KOLUMN Magazine

The Space Between First and Forever

Inside the overlooked overlap of NASCAR’s two earliest Black competitors.

By KOLUMN Magazine

Bay Meadows Racetrack in San Mateo, California—better known for thoroughbreds than stock cars—hosted a kind of American improvisation, in late July 1955. NASCAR’s Grand National division was still young enough to treat geography like a suggestion. If there was a dirt oval and a paying crowd, the circus could arrive. That afternoon, among names that would harden into legend—Tim Flock, Lee Petty, Marvin Panch—there was a driver whose presence carried a different weight, and whose story would later need to be recovered like a mislaid document: Elias Bowie.

He drove a Cadillac, started deep in the field, and by the end had completed 172 of 252 laps—28th out of 34, an unglamorous line in a results sheet that would one day matter more than anyone in that grandstand could have predicted.

If you are looking for the moment NASCAR “integrated,” you might imagine a cinematic hinge: a tight shot of a helmeted face; the hush before an engine’s roar; a flagman caught between routine and history. But racing rarely offers history in clean close-ups. It offers it as logistics: who is allowed through a gate, who gets a credential, who can rent a room nearby, who can buy parts on credit, who gets waved down by a mechanic willing to touch their car. The more accurate picture of integration is a long, uneven process in which “first” is often less an event than a bureaucratic fact—easy to overlook, easy to miscredit, easy to bury.

