The Cold She Refused to Accept

In 1919, Alice H. Parker patented a new way to heat a home. History never bothered to warm to her.

By KOLUMN Magazine

Morristown, New Jersey, in winter is the kind of cold that has a personality. It comes in through the seams—at the sill, beneath the door, around the window sash that won’t quite settle into its frame. It lives in the stairwell. It clings to the back rooms. In older houses, you can feel it “zone” the place into winners and losers: the parlor where the fire is, the kitchen where work keeps you warm, the bedrooms where breath turns thin.

For a young woman in the early 20th century, living inside that cold was not merely discomfort; it was a daily tutorial in systems—airflow, heat loss, the tyranny of distance between a flame and a room you still need to inhabit. The hearth might glow, but it did not travel. And travel, for the person tasked with making a household functional, was the real tax: carrying wood, hauling coal, feeding a fire, watching it, banking it, waking to revive it.

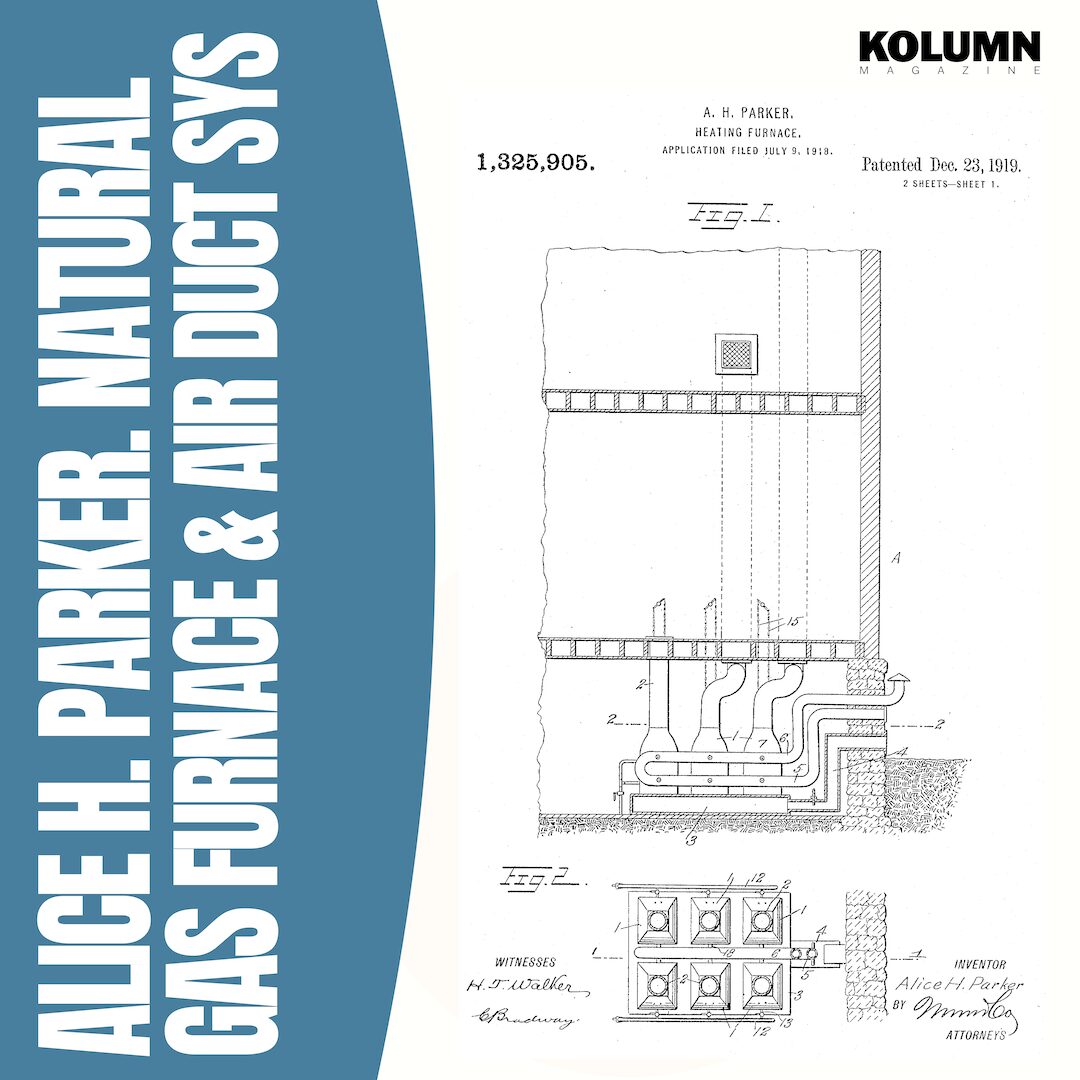

Alice H. Parker left behind only a sliver of herself in public documents. What survives most clearly is not a photograph or an interview, but a technical claim filed with the United States government: a patent for a “new and improved Heating-Furnace”—a system that imagined warmth not as a single blaze in one room, but as a distributed service: controllable, ducted, and powered by gas.

