By KOLUMN Magazine

Before the door opened, the line formed.

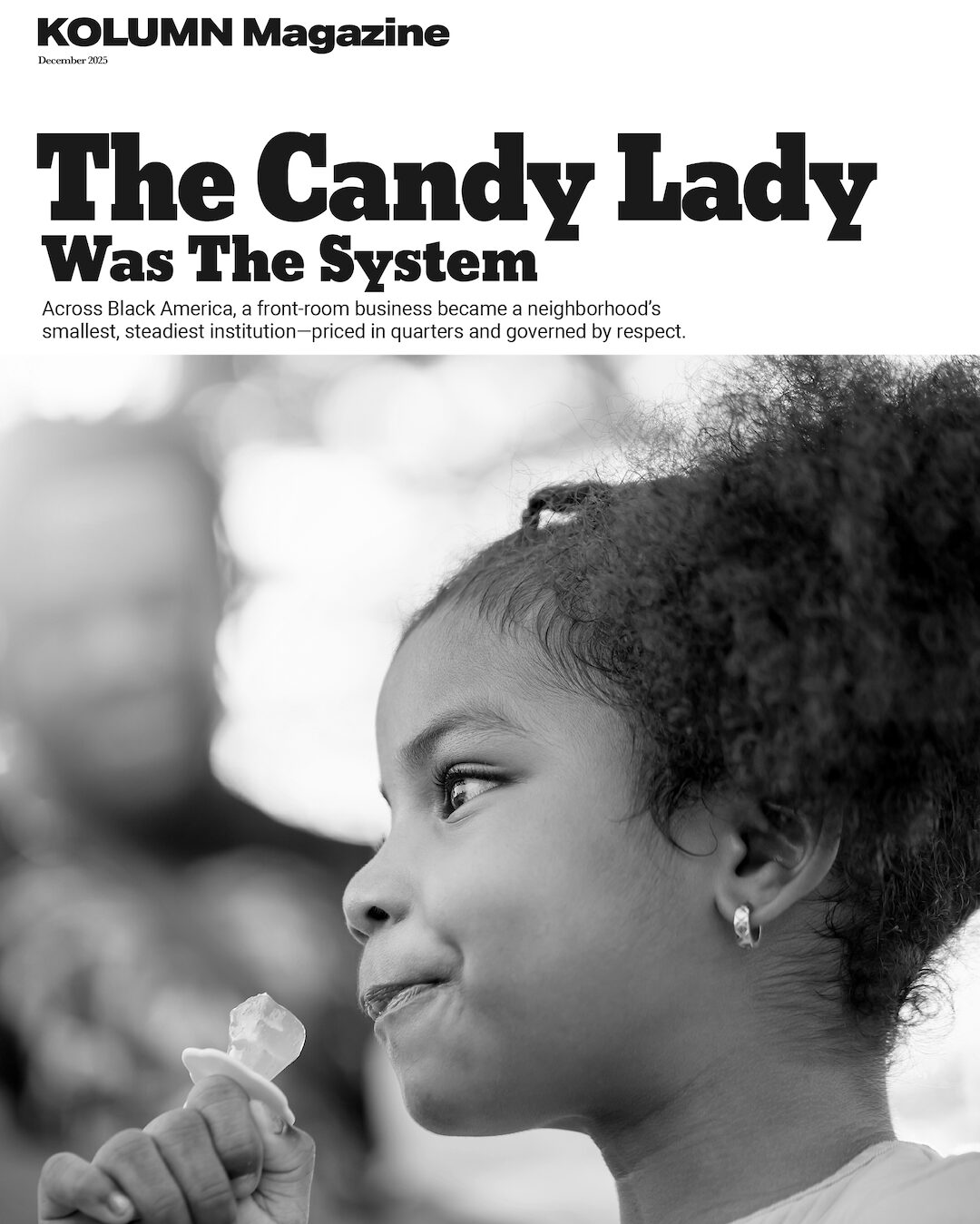

Children arrived in small clusters—two cousins, a neighbor’s little brother, someone’s baby sister trailing behind—coins warmed by pockets and palms. Orders were rehearsed the way grown people rehearse directions: two pickles, a blue frozen cup, hot chips if she got change. Someone always volunteered to knock. Someone always hesitated, because mood mattered, and the Candy Lady’s house was not a store in the way America defines a store. It was a home performing a public function. That distinction governed your voice, your posture, your patience.

There was rarely a sign. Sometimes there was a cooler that appeared like a stage prop at the edge of a porch. Sometimes there was a mailbox that carried the secret in plain sight—one word, one hint, just enough for kids who already knew. Most often, there was only habit: the turn down the right block, the pause on the first step, the understanding that the transaction you were about to make had rules the city could not post for you.

