KOLUMN Magazine

The Places Where the Needle Drops First

Across Black America, record stores have long been more than retail—part listening room, part newsroom, part sanctuary. A tour through seven shops still doing the work.

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a good day inside a record store, the music is not background—it is evidence.

A familiar ritual plays out in different accents across the country. Someone steps in out of weather—summer glare, winter grit, the flat fluorescent hum of a strip mall—and slows their body down to match the pace of browsing. Fingers flip through tight rows of cardboard sleeves. A customer pauses, pulls a record halfway out, checks the label, checks the condition, checks the story they’re about to buy. Sometimes they ask a question that isn’t really a question: You got any Go-Go? Any old reggae 45s? Any Houston rap I can’t find online?

The answer, when it comes from the right shop, is never just yes or no. It’s a conversation. It’s genealogy. It’s local history told through catalog numbers and scuffed corners.

For decades, Black-owned record stores have served as a kind of infrastructure in Black cultural life: retail, yes—but also a public meeting place, an informal school, a talent pipeline, a bulletin board, a listening room, a living archive. The National Museum of African American History and Culture has described neighborhood record stores as spaces where community members—especially young people—gathered to listen, learn, and participate in the social world of Black music. And scholars of Black consumer culture have documented how, in the 1960s and 1970s South, Black-owned record stores functioned as “commercial public space,” where young customers congregated and where owners and patrons collectively shaped what music meant in everyday life.

Those functions matter again now, in an era when the convenience of streaming sits alongside a growing hunger for physical media, local expertise, and places that still feel human. Vinyl sales have surged over the past decade; record stores have multiplied in gentrified corridors and revived downtowns. But the resurgence has not automatically translated into ownership or security for Black retailers—who have long faced a different set of constraints: unequal access to capital, the fragility of commercial leases, and neighborhood change that can treat “culture” as a marketing asset while pricing out the cultural workers who made it. In Bed-Stuy, the owners of a beloved Black-owned shop were forced to move on short notice after their landlord gave them a week to vacate—a familiar modern twist on an old story.

This is a guided listen through seven Black-owned record stores—each with its own sound, each standing inside a specific local pressure system, each offering an argument about what a music store is for. Along the way: the Bronx’s reggae sanctuaries; Chicago’s multigenerational storefront persistence; a Cleveland shop that treats Black music education as mission; a Houston institution founded to serve Black music lovers and still insisting, three decades later, on the value of the tangible artifact.

These stores are not interchangeable. They are, in the deepest sense, local. What connects them is a shared logic: that music is not only something to consume, but something to hold—and that holding requires stewards.

Before playlists, there were counters

In the popular imagination, record stores are often remembered as lifestyle scenery: crates, posters, cool clerks, an aesthetic of discovery. For Black communities, record stores have also been practical institutions—places where you could reliably find what mainstream outlets ignored, where imported music arrived, where local scenes announced themselves, where the new single was not just heard but debated.

The Smithsonian’s framing is explicit: record stores in African American neighborhoods were social spaces, where young people especially came together to listen and purchase music, and where record store culture helped shape taste and community identity. In the 1960s and 1970s South, as one academic account notes, Black consumers “flocked” to Black-owned record stores; patrons remembered them as community areas—places where “everybody knew everybody.”

That “everybody” is not nostalgia—it’s a business model and a cultural method. The stores built customer bases by knowing their customers: what they played at cookouts, what they played in cars, what they played when they needed to grieve or celebrate. They also built a record of demand—sometimes literally, through what sold—at a time when the rest of the market often treated Black music as niche, local, or disposable.

The seven shops featured here sit downstream of that history. Some were founded decades ago; others are comparatively new, created as acts of preservation and possibility. All of them operate in a present where music can be “everywhere” and still feel oddly absent—where the algorithm offers infinite choice but rarely offers the sensation of being seen.

Black Star Vinyl (Bedford–Stuyvesant, Brooklyn): a move, a renaming, a message

The storefront life of a small business in New York is often narrated as hustle and romance. But landlords write the plot.

