KOLUMN Magazine

Where Black Art Lives, Again

The Studio Museum returns to Harlem with a new building, an expanded vision, and a renewed commitment to the community that has always shaped it.

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a bright November morning in 2025, the line on West 125th Street did not feel like a queue so much as a gathering. It moved slowly, almost ceremonially, past storefronts and bus stops and the everyday choreography of Harlem’s most storied thoroughfare. Parents held children by the hand. Elders leaned on canes and memories. Artists—some emerging, some long established—stood quietly, surveying the street as if they were waiting not simply to enter a building, but to reenter a chapter of their own lives.

After seven years, the Studio Museum in Harlem was open again.

The reopening marked the end of a long and carefully sustained absence. Since closing its doors in 2018 to make way for redevelopment, the Studio Museum had never quite been gone. It traveled—into pop-up exhibitions, partner institutions, classrooms, digital platforms, and the studios of artists whose careers it continued to shape. But for Harlem, the return of the museum to 125th Street carried a particular gravity. This was not merely the reopening of a cultural institution. It was a homecoming.

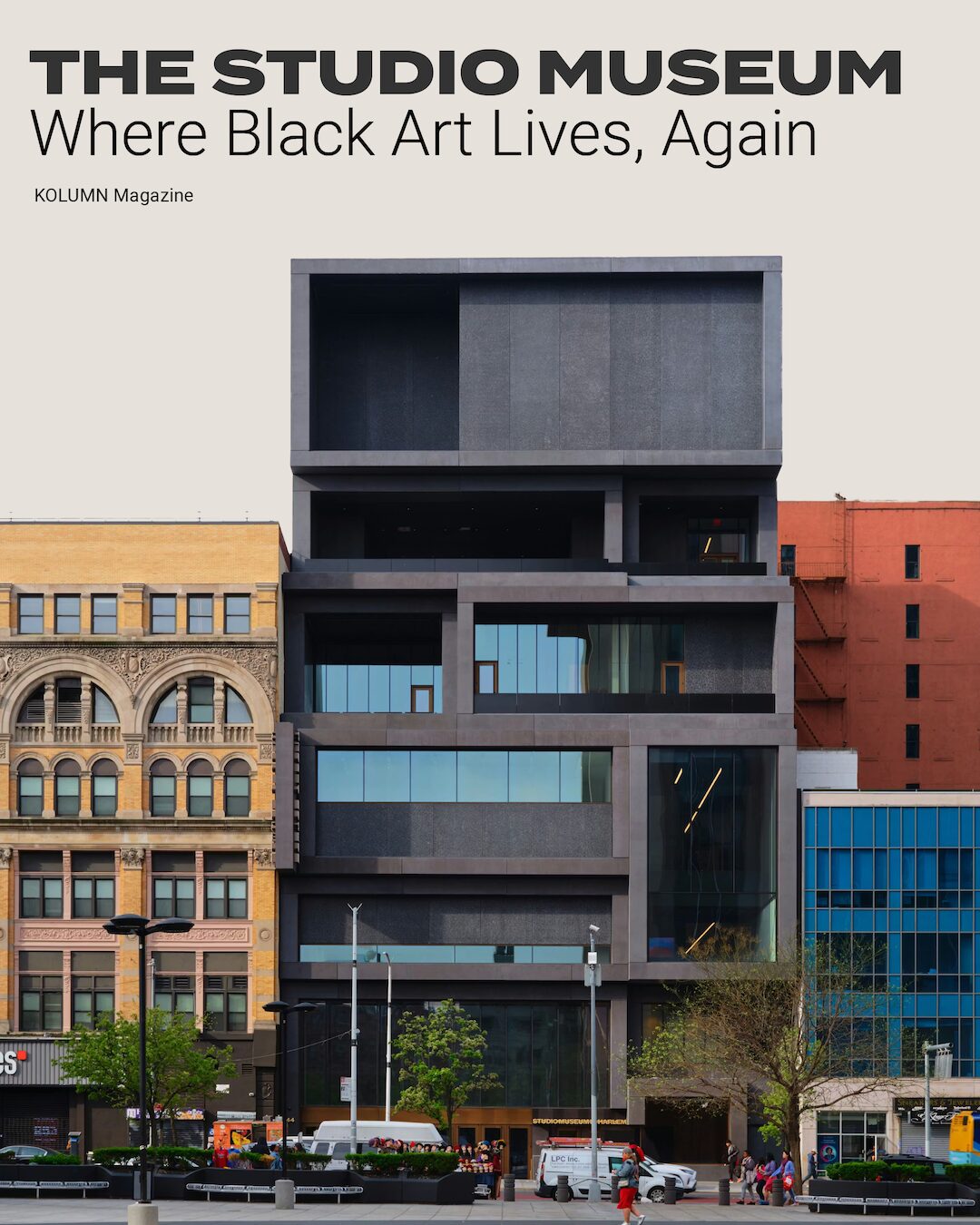

The new building—seven stories, 82,000 square feet, purpose-built for the first time in the museum’s history—rose from the footprint of the museum’s former home like an affirmation made physical. Expanded galleries, education studios, archival space, and a rooftop garden announced an institution thinking not only about display, but about time: how art is made, how it is studied, how it is passed on.

The museum’s leadership framed the reopening simply and deliberately: Where Black Art Lives. It was less a slogan than a statement of record. For nearly sixty years, the Studio Museum has been a place where artists of African descent have not only been exhibited, but believed in—where experimentation was protected, careers were incubated, and Black art was treated as neither exception nor trend, but as the core of the American story.

A museum born of insistence

The Studio Museum in Harlem was founded in 1968, a year that now reads like a hinge in American history. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated that spring. Cities were burning, grieving, demanding to be heard. The art world, meanwhile, remained largely insulated from the country’s upheavals—its major institutions slow to recognize that Black artists were not emerging voices but long-standing ones, already shaping modernism, abstraction, figuration, performance, and conceptual practice, often without institutional acknowledgment.

Harlem, for its part, had always known this. For decades, it had been a proving ground for Black cultural thought: the Harlem Renaissance had announced that Black art could define an era; postwar Harlem had sustained a vibrant ecosystem of writers, musicians, visual artists, and political thinkers even as redlining, disinvestment, and urban renewal hollowed out much of the neighborhood’s material infrastructure. What was missing was not talent or vision, but an institution willing to insist—publicly, permanently—that Black art belonged at the center of American cultural life.

The Studio Museum was created to be that insistence.

