KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

The first thing you notice, if you’ve never stood close enough to feel it, is that Double Dutch is louder than you expect. Not loud in the way a basketball gym is loud—no sneaker squeaks, no whistle, no coach’s bark—but loud with percussion: rope striking floor, rope striking air, rope striking the moment between one decision and the next. The sound is steady until it isn’t. A turner adjusts by a half-inch, a jumper waits a half-beat longer than instinct suggests, and suddenly the ropes produce a new rhythm, a sharper one, like a drummer switching sticks mid-song.

At the highest levels, the ropes become a kind of clock. They tell you whether you’re late, early, hesitating, or lying to yourself about your readiness. The most important skill, old heads will tell you, isn’t the flip or the back-scratch or the release. It’s entry. Entry is the whole theology of Double Dutch: the capacity to watch something moving fast and decide, with calm certainty, that there is room for you inside it.

That capacity—practical, physical, metaphoric—helps explain why Double Dutch has traveled the distance it has. A game that many Americans remember as a neighborhood pastime, especially associated with Black girls in larger cities, now operates as a serious competitive sport with leagues, judging criteria, training pipelines, and international contenders. The National Double Dutch League (NDDL), one of the most visible institutions in the sport’s modern era, traces its roots to the early 1970s formalization of rules by David A. Walker and Ulysses Williams, two NYPD officers who recognized what Black children had already built on sidewalks and in schoolyards: a complex athletic culture hiding in plain sight.

There is a familiar American pattern here: something invented or refined in Black communities becomes, first, a symbol; then a commodity; then a discipline; then, finally, an export. But Double Dutch has always resisted flattening. It is too collaborative to be reduced to a single star. Too musical to be treated as mere conditioning. Too strict about timing to be faked. It demands that you live in the present tense.

And it has never been only about jumping.

The Old Argument About Origins—And The Truer One

“Double Dutch” as a phrase existed long before it became the name of a sport; English speakers used it to mean speech that sounded like nonsense, an old insult aimed at the perceived strangeness of Dutch language. Merriam-Webster records the phrase’s earlier meaning as “unintelligible language,” alongside its later definition as the jump-rope game.

Because the term feels like it should have a literal genealogy—Dutch settlers, New Amsterdam, old-world children’s games—some accounts try to root the practice in the Netherlands and ferry it neatly across the Atlantic. You will find modern retellings that emphasize that story, in part because it offers the comfort of a tidy origin.

