By KOLUMN Magazine

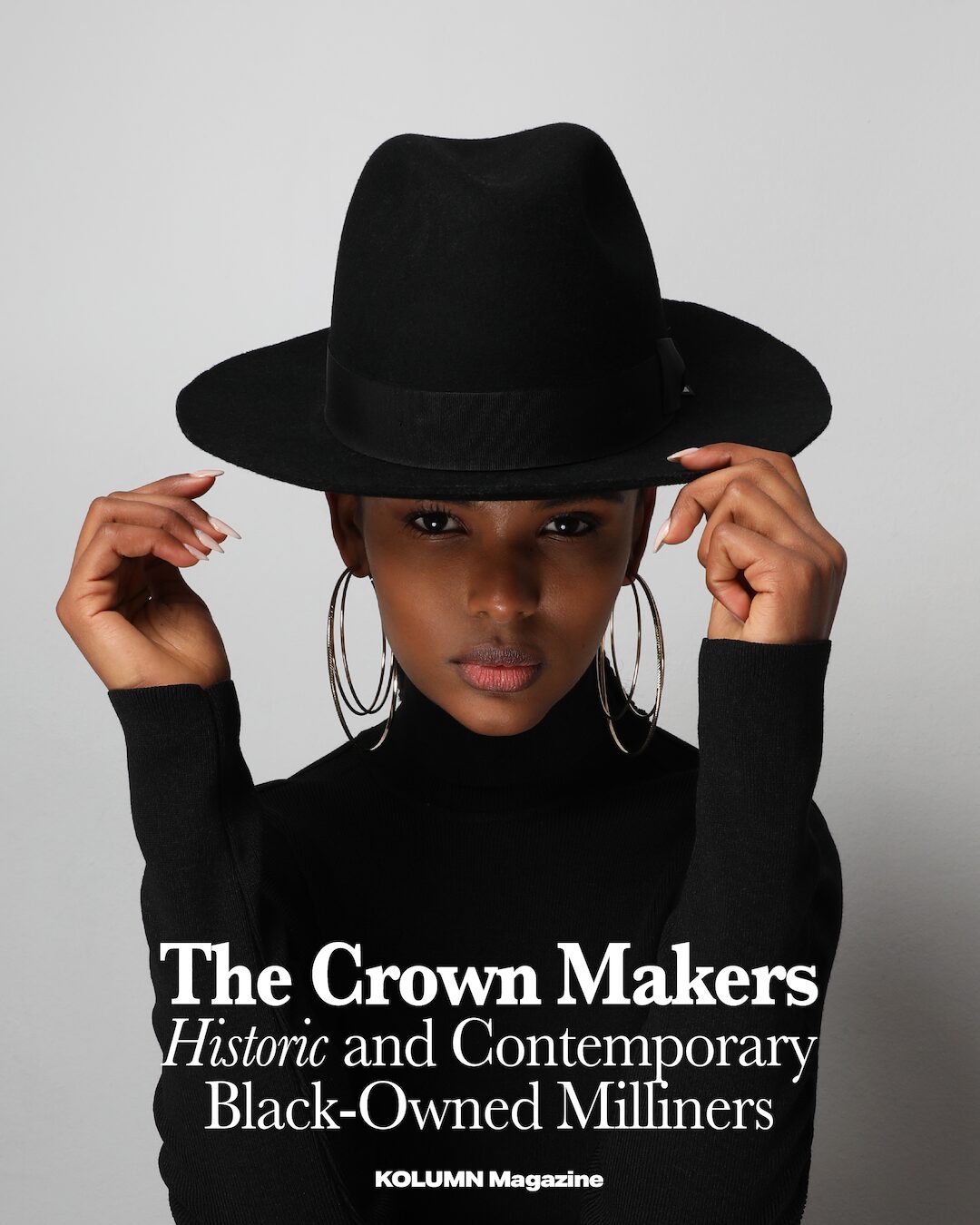

On certain Sundays in Black America, a hat is not an accessory so much as an announcement.

It enters the room a half-second before the wearer—wide brim first, then the ribbon’s quiet logic, then the feather that seems to have been persuaded into place rather than attached. In the best examples, the hat does what architecture does: it directs attention, establishes scale, implies ceremony. The body becomes a building. The aisle becomes a runway. And for a few hours, in sanctuaries and fellowship halls and repurposed storefronts, the world’s hierarchy feels rearranged.