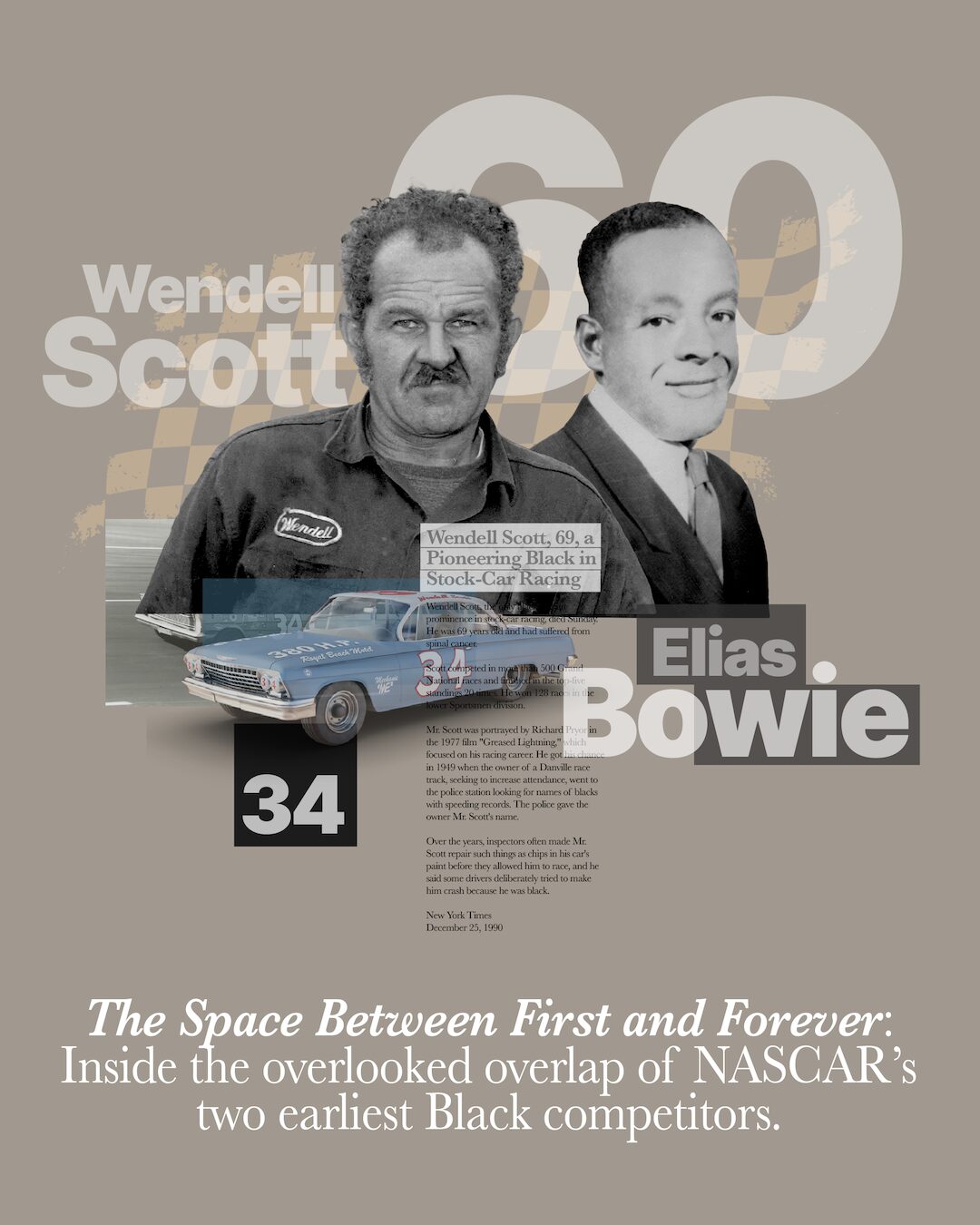

Elias Bowie’s start at Bay Meadows is now widely credited as the first by an African American in a top-level NASCAR race. Wendell Scott, meanwhile, would become the name the public remembers: the full-time striver, the Danville mechanic who hauled his own car, raced in the heart of segregation, and in 1963 won a premier-series race that officials initially refused to award to him in public.

Their careers overlapped in the way two storms overlap on a weather map: not necessarily by colliding, but by forming in the same atmosphere. Bowie and Scott were never teammates. They did not share a famous rivalry. They did not, as far as surviving reporting shows, swap stories over coffee in a garage. And yet their timelines do touch—most clearly in the early-to-mid 1950s, when Scott held a NASCAR license and was fighting for opportunity, and when Bowie successfully made it onto a Grand National grid. Their overlap is also conceptual: two men trying to enter a sport that treated Black participation as either an exception to manage or a problem to prevent.

A pioneer who looked like a rumor

Bowie’s story—at least the version that can be responsibly told from public documentation—has the shape of a half-lit life. NASCAR’s own recent historical reporting describes him as thrill-seeking, wide-ranging, and difficult to fit into a single archetype of “driver,” because he was also, crucially, a businessman with enterprises beyond the track.

That matters. In mid-century American racing, the car itself was often only the most visible expense. Entry fees, tires, fuel, parts, transport, and the time required to chase events across a region created a secondary contest: a contest of capital. Some drivers had sponsors and shop networks; others had their own hands and whatever they could borrow. If you could not secure backing—whether through formal sponsorship or the informal extension of trust that functions like credit—you were racing two fields at once: the competitors in front of you, and the scarcity behind you.

Bowie, per historical accounts and racing retrospectives, arrived at Bay Meadows with unusual support—one note about his appearance emphasizes the size of his pit crew. He was not simply a lone figure sneaking into a segregated space; he was a man with people around him, which implies organization, relationships, and resources. Some accounts also describe him as owning transportation businesses in the Bay Area—a detail that does not prove ease or immunity but does suggest a degree of financial and social infrastructure not available to many racers, and certainly not to most Black racers of the period.

And still: one NASCAR start. One top-level result. A name that could disappear from mainstream memory long enough for later narratives to declare someone else “first.”

The temptation is to interpret that single start as failure, or as a footnote. But the better lens is structural: in 1955, the obstacles facing a Black driver were not limited to whether he had talent. The obstacles were whether the sport could tolerate his visibility—whether promoters wanted him, whether competitors would accept him, whether a track’s informal power structure would permit him, whether the surrounding town could provide the basics of travel without humiliation or danger.

The United States, in that year, was a place where a man could be old enough to have lived through the First World War, the Great Depression, and the Second, and still be treated as a trespasser at a restaurant counter because of his race. Racing did not float above that reality; it ran straight through it.