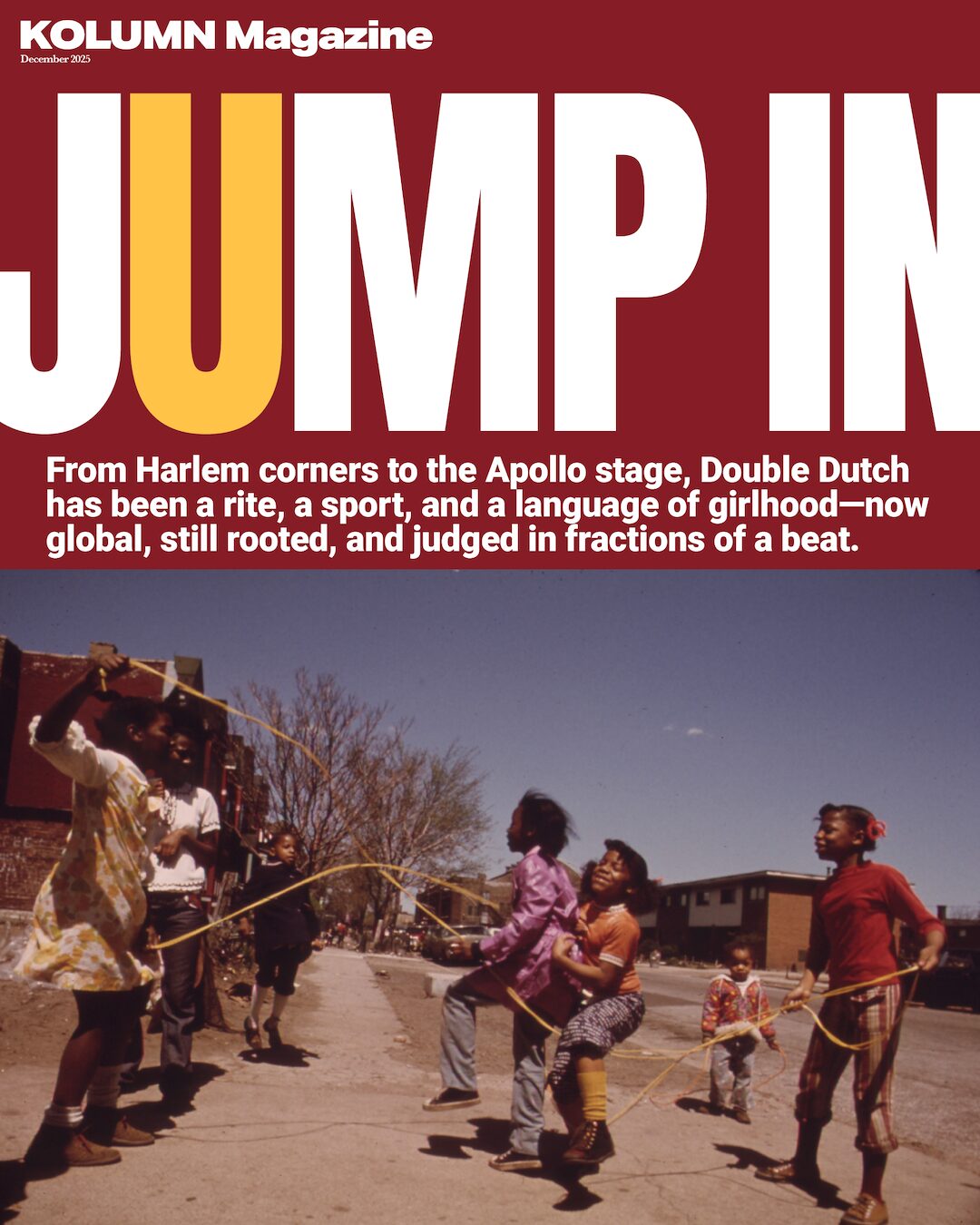

But the more meaningful origin story—the one that matters if you’re trying to understand Double Dutch as it lives in American memory—has less to do with the name and more to do with the neighborhood. Multiple historical summaries of the sport’s modern form place its development squarely in Black urban communities in the mid-20th century, where girls repurposed clotheslines and jump ropes, gathered on corners, and invented steps, chants, and styles that were both game and performance.

By the time Walker and Williams began codifying rules and organizing competitions, they weren’t inventing Double Dutch so much as translating it—moving a street art into a format legible to schools, sponsors, and civic institutions. Accounts of that moment describe them creating a rulebook and borrowing elements from other sports: compulsory moves, speed tests, freestyle routines.

The translation mattered. It gave Double Dutch a public stage and a competitive grammar. It also introduced a new tension that still defines the sport: the push and pull between what’s most alive in the street—improvisation, swagger, inside jokes—and what’s most rewarded in formal competition—precision, difficulty, repeatability.

Harlem, 1974: When The Sidewalk Got a Scoreboard

One way to picture the leap from street to institution is to time-travel to the early competitions in New York City, when Double Dutch briefly occupied a civic spotlight that now seems improbable: young jumpers becoming neighborhood celebrities, adults treating rope skills as a legitimate athletic subject, the city itself acting like it had discovered a local marvel.

A 1974 New Yorker “Talk of the Town” piece describes attending New York’s first Double Dutch championship finals at an intermediate school in Harlem, introducing readers to the competitors and their routines with the tone of someone realizing, mid-reporting, that the children’s game he thought he understood was actually an advanced discipline.

In these early portraits, you can see the sport’s enduring ingredients: the seriousness beneath the play; the way jumpers narrate their own skill; the way turners, often treated as background by outsiders, are in fact co-authors of every successful trick. The ropes are not equipment in the way a bat is equipment. They are collaborators. If they do not trust you, you will not survive the routine.

It’s also clear that Double Dutch was never just physical. The chants—the songs timed to entries and exits—operated as memory devices and cultural transmission, passing phrases and cadences between kids the way dance crews trade counts. The sport carried oral tradition in the same breath as athletic instruction. The sidewalk was a rehearsal studio and a social forum.

A Rite, a Refuge, a Rehearsal for Life

Ask almost anyone who grew up around Double Dutch in a Black neighborhood and you’ll hear the same paradox: it looked casual, but it ran on rules.

There were rules about who got to turn, who got to jump, who was allowed to step in without permission, who was trusted to speed up the ropes for a difficult routine. There were rules about pride, too—how you handled missing a step, how quickly you got out of the way, how you talked about someone else’s skill. Double Dutch trained the body, but it also trained temperament.

It served, for many Black girls especially, as a public space that belonged to them. A game you could start with three people and a couple of ropes created a social geometry in which girls set the terms. The street corner became a stage where style and athleticism weren’t competing values; they were the same value. To be good was to be both correct and creative.

In an era when youth sports often act as pipelines—toward scholarships, travel teams, professional dreams—Double Dutch offered something different: a way to be excellent without needing institutional permission. You didn’t need a field reservation. You needed rhythm, stamina, and community. This is why the game held on so tightly in many Black urban environments through the 1940s, 50s, and beyond—and why later efforts to formalize it could claim, plausibly, that they were elevating something already elite.