For many Black Americans, “the Candy Lady” is a memory so universal it can feel folkloric—one of those childhood references that prompts a smile before you’ve even decided you’re smiling. Yet if you treat the Candy Lady as nostalgia, you miss what she reveals: a neighborhood institution built at the scale of the living room.

She sold candy, yes. She sold chips and pickles and juice and sometimes baked goods bought in bulk and resold as individual portions. She sold frozen cups—Kool-Aid or fruit drink poured into plastic sleeves and frozen solid—called different names in different places, but recognized everywhere as the price of surviving summer. And she sold something else, less sentimental and more consequential: predictability.

The Candy Lady was a micro-economy calibrated to scarcity and a safety system that didn’t call itself one. In neighborhoods shaped by segregation, underinvestment, food deserts, and over-policing, the Candy Lady’s enterprise often filled gaps the formal economy left behind. She made childhood more navigable: one less hungry hour, one less unsupervised stretch, one more adult who knew your name and knew how to enforce a rule without calling the state.

To call her a “small business” is accurate and also insufficient. The Candy Lady was commerce braided into care—mutual aid with a price tag, childcare funded by snacks, block governance conducted in quarters.

And like most infrastructure in Black America, she was simultaneously ordinary and heroic: so common she was rarely documented, and so vital you could feel her absence when she disappeared.

The House Store: Domestic Space as Public Good

The Candy Lady’s storefront was almost always domestic. A living room repurposed. A kitchen counter cleared. A freezer placed strategically near the door. Shelves that climbed walls that once held family photos. The arrangement differed by household, but the logic was consistent: the home became a neighborhood node.

This matters because the Candy Lady’s authority did not operate like a cashier’s authority. It operated like an Auntie’s. She did not need signage to regulate behavior. Her rules were transmitted through reputation and reinforced through consequence. You didn’t fight at her door. You didn’t disrespect her house. You didn’t touch what you couldn’t pay for. You said thank you. If you broke the code, your punishment wasn’t a fine; it was banishment—being told not to come back, which for a child could feel like exile from the block’s center.

A public-radio story about Chicago’s West Side summertime vending economy—candy sellers, pop vendors, Icee sellers, cake ladies—captures the breadth of this ecosystem and, crucially, the recognition that it constituted “a whole economy,” a neighborhood infrastructure that many people only name once they’re grown.

The Candy Lady sits at the most intimate end of that economy: the smallest retail unit and, often, the most stable. Her business relied on what formal systems tend to undervalue: trust, proximity, and the ability to manage a crowd with nothing but voice and standing.

If you want to understand why she mattered, you don’t start with the candy. You start with the line.

The line tells you who depends on her. The line tells you who is hungry and who is bored and who needs a safe place to stand for ten minutes. The line tells you which children know how to count change and which children are learning. The line also tells you that the neighborhood has created a solution that requires no grant application, no ribbon cutting, and no outside approval.

The Candy Lady did not emerge from whimsy. She emerged from absence.

The House that Held the Block

In Memphis, the Candy Lady is remembered by address.

Ask anyone raised in Orange Mound or South Memphis and you will not get an abstract description. You will get directions: three doors down; across from the church; by the lot where kids played until the streetlights came on. The Candy Lady’s presence is woven into the neighborhood’s internal map in the same way a corner store or a park might be—except the Candy Lady’s place is not commercial property. It is personal property deployed for the public.

One of the clearest written portraits of this tradition comes from a profile of Deidra Tuggle, known as the Candy Lady of Orange Mound, described as a “generational businesswoman” whose home provides “a safe spot for kids looking for an afterschool snack and a smile.” The phrasing is warm, but the underlying point is sharper: safety is a product, too.

In Orange Mound, a historically Black neighborhood with a deep civic identity, the Candy Lady’s house often functioned like an after-school anchor. Kids who didn’t have rides and didn’t have time and didn’t have adults waiting at home could stop there. A frozen cup bought for a quarter did more than cool you down; it bought you a moment inside an adult’s orbit.

The mechanics of the business are deceptively simple. A cooler. A freezer. Bulk candy bought at a wholesale store. Chips stacked in a basket. But the mechanics of the role are complicated. The Candy Lady becomes a gatekeeper: not just of snacks, but of behavior. She enforces quiet rules that shape public life. You don’t bring trouble to her door. You don’t use her steps as a stage for conflict. You don’t make her house the site of block drama.

