milestones.

There is, in that ordinariness, an argument about what we owe survivors. If the country’s primary response to mass shootings is to harden schools and hold vigils, then we have misunderstood the problem. The crisis does not end when the shooter is sentenced. It does not end when the building is demolished or preserved. It continues in the nervous systems of the living.

Washington Post reporting on Parkland’s longer arc—its anniversaries, its later deaths, its expanding awareness of trauma—points to a reality that mental health professionals have been naming for years: trauma is not solved by time alone. It is metabolized, or it is not. And “metabolized” requires support—consistent, accessible, long-term support.

Why “availability” is more than a directory

When people talk about mental health access, they often imagine a simple obstacle: not enough clinics, not enough therapists, not enough money. Those are real. But “availability” in the Black American community is also about whether care feels safe enough to enter.

Consider the layers:

Cost and coverage. Therapy is expensive. Psychiatry can be expensive. Medication can be expensive. Even with insurance, deductibles and copays can make weekly care impossible. If you are juggling family obligations, work schedules, transportation, and the administrative tasks of staying insured, mental health care can become a luxury item.

Provider scarcity and mismatch. In many places, there are not enough psychiatrists. There are not enough therapists. And when there are providers, there may not be many who specialize in trauma, psychosis, or culturally responsive care. The mismatch becomes its own barrier: telling your story repeatedly to clinicians who do not understand you can feel like being retraumatized by the system.

Stigma and historical memory. Stigma is not merely embarrassment; it is sometimes a rational response to a history in which Black pain has been dismissed, pathologized, or weaponized. NAMI’s resource on Black mental health explicitly notes the role of prejudice and discrimination in shaping negative experiences with treatment, contributing to mistrust and avoidance.

Crisis pathways. When care is not available early, people arrive late—often in crisis. That means hospitalization, law enforcement interaction, or a sudden medicalized moment that feels like loss of control. Crisis care can be necessary, but when it becomes the default entry point, it teaches families to fear the system.

These dynamics are visible not only in the U.S. but across other systems. Reporting in The Guardian on racial inequities in mental health services (in the UK context) underscores how minority communities can face longer waits and worse outcomes—an international echo of a shared pattern: marginalized people reach care later and receive less effective support.

In the U.S., Black-led and Black-focused organizations have spent years building alternative routes to care—directories, microgrants, voucher programs, culturally grounded peer support. Word In Black has highlighted free resources and organizations like BEAM, the Boris Lawrence Henson Foundation, and the Loveland Foundation, which exist largely because mainstream systems have not met the need.

This is not charity as a lifestyle brand. It is a corrective.

The unspoken work families do

If you want to understand mental health access in America, you can do worse than to follow the paper trail: intake forms, insurance authorizations, appointment reminders, discharge summaries. But the real story is often in the unrecorded labor of families.

Families become care coordinators. They learn the vocabulary—“inpatient,” “outpatient,” “partial hospitalization,” “case management,” “med compliance,” “suicidal ideation”—as if they are studying for a degree they never wanted. They create safety plans and monitor sleep. They negotiate with adult children who want autonomy but cannot always safely manage it. They make decisions under pressure, often without guidance that feels trustworthy.

For Black families, this work can be complicated by additional concerns: Will my loved one be treated with suspicion? Will crisis care involve police? Will a provider see my child as dangerous rather than sick? Will the system interpret our grief as aggression?

These concerns are not theoretical. They are shaped by the broader experience of discrimination and bias in healthcare settings, documented by organizations like KFF and discussed in resources focused on Black mental health care.

Donovan’s family, in public statements and in the very fact of their fundraising, has suggested something familiar to many caregivers: even when you find a clinic that helps, the help can be fragile—dependent on the continuity of appointments, insurance coverage, stable housing, stable routines, and a healthcare system not built for long-term relational care.

When care works—briefly, importantly

It matters to say clearly: care can help. Donovan’s story includes periods of stability, including support through a behavioral health clinic, educational progress, and employment. Those are not footnotes; they are evidence.

But those improvements also reveal the problem with how America narrates mental health: we treat recovery as a finish line rather than a management process. People with chronic conditions do not “graduate” from care. They live with a condition, and care helps them live.