For the adults who watched, it was also a kind of reassurance. Here was disciplined play in a world that often stereotyped Black children as unruly. Here was cooperation, timed down to the millisecond. Here was strength training disguised as fun. Double Dutch made athletic virtue visible—without asking permission from mainstream gatekeepers.

The emotional technology of entry

If Double Dutch has a single psychological lesson, it’s the practice of entry under pressure.

You cannot enter the ropes by force. You cannot enter by wishing. You enter by reading a moving system accurately and committing fully to a moment that will not pause for you. That lesson—how to join the turning world, how to trust your timing, how to accept consequences instantly—lands differently depending on the life you’re living.

This is why Double Dutch remains so potent as metaphor in Black storytelling: it captures what it feels like to approach opportunity and danger at the same time, to hover at the edge until you find the opening, to know that hesitation will cost you. Even when the word appears in writing far from a playground, it often carries that meaning—risk, timing, the courage to step in.

When Double Dutch Met Hip-Hop: Shared Cadence, Shared Politics of Style

Double Dutch is not hip-hop, but it has long been adjacent to hip-hop’s earliest ecosystem: the street as venue, the body as instrument, the cypher-like circle of spectators, the premium placed on originality.

By the early 1980s, Double Dutch was strongly associated with New York hip-hop culture, and it appeared in music and media that treated it as shorthand for an urban Black aesthetic: Frankie Smith’s “Double Dutch Bus,” Malcolm McLaren’s “Double Dutch,” later films like Disney’s Jump In! that attempted to translate the sport for a wider audience.

The deeper overlap, though, is structural. Both hip-hop and Double Dutch are about improvisation inside constraint. The ropes impose a grid the way a beat imposes a grid. Within that grid, you can either repeat what’s been done before or invent something that makes the spectators step back.

In competition, especially in “fusion” formats where routines integrate music and dance, you can see Double Dutch operating as a performance art as much as sport—an athletic choreography that can borrow from breaking, footwork, and contemporary dance without losing its own core identity. The ropes remain the truth test. They don’t care how fashionable your move is. They care whether it lands.

From Civic Pastime to Organized Sport

Today, competitive Double Dutch is anchored by a small constellation of organizations and events, with the NDDL’s Holiday Classic among the most prominent annual gatherings. The NDDL describes its origin story through David A. Walker’s formation of early governing bodies beginning in 1974, and it positions itself as a steward of a sport that moved from street game to world-class competition.

The Holiday Classic, staged in recent years at iconic venues like Harlem’s Apollo Theater, packages the sport as a cultural event—awards, performance, spectacle—while still insisting on judging, rankings, and champions.

If you want to understand how Double Dutch feels in this mode—how it looks when a street tradition becomes a ticketed production—consider a fashion-and-culture dispatch that covered the 2024 NDDL competition with the attentive gaze usually reserved for runway: the crowd, the styles, the sense that the theater is not replacing the street so much as borrowing its energy and giving it new lighting.

And if you want to understand the way old legends still matter, consider how contemporary competitions treat former champions not as retired athletes but as elders—people whose bodies once proved what was possible, whose presence still carries the authority of having mastered entry and flight. A report on the Double Dutch Summer Classic’s return to Lincoln Center in 2017—after decades away from that particular stage—frames the event as both revival and homecoming, a reminder that Double Dutch once occupied a highly visible place in New York’s public culture.

What the Ropes Did for People

A longform history risks becoming a parade of dates and institutions unless you stay close to what Double Dutch actually produces in human lives: identity, endurance, friendship, a durable sense of competence.

One of the most revealing recent portraits comes from Washington, D.C., where a wave of women—many over 40—have returned to Double Dutch not to compete for national titles but to reclaim something they associate with joy, community, and self-recognition. A Washington Post feature describes the scene with affectionate realism: adults laughing as they miss their timing, trying again, building a “double-Dutch sisterhood” around a game they thought they’d outgrown.

This is not nostalgia as museum. It is nostalgia as physical practice. Your body remembers, until it doesn’t—and then you teach it again.

The sport also remains a family enterprise in many places. An Ebony feature on the Walker family frames the NDDL not just as an institution but as a generational project—Double Dutch as legacy work, preserved through events that create space for young Black girls to be witnessed and celebrated.

What emerges from these narratives is a kind of understated social infrastructure: Double Dutch as an alternative institution that teaches teamwork with unusual intensity. Most sports divide labor—one person shoots, another rebounds, another defends. Double Dutch requires simultaneous mutual responsibility. If a turner speeds up without warning, she can sabotage a jumper’s routine. If a jumper rushes entry, she can destroy the rope pattern. Success demands not just skill but trust.