That rearranging has always been part of the Black milliner’s work. The popular story of American fashion still tends to treat hats as a seasonal flourish—here for Easter, gone by summer—or as a quaint relic from the era when men wore fedoras to work and women wore pillboxes to lunch. But in the places where Black milliners have made their living, hats have been a persistent technology: of self-definition, of respectability politics navigated and subverted, of grief ritualized, of joy engineered.

And, crucially, of entrepreneurship.

Because the hat business—unlike most mythologies about glamour—has always been about money: who can borrow it, who can lease space, who can buy felt in bulk, who can afford to stock trims that might not sell for months, who can withstand a slow season. Millinery is art, but it is also inventory management and customer acquisition and—particularly for Black women and men who were denied easy access to mainstream credit—creative finance.

Consider Mae Reeves, whose story reads like a parable about both style and the American banking system. She secured a $500 loan from a Black-owned bank—Citizens and Southern Bank—in her own name, and opened Mae’s Millinery Shop in Philadelphia, a move that made her one of the first Black women to own a business in the city’s downtown commercial life. The hats mattered, but so did the signature on the loan. The brim, in this sense, was also a deed.

Or Mildred Blount, who began as an errand girl and became, through talent and refusal, a milliner to Hollywood and a barrier-breaker in the museum world—someone who forced the question of who gets to be considered an artist when the work is “fashion.”

Or Toni Ham, a Tucson milliner whose hats—bright, ornate, church-born—circulated far beyond her studio, showing up on heads that wanted color and uplift, and whose legacy now travels through family and community festivals like an heirloom business plan.

Across decades and geographies, and now into a new wave of Black-owned millinery—from Frances Grey’s sculptural restraint to Harlem’s Heaven Hats, from the street-ready fedoras of TomGFashion to the brim-forward identity project of House of Brims—these businesses argue for hats as living culture, not costume. They also reveal the practical genius behind beauty: sourcing, pricing, branding, and the intimate, repeat-customer economy of people who come back not just for another hat, but for the feeling it gave them the first time.

The brim, once you start looking, is everywhere.

The American Hat as Black Invention of Meaning

A hat can be made in a day. A tradition takes longer.

In Black communities, headwear has carried multiple, sometimes conflicting assignments: to signal taste, to meet a dress code, to defy one, to mark membership in a social class, to claim adulthood, to broadcast mourning without speaking, to speak without permission. The “church hat” is the most visible symbol, but it is only one branch of the family tree.

The endurance of Black millinery is partly explained by ritual. There are moments—Easter, Mother’s Day, homecomings, funerals—when a hat becomes less optional than expected. But it also endures because the hat does something uniquely suited to the pressures of being watched: it directs the gaze. It gives the wearer authorship over what a stranger notices first.

That is why millinery, for so long, functioned as both craft and counseling. A milliner does not simply sell; she interprets. She measures a head the way a tailor measures a shoulder: with an eye for proportion, but also for story. She asks the soft questions that are not really about fashion. Where are you going? Who will be there? How do you want to be seen?

The answers—spoken or not—determine everything: brim width, crown height, the angle a hat will sit when you turn your face toward light. In the hands of a great milliner, the hat becomes a controlled narrative.

That narrative control was never trivial for Black Americans whose bodies were politicized and policed. If the world insisted on reading Blackness as a problem, a hat could be a rebuttal. Not a naive one—no accessory defeats structural racism—but a daily strategy: I decide what you see when you look at me.

In the 20th century, Black milliners turned that strategy into businesses that served neighborhoods the way barbershops and beauty salons did: as aesthetic infrastructure. The shop was a place to be fitted, yes. It was also a place to be recognized.

That is where the modern story begins: not on a runway, but in storefronts—Philadelphia, New York, Los Angeles, Tucson—where hats were made for customers whose names might never appear in fashion history, but whose money and loyalty kept the craft alive.

Mae Reeves and the Loan That Became a Landmark

The common version of entrepreneurship celebrates risk, but rarely specifies the terms of risk—interest rates, collateral, the quiet humiliations of being denied.

Mae Reeves’s legend, preserved now in museum displays and community remembrance, is unusually concrete about the financial mechanism that made her artistry possible: she obtained a $500 loan from Citizens and Southern Bank, a Black-owned institution, and used it to open Mae’s Millinery Shop on South Street in Philadelphia.

Five hundred dollars is not an epic sum in the modern imagination. But the number matters precisely because it is small enough to reveal how narrow the gate could be: a modest loan, in the right hands, could seed a business that would shape a neighborhood for decades. The point is not just that Reeves was talented; it is that credit—so often withheld—arrived, and she converted it into permanence.