The question, then, is not whether Donovan “did the work.” By accounts from his family, he did. The question is whether the system did the work with him—reliably, continuously, with the safeguards and follow-through that a person with severe illness and trauma exposure requires.

In public health terms, this is the difference between episodic care and continuity of care. In human terms, it is the difference between being held and being dropped.

Black mental health, and the tyranny of the exceptional

In the past decade, there has been a welcome shift in public conversation about Black mental health. Organizations, public figures, and journalists have pushed the topic into the open. Word In Black has reported on advocacy efforts and programs aimed at young Black adults and students, including campus-focused initiatives and community-based approaches.

The Root has published essays and commentary urging the dismantling of stigma and describing how fear, medication, and access intersect in Black communities.

But there is a risk in the “visibility” era: we can start to believe that conversation equals infrastructure. It does not.

One way this shows up is in the tyranny of the exceptional—celebrating the rare person who finds a perfect therapist, the family that can pay out of pocket, the celebrity who can hire a private team. Most people do not live there. Most people live with the slow friction of scarcity.

Another way it shows up is in how we frame suicide in Black communities—as an aberration, as “surprising,” as something that happens elsewhere. Yet federal data and public health reporting have made clear that suicide is a serious and growing concern among Black youth and young adults.

Donovan’s life forces us to retire the comforting myths. Black people do experience suicidal despair. Black families do seek help. And Black people, too, can be lost—not because they did not try, but because the systems designed to catch them have holes.

The shape of stigma: what it looks like up close

Stigma is often portrayed as a simple refusal: we don’t believe in therapy. In reality, stigma is more complex, and often braided with legitimate skepticism.

Professional counseling literature has described how mistrust, lack of representation among providers, and cultural distance contribute to reluctance in seeking care, and how the scarcity of Black mental health professionals intensifies that gap.

Stigma is also produced by messaging that equates strength with silence. In some households, discussing mental illness is feared as an invitation for judgment—or as a threat to employment, custody, or social standing. In some churches, prayer is offered as the first line of support, sometimes as the only line. Faith and therapy are not inherently in conflict, but when mental illness is moralized, people suffer in isolation.

And then there is the stigma of diagnosis itself. Schizophrenia, in particular, carries public fear. Families can be reluctant to name it, even to relatives. Patients can internalize shame, resisting treatment not because they deny symptoms but because they understand what the label can cost them.

Donovan’s family, by speaking openly, has taken a risk that many families avoid: public honesty. That openness is itself an intervention, a refusal of silence as a default.

Gun violence, mental illness, and the policy gaps in between

Any story that includes both gun violence and mental illness is vulnerable to distortion. The most common distortion is the implication that mental illness causes mass shootings. In fact, the relationship between mental illness and violence is complex, and people with serious mental illness are far more likely to be harmed than to harm others. The more urgent and consistent association in the U.S. is between gun access and gun death.

Donovan’s case, as reported, highlights a different and less discussed linkage: the intersection of self-harm risk and firearm availability, particularly when legal safeguards are temporary or expire without a durable care plan.

Risk Protection Orders—often called “red flag” laws—are designed to create time and distance during moments of acute risk. But time is only useful if it is filled with effective care, stable monitoring, and meaningful support. When an order expires, what then? The question is not only legal. It is clinical, social, and logistical.

Reporting has described that Donovan’s Risk Protection Order lapsed, after which he obtained a handgun and died by suicide. That sequence has prompted renewed attention to how protective measures work in practice—how they are maintained, renewed, or allowed to end—and what supports are available when they do.

To treat this as a purely legal story—paperwork filed, paperwork expired—is to misunderstand the lived reality. A person with severe mental illness does not experience stability as a permanent state. They experience it as something that must be defended, often daily, against relapse, stress, and the long echoes of trauma.

The clinic as a lifeline—and a case study

Community behavioral health clinics are often the backbone of mental health care for people who cannot pay private rates. They offer sliding scales, case management, medication support, and sometimes crisis stabilization. They also operate under chronic strain: staffing shortages, high caseloads, limited appointment availability, and the difficult task of serving patients with complex needs in a fragmented healthcare ecosystem.

