KOLUMN Magazine

The Hill

We Keep Climbing

A new children’s biography arrives as “The Hill We Climb” remains a civic text, a mirror held close, and a reading lesson.

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a winter display table—between a cartoon puppy learning to share and a brightly illustrated introduction to a civil-rights icon—sits a slim paperback that attempts a delicate translation job. It is not trying to teach the subjunctive mood or the long “a” sound, not exactly. It is trying to teach Amanda Gorman.

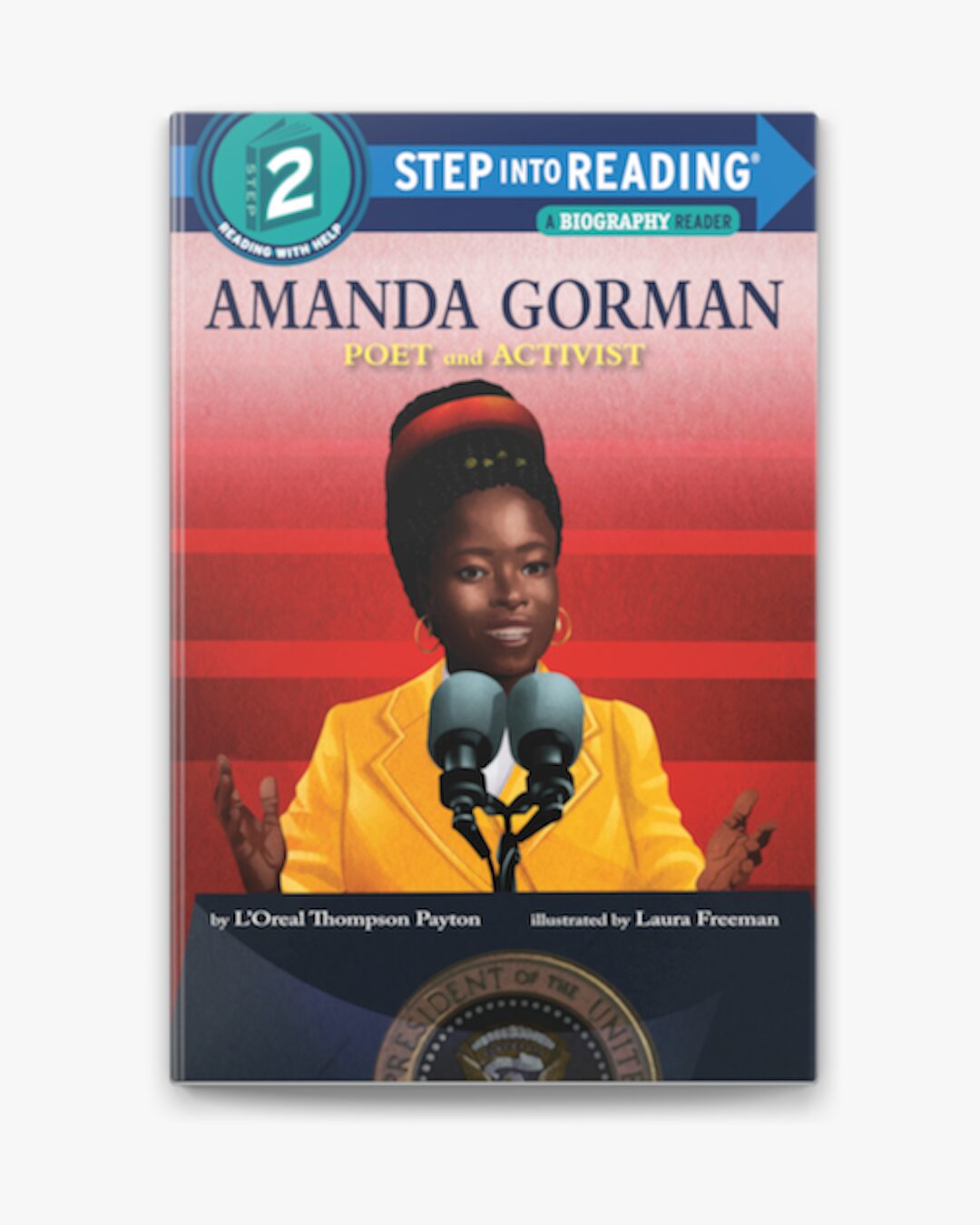

The title is direct, almost instructional: “Amanda Gorman: Poet and Activist (Step into Reading).” It belongs to a long-running American publishing institution designed for the first years of independent reading—short sentences, controlled vocabulary, a sense of forward motion that rewards a child for turning the page. Penguin Random House describes this volume as a “Step 2 reader,” meant to introduce children to Gorman’s life: obstacles overcome, a voice discovered, a public moment that made her the youngest inaugural poet in U.S. history.

