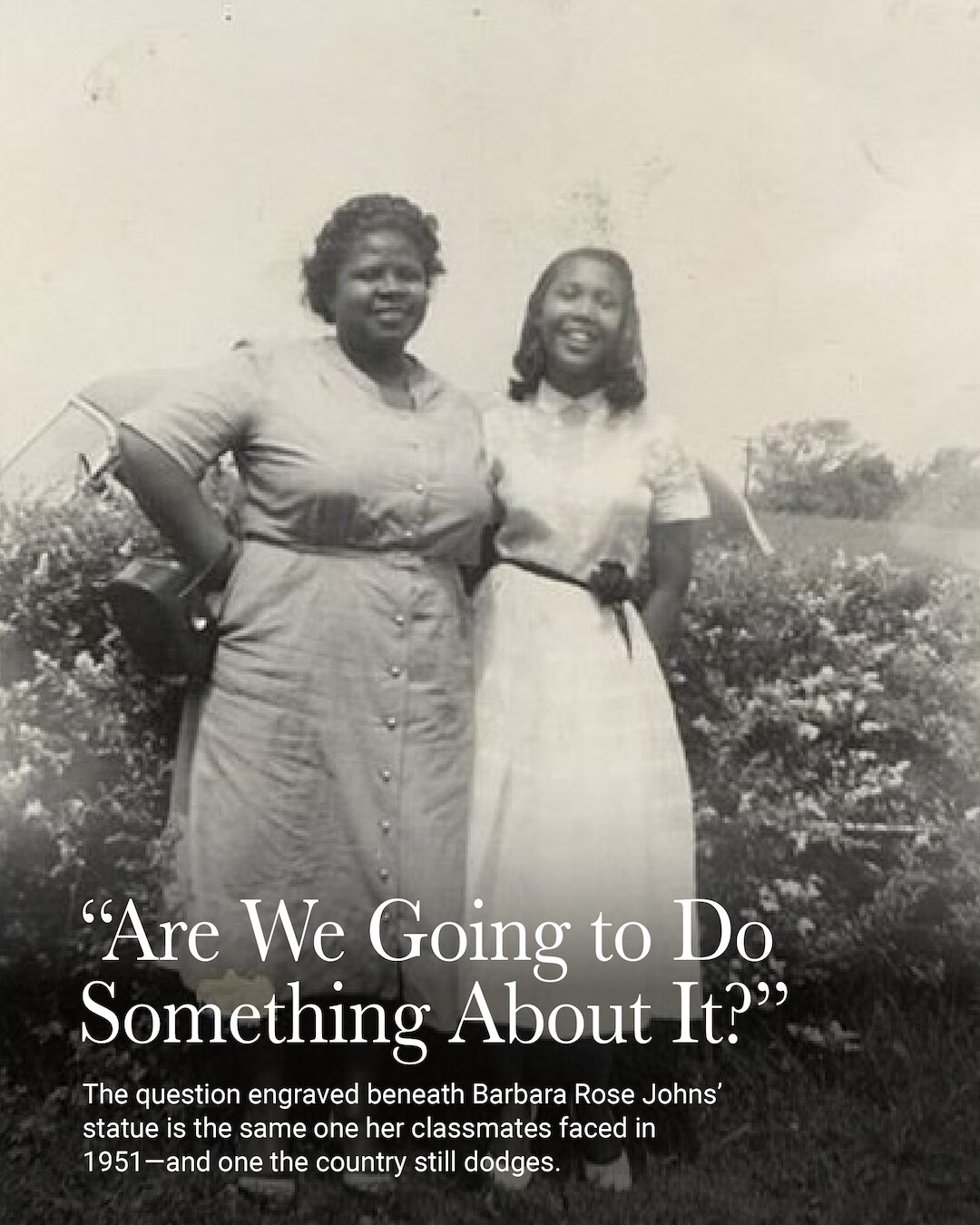

“Are We

Going to Do Something About It?”

The question engraved beneath Barbara Rose Johns’ statue is the same one her classmates faced in 1951—and one the country still dodges.

By KOLUMN Magazine

In Washington, monuments tend to announce certainty. They reassure. They settle the matter.

So it is a jolt—almost a rebuke—to meet a statue that does the opposite: it asks. The new figure representing Virginia in the U.S. Capitol is not a president, a general, or a statesman with a sealed fate. She is a high school junior. She is 16. She is mid-speech. One arm is lifted, holding a battered book overhead like evidence.