Black Star Vinyl, the Bed-Stuy shop formerly known as Halsey & Lewis, is one of those places that feels like it has always existed: records, books, coffee, giftable objects; a curated interior that invites you to linger. Its story, however, includes a compressed lesson in urban precarity. In 2021, after years in one location, the shop’s owner was given a week’s notice to move out of the space—an abrupt displacement that would have killed a less networked business.

The shop resurfaced in a new location, and in 2022 it took a new name: Black Star Vinyl—an intentional homage that, as Brooklyn Magazine reported, arrived after the owners reopened the shop and then renamed it. The Amsterdam News later described the renaming as a tribute to Marcus Garvey’s Black Star Line, and reported that community support helped make the relocation possible.

The details matter because the name is not branding fluff; it is a declaration of lineage. In a neighborhood where Black cultural presence has been both celebrated and commodified, the name “Black Star” reads like a stake in the ground: a reminder that Black mobility, Black enterprise, and Black self-determination have always been contested—and that even a record store can choose to speak in that language.

A customer here might come for a specific pressing—jazz, soul, global music, an out-of-print title—but the longer they stay, the clearer the store’s other product becomes: permission to slow down. The shop is built to support that. It does not rush you toward a register. It invites a kind of browsing that streaming has nearly erased: the nonlinear pleasure of encountering something you didn’t know you needed.

And there is an additional, quieter function: Black Star Vinyl is a neighborhood proof-of-life. It suggests that a Black-owned cultural business can still anchor a changing Brooklyn block—not as a relic, but as a living place with a future.

Moodies Records (The Bronx): reggae as a borough language

If you want to understand how a diaspora builds continuity, spend time where it shops for sound.

Moodies Records, long associated with the Bronx’s Caribbean and reggae communities, has been described as a “cornerstone” of Jamaican/Caribbean culture in the borough. The Jamaica Gleaner reported that the shop—founded by Jamaica-born Earl Moodie on White Plains Road—became a sanctuary for reggae lovers and vinyl collectors, a place where generations went looking for “the soul of Jamaican sound in New York City.”

Accounts differ on the exact founding year in public references—an example of how community institutions can outgrow clean timelines—but multiple sources place the store’s origins in the early 1980s and emphasize its decades-long presence. Moodies’ own site describes it as a Bronx landmark “since 1981.” A Bronx Ink feature, written in the context of record shop closures, captures the store as a persistent local institution in the face of shifting retail realities.

What makes Moodies more than a store is the role it played as cultural supply chain. For customers, it wasn’t simply a matter of buying music; it was a matter of buying access: to imported records, to dancehall and reggae catalogs that mainstream outlets didn’t prioritize, to the artifacts of a culture that needed physical objects to travel well.

The Bronx Ink reporting frames Moodies as a surviving node in a disappearing ecosystem of record stores, and it hints at a generational transfer: the sense that customers come not only for themselves but for the continuity of a community’s listening habits.

In that way, Moodies is not just retail. It is an address where the borough’s Caribbean history can be heard.

JB’s Record Lounge (Atlanta): a lounge is a thesis

Some record stores insist, through their layout alone, that listening is a social act.

JB’s Record Lounge in Atlanta is publicly listed as Black-owned through Record Store Day’s store directory, which provides its West End address. Even the name—Record Lounge—signals a proposition: the point is not only to purchase, but to gather; not only to acquire, but to hang out long enough for recommendations to become relationships.

This “lounge” logic has deep roots in Black music retail, where the store served as a social room for young people, where conversation functioned as education. The Smithsonian’s account of neighborhood record stores emphasizes exactly that kind of communal learning environment.

In practical terms, the lounge model also responds to the streaming era. If almost any song can be accessed instantly, the differentiator becomes context: the chance to hear something on a system you trust, to be guided by a curator with taste, to meet other people who have built their lives around music.

The survival strategy here is subtle: make the store a place you can’t replicate online.

Home Rule (HR) Records (Washington, D.C.): music as autonomy practice

In Washington, D.C., the name “Home Rule” carries a political charge. It is the shorthand for a city still negotiating its autonomy, its representation, its power.