Reeves had trained and worked in the apparel industry before opening her own shop, learning not only how to construct hats but how a city’s fashion economy works: which fabrics move, which customers return, which seasons pay. Her hats were custom-made and “one of a kind,” the phrase that sounds like marketing until you remember that millinery is unforgiving: the slightest mismeasurement, the wrong stiffness in the buckram, the poor choice of trim, and the hat loses its authority.

Her clientele included celebrities—names like Ella Fitzgerald and Lena Horne are often cited in accounts of her work—but the more revealing detail is the breadth of her customer base: professional women, church women, teachers, socialites, the kinds of people who understood that a hat can be both armor and celebration.

For many of those customers, the shop was more than retail. It was a gathering place, a neighborhood institution, a Black-owned business that offered dignity as a product and as an experience. The shop’s endurance—decades of operation—meant that a woman could buy a hat for her graduation, return for her wedding, come back for Easter with her children, and later return again for a funeral. A life could be measured in brims.

When the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture acquired Reeves’s collection—hats, furniture, signage—it treated the shop itself as an artifact worthy of preservation. That curatorial decision is significant: it suggests that a Black-owned millinery shop belongs in the national story not only as fashion, but as Black business history, as material culture, as proof of a parallel economy built when the mainstream economy refused entry.

Reeves’s bank loan sits at the center of that proof. It is an unglamorous detail, the kind that never makes it into a glossy fashion spread, and yet it is the detail that explains everything: the rent paid, the supplies ordered, the sign hung, the first customer greeted.

If you want to understand how Black entrepreneurship survives, you could do worse than to begin with $500 and a woman who knew exactly what to do with it.

Mildred Blount: A Milliner Who Refused the Back Door

If Mae Reeves’s story is rooted in a storefront and a community, Mildred Blount’s story moves through institutions that were not designed to welcome her—Hollywood unions, museum galleries, elite salons—and insists, repeatedly, on being taken seriously.

Blount was born in 1907, orphaned young, and entered the fashion world as a teenager in New York, building a life through work and night study. The outline of her early years—day labor, evening education, persistent self-making—resembles the biography of many Black artists whose craft was never supposed to count as “art” in the official record.

But Blount’s career does not read like quiet perseverance; it reads like a series of deliberate confrontations with exclusion. As a milliner, she designed for private clients and for films, and later operated a Beverly Hills hat shop. Her work circulated in the most visible arenas of glamour, yet her presence in those arenas was never guaranteed. The cultural myth of Hollywood elegance often erases the labor behind it; Blount was part of that labor, and also one of the people pushing against how that labor was segregated.

A crucial part of her story involves institutional recognition beyond commerce. In 1939, Blount created a set of miniature hats—meticulous historical studies—that were displayed at the New York World’s Fair, an unusual platform for a Black woman in a field that was already coded as decorative rather than intellectual. The miniature hats were not just charming; they were scholarship in three dimensions, a demonstration that millinery is research as much as it is technique.

Later, Blount’s legacy was formally contextualized by art institutions like the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, which has emphasized how she used her career to break barriers and insist on dignity in spaces that presumed otherwise. That framing matters because it reclassifies millinery: not as “women’s work” to be admired and forgotten, but as design practice—material intelligence, cultural authorship.

Blount, in other words, forces the uncomfortable question: if a hat can reshape how a person is seen, and if it requires mastery of form, texture, proportion, history, and physics—why is it not treated with the same seriousness as sculpture?

The answer, of course, is that seriousness has always been rationed.

Blount’s career stands as evidence that the rationing was never about the work. It was about who was doing it.

Toni Ham and the Festival Economy of Memory

The geography of Black millinery history is not only the familiar corridor of New York–Philadelphia–Chicago–Los Angeles. It is also the regional and local circuits where cultural tradition survives through festivals, churches, family businesses, and the recurring event calendar of community life.

Toni Ham belongs to that map.

Ham worked for decades as a milliner in Tucson, Arizona, hand-crafting blocked hats and demonstrating her process at Tucson Meet Yourself, the folklife festival that acts, for many vendors, as both cultural stage and economic anchor. In reporting about her legacy, the throughline is consistent: she made hats rooted in the Southern Black church tradition—big, ornate, expressive—while living and working in the Southwest, proving that cultural style travels, adapts, and refuses to be geographically contained.

A festival magazine profile described the intergenerational knowledge behind her work—how her mother and grandmother made hats, how store-bought wasn’t always an option, how the craft functioned as both necessity and pride. This is millinery as inheritance: skills transmitted like recipes, with technique braided into memory.