The children learn this early. They learn it the first time she looks past the candy and into their eyes and says, Not today. They learn it when she calls someone “baby” in a tone that means the opposite of indulgence. They learn it when she hands over the change with a lecture folded inside: Say thank you. Don’t run. Watch that little one.

Because the Candy Lady runs a business in her home, her authority includes vulnerability. Her front door is not a counter protected by Plexiglas; it is a threshold into her life. She cannot call security. She is security.

That vulnerability is part of why the neighborhood responds when she is harmed.

A local news report about Orange Mound rallying to help a Candy Lady rebuild after a house fire explicitly frames her home as a “safe haven” for neighborhood kids—and frames the fire as a communal loss, not only a personal one. This is what it means for a domestic enterprise to be infrastructure: when it goes offline, the neighborhood’s daily operating system changes.

Memphis even memorializes the archetype in popular crime television. A description of an episode of The First 48 set in Memphis centers on the killing of a “beloved neighborhood Candy Lady,” shot through her closed front door—an image that is horrifying precisely because it violates the understood sanctity of her role. (AETV)

These references—profile, news clip, cultural artifact—trace a truth that residents already know. In Memphis, the Candy Lady does not merely sell candy. She stabilizes the afternoon.

And sometimes, that stabilization is the difference between a child getting home safely and not.

What the Memphis Candy Lady taught

Adults who grew up with a Candy Lady in Memphis tend to remember her as a combination of warmth and enforcement. The candy is what you can name. The enforcement is what you carry.

A former child-customer might describe the approach as a negotiation: you step onto the porch, you scan the face, you decide whether today is a day for requests. If you are short on change, you do not plead; you ask carefully, because you’re not just buying snacks—you’re asking a neighbor to extend trust.

This is the part that rarely makes it into “remember when” conversations: the Candy Lady teaches financial and social literacy simultaneously. Count your money. Speak respectfully. Don’t embarrass yourself. Don’t embarrass your people.

In a neighborhood where many kids are asked to grow up quickly, the Candy Lady is one of the few places where childhood is permitted to exist under supervision.

From House to Network

As Black families moved and as neighborhoods adapted, the Candy Lady role multiplied. In some cities she remained rooted to one house. In others she became part of a broader informal vending system: candy, pop, Icees, cake slices—an economy operating in plain sight.

What changes from city to city is the form. What remains is the function: low-cost access, local knowledge, and a code of conduct enforced without bureaucracy.

In Chicago, the Candy Lady belongs to a network.

Chicago: The Quarter Economy and Early Ownership

Chicago’s West Side summertime economy, documented by WBEZ, reads like an inventory of a childhood world: “the candy lady, the pop lady, the Icee lady, the cake lady.” The quote lands with the clarity of hindsight when the speaker—now thinking as an “entrepreneurship director” and “economic development” advocate—realizes: “this is a whole economy.”

Chicago is a city that understands formal commerce in grand terms: towers, trading, corporate headquarters. The Candy Lady is Chicago commerce in miniature: cash in hand, inventory in a freezer, neighborhood demand measured by foot traffic and heat.

On the West Side, the Candy Lady often serves as an anchor of reliability. Her house is fixed. Her hours are informal but consistent. Her rules are understood. Other vendors may be seasonal or mobile; the Candy Lady is the steady address.

For child customers, that steadiness becomes a training ground.

They learn pricing early because they have to. A child’s budget is not a theoretical number; it is whatever coins can be found in a couch, earned from chores, or collected from a parent who is stretching money across bills. The Candy Lady teaches the mathematics of limitation: what you can afford, what you can’t, what you can split with a sibling, what you can buy now and what you must wait for.

They learn inventory logic, too. A flavor runs out. A popular chip disappears. Certain days are better than others. Business becomes visible as a living thing, not an abstract concept.

In Chicago, this can matter profoundly because economic opportunity has often been unequally distributed across neighborhoods. When formal institutions fail to provide stable employment and safe recreation and neighborhood amenities, informal economies fill part of the gap. The Candy Lady’s enterprise demonstrates ownership at a scale a child can touch.

Yet the Candy Lady is not only a business lesson. She is block governance.

Her doorway functions like a border checkpoint. You do not bring chaos into her space. You do not use her yard as a stage for fighting. You do not curse loud enough that she has to hear it. Her authority is not derived from the state. It is derived from the community’s agreement that she is to be respected.

WBEZ’s reporting, while framed around summertime treats, implies something bigger: this economy is also a social system. Vendors know families. Families know vendors. Trust circulates alongside money.

What The Chicago Candy Lady Enforced

If you ask former Chicago child-customers what they remember most vividly, many will tell you about the moments you got corrected.

Not by your mother, not by your teacher, but by a woman who was not obligated to correct you at all—and did it anyway.