HR Records—the Black-owned shop in Brightwood Park—leans into that meaning. A Smithsonian Folklife feature reports that owner Charvis Campbell chose the name Home Rule Records (HR for short) in direct reference to the District’s lack of autonomy. That choice turns the store into a kind of civic text: music retail as commentary on governance.

Public reporting has also placed HR Records among a relatively small number of Black-owned record stores nationally. A WJLA feature notes the rarity of Black ownership in the record store world and profiles Campbell as an owner-operator building a community institution. (WJLA) The Washington Post, in a “dream day” feature, similarly describes HR Records as one of only a few dozen Black-owned record stores in the country and situates Campbell’s work as a form of education through music.

The inventory here is not neutral: jazz, soul, R&B, Go-Go—genres that map onto D.C.’s cultural DNA. The store’s website positions it as a brick-and-mortar shop specializing in those traditions.

But the deeper story is about what the store provides: a place where the District’s Black music history is treated as central, not peripheral. In a city shaped by churn—new residents, new developments, new narratives—the store acts as a stabilizer. It offers continuity not by resisting change outright, but by insisting that change must still make room for the archive.

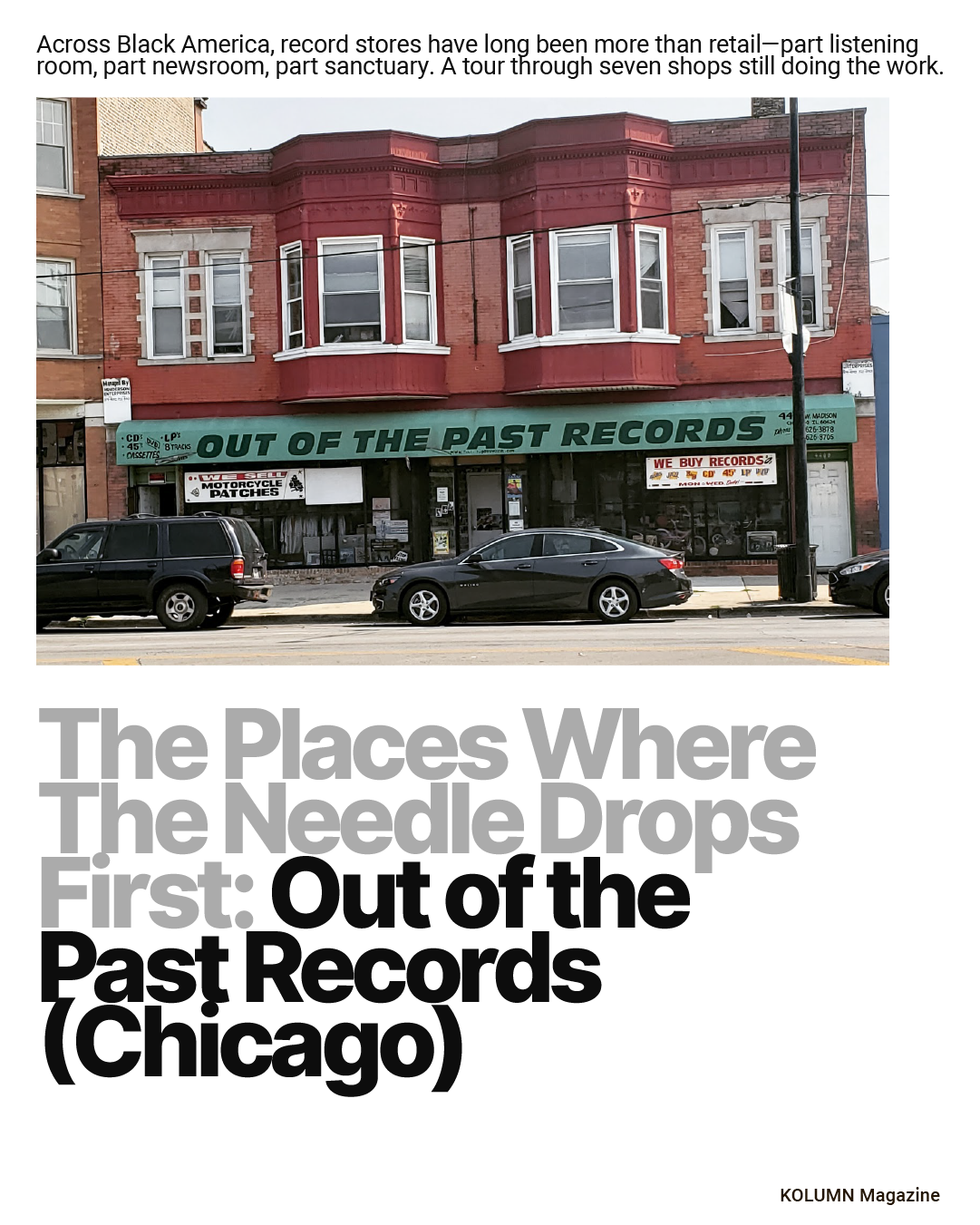

Out of the Past Records (Chicago): staying as a form of authorship

Chicago’s Out of the Past Records is a reminder that longevity is not only endurance; it is labor—daily, unglamorous, and often under-credited.

The shop is widely described as a West Side institution. Its own website invites customers into a broad-format music universe—vinyl, CDs, cassettes, posters—anchored by a physical address on West Madison.