After Ham’s death, the business did not simply disappear. Coverage from a Tucson television station followed her daughter carrying on the legacy at Tucson Meet Yourself, selling the hats and speaking about what they meant—“a lot of color in our culture,” an entrepreneurial spirit passed down. The story is not only sentimental; it is structural. It shows how small Black-owned creative businesses survive: not through venture capital or massive distribution, but through community repetition—annual festivals, returning customers, the durability of a name, the intimacy of a product that people want to touch before they buy.

In 2024, Pima Community College promoted an event that included a silent auction featuring millinery designs from Ham’s collection, linking her work to support for the African American Museum of Southern Arizona. That detail matters because it illustrates how a milliner’s output becomes, over time, cultural capital—objects that can fund institutions, educate audiences, and represent tradition.

Ham’s story is a reminder that millinery is not only about high fashion. It is also about the local economy of beauty—the way art circulates through communities, the way a hat can hold a family together, the way a craft can outlive its maker.

The Contemporary Wave: New Shops, Old Questions

If the historic Black milliners fought for credit, space, and legitimacy, the contemporary generation fights on a terrain that is both easier and harder.

Easier, because the internet allows a Black-owned millinery brand to build an audience without waiting for gatekeepers. Harder, because digital commerce collapses attention spans, forces constant marketing, and intensifies price competition against mass-produced goods.

And yet the best contemporary Black-owned milliners still operate with the old values: fit, craft, storytelling, relationship. You can see it in how they describe their work—less like product, more like identity.

Frances Grey Millinery: Inheritance as Design Language

Frances Grey, the New York-based millinery brand designed by Debbie Lorenzo, reads at first glance like an argument for restraint: clean lines, strong silhouettes, an emphasis on form. The brand frames itself as handcrafted, custom, and rooted in heritage—explicitly inspired by Lorenzo’s great-grandmother, Frances Grey, a Jamaican seamstress whose legacy becomes the brand’s namesake.

In the contemporary millinery landscape, where “statement” often means maximalism, Frances Grey’s statement is precision. The hats are designed to be worn repeatedly, not once; to sit in a wardrobe like a signature, not a novelty. The brand’s own language emphasizes custom sizing and personal style—an echo of traditional millinery practice, updated for a clientele that may discover the brand online but still wants the intimacy of something made for their head.

Third-party profiles have highlighted Lorenzo’s background and the brand’s positioning as woman- and Black-owned, situating it within the broader movement of consumers seeking out businesses that carry cultural meaning alongside aesthetic value. The most interesting aspect of Frances Grey, though, is how it uses lineage as design logic: the brand does not treat ancestry as marketing copy, but as a constraint that shapes decisions—what kinds of hats belong under this name, what kinds do not.

In that sense, Frances Grey is part of an older millinery tradition: hats as family grammar. You learn what a brim can say by watching the women who wore them before you.

Harlem’s Heaven Hats: Uptown Craft, Global Recognition

In Harlem, Evetta Petty has spent decades doing what the best milliners do: serving a local community while quietly producing work that travels far beyond it.

Harlem’s Heaven Hat Shop, Petty’s studio and retail space, is rooted in the neighborhood—its address history, its customer base, its function as a place where people come to be fitted not just for events but for moments. A 2014 profile described the shop as a destination and noted Petty’s inventory depth and signature boldness.

But the modern Harlem story is also international. The Headwear Association named Petty its 2025 Retailer of the Year, citing her decades of designing in Harlem, her FIT background, and the way her hats show up at global style events like Royal Ascot and the Kentucky Derby.

Petty’s own biography, as presented by Harlem’s Heaven, claims a milestone that speaks to both fashion and racial firsts: her inclusion in the Royal Ascot Millinery Collective, described as the first Black milliner invited into that group. Even allowing for the complexity of “first” claims—fashion history is messy, and documentation is uneven—the underlying fact stands: Petty’s work has been recognized in one of the most tradition-bound millinery arenas in the world.

In 2025, Vogue published a reported piece on Easter Sunday style at Abyssinian Baptist Church and included a congregant who noted that her hat came from Harlem’s Heaven—an incidental detail in a fashion story, but one that reveals how a neighborhood milliner becomes part of a community’s ritual life. In that moment, Harlem’s Heaven isn’t “a brand.” It’s the place you go when you want to look right for church, for family photos, for yourself.

That is the secret power of Black millinery: it is local, until it is suddenly global, and even then it remains local.