That correction might have been small: “Don’t cut the line”; “Don’t slam my screen door.” It might have been larger: “Don’t show up here with stolen money”; “Don’t bring trouble to my house.”

The Candy Lady teaches boundaries that are both moral and operational. She is protecting her business, yes. She is also protecting the neighborhood’s social order.

The quarter economy looks like play. But it is also how children learn accountability in a world that will punish them harshly for the smallest mistakes.

In cities where violence and policy pressure shape neighborhood life, the Candy Lady’s role takes on another dimension: she becomes a waypoint.

Her house is not just a store; it is a known coordinate on a child’s map. A stop to break a bill. A place to wait for a friend. A house where adults are present.

Philadelphia shows what happens when the Candy Lady moves. Washington shows what happens when she stays put.

Washington, D.C.: Refuge In Plain Sight

Washington, D.C. is a city of official addresses. Agencies. Think tanks. Legislators. Titles. But the Candy Lady belongs to the city’s unofficial infrastructure—the set of places and people who make daily life possible beyond the government’s view.

What distinguishes the Candy Lady in D.C. is the way she appears in narrative as an assumed fact. People mention her in passing because she is part of how neighborhoods work: a known destination, a reliable stop, a house that functions as a community node.

That reliability matters in neighborhoods shaped by both neglect and scrutiny. D.C.’s Black communities have navigated gentrification, uneven services, policing practices, and a constant churn of political rhetoric about safety and development. In that environment, the Candy Lady’s home offers care without paperwork. Safety without institutional surveillance. A place children can go that is neither school nor their own home but still contains an adult’s watchfulness.

In many blocks, the Candy Lady’s work is not limited to selling snacks. It often extends into small acts of community maintenance: making sure kids aren’t fighting, sending them home when it’s getting too late, calling a parent if a child is acting out. Sometimes it extends into feeding adults, too—quiet generosity that blurs the line between commerce and mutual aid.

That blurring is one of the Candy Lady tradition’s most important truths: the transaction is real, but the relationship is larger than the transaction.

And because the relationship is larger, harm to the Candy Lady registers as harm to a public institution. The neighborhood doesn’t experience it as “a vendor.” The neighborhood experiences it as “one of ours.”

Customer narratives: What the D.C. Candy Lady Provided

A D.C. child-customer might remember the Candy Lady as a place you could stop when you didn’t want to go straight home—when home was loud, or crowded, or uncertain. Ten minutes at her door could be a buffer. A way to transition. A way to be seen.

This matters because Black childhood is often surveilled and criminalized in ways that make public space dangerous. The Candy Lady’s doorstep—private property with a public function—can feel like one of the few places where a child is allowed to exist without being read as a threat.

In that sense, the Candy Lady is not simply convenience. She is shelter.

If Memphis and D.C. emphasize the Candy Lady as a rooted home-based institution, Philadelphia offers another form: the Candy Lady as mobile culture-bearer.

She takes the same core function—accessible snacks, familiar presence—and moves it through the city like a living landmark.

Philadelphia: The Candy Lady as Folk Icon In Motion

In Philadelphia, the Candy Lady tradition includes a figure who has become visible enough to be profiled as a local icon: “the Philly Candy Lady,” also described in scholarly work as the “Singing Candy Lady,” Lynette D. Morrison.

A 2025 academic article frames Morrison as “a beloved folk icon in Philadelphia, especially among Black working-class residents,” describing her moving through the city with a yellow box of candy, singing, joking, and encouraging people to buy. In other words, the Candy Lady role becomes performance—yet the performance is not separate from function. It is part of the function.

A KYW Newsradio/Audacy profile describes where you might find her—“on 52nd Street,” near a Walmart on Roosevelt Boulevard, on South Street—carrying a peanut M&M’s box filled with assorted candy, balancing it on her head while singing, dancing, and joking with people she meets. The line that matters most is the one that reveals purpose: “My goal is just to make people smile… It’s to make people laugh.”

On its surface, this sounds lighter than the house-store model. But the framing insists on depth: her presence “inspires a sense of place for those who reside in dispossession.” That phrase—sense of place—is not academic decoration. It is a description of what happens when a city’s built environment and political environment have made belonging unstable. A familiar figure becomes a moving stitch, binding blocks together through recognition.

Philadelphia’s Candy Lady is not hidden behind a screen door. She is visible, audible, documented. Social media circulates her image. Local media names her. She becomes “public” in a way that many Candy Ladies do not.

Yet the underlying logic remains unchanged: low-cost exchange, familiarity, emotional labor. Candy is the medium. Connection is the product.