That table—at a bookstore, at a library book sale, at a scholastic fair—has become one of the country’s quiet battlegrounds. Over the last several years, adults have argued not only about what children should read, but about what reading means: whether the classroom is a civic workshop or a protected space, whether literature is a mirror or a provocation, whether words meant to unify can be recast as “indoctrination.” In 2023, the debate found Gorman directly when her inaugural poem “The Hill We Climb” became entangled in a school restriction controversy in Florida, with national coverage, competing claims about what “banned” means, and a familiar churn of outrage.

So there is a particular irony—maybe even a kind of American symmetry—to seeing Gorman arrive, now, in a format that has historically been among the least controversial in the culture: the early reader. According to retail listings, the book’s publication date was December 16, 2025, under Random House Books for Young Readers, and it is credited to L’Oreal Thompson Payton with illustrations by Laura Freeman.

The question the book inevitably raises is not whether a child can read it. The question is what happens when a figure who rose through a national moment—through television, politics, and the pressure of history—gets distilled into the clean lines of beginner nonfiction. What gets preserved, what gets simplified, and what we reveal about ourselves by insisting that one version of the story is safe.

A life made legible

The Step into Reading model is built around the idea that confidence is cumulative: read one sentence, then the next; learn a new word; feel capable. Biographies in the series often follow an arc that is almost moral in its architecture: a child shows early curiosity, meets difficulty, finds a gift, uses it in the world.

Gorman’s story fits that arc—up to a point—because it is, in part, a story about language as a tool for self-making. Penguin Random House’s description emphasizes that she “overcame obstacles through poetry” and committed herself to helping young people find their voices, culminating in her inauguration reading in 2021.

But “obstacle” is doing a lot of work in that sentence. In adult profiles and interviews, Gorman has described challenges with speech and auditory processing in childhood and how she practiced to become a performer whose voice could carry. Long before her inauguration, she was already a public-facing poet—she was named the first National Youth Poet Laureate in 2017, and she had built a persona that could move between literature, civic life, and the modern attention economy. PBS’s Amanpour and Company has framed her as a young activist as well as a writer, highlighting the unusual scale of her early accomplishments.

What early-reader biography can do well is introduce the shape of that journey—help a child understand that writers come from somewhere, that art has a biography, that a poem does not fall out of the sky. What it cannot do—what it is not meant to do—is fully explain the historical compression that made Gorman’s ascent feel less like a career and more like a national event.

Gorman became famous the way very few poets do: not slowly, through journals and graduate seminars and a thin audience of initiates, but suddenly, on broadcast television, at the hinge point of a country’s self-narration. Her performance was immediately interpreted as symbol—a new generation, a new tone, a promise of civic repair after the trauma of January 6. Reuters described the poem as capturing a United States “bruised, but whole,” noting the timing: an inauguration occurring in the shadow of the Capitol riot.

In other words, the Step 2 reader is not simply teaching about Amanda Gorman. It is teaching about what America decided Amanda Gorman was.

The performance that turned a poem into a public artifact

To understand why this children’s biography matters, you have to return to the moment it is built around: January 20, 2021. The country was still in the pandemic’s long breath. The Capitol still held the after-image of violence. The inauguration was staged as both ceremony and counterspell—an attempt to replace chaos with ritual.

Gorman’s poem did what good public poetry has always done: it scaled private language to public use. It gave the audience phrases that could be repeated—lines that sounded like they belonged not just to one poet, but to the collective mouth. The Washington Post, reflecting on the performance days later, argued that her delivery made poetry feel newly vital to the ceremony, emphasizing the dynamism of her spoken-word craft.