The pedestal carries her question: “Are we going to just accept these conditions, or are we going to do something about it?”

The “conditions” were not metaphorical. They were drafty rooms and overcrowded classes at Robert Russa Moton High School in Farmville, Virginia; tar-paper shacks erected as overflow; students packed into a building designed for far fewer bodies than it held. They were the predictable result of a system that called itself “separate but equal,” and then refused to fund the “equal” part.

This week, the Capitol made that teenage question permanent, unveiling the statue of Barbara Rose Johns as Virginia’s new contribution to the National Statuary Hall Collection—replacing the former statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. The ceremony took place in Emancipation Hall and drew a bipartisan roster of Virginia officials and congressional leaders, and—most tellingly—hundreds of Johns’ relatives, a family gathering for a girl who never sought to be a symbol.

To understand why a teenager now stands where Lee once stood, you have to return to the spring of 1951, to a town with a courthouse square, a segregated school system, and a Black student who was about to make the grown-ups answer her.

The making of Barbara Rose Johns

Barbara Rose Johns was born in 1935 and grew up in a family that understood both work and movement—between places, between possibilities. Historians often point to an influence that was part kinship and part instruction: her uncle, Vernon Johns, a preacher known for refusing the softness that segregation demanded of Black people. In the family story, he asked children questions about Black history, and he did not accept shrugging as an answer.

But biography alone doesn’t explain what happened at Moton. Many teenagers are bright; few decide to reorganize the rules of their county.

Farmville and Prince Edward County sat inside a Virginia that had perfected the daily logistics of segregation: where Black schools were expected to make do, and where formal complaints were treated as disrespect. The “separate but equal” doctrine provided a legal wrapper around a plain reality: unequal budgets, unequal buildings, unequal political power.

At Moton High School, the inequalities were visible enough to shame even people invested in denying them. The school, built for a much smaller enrollment, was crowded; the county answered growth with temporary structures—“tar paper shacks”—that became a bitter shorthand for the Black school experience.

Parents petitioned. The all-white school board stalled. Students sat in the cold, or sweated, or shifted in rooms not meant to hold them.

Johns watched all of it and, according to accounts collected by Virginia historians, did something more ambitious than complain: she began to plan.

The strategy: not a tantrum, but a strike

It is often said—usually by those who benefit from order—that disruption is childish. That protest, especially when led by young people, is impulsive, emotional, unserious. Barbara Rose Johns understood this narrative instinctively, and she designed her action to defeat it.

What unfolded at Robert Russa Moton High School in the spring of 1951 was not a spontaneous outburst by frustrated students. It was, by every credible historical account, a carefully staged labor-style strike—planned over weeks, executed in minutes, and sustained by collective discipline.

Johns was sixteen, but she had already learned something many adults never do: that power rarely responds to polite requests, and that institutions reveal their priorities most clearly when routine is interrupted.

For years, Moton students and parents had followed the script prescribed to Black Virginians under Jim Crow. Complaints were filed. Petitions were submitted. Delegations appeared before the all-white school board. The response was delay masquerading as process. Enrollment grew; funding did not. Temporary buildings—tar-paper shacks—became semi-permanent fixtures. The message was clear: wait and be grateful for whatever arrives.

Johns chose a different script.

According to historians and contemporaries, she quietly assembled a small group of trusted classmates. Secrecy was essential—not only to avoid administrative interference, but because the consequences of open rebellion could extend far beyond school discipline. In a segregated county, retaliation could mean eviction, job loss, or violence directed at families. Planning a strike required not only courage, but discretion.

The students’ first strategic move was procedural: they requested a school assembly under the pretense of a visiting speaker. This was not mischief; it was an understanding of institutional choreography. Assemblies were one of the few moments when students could gather en masse without immediate suspicion.

When the day came—April 23, 1951—teachers were asked to leave the auditorium. That detail matters. Authority was not confronted directly; it was temporarily removed. In its absence, Johns took the stage.

Accounts describe her speech as controlled rather than incendiary. She did not beg. She did not shout. She asked questions, framed injustices, and then posed a choice. The conditions were intolerable, she argued—not because Black students lacked discipline or gratitude, but because the county had failed its obligations. And then she asked the question that would later be etched in stone: Were they going to accept it, or act?