A WTTW News feature framed Out of the Past as a family-owned record store open since the 1960s, focusing on how the business adapted over time—including the work of modernizing inventory systems and bringing operations into the digital era. That story matters because it undercuts the stereotype of “old” stores as frozen in amber. The store survives by changing, by updating its methods while keeping its purpose intact.

More recent reporting in the Chicago Sun-Times adds an additional layer: the moral and emotional reality of staying put in a neighborhood shaped by violence and disinvestment. In that piece, owner Marie Henderson is quoted resisting the logic that she should have to leave a place where she owns property and pays taxes—an argument that turns “small business” into a claim about civic belonging.

Out of the Past is, in other words, a record store that also functions as neighborhood testimony: a business that holds music, and in holding music, holds a version of Chicago that refuses to be erased.

Re-Runz Records (Orlando): the collector as caretaker

In Orlando, Re-Runz Records reads as a life’s accumulation turned outward.

The store’s website identifies the business as located on North Orange Blossom Trail. Its online materials describe a wide inventory that extends beyond vinyl—CDs, cassettes, posters, magazines—an ecosystem of media that treats music as physical culture.

The most revealing portrait comes through local reporting. Bay News 9 profiled owner Ed Smith as both a record store operator and a lifelong collector—someone who has listened to vinyl since his teens and played in jazz bands across decades. In that framing, the store is not simply a shop; it is a distillation of a life spent tracking sound.

The store’s “About” page reinforces the long-view relationship to collecting, describing Smith’s decades of acquiring music and his broader music-related projects.

Re-Runz is a reminder that record stores are often built from obsessive care. The “inventory” is not a supply chain abstraction; it is someone’s time, someone’s taste, someone’s memory—organized into bins so strangers can discover it.