This is one of the hardest things to translate for young readers: the difference between a poem on a page and a poem in a room. In the adult world, that difference is often where power lives. Gorman’s reading was a performance in the old sense—voice, gesture, rhythm, timing—and in the new sense: a moment designed to travel through clips, memes, and fashion coverage.

The Step into Reading book, by necessity, focuses on the headline fact—she read a poem at the inauguration—but the cultural story is more complicated. Her presence became a kind of national shorthand for unity, youth, Black brilliance, and institutional redemption. That burden is flattering, and it is also heavy. It asks a poet to become a civic mascot.

Which brings us to the poem itself—and to why it deserves an expanded examination even in a story about a children’s biography.

The Hill We Climb, close up

The opening line of “The Hill We Climb” begins as a question, as if the poet is checking whether the audience is ready to admit what it has lived through: “When day comes we ask ourselves, where can we find light in this never-ending shade?”

The line is a diagnostic tool. It acknowledges darkness without surrendering to it. It also establishes one of the poem’s central tactics: to take the language of national myth—light, dawn, shade, hill—and use it as both comfort and critique.

The poem’s architecture: from rupture to repair

Structurally, “The Hill We Climb” is built like a walk-through wreckage that refuses to end in despair. It holds two realities at once: the country’s aspiration and its violence. The poet names a nation that “isn’t broken but simply unfinished,” a framing that allows for accountability without nihilism. (This idea, widely paraphrased in commentary, became part of the poem’s popular afterlife.) Reuters, in its contemporaneous report, emphasized how the poem spoke to recent national injury while insisting on forward motion.

One way to read the poem is as a series of turns—moments where the speaker shifts from observation to instruction, from elegy to imperative. It moves through a catalogue of American contradictions: democracy as promise; democracy as practice; democracy as performance; democracy as work.

The poem’s most quoted lines tend to function as civic slogans—portable hope. But the poem is also full of more complicated gestures: acknowledgments that unity is not a mood but a discipline, that “coming together” without truth is simply another form of avoidance. In that sense, “The Hill We Climb” is less a celebration than a plan—a blueprint for moral stamina.

The shadow in the poem: January 6 as a haunting

The poem is often remembered as a bright thing, but it is bright because it is written against a dark wall. Its context is explicit: the Capitol attack was not an abstraction; it was a scene still fresh in the national nervous system. Gorman refers to a force that “would shatter our nation” rather than share it. That language works like a warning label: this is what the country has just survived, and what it could still become.

In commentary, critics noted that the poem contains familiar American rhetorical tropes—calls for healing, invocations of light—but argued that Gorman’s performance and specificity elevated the material beyond cliché. That tension—between “generic Americanism” and lived immediacy—is part of the poem’s technique. Public poems often have to be slightly generic in order to be widely owned. They also have to be specific enough to feel earned.

Gorman does this by grounding her lofty language in the tangible: the Capitol, the “hill,” the sense of a nation stepping “out of the shade.” These are not merely metaphors; they are stage directions for a country trying to re-enter its own story.

The refrain of rising: geography as a democratic chorus

One of the poem’s most resonant passages is a sequence of “we will rise” lines that map hope onto the country’s regions, as if unity could be practiced by naming. “We will rise from the golden hills of the West… from the windswept Northeast… from the lake-rimmed cities of the Midwestern states… from the sunbaked South,” the poem declares, before arriving at verbs that sound like policy goals and spiritual commitments at once: “rebuild, reconcile, and recover.”

This passage matters for a children’s biography because it reveals how Gorman makes civic belonging feel concrete. Kids understand maps. They understand “where we live.” The poem converts geography into a chorus—an argument that the national “we” is not an abstract pronoun but a sum of places and people.

It is also a subtle reversal. The country often uses regional stereotypes to divide itself—red state, blue state; coast, heartland; urban, rural. Gorman’s geography collapses those categories into a single motion: rise. The poem implies that the nation’s regions are not competing identities but shared responsibilities.

The poem’s moral proposition: patriotism as repair work

One of the most quietly radical lines in the poem reframes patriotism not as inheritance but as labor: “Being American is more than a pride we inherit… it’s the past we step into and how we repair it.” The Washington Post highlighted this framing as part of the poem’s insistence that the American idea is a process, not a static object.