More than 400 students walked out.

They did not scatter. They did not riot. They marched in formation, leaving campus and signaling that instruction could not continue without them. This, too, was strategic. A walkout is not symbolic protest; it is leverage. It creates absence where compliance is expected.

In many retellings, this moment is romanticized as youthful bravery. But what made it effective was that it resembled adult labor action more than adolescent rebellion. The students stayed out. They refused to return to class. They held their line.

The school board and local officials, accustomed to parental appeals they could ignore, suddenly faced a problem they could not administratively absorb: a school without students. The strike forced visibility. It transformed poor facilities from a background condition into a public crisis.

Crucially, Johns and her classmates did not frame their demand as an abstract moral appeal. They demanded a new school building. This initial framing mattered, because it exposed the hypocrisy of “separate but equal” on its own terms. If equality were truly the standard, then the county had already failed.

But the strike’s deeper significance lay in what followed—when adult civil rights lawyers recognized that the students’ action had created an opening not merely for reform, but for confrontation.

From facilities to constitution

When Johns and her classmates initiated the walkout, many were asking for what the county insisted was reasonable: equal facilities. But by the early 1950s, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and allied attorneys were narrowing in on a more radical premise: that segregation itself—no matter how “equalized”—was unconstitutional.

Prince Edward County did not initially look like the ideal terrain for a legal assault on Jim Crow. Yet the students’ determination, documented by Virginia historians, impressed attorneys Oliver W. Hill and Spottswood W. Robinson III when they came to Farmville. The lawyers offered a bargain that was also a warning: they would take the case if the community was prepared to challenge segregation, not merely demand a better segregated building.

Parents agreed—dozens of them. The lawsuit that emerged, Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, was filed in federal court in 1951 and became the only one of the cases consolidated into Brown v. Board of Education that was sparked by a student strike.

That detail matters: not just because it is unique, but because it clarifies who pushed history forward. The standard origin story of Brown centers adult plaintiffs, adult attorneys, adult judges. Moton adds a different engine: teenagers.

The legal journey was not immediate vindication. Early court decisions did what “separate but equal” was designed to do: acknowledge inequality while refusing to confront segregation as the underlying architecture. Yet the case moved upward, folding into a set of challenges that forced the Supreme Court to answer the question it had been dodging since Plessy: whether separation could ever be equal.

In 1954, Brown ruled that segregated public schools were unconstitutional.

In the nation’s most triumphal retellings, that is where the story ends: a decision, a moral arc, a before-and-after.

In Prince Edward County, it was where a different story began.

The backlash: when a county closed its schools

The Brown v. Board of Education decision is often remembered as a moral thunderclap—a moment when the nation awoke to the injustice of segregation and began, however haltingly, to correct it. In Prince Edward County, Virginia, the ruling landed differently. It was heard not as instruction, but as provocation.

If Barbara Rose Johns’ strike exposed the lie of “separate but equal,” the county’s response exposed something even starker: how far local power was willing to go to preserve segregation, even at the cost of public education itself.

Prince Edward County became the most extreme example of what came to be called Massive Resistance—a coordinated political strategy across Virginia to delay, dilute, or defy desegregation mandates. While some districts dragged their feet or tokenized integration, Prince Edward chose a more radical path.

It shut down its public schools.

From 1959 to 1964, the county closed its entire public school system rather than integrate it. White leaders framed the decision as fiscal necessity or constitutional disagreement. In practice, it was an act of racial triage.

White families were offered alternatives. Private “segregation academies” sprang up, subsidized indirectly through tuition grants and tax mechanisms. Churches, basements, and hastily organized classrooms filled the gap for some white students.

Black children, by contrast, were left with almost nothing.

Thousands of Black students—many of them the same generation inspired by the Moton strike—were denied formal education for years. Some families scraped together informal schooling. Others sent children to live with relatives in different counties or states. Many students simply lost critical years of learning, a deprivation that no court ruling could retroactively repair.

This was not an unintended consequence of resistance. It was the point.

The school closings revealed the central truth that Johns’ protest had anticipated: segregation was not about preserving community schools or local control. It was about maintaining hierarchy. When forced to choose between education and racial dominance, county leaders chose dominance.