Her patent is dated Dec. 23, 1919. It is a winter date, and that feels fitting—because the story of central heating is, in the end, a story about what happens when a private hardship becomes an engineering problem someone decides to solve.

Parker’s legacy has often been summarized too neatly: “the Black woman who invented the gas furnace.” The truth is both more modest and, in a way, more impressive. She did not conjure heat from nothing; she rearranged the logic of how heat could move through a building and how occupants could govern it—anticipating ideas that later become standard in HVAC design: multiple burners, controlled distribution, and zoned regulation.

But before any of that—the claims, the diagrams, the language of “comparatively simple, reliable, and efficient”—there is the problem she lived with: cold that refused to behave.

The Early Life We Can See—And the Early Life We Can’t

Writing about Parker means writing around absence. The sources agree on a few anchor points: that she was associated with Morristown, New Jersey; that she attended Howard University Academy (a preparatory school associated with Howard) and received recognition for graduating with honors; that she was a Black woman working in an era that did not preserve Black women’s biographies with any seriousness or consistency.

Even those seemingly straightforward facts arrive with caveats. A careful 2022 reporting project noted how frequently Parker’s identity has been muddled, including the circulation of photographs wrongly labeled as her. The result is a public figure made out of fragments: a name, a location, a patent, and a digital afterlife that sometimes values inspiration over verification.

Still, the contours of her early life can be sketched responsibly—not with invented color, but with contextual realism.

To be a young Black woman in New Jersey at the turn of the century was to live in a country that had ended slavery but was busy perfecting segregation by other means—through labor markets, housing, schooling, and law. To seek education in Washington, D.C., at an institution linked to Howard, was not simply personal ambition; it was a logistical and cultural feat. The Lemelson-MIT archive notes the basic outline—born in 1895, later attending classes in Washington—and emphasizes how little documentation exists precisely because of who she was in that time.

Howard University’s own alumni storytelling frames Parker as a 1910 graduate of its Academy program, situating her in the world of Black educational striving: classrooms built as counter-architecture to a society that preferred Black genius remain private, informal, and deniable.

What might she have studied? No transcript survives in commonly cited repositories, and responsible accounts avoid pretending otherwise. But her patent drawings—precise enough to communicate a multi-burner, ducted design—signal fluency with mechanical reasoning, whether learned in school, at work, through observation, or through the practical intelligence of necessity.

This is the biographical tension at the center of Parker’s story: she is both legible and unknowable. The government could record her as an inventor. The broader culture could fail to record her as a person.

The Problem She Tried to Solve: Heat as Labor

Parker’s patent arrives at the end of a long era when home heat was inseparable from household labor.

Before widespread central heating, comfort was uneven. Many families depended on fireplaces, stoves, or localized heaters. They also depended on fuel that had to be purchased, transported, stored, and fed into flame—tasks that cost time and created mess and risk. The Lemelson-MIT summary underscores the everyday burden: wood to chop or coal to stockpile, and the danger of leaving a fire burning overnight.

Parker’s conceptual leap was not simply “use gas.” Gas existed; it was used for lighting and some appliances. What she proposed was to treat heat like a system, where fuel, combustion, exchange, and distribution were integrated—and, crucially, where different spaces could be heated differently.

In the patent itself, her language is careful and pragmatic. She describes a heating furnace designed for efficiency and flexibility—an apparatus that uses gas as fuel and distributes warmed air through ductwork. The diagrams show multiple burners feeding into a common exchange and channels that imply controlled delivery.

Today, “zoning” is a feature marketed in glossy brochures: tailored comfort, individualized control, modern convenience. In 1919, it was a rethinking of domestic architecture. If you could decide where heat went, you could decide which rooms were livable. You could reduce waste. You could make the upstairs less punishing. You could make sleep less interrupted. And you could detach warmth from the constant vigilance of keeping a flame alive.