For adult readers, the line is a political philosophy. For young readers—especially those encountering Gorman through a simplified biography—it can be a formative ethic: love as responsibility, not sentiment.

This is where the Step into Reading biography becomes more than a product. It becomes an early encounter with a civic posture. The book is not merely saying, “Here is a famous person.” It is, implicitly, saying, “Here is one way to belong to a country.”

The poem’s afterlife: admiration, commodification, resistance

Public poems have afterlives. They get quoted at graduations and printed on posters and posted in classrooms. They also get turned into objects—books, merchandise, marketing hooks. That is not new. What is new is the speed and scale at which a poem can be absorbed into brand culture.

Gorman’s visibility made her an emblem, and emblems attract projection. For some, she represented a generational shift; for others, a threat—another sign that the cultural center was moving away from them. That fracture helps explain why “The Hill We Climb,” a poem explicitly designed to be unifying, later became a target in school-content conflicts.

Word In Black framed the Florida controversy as part of a broader pattern of anti-Blackness in educational censorship debates, emphasizing how a single complaint can ripple outward into national consequence. PEN America, responding at the time, described the removal/restriction as stemming from one parent complaint and situated it within a larger climate of book challenges.

It is worth being precise: reporting and fact-checking at the time distinguished between a districtwide “ban” and a change in access (for example, moving a title to middle-grade availability). But the semantic fight—banned versus restricted—can obscure the practical truth: the poem became contested territory, and Gorman became one of the names attached to that contest.

That tension shadows any new Gorman-related children’s title. The Step into Reading biography arrives into a world where her work is both widely celebrated and intermittently policed.

The “new book” question: what this Step into Reading title is—and isn’t

It is easy, in the slipstream of celebrity publishing, to assume that every new book with a famous name on the cover is authored by the famous person. But “Amanda Gorman: Poet and Activist” is a children’s biography written by L’Oreal Thompson Payton and illustrated by Laura Freeman, positioned explicitly as an early reader.

That distinction matters because it changes what the book is trying to do. This is not Gorman’s latest poetic statement; it is a curatorial project—an attempt to tell a coherent origin story using the tools of beginner nonfiction. It is a book that functions less like literature and more like introduction.

According to the publisher description, its goals are clear: tell children how Gorman used poetry to overcome obstacles; show her commitment to helping young people find their voice; explain the milestone of the 2021 inauguration.

The “Step 2” label also matters. These books are built for a child who is transitioning from being read to, into reading alone—short sentences, basic vocabulary, a strong reliance on illustration to carry complexity. The biography is, in a way, a scaffold: it supports the reader while the reader becomes capable.

The illustrator’s role: translating history into image

In books for early readers, illustrations are not decoration. They are narrative engines. In a standard adult profile, Gorman’s inaugural outfit can become a fashion footnote, a symbol of intention. In a children’s biography, the yellow coat, the red headband, the podium: these become the visual anchors that tell the reader, this happened; she stood here; the world watched.

That image—the young Black woman at the lectern—has already become one of the most recognizable cultural photographs of the decade. And it is, for better or worse, the image through which many children will first encounter her.

What gets simplified—and what stays sharp

Any biography for five-year-olds is a negotiation with complexity. You cannot include everything. You cannot explain every political nuance. You have to choose the shape of the story.

The danger, of course, is that simplification can become sanitization: a story where “activist” becomes a vague label rather than a practice, where the nation’s conflict disappears, where the poem is treated as a magic spell rather than a crafted response to a particular rupture.

And yet there is also an ethical case for introductions. Children live in the country adults are building. They deserve language for it. They deserve models of voice.

This is the tightrope the book walks: it tries to honor a figure whose work is rooted in history without dragging a child into the most corrosive adult arguments about that history.

The readers around the book: teachers, librarians, and the new front line

In recent years, the people who choose books for children—teachers, librarians, booksellers, parents—have been pushed into a more public role. Selection has become a kind of speech. A purchase order can feel like a political act. A display can feel like an argument.

When Gorman’s inaugural poem became controversial in a Florida district, it demonstrated how quickly a text can be turned into a test of institutional courage—and how quickly the adults closest to children can be forced into crisis management. The Washington Post reported details from committee notes and district responses that framed the restriction as a process decision, while critics framed it as censorship.