For the Moton students and their families, the irony was devastating. Their lawsuit had helped dismantle the legal foundation of segregated schooling nationwide. In return, their own county withdrew education altogether.

The emotional toll of this period is difficult to quantify. Oral histories collected decades later describe confusion, anger, and betrayal. Children who had learned, through Johns’ example, that collective action mattered were suddenly punished not individually, but en masse. The lesson was brutal: even lawful resistance could be met with lawful cruelty.

Barbara Rose Johns herself was not spared the consequences. Fearing retaliation and threats, her family sent her away from Prince Edward County to complete her schooling. The architect of the strike was effectively exiled from the place she had tried to improve.

And yet, the county’s strategy ultimately failed.

Federal courts intervened. National attention intensified. By 1964—ten years after Brown, thirteen years after the Moton strike—Prince Edward County was forced to reopen its public schools.

By then, the damage was irreversible.

A generation had been marked by absence—by classrooms that never reopened, by lessons never taught, by futures narrowed. The cost of resistance was borne almost entirely by Black children, while the ideology that justified it collapsed under its own extremity.

This is the context that gives Barbara Rose Johns’ statue its sharpest edge.

She is not memorialized as a child who “won.” She is remembered as a child who told the truth early—about inequality, about power, and about the lengths institutions will go to avoid sharing either.

Her story insists on a harder reading of civil rights history: that progress is often followed by punishment, that victories invite backlash, and that courage does not guarantee protection.

Which is precisely why her presence in the Capitol matters—not as a comfort, but as a warning.

The personal cost: protection, exile, quiet

History loves to frame student activists as fearless, but fear is not the opposite of courage—it is often the condition for it.

After the strike and lawsuit, Johns’ family feared for her safety; historians note she was sent away for her senior year, to Montgomery, Alabama. That detail—exile for a child who had tried to improve her school—is a reminder that the price of leading is often paid in separation from home.

Johns attended Spelman College, then married, raised five children, and later worked as a librarian in the Philadelphia public school system. She lived, by many accounts, a relatively quiet adult life compared to the audacity of her teenage act.

In the AP coverage of the statue unveiling, one of her daughters, Terry Harrison, described her mother in terms that resist monument-making: “brave, bold, determined,” yes, but also “warm and loving.” It is the kind of portrait family members often offer: a refusal to let the public version swallow the private one.

Johns died in 1991, at 56.

A statue cannot restore the years she spent living with the consequences of a moment the country has only recently learned to name.

The students behind the headline: a movement made of many

Even as the Barbara Johns story has become more widely told, it can still tilt too heavily toward singular genius—one girl, one speech, one walkout.

But the strike held because hundreds of students chose to walk out with her. The lawsuit moved forward because parents agreed to be plaintiffs—historians cite 74 parents representing 118 students in the Virginia case.

And the legal argument that reached the Supreme Court was made possible not only by famous names, but by local resolve: families who risked jobs, credit, standing, safety.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture’s documentation of the Moton case emphasizes that NAACP attorneys pushed the strategy beyond facilities toward desegregation—an escalation that required buy-in from students and parents who understood they were not simply asking for nicer classrooms, but challenging the rules of their entire county.

If Johns was the spark, the community was the oxygen.

Why her statue, and why now

The announcement was never just about art. It was, from the beginning, about substitution—about which Virginians deserve to represent Virginia beneath the dome.

Robert E. Lee’s statue in the Capitol was removed in 2020, amid a national reevaluation of Confederate iconography. Virginia’s choice of replacement—Barbara Rose Johns—was a statement with multiple layers: replacing a Confederate general with a Black teenage schoolgirl; trading a mythology of “Lost Cause” honor for a record of democratic dissent; moving the center of gravity from battlefield leadership to classroom struggle.

The new statue was sculpted by Steven Weitzman and depicts Johns beside a lectern, holding a tattered book overhead. The book matters: it is both a literal object and a symbol of what the fight was for. Education was not, for these students, an abstract “issue.” It was a daily deprivation and a future foreclosed.

At the unveiling ceremony, according to AP and the Washington Post, officials emphasized Johns’ role as a civil rights trailblazer, and the event drew significant family presence—more than 200 relatives, in AP’s account.

Yet there is an unavoidable tension in such ceremonies: monuments can congratulate a country for change that is incomplete. Even The Post noted the stubborn persistence of segregation in American schooling, citing research that underscores how many schools remain intensely segregated.