In Donovan’s story, the Henderson clinic is described as a source of stability after a crisis. His family’s desire to establish a fund connected to that clinic suggests both gratitude and recognition: this is where care actually happens, where lives can be held together.

But clinics cannot be asked to do the impossible. If a community has more need than providers, people will still fall through.

And in Black communities, the need is amplified by layers of trauma: direct violence exposure, racial discrimination, economic stress, and intergenerational burdens that are rarely fully captured in diagnostic checklists.

What “culturally competent” care actually means

The phrase “culturally competent” is often used as a slogan. In practice, it means something more specific and more demanding:

A provider who understands how racism functions as stress, not as an abstract concept but as a daily physiological reality.

A provider who does not default to stereotypes—anger as “aggression,” grief as “noncompliance,” guardedness as “paranoia.”

A system that does not penalize patients for being late when transportation is unreliable or work schedules are unstable.

A care plan that accounts for family, faith, and community structures—not in a patronizing way, but as real components of support.

Word In Black’s coverage of mental health initiatives and resource lists reflects a practical recognition: people often search for providers who can understand them without forcing them to translate their lives.

The shortage of Black providers makes this difficult, and the result is predictable: many people delay care until symptoms worsen, increasing the likelihood of crisis entry points.

Donovan’s life as a mirror

Donovan Metayer’s story is, at one level, singular: one young man, one family, one set of memories. It is also representative in ways that should be uncomfortable.

It reflects what happens when a national trauma becomes a private diagnosis. It reflects what happens when a school shooting ends on television but continues in a household. It reflects what happens when the infrastructure of care is uneven—when the ability to find treatment depends on zip code, insurance status, and the luck of the referral.

It also reflects a particular American habit: we build memorials faster than we build systems.

We can trace this habit in the way survivors are treated. In the first months after Parkland, attention and resources flowed. Over years, attention thinned. But the needs did not. Washington Post reporting on the long-term trauma of school shooting communities underscores that recovery is not a short-term project; it is a long-term obligation.

Donovan lived long enough to become an adult survivor—a category that has far less cultural support than “student survivor.” Adult survivors are expected to work, to date, to perform competence. When they struggle, the struggle is often interpreted as personal failure rather than predictable aftermath.

And for Black survivors, the expectation of competence can be even more rigid, shaped by the “strong Black” myth and by a society that punishes visible vulnerability. The result can be a double-bind: seek help and risk stigma; avoid help and risk collapse.

The question his death leaves behind

There is a cruel tendency in public discussion of suicide to look for a single cause—one moment, one trigger, one failure. Families know better. Suicide is often the end stage of accumulation: symptoms, stressors, gaps in care, moments of fear, moments of isolation, moments when the future feels unreachable.

Donovan’s family has described a long struggle. Reporting has described schizophrenia and trauma, hospitalizations and treatment, stability and relapse, protection and vulnerability.

If his life teaches anything, it is that “awareness” is not enough. Awareness does not shorten waitlists. It does not diversify the workforce. It does not make therapy affordable. It does not ensure continuity of care when legal protections expire. It does not guarantee that a young Black man will feel safe telling a clinician the truth about what he is hearing, fearing, or thinking.

Awareness, without infrastructure, is a form of performance.

What would infrastructure look like?

Long-term, trauma-informed services for mass-shooting survivors, not limited to immediate crisis counseling.

Sustained funding for community behavioral health clinics, with staffing models that reduce churn and burnout.

Workforce pipeline investments that increase the number of Black psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, and counselors.

Culturally responsive care standards that are enforced, not merely suggested.

Suicide prevention strategies that treat firearm access as a public health issue, including careful attention to what happens when protective orders end.

Community-rooted supports—peer groups, church-based counseling partnerships, and culturally specific organizations—integrated into formal systems rather than treated as informal substitutes.

None of this would guarantee that every life is saved. But it would mean fewer families doing the impossible alone.

A final note, and what to do if you need help

Donovan Metayer’s family chose to speak openly about his death. Their choice carries a difficult hope: that telling the truth might interrupt another loss.

If you or someone you know is struggling or thinking about suicide, help is available in the United States by calling or texting 988, the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, which operates 24/7. (If you are outside the U.S., local crisis lines are available in many countries.)