This is why Parker’s invention, even if never manufactured as she drew it, still matters: it articulated a future in which comfort could be engineered and governed, not merely endured.

Inside the Patent: Parker’s Approach to Invention

Patents can read like a hybrid of confession and contract. The inventor must reveal enough to prove originality, while claiming enough to protect it. Parker’s patent belongs to that tradition. It is not a manifesto. It is a proposal.

1) Start from a lived inefficiency

Multiple reputable summaries agree on the origin story: New Jersey winters, fireplaces that did not heat an entire home, and a determination to imagine something safer and more effective.

Whether Parker wrote about that discomfort in a diary we will never read is unknown. But the problem appears clearly in the solution: centralized heat, distributed air, reduced reliance on constant solid-fuel tending.

2) Treat fuel as an input, not the identity

She chose gas not as a novelty but as an enabling constraint. Gas could be delivered through lines, controlled through valves, and burned without the same daily hauling routine required by coal and wood. Howard’s alumni feature notes that coal and wood were common fuel sources and frames gas as safer and more accessible for her design logic.

3) Break a single furnace into controllable units

Lemelson-MIT emphasizes what made her design distinct: multiple, individually controlled burner units rather than a single, monolithic source.

This is the signature of her approach: solve comfort not with brute force, but with modulation.

4) Think in flows: intake, exchange, distribution

The patent’s engineering logic is a choreography: draw in cooler air, heat it via exchange, send it through ducts. That basic model—intake, heat exchange, distribution—is a skeleton recognizable in modern HVAC systems, even where materials and controls have evolved.

5) Accept that invention is often “too early”

A recurring point in reputable summaries is that Parker’s exact design was not implemented at scale in her time, in part due to limitations in regulating heat flow safely and precisely. The Lemelson-MIT write-up notes these concerns directly while still emphasizing her influence as a precursor to thermostats and zoning.

This is not failure; it is a common pattern in technological history: someone designs a concept that requires a supporting ecosystem—controls, sensors, manufacturing capabilities—that does not yet exist.

A Missing Archive, A Noisy Internet

If Parker had lived later—if she had patented in the era of trade magazines, radio interviews, local-business profiles—her biography might be thick with quotations, acquaintances, and context. Instead, she is an example of how Black women’s innovation can be both celebrated and mishandled: her name invoked as proof of progress while the specifics of her life are treated as optional.

The most careful reporting on her story has, paradoxically, focused on what we cannot verify—especially images and biographical claims that circulate without sourcing. The 2022 investigation referenced in multiple summaries underscores that even photographs often presented as Parker are misattributed.

This matters because invention stories are routinely flattened into moral fables. Parker’s real story—patent-backed, diagrammed, located in Morristown—does not require embellishment. But it does require restraint.

The House as a Financial Instrument: Why “Bank Customers” Belong in This Story

To understand why Parker’s idea mattered—and why it took time for the broader housing stock to resemble what she imagined—you have to talk about money. Not only the money to invent, but the money to adopt.

A furnace is not merely a machine; it is a home improvement. It is ductwork threaded through walls. It is labor and retrofitting. It is a capital expense that many households cannot pay out of pocket, particularly in the years when wages are tight and credit is unevenly distributed.

In the United States, access to home improvement capital has long been entangled with banking practices—and with race.

Modern explanations of redlining make the core point plainly: banks excluded Black and Brown Americans from loans to buy homes and to make improvements, shaping neighborhood conditions and wealth accumulation across generations.

And while Parker’s patent predates the institutionalization of HOLC maps and FHA underwriting standards, the larger pattern—credit steering, risk narratives, the unequal valuation of Black neighborhoods—eventually determined who could modernize their homes and who was left with older, less efficient systems. The National Archives’ overview of the Great Migration provides the broader demographic and historical context for Black movement and urban housing pressures in the decades that followed.

This is where the “bank customers” lens becomes essential: the people who live inside an invention’s promise are often the people least able to purchase it, finance it, or retrofit their way into it.

The Hidden Customer: The Borrower Who Wants Warmth

Consider what it means, in practical terms, to convert a home from a stove-and-fireplace heating regime to a more centralized, controllable system. It is not a single purchase. It is a project. That project usually requires either savings or credit.

Contemporary housing research shows that disparities in home quality and improvement financing persist, reflecting a long history of discriminatory access to capital. The Urban Institute notes, for example, that Black homeowners experience higher rates of inadequate housing—an outcome tied in part to historical exclusion from certain neighborhoods and to constrained improvement resources.