Customer narratives: what Philadelphia’s Candy Lady restores

A passerby who buys candy from a street vendor isn’t just buying sugar. They’re buying an interaction. They’re being addressed as a person.

This is a form of neighborhood life that policy rarely measures: the everyday exchanges that reduce alienation.

In a city where displacement has reshaped Black neighborhoods repeatedly, the Singing Candy Lady’s mobility asserts continuity. She shows up. She is heard. She is recognized. And in that recognition, people locate themselves again.

The Tradeoffs No One Romanticizes

A serious accounting of the Candy Lady cannot stop at celebration. The tradition exists inside contradictions.

Health and food environments. Candy, chips, sugary drinks—these products sit uneasily beside public-health concerns. But the Candy Lady did not engineer the food environment. She operates within it. When neighborhoods have fewer affordable options, the “small” sellers become the accessible sellers. The Candy Lady’s inventory reflects what people will buy with limited money and limited time.

Informality and vulnerability. Many Candy Lady businesses are informal by design. That informality can be protective—less bureaucracy, fewer barriers, less visibility to predatory attention. But it also produces precarity. A home-based business can disappear overnight due to illness, fire, eviction, violence. The Orange Mound house-fire story underscores this fragility: when her home went offline, a communal support point went offline with it.

Gendered labor. Candy Ladies are often women—sometimes grandmothers, aunties, women raising children and grandchildren, women stitching income together. The neighborhood’s dependence can become a burden. The expectation that she will always be there is itself a pressure.

Safety. The Candy Lady’s presence can deter chaos, but it cannot eliminate the structural conditions that produce violence. And because her house is a known destination, it can also be vulnerable. The Memphis First 48 description—“beloved neighborhood Candy Lady” shot through her closed front door—illustrates the terrifying breach of what should be safe.

The Candy Lady isn’t an answer to systemic failure. She is proof of how communities adapt inside it.

A national institution with regional accents

What’s striking about Candy Lady culture is not only how widespread it is, but how locally it is adapted.

In Memphis, the Candy Lady is often rooted—house-as-haven, after-school anchor, governed by neighborhood reputation.

In Chicago, she sits inside a broader informal vending system that amounts to “a whole economy” and an apprenticeship in ownership.

In Washington, D.C., she operates as a waypoint—an unofficial address in a child’s daily navigation and a pocket of care beyond institutional scrutiny.

In Philadelphia, she may be mobile—street performance as place-making, candy as a vehicle for public joy and recognition.

Even the names change: candy lady, freeze-cup lady, pop lady, cake lady. The title is flexible because the function is what persists.

What the Candy Lady Reveals About Black Governance

The Candy Lady is not a cute footnote to Black childhood. She is evidence of governance.

Governance is not only legislation. It is also the management of daily life: who watches children when adults are working; who provides food when paychecks are short; who enforces norms when the police are either absent or dangerous; who offers a safe point on a block where safety is not guaranteed.

The Candy Lady does all of this with no budget line and no official mandate. She does it because the neighborhood needs it and because she has decided—through whatever mixture of necessity, opportunity, and calling—that she will be the one to do it.

In Chicago, the WBEZ story’s recognition—“this is a whole economy”—is more than an observation about snacks. It’s a recognition about capacity: the neighborhood is not waiting to be saved; it is building itself in miniature.

In Orange Mound, the Candy Lady’s home is explicitly described as a safe spot—an after-school refuge—and when that refuge is threatened, the community responds as though infrastructure has been damaged.

In Philadelphia, scholarship treats the Singing Candy Lady as a folk icon whose everyday performance creates “sense of place” amid dispossession—an argument that reframes candy vending as cultural labor with political stakes.

Taken together, these accounts insist on the same point: the Candy Lady is not simply a person who sells candy. She is a neighborhood function made flesh.

Ending Where We Began: The Line at the Door

Return to the line—because the line is where the story is most honest.

A child stands there with change in hand, rehearsing an order. Behind the order is a need: for sugar, for salt, for something cold, for a moment off the street, for an adult to witness them without suspicion.

The Candy Lady opens the door. She looks them over—eyes first, then money. She counts the coins quickly. She hands back the snack with change and, sometimes, a small instruction wrapped inside: Don’t run. Watch your sister. Say thank you. Get home before it’s dark.

What she sells is small. What she provides is large.

In a country that often refuses to fund Black neighborhoods the way it funds others, the Candy Lady is one of the clearest demonstrations of what Black communities have always done: build systems anyway.

No sign on the door. No absence of power.

Just a screen door opening, a freezer humming, and a neighborhood quietly held together—one quarter at a time.