If Johns’ statue were merely an endpoint—proof that the nation has “moved on”—it would betray her. Her question, engraved in stone, is the opposite of closure.

The expanded history: Moton, Brown, and the long argument over “equal”

To treat Barbara Rose Johns as simply “a precursor to Brown” is to miss what makes the Moton strike such a revealing episode in the American story.

Brown is often taught as a moral awakening handed down by the Supreme Court. In reality, it was the product of many local conflicts, each exposing the lie of “separate but equal” in its own vernacular. In Farmville, the lie was visible in architecture: the mismatch between Farmville High School for white students and Moton for Black students, between durable construction and temporary shacks, between what the county funded and what it neglected.

Johns’ strike turned the physical facts of inequality into a political crisis that the county could not ignore. That is the first important shift: a student protest that made conditions public and urgent.

The second shift came when NAACP attorneys persuaded families to widen their demand from “equal facilities” to “no segregation.” This was not a semantic move; it was a strategic escalation that risked provoking harsher retaliation.

The third shift is the one the nation memorializes: the case joins others and becomes part of Brown.

But Farmville’s true lesson is what came after: the slow grind of compliance, the political invention of “Massive Resistance,” and the willingness of local leaders—especially in Prince Edward County—to sabotage public education rather than integrate it.

In other words: Barbara Rose Johns did not simply help win a legal decision. She helped expose how American democracy behaves when a subordinate group demands equal access to the state’s most basic promise. The state—at first—tries to ignore. Then it tries to bargain. Then it tries to punish. And only then, under sustained pressure, does it begin to change.

This is why a statue of Johns is not simply a “civil rights tribute.” It is a reminder that children have often been forced into political adulthood by the failures of adult governance.

The human scale: what a strike feels like from the inside

Most accounts of the Moton walkout include details that suggest Johns understood something sophisticated about power: you do not merely criticize it; you interrupt it.

A school’s power is routine. Bells. Attendance. Compliance. The strike broke the routine and created a different kind of classroom—one in which students taught the county what it had tried to teach them: that some people were meant to accept what they were given.

There is also the quiet intimacy of the planning: a small group of students carrying a secret, testing loyalties, deciding who could be trusted. Historians have described Johns as having selected a handful of classmates and worked for months.

And there is the emotional intensity of the moment she took the stage: a teenager in front of hundreds, with adults temporarily removed from the room, asking her peers to risk punishment.

It is easy, in retrospect, to treat the walkout as inevitable. It wasn’t. If students hesitated, the plan could have collapsed. If parents refused to become plaintiffs, the legal strategy would have had no vessel. If the county had responded with both repression and a rapid upgrade, the case might have remained limited to facilities.

Instead, the community persisted, and the conflict grew into something that reached the highest court in the land.

The statue as editorial choice

National Statuary Hall is often described as a museum of state pride. But it also functions as an editorial page carved in stone: each state chooses what it wishes to say about itself.

Virginia’s choice to replace Lee with Johns is therefore not only a moral statement; it is a narrative decision. It proposes a different through-line for the Commonwealth: not simply founding fathers and battlefield leaders, but Black girls and public schools; not the romance of rebellion in defense of slavery, but rebellion in defense of equal citizenship.

This is also why the statue is designed the way it is. Johns is shown not in passive remembrance but in action—speaking, holding a book aloft, near a lectern. The sculpture insists that her power was not granted; it was performed.

What her story asks of the present

A monument can be a way of outsourcing conscience: put the right figure in the right building, and feel the ledger balance.

Barbara Rose Johns’ legacy does not cooperate with that impulse.

Her question is deliberately unfinished. “Are we going to just accept these conditions…?” is an invitation to look around—at schools, at funding formulas, at zoning, at the persistence of racial separation by policy and by market, and at the way “equal opportunity” is still often a slogan applied unevenly.

The Washington Post’s coverage of the statue unveiling underlines this discomfort: the symbolism is profound, but the conditions that made Johns necessary have not vanished; segregation persists in new forms.

In that sense, the statue is best understood not as a capstone but as a prompt.

A teenager has been placed in the Capitol. Not because the nation has finished the work she started—but because it hasn’t.

And because it needs, still, to be asked—by someone too young to have benefitted from cynicism—what it plans to do about the conditions it keeps reproducing.