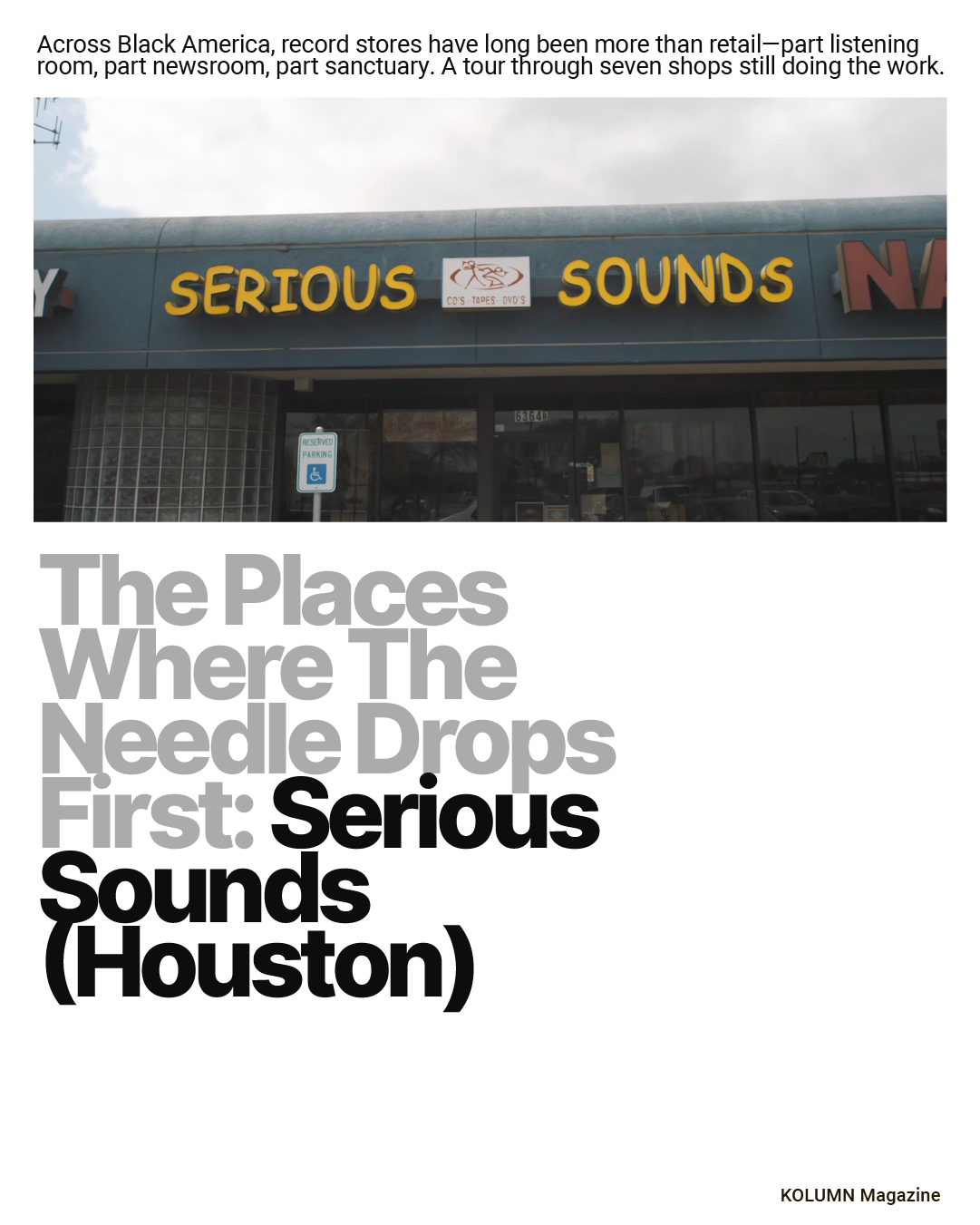

Serious Sounds (Houston): a thirty-year insistence

Houston is a city with a massive musical footprint—blues, gospel, jazz, Southern rap, chopped and screwed—and Serious Sounds, Etc. has been described as a rare Black-owned retail institution inside that landscape.

Women in Vinyl profiled founder Marketta Rodriguez and reported that she established Serious Sounds, Etc. in 1991 to provide a retail environment catering to African-American music lovers, marking the business’s 30th anniversary in 2021. The same profile notes a later transition away from a long-running physical location into an online-only model while searching for a new brick-and-mortar home—an adaptation that reflects the broader pressures of retail survival.

The store’s public-facing identity emphasizes its founding year and local pride; its social presence calls itself a real record store, established in 1991.

What makes Serious Sounds particularly resonant is the clarity of its founding purpose: a store built because the community needed one, because mainstream retail did not reliably serve Black musical demand on Black terms. That logic echoes the older history documented by scholars of Black music retail: Black-owned stores as sites where Black consumers shaped commercial and cultural public space.