It was founded by a coalition of artists, community leaders, and philanthropists who understood that representation alone was insufficient. The goal was not merely to hang Black artists on museum walls, but to build an institution structured around their presence—one that would support experimentation, scholarship, and professional development with the same seriousness afforded to white artists in established museums downtown.

From the beginning, the museum rejected narrow definitions. “Black art” was not treated as a genre or a sociological category, but as a vast and evolving field—one that encompassed abstraction as readily as figuration, conceptualism as readily as narrative, politics as readily as pleasure. The museum’s early exhibitions made clear that artists of African descent were not responding belatedly to modernism; they were actively shaping it.

Crucially, the museum embedded artists into its daily life. The Artists in Residence program, launched in the institution’s earliest years, transformed the museum into a site of production rather than mere presentation. Artists were given space, time, stipends, and—perhaps most importantly—visibility. Visitors could see work being made, ideas being tested, failures unfolding alongside breakthroughs. The museum was not presenting a finished story; it was hosting a living one.

This model proved radical in its quiet way. Over time, artists who passed through the residency program would go on to international acclaim, their early years marked by the kind of institutional belief that is difficult to quantify but impossible to replace. The Studio Museum became known not only for identifying talent, but for sustaining it—offering a counterweight to an art market that often rewards speed over depth.

Equally important was the museum’s relationship to Harlem itself. Unlike institutions that arrived in the neighborhood as symbols of redevelopment or cultural tourism, the Studio Museum grew alongside its community. Its education programs served generations of Harlem children. Its galleries were spaces where residents encountered their own histories reflected with dignity and complexity. Admission policies, public programs, and community partnerships reinforced the idea that this was not a museum about Harlem, but a museum of Harlem.

By the 1980s and 1990s, the Studio Museum’s influence extended far beyond its modest physical footprint. Curators trained there carried its philosophies into major museums across the country. Scholars cited its exhibitions as foundational texts. Artists credited it as a place where their work was first taken seriously—not as an exception, but as part of a continuum.

And yet, even as its stature grew, the museum retained a kind of productive humility. It remained responsive rather than declarative, curious rather than conclusive. Its exhibitions often posed questions rather than answers, trusting audiences to engage critically. This intellectual generosity became one of its hallmarks.

To call the Studio Museum a response to exclusion is accurate, but incomplete. It was also an act of imagination—a refusal to accept the limits imposed by existing institutions, and a belief that something better could be built, even in the face of structural inequity. Its founding was not a protest alone, but a proposition: that Black artists deserved an institution equal to their ambition, complexity, and contribution.