A mechanic from Danville, a family on the road

If Bowie’s story is about a door opening briefly on the West Coast, Wendell Scott’s is about walking into the South and insisting the door exist at all.

Scott was born in Danville, Virginia, and became a mechanic—skills learned in part through his father’s work as a driver and mechanic. He started racing in regional circuits in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and public histories describe him as obtaining a NASCAR license in 1953—years before he was allowed a consistent presence in NASCAR-sanctioned events. That gap—between being “licensed” and being meaningfully welcomed—captures the sport’s posture: paperwork could be granted, but belonging could be withheld.

By the time Scott made his Grand National debut in 1961 at Piedmont Interstate Fairgrounds in Spartanburg, South Carolina, he was not arriving as a novelty. He was arriving as a seasoned driver who had already spent years learning how to race and survive.

Survival is not a metaphor here. Contemporary and retrospective reporting, including major features and biographies, documents the routine indignities and risks: Scott and his family being denied hotels and restaurants; a constant improvisation of meals, lodging, and safety; a sport culture where discrimination ranged from petty to violent.

And yet he kept showing up. Not because the institution wanted him, but because he wanted the work—and because work, for a mechanic-driver running his own operation, is also a kind of identity. He was both driver and team owner, competing against outfits with larger budgets and steadier pipelines of parts.

In that sense, Scott’s story reads like a traveling balance sheet: how far can expertise and stubbornness carry you when the market—sponsorship, equipment, hospitality—does not behave the same way for you as it does for others?

Where their careers overlap—time, sanction, and the problem of “first”

The cleanest overlap between Bowie and Scott is chronological and institutional, not spatial.

Scott’s NASCAR relationship begins early: histories note he obtained a NASCAR license in 1953, even as he faced refusals and detours that pushed him toward other circuits before his 1961 Grand National debut.

Bowie’s top-level NASCAR start occurs in 1955: on July 31, 1955, at Bay Meadows, he makes what is commonly identified as the first African American start in a top-level NASCAR race.

That means that in the mid-1950s, both men are within NASCAR’s orbit: Scott as a licensed racer fighting for access and track-by-track acceptance, and Bowie as a driver who—at least once—successfully entered the premier-series grid.

Did their careers overlap on the same track, the same weekend? The available public record does not establish that. Bowie’s documented premier-series participation is tied to Bay Meadows in California; Scott’s early NASCAR-era struggle and eventual breakthrough played out largely in Virginia and the Carolinas, then across the Grand National schedule once he became a regular. If there was a handshake, it is not preserved as a famous photograph; if there was a shared paddock, it has not survived as a widely cited anecdote.

But overlap is not only about proximity. It is also about sequence: Bowie’s 1955 entry precedes Scott’s 1961 debut, and yet the sport’s popular memory long treated Scott as the inaugural figure—an error that tells you something about which kinds of “firsts” institutions like to remember. Bowie’s story complicates the narrative because it suggests that the barrier was pierced earlier than the mythology admits—and then resealed by neglect.

Scott, by contrast, is remembered precisely because he stayed. He forced repetition. And repetition, in American public life, is often what turns an exception into a record.

The 1963 win—and the lesson in how history is administered

On December 1, 1963, Scott won a Grand National race in Jacksonville, Florida—his first and only victory at NASCAR’s top level. But officials initially declared another driver, Buck Baker, the winner, citing scoring confusion; Scott’s recognition came later, after a delay, and without the full public ceremony typically afforded a victor.

This episode has been revisited repeatedly because it is unusually legible. You do not need to be a scholar of race in sport to understand what it means to win, and then be made to wait for your win, out of public view. In some accounts, the delay is framed as a “scoring error”; in others, as an institutional choice meant to avoid the image of a Black winner receiving the usual Victory Lane celebration.

Decades later, Scott’s family was presented with a trophy connected to that 1963 victory—an act widely covered as long-overdue acknowledgement. The very fact that this became news tells you how incomplete the earlier moment had been.

What does this have to do with Bowie?