In a city that builds new constantly, Serious Sounds represents the value of staying with the archive long enough for it to become intergenerational.

What these stores are really selling

It is tempting to romanticize record stores as “vibes,” to talk about wax and warmth and analog authenticity. But the deeper truth is more practical: these stores sell curation and care in a market that often undervalues both.

They also sell something else: a chance to be part of a living local tradition. In the Smithsonian’s framing, record stores were places where community members gathered and youth learned how to listen; in the academic record, Black-owned shops functioned as social infrastructure in a segregated economy.

In 2025, the threats look different—rent spikes, redevelopment, online competition, the instability of small retail—but the core problem remains familiar: the market does not automatically protect cultural institutions, even when it profits from the culture.

That is why the survival stories of these shops matter. Black Star Vinyl’s forced move and renaming is not merely a colorful anecdote; it is a case study in how fragile “place” can be, and how much community mobilization it can take to keep a place alive. Out of the Past’s insistence on staying is not just personal stubbornness; it is a civic argument about who is entitled to remain. Serious Sounds’ pivot to online is not a defeat; it is a survival tactic that keeps an institution intact while it searches for a sustainable physical footprint.

And then there is the customer—the person whose life becomes slightly more coherent because the right record was found at the right moment, because someone behind the counter cared enough to ask a follow-up question. Those stories are the least quantifiable, and they are the point.

The algorithm can predict your taste. It cannot replace the feeling of being known.

The Crate-Digger Guide: 7 Black-Owned Record Stores to Visit, Support, and Learn From

Black Star Vinyl (Brooklyn, NY)

Address: 480A Madison St, Brooklyn, NY 11221

Phone: (347) 262-4358

Best for: A “stay awhile” shop—records plus a calm, community feel (and coffee).

Ask for: “What’s the one record you’d hand someone who says they’re ‘trying to get into’ jazz/soul?” (Let them curate your entry point.)

Moodies Records (Bronx, NY)

Address: 3777A White Plains Rd, Bronx, NY 10467

Phone: (718) 654-8368

Best for: Reggae, dancehall, and the Bronx’s Caribbean listening history—deep catalog energy.

Ask for: “What’s the record that best explains this neighborhood’s reggae taste?” (You’re requesting Bronx context, not just a title.)

JB’s Record Lounge (Atlanta, GA)

Address: 898 Oak St SW, Suite F, Atlanta, GA 30310

Phone: (404) 228-3510

Best for: Daytime digging with a neighborhood “lounge” vibe—more hang than transaction.

Ask for: “What’s your best ‘Atlanta lineage’ run—three records that trace the city’s sound from then to now?”

Home Rule (HR) Records (Washington, D.C.)

Address: 702 Kennedy St NW, Washington, DC 20011

Phone: (202) 469-9868

Best for: Rare and used jazz, soul, Go-Go, reggae/African records—serious digging with D.C. DNA.

Ask for: “If I want one Go-Go record that explains D.C. to a newcomer, what’s the move?” (They’ll usually give you a history lesson with your purchase.)

Out of the Past Records (Chicago, IL)

Address: 4407 W Madison St, Chicago, IL 60624

Phone: (773) 626-3878

Best for: Long-running West Side institution energy—bins that reward patience.

Ask for: “What sells here that wouldn’t sell in a North Side shop?” (You’re asking for West Side taste and the store’s real specialty.)

Re-Runz Records (Orlando, FL)

Address: 6325 N Orange Blossom Trail, Ste 125, Orlando, FL 32810

Phone: (321) 239-6325

Best for: Wide-genre community record hunting—new and used, the kind of place you browse twice.

Ask for: “What’s the best Florida-to-the-world record in the store right now?” (You’re inviting local pride picks.)

Serious Sounds, Etc. (Houston, TX)

Address: 6364 Martin Luther King Jr Blvd, Houston, TX 77021

Phone: (713) 738-8273

Best for: A long-running Black-owned Houston institution (est. 1991) with deep community roots.

Ask for: “What record best represents Houston’s sonic identity, not just Texas?” (This tends to unlock a real conversation.)