Ebony’s coverage described the episode in more explicitly political terms—placing it within Florida’s broader climate of “anti-inclusionary” rhetoric and legislation. The Root, in its characteristically blunt voice, emphasized the emotional impact Gorman described—what it feels like to have a poem meant to inspire hope treated as dangerous.

These aren’t academic distinctions to a school librarian deciding what goes on the shelf. They shape how a community understands the librarian’s job: educator or gatekeeper, caretaker or provocateur.

A Step into Reading biography about Gorman is, in that context, almost a quiet provocation—not because it is radical in content, but because it insists that her story belongs in the earliest layers of literacy. Not later, not as an elective, not once you are old enough to argue about it. Now, while you are still learning how to sound out words.

A broader Gorman universe: children’s publishing as a strategy of access

Even apart from controversy, children’s publishing has been one of the most important vehicles for Gorman’s cultural reach. In public interviews about her children’s books, she has emphasized a desire not to condescend to young readers—to treat them as capable of complexity and worthy of serious language. In a recent profile tied to her picture book Girls on the Rise, People reported Gorman’s focus on building a “welcoming dialogue” with kids and her belief that children can grapple with big themes when approached with respect.

That sensibility aligns with what makes “The Hill We Climb” work: it is accessible without being small. It speaks plainly, but it does not speak down.

The Step into Reading title is not written by Gorman, but it participates in the same ecosystem: books as access ramps. A child who meets her through a Step 2 biography might later meet her through a picture book, then a performance clip, then the poem itself.

In that sense, “Amanda Gorman: Poet and Activist” is part of a longer educational pipeline—one that treats poetry not as a rarefied genre but as a public form, and treats a poet not as an eccentric specialist but as a recognizable kind of American figure.

The tension inside “activist”: what the word demands

The children’s biography uses the word activist as a defining descriptor. That word can be fuzzy in adult conversation; in a child’s book, it can become almost purely positive: someone who helps people, someone who cares.

But activism has stakes. It involves conflict. It names a decision to push against something—law, policy, tradition, silence. When you call a poet an activist, you are making a claim about what language is for.

Gorman’s life has supplied plenty of activism-adjacent facts—public engagements, speeches, partnerships, and a career shaped by civic performance. Recently, People reported that UNICEF named her an ambassador, emphasizing her advocacy for children and her role in using poetry to raise awareness.

Those affiliations reinforce the biography’s framing. But they also raise the question a good magazine story should ask: what kind of activism does the public want from a poet? The safe kind—uplift, unity, inspiration—or the dangerous kind—naming harm, demanding repair, refusing comfort?

“The Hill We Climb” is often read as an inspirational poem, but it is also a poem that insists on historical reckoning. Its hope is not naïve; it is conditional. It requires courage. It requires work. That is a more demanding lesson than most children’s books attempt to teach, and it is precisely why the poem remains relevant.

What this moment asks of us

There is a temptation to treat a Step into Reading biography as a minor cultural event—one more children’s title among thousands. But in the case of Amanda Gorman, minor objects often become major signals.

This book’s existence suggests a bet being made by children’s publishing: that Gorman is not merely a viral moment or a political symbol, but a durable figure in the story the culture tells to children about what language can do. It suggests that her inauguration reading was not simply entertainment or ceremony, but a civic artifact worth archiving at the level of first literacy.

And it suggests something else, too: that the adults who fight about books have, inadvertently, reinforced the importance of books.

Because when a nation argues about whether a child should have access to a poem, it is also admitting—however bitterly—that words matter. That language can shape identity. That stories can move policy. That a slim paperback, placed at eye level, can become a kind of power.

The Step into Reading biography does not resolve those arguments. It sidesteps them, as it must. But it arrives carrying the echo of the poem that made Gorman famous—a poem that ends not with triumph but with instruction: that there is light, yes, but only if we are brave enough to see it, and brave enough to be it.

For a child sounding out sentences, bravery might mean finishing a page alone. For the adults choosing which pages children are allowed to see, bravery might mean something else entirely.

Amanda Gorman: Poet and Activist

By L’Oreal Thompson Payton, Illustrated by Laura Freeman