That is not a footnote to Parker’s story; it is part of the afterlife of every domestic technology. Invention creates possibility. Finance distributes it.

The Bank As Gatekeeper of Comfort

A Harvard Kennedy School explainer captures redlining’s mechanism in a single sentence: banks excluded Black and Brown Americans from loans to buy homes and make improvements.

If you cannot access favorable credit, you delay repairs. You make do. You rely on older systems. You accept drafts, space heaters, localized warmth. Over time, that affects energy costs, safety, health, and property value—turning the question “How do you heat your home?” into a quiet measure of financial inclusion.

Even in the present, regulators still bring cases against lenders for redlining majority-Black neighborhoods—evidence that the banking dimension of home access and home improvement is not simply historical.

So when we tell Parker’s story, we should be honest: her invention helped sketch a more modern heating future, but the ability to live in that future has never been equally financed.

The Technology That Followed: Thermostats, Zoning, and the Modern HVAC Imagination

One reason Parker’s patent remains culturally potent is that it points toward systems people now consider ordinary: thermostatic control, ducted air, zoned comfort. Lemelson-MIT explicitly frames her design as a precursor to modern zone systems and thermostats, even while acknowledging that her specific configuration was not produced as-is.

It is worth saying clearly what is—and is not—true here.

Parker did not invent “heat” or the concept of central heating from scratch. Concepts and systems existed earlier in various forms.

What her patent demonstrates is an early, formal articulation of a natural-gas-powered, duct-distributed heating approach with multiple, individually controlled burner elements—a design logic that resonates with later developments in HVAC control and zoning.

This is how innovation often works. Someone proposes a workable grammar. Others write the later sentences.

Why Her Story Still Feels Contemporary

Parker’s patent is now more than a technical document. It is a cultural artifact: proof that Black women’s engineering imagination existed, persisted, and entered official record even when biography did not.

It is also a reminder of a recurring American dynamic: the country will adopt a Black person’s idea more easily than it will preserve a Black person’s life story.

The irony is sharpest in the heat itself. Modern HVAC is the kind of infrastructure people notice only when it fails. It is background comfort. It is invisible competence. Parker—whose documented life is nearly invisible—contributed to the conceptual direction of one of the most invisibly essential systems in American domestic life.

And perhaps that is the most fitting memorial available: a patent drawing that looks like a diagram of circulation—air moving through channels—when what we are really watching is history trying, belatedly, to circulate recognition back to its source.

What Responsible Reporting Can—and Cannot—Claim

A New York Times Magazine-style narrative thrives on scene, voice, and interiority. With Parker, an ethical approach requires a different kind of discipline: the scene must be built from verifiable context and primary documentation, not imagined dialogue.

Here is what we can say with confidence, supported by credible sources and primary materials:

A patent for “Heating-Furnace” was granted to Alice H. Parker on Dec. 23, 1919 (U.S. Patent No. 1,325,905).

The patent describes a gas-fueled system and includes drawings showing a multi-component design intended to distribute heated air.

Reputable institutional sources summarize her as a Black inventor associated with Morristown and with education linked to Howard University/Howard University Academy, while acknowledging limited surviving documentation.

Investigative reporting has documented widespread misattribution of photographs and conflicting biographical claims online.

Housing finance systems—particularly discriminatory lending practices—have constrained Black access to homeownership and home improvement capital, shaping who can retrofit, upgrade, and benefit from domestic technologies.

What we cannot responsibly do is fill in her inner life with invented detail. The point is not to make her story prettier. The point is to make it truer.

The Warmth We Inherit

If you live in a house with ductwork that turns rooms into choices—warmer here, cooler there—then you are living inside an old ambition: to make heat obedient.

Parker’s patent is a record of that ambition written in the language of her time: “economy of labor,” “greater flexibility,” “reliable and efficient.” It reads like someone who understood that comfort is not frivolous. Comfort is time. Comfort is safety. Comfort is the ability to sleep through a winter night without waking to tend a fire.

But it is also, inevitably, a story about who gets to buy comfort.

The bank customer—approved or denied, quoted a rate or refused a loan, offered a path to improve or told, quietly, to remain in place—becomes a character in the life of every invention that attaches to a home.

In that sense, Parker did not merely patent a furnace. She patented an idea about how life could feel inside the walls. The rest of the century became a long negotiation—technological, financial, and political—over who would be allowed to live there.