Everything, if you think of recognition as part of competition. Bowie’s 1955 start is one kind of recognition—permission to appear. Scott’s 1963 treatment is another—permission to be celebrated. In both cases, NASCAR’s story is not only about who drove fastest. It is about how an institution manages the visibility of Black achievement: sometimes by minimizing it, sometimes by misfiling it, sometimes by placing it in the past tense long before the people involved are finished living with the consequences.

Money, credit, and the quiet mechanics of exclusion

In any form of motorsport, the public tends to romanticize the obvious drama: the crash, the pass, the engine failure. Less visible are the practical systems that decide who can even attempt the drama. Scott’s career is widely described as a low-budget operation, often running used equipment against better-funded teams.

That funding gap is not incidental—it is the story’s spine. In a segregated economy, the same things that shaped Black entrepreneurship shaped Black racing: access to favorable deals, to parts pipelines, to sponsorship, to lodging, to vendors who would extend trust. Even the mundane act of travel—fueling up, eating, sleeping—became a negotiation.

Bowie’s background, as reported in racing retrospectives and in NASCAR’s own historical work, suggests a different relationship to that infrastructure: a man with business interests and, at least for one weekend, enough organization to field a conspicuous pit crew.

So one way to understand their overlap is this: two models of how a Black racer could appear in mid-century stock-car racing.

Bowie as the brief entry, a pioneering start that required enough support to make the attempt—and then, for reasons the record cannot fully specify, did not become a sustained NASCAR presence.

Scott as the endurance campaign, a multi-season insistence that created not just a first, but a body of work—495 premier-series starts and a record that could not be dismissed as a curiosity.

If you are searching for “personal narratives,” they are often hiding in these business facts: in the difference between a one-off entry with visible support and a long career built with scarcity.

The sport’s selective memory—and why it matters now

The contemporary press has repeatedly returned to Scott’s story not only as biography but as a diagnostic of NASCAR’s diversity problem. The Guardian, for example, frames Scott’s life as proof of how steep the sport’s “mountain” remains, decades later. The Washington Post has covered the slow process by which Scott has been publicly honored, including Hall of Fame recognition and the broader reassessment of his place in American sports history. The Root and other outlets have treated the belated trophy presentation as a cultural correction, not just a sports anecdote. Ebony, covering modern NASCAR milestones, repeatedly cites Scott as the benchmark—“the first since Wendell Scott”—which is another way of saying: the time between his win and the next comparable headline was itself a story. Word In Black’s Black History coverage includes Scott among lesser-known figures—an editorial choice that quietly admits how often even major barriers-breakers can become marginal in popular memory outside their niche.

Bowie’s recovery into the record—via NASCAR historical work, archival digging, and the resurfacing of race documentation—shows a different problem: the fragility of “first” when an institution has not invested in preserving it.

This is not merely a debate for trivia night. Being “first” changes what a person’s risk is understood to have meant. It changes how you interpret the courage of showing up. It changes how a family explains a life.

And it changes, too, how a sport explains itself.

Two men, one era, a shared undertaking

Imagine the American map as it looked from a racer’s perspective in the 1950s and 1960s. Not the neat interstate map, but the lived one: the towns where a Black family could not count on a motel vacancy sign; the garages where a mechanic might refuse service; the tracks where a promoter might sell your name on a poster but hesitate to let you stand in the winner’s circle.

Bowie’s Bay Meadows start sits on that map like a pin in unfamiliar territory: California, 1955, NASCAR still improvising its national reach. Scott’s career pins the South and its circuits—1940s and ’50s local racing, a 1961 top-level debut, a 1963 win, then seasons of grinding competitiveness in a series that could not fully decide whether it wanted him.

Their overlap is, finally, the overlap of two kinds of courage.

One is the courage to enter a space that does not expect you and may not remember you.

The other is the courage to keep entering until the space has to account for you—until the record books, the headlines, and the sport’s own conscience can no longer pretend you were a guest.

Bowie opened a door—briefly, and earlier than many fans realized.

Scott walked through what remained of it, again and again, until the hinges screamed.

And that is how change often happens in American sport: not in a single triumphant moment, but in the long argument between who shows up and who gets to be seen.