House of Brims: The Brim as Identity Project

House of Brims, founded by Avana McKoy, approaches hats with a language that is explicitly generational. On the brand’s “Our Story” page, McKoy attributes her love of hats to her grandmothers and dedicates the brand to their legacy.

That framing matters. Many contemporary brands sell hats as “style.” House of Brims sells hats as continuity—an attempt to keep the brim from becoming a novelty in a culture that constantly moves on. In at least one mainstream-style roundup of Black-owned western brands, House of Brims was positioned as modernizing classic designs while keeping the timeless appeal intact.

The brand name itself—House of Brims—sounds like a thesis: the brim is the point. It’s a declaration that the hat is not an afterthought, but the structure around which the look is built.

Historically, Black milliners understood this instinctively. A brim changes posture. It changes how you enter a room. It changes how you are photographed. To build a house around brims is, in a subtle way, to build a house around agency.

TomGFashion: Streetwear Energy, Fedora Discipline

TomGFashion sits at a different intersection: more digital-first, more accessory-driven, closer to the cadence of streetwear and everyday styling than to the formal church calendar.

The brand’s storefront language is direct: “All the hats that you need,” “unisex,” ready-to-ship fedoras, quick fulfillment. The product assortment emphasizes variety—colors, bands, wide brims—suggesting a business built for volume and online browsing rather than exclusively for bespoke appointments.

In millinery terms, this is an important contemporary shift. Historically, many Black milliners built their businesses through custom work and in-person fittings. Digital-first brands like TomGFashion translate hat culture into the logic of e-commerce: standardized sizing ranges, accessory add-ons, rapid shipping, frequent drops.

That translation comes with tradeoffs—less intimate fitting, more reliance on the customer’s self-measurement—but it also broadens access. It allows a customer who may not live near a millinery shop to still participate in hat culture, to put a fedora into rotation the way they might put sneakers into rotation.

TomGFashion’s significance, then, is not only aesthetic. It’s infrastructural. It reflects how Black-owned hat businesses adapt to an era where the shop might be a URL and the customer might be anywhere.

What Milliners Know That Fashion Often Forgets

Spend time around milliners and you learn quickly that they are part engineer, part psychologist.

They know the mechanics: how felt behaves in humidity; how straw responds to travel; how a crown must be balanced so the brim doesn’t dip; how a hat must accommodate hair—natural, braided, loc’d, covered, uncovered—without treating Black hair as an inconvenience. They also know the human variables: how someone holds grief in their shoulders, how someone wears confidence differently at 25 than at 65, how a person can want to be seen and protected at the same time.

In the Black millinery tradition, those two kinds of knowledge—material and emotional—have always been linked. Hats are worn at the moments when life is loud: celebration, mourning, witnessing. The milliner becomes, almost inevitably, a quiet archivist of community transitions.

This is why the business side matters so much. If the shop closes, it isn’t merely retail loss; it’s cultural loss. A neighborhood without a milliner becomes more dependent on generic fashion, less able to produce its own visual language.

Mae Reeves understood this when she turned a bank loan into a landmark. Mildred Blount understood it when she insisted her work belonged in serious institutions. Toni Ham understood it when she returned, year after year, to the festival circuit—selling, demonstrating, teaching without necessarily calling it teaching.

And the contemporary milliners understand it when they build brands that are not just “cute hats,” but cultural projects: Frances Grey turning ancestry into design discipline; Harlem’s Heaven tying a Harlem storefront to Royal Ascot recognition; House of Brims centering grandmothers as brand origin; TomGFashion pulling fedoras into a fast-moving digital marketplace.

Different strategies, same underlying principle: the hat is a way to claim space.

The Brim, Reconsidered

Fashion moves in cycles, but tradition moves differently. Tradition is not “back.” It is continuous.

When a Black woman chooses a hat for Easter, she is not participating in a trend. She is participating in lineage. When a Black entrepreneur opens a hat shop, they are not merely selling accessories. They are restoring infrastructure—making it possible for people to look like themselves in public, on their own terms.

In an era when so much of style is flattened by algorithms, millinery remains stubbornly physical. You can’t fully digitize the moment a hat settles onto a head and the wearer’s posture changes. You can’t mass-produce the quiet pride of a customer who sees themselves in a mirror and thinks: yes, that’s me.

The historic and contemporary Black-owned milliners—Reeves, Blount, Ham, and the living shops carrying the work forward—show that the brim has always been more than a brim.

It’s a boundary line between how the world looks at you and how you insist on being seen.

And, often enough, it’s a business plan—made of felt, wire, ribbon, and the kind of nerve that turns a small loan, or a small shop, or a small festival table into a legacy.