The hidden brilliance of the turners

To the untrained eye, competitions can look like a blur: two ropes, fast feet, sudden flips. But within the sport, roles are explicit.

At minimum, Double Dutch requires two turners and one jumper; many routines use two jumpers. Competitive formats often include categories that blend speed and freestyle, as well as compulsory elements—required moves performed under standardized expectations. Historical summaries of organized competition describe exactly this structure: compulsory tricks, speed testing, freestyle performance.

Turners, especially, are underestimated by newcomers. They are not simply rotating ropes. They are maintaining consistent rope geometry—height, tension, speed, spacing—while also handling transitions that can include releases, switches, and moments when the ropes themselves become props. One turner’s fatigue becomes everyone’s problem. A routine is only as stable as the turners’ discipline.

This is why elite teams often talk about turning the way musicians talk about timekeeping. It’s not background. It’s the beat.

National Competitions—and the Champions Who Keep Rewriting the Map

National competition” in Double Dutch is both literal and complicated. Some events are national in the sense that U.S. teams dominate the field; others are national in the sense that an American organization convenes teams from many countries, turning “national” into “international by invitation.”

The NDDL’s Holiday Classic is one of the clearest examples of the latter: a marquee competition that reliably draws elite teams from the United States and abroad. The published results from recent years make the sport’s globalization unmistakable.

2024 NDDL Double Dutch Holiday Classic: the podium goes global

In the 2024 results, the top placements include teams from Japan and Guinea alongside U.S. contenders. The first-place team listed is Yesman (Osaka, Japan), followed by Guinea Jumps for Jerry 2 (Guinea, Africa), with additional top placements including Showmen Toppers (Kyoto, Japan) and No Logic (Tokyo, Japan).

Down the list, U.S. teams appear with strong showings—Charlotte, North Carolina; Maplewood, New Jersey; Greenbelt, Maryland—underscoring that the sport’s roots remain domestic even as its talent pipeline is now undeniably global.

2023 NDDL Double Dutch Holiday Classic: U.S. teams on top

The 2023 results page lists Bouncing Bulldogs Blue (Chapel Hill, North Carolina) in first place, with Millennium Collection (Tokyo, Japan) in second—another snapshot of a competitive landscape where U.S. and Japanese teams routinely trade supremacy.

The event as institution: why the Holiday Classic matters

Beyond winners, the Holiday Classic functions as an annual convening—part championship, part cultural gathering—hosted in spaces that carry Black performance history, including Harlem’s Apollo.

And it is not alone. Other tournaments—regional leagues, local circuits, invitational events—have expanded the sport’s footprint. A 2025 photo report from Albany describes teams traveling from around the country for a “Sky’s the Limit” tournament hosted by a local Double Dutch league, evidence of a wider ecosystem beyond the marquee Harlem event.

This isn’t decline. It’s evolution—and, like any evolution, it comes with tradeoffs.

Double Dutch as Education: What it Teaches that School Rarely Does

For many Black girls, Double Dutch was one of the earliest arenas where excellence was visible and social. You weren’t excellent in private; you were excellent with an audience—friends, neighbors, rivals, kids leaning on fences. That taught performance, yes, but it also taught composure: how to miss and recover without collapsing, how to keep your face steady while your lungs burn.

It also taught an unusual kind of leadership. Turners lead without appearing to. They set tempo, regulate difficulty, and decide who is safe to enter. They learn to be accountable to others in a way that resembles adult project management more than it resembles playground play. The jumper—often treated as star—learns humility fast. The ropes do not negotiate.

This is why Double Dutch has remained meaningful even for those who never competed. It is a portable school of timing and trust.

The Future: Olympic Dreams, Global Rivals, and the Stubborn Power of the Corner

There have been periodic pushes to position rope skipping disciplines for broader international recognition, including Olympic inclusion efforts in the wider jump rope world; Double Dutch often appears as a central discipline within that ecosystem.

Whether or not Olympic recognition arrives, the sport’s future is already being written in its competitive data: Japan’s consistent dominance in top placements; African teams appearing on major podiums; U.S. teams continuing to produce champions out of community programs and school-based training.

But the deeper future question is cultural, not institutional: can Double Dutch keep its roots intact while it grows?

The answer may depend on whether the sport continues to honor the thing it was before it was ever scored: a collective performance that turned the sidewalk into a stage for Black girlhood—one where athletic intelligence was assumed, not doubted; where style was not decoration but proof; where the hardest part was not flipping in the air but deciding you belonged inside the ropes.

Because Double Dutch, in the end, is still an argument about entry. About reading the moving world and stepping into it without apology.

And every time someone stands at the edge, watching the ropes turn, knees dipping with the old instinct, the sport renews its oldest promise: there is room, if you can find the beat.