That proposition has never expired.

The reopening of the Studio Museum in 2025 does not mark a departure from this origin story. It marks its continuation, scaled to meet a new moment. The building may be larger, the resources more substantial, the audience broader—but the underlying insistence remains the same. Black art belongs. Black artists deserve space. And Harlem is not merely a backdrop for that truth, but one of its primary authors.

In that sense, the museum was never waiting to be reborn. It was always becoming—guided, still, by the conviction that culture does not ask for permission. It insists.

The meaning of the wait

When the museum closed its doors in 2018, the decision was framed as an investment in the future. The existing building—originally constructed as a bank branch—had served the institution well, but it could no longer support the scope of its programming or the growth of its collection. A new building promised expanded galleries, improved accessibility, and space commensurate with the museum’s role as a national cultural anchor.

Still, the absence was felt. For seven years, the familiar rhythm of exhibitions, studio visits, and community programs had to find new forms. The museum responded by refusing to retreat. It staged exhibitions throughout the city, maintained its artist residency program, and deepened partnerships with other institutions. Harlem was never abandoned, even without a fixed address.

By the time the reopening date was announced, the sense of anticipation had accumulated layers. The wait had coincided with a pandemic that reshaped public life, with renewed national conversations about race and representation, and with ongoing changes in Harlem itself. The return of the Studio Museum felt, for many, like a stabilizing moment—a reminder that some institutions endure not by standing still, but by adapting without surrendering their purpose.

A building designed for belonging

The new Studio Museum does not announce itself with spectacle. Instead, it engages the street with a sense of invitation. The façade, composed of warm concrete panels, reflects the light differently throughout the day, echoing the changing rhythms of 125th Street. Large windows allow passersby to glimpse interior activity, blurring the line between museum and neighborhood.

Inside, the building unfolds with a logic that privileges movement and gathering. Galleries are flexible rather than prescriptive. Education spaces are generous and visible. Circulation areas feel less like corridors and more like places to pause, observe, and converse. The design emphasizes continuity between floors, reinforcing the idea that learning, making, and exhibiting are interconnected acts.

At the top of the building, a rooftop garden offers a different kind of gallery. Designed as both landscape and gathering space, it draws on Harlem’s ecological and diasporic histories, incorporating plantings that reflect migration, resilience, and care. From this vantage point, visitors can see the neighborhood spread out below—church spires, apartment buildings, traffic, and sky—situating the museum not above Harlem, but within it.

The building’s scale allows the museum to do what it has always done, only more fully. It can now present multiple exhibitions simultaneously, host larger educational programs, and provide artists with resources that were previously constrained by space. The architecture serves the mission rather than the reverse.

Opening with history, looking forward

The museum’s opening exhibitions were carefully chosen to reflect continuity rather than rupture. At the center of the inaugural season was a major presentation devoted to Tom Lloyd, the artist whose work anchored the Studio Museum’s very first exhibition in 1968. Lloyd’s pioneering engagement with light, technology, and abstraction offered a reminder that Black artistic innovation has always extended beyond narrow categories or expectations.

Alongside the Lloyd exhibition, From the Studio: Fifty-Eight Years of Artists in Residence traced the legacy of the museum’s residency program, which has supported hundreds of artists over the decades. The exhibition functioned as both retrospective and reaffirmation: a visual record of how sustained institutional belief can shape artistic possibility.

These exhibitions did not attempt to summarize Black art. Instead, they demonstrated a principle the museum has long upheld: that Black art is not a genre, but a constellation of practices, ideas, and lineages. By foregrounding process, experimentation, and intergenerational dialogue, the museum signaled its intention to remain a living institution rather than a mausoleum.

A public institution in the fullest sense

On reopening weekend, admission was free. Families streamed in alongside scholars, collectors, tourists, and longtime supporters. Children sprawled on the floor during workshops. Elders lingered in galleries, reading wall texts carefully. Conversations spilled into stairwells and elevators.

This accessibility was not incidental. From its founding, the Studio Museum has understood itself as a public institution in the fullest sense—not merely open to the public, but accountable to it. Education has never been an auxiliary program; it has been central to the museum’s identity. The new building expands that capacity with dedicated classrooms, maker spaces, and multipurpose rooms designed to host everything from lectures to community meetings.

Financially, the reopening reflected years of careful planning and broad-based support. The museum’s capital campaign, which raised more than $300 million, drew contributions from individuals, foundations, corporations, and public agencies. This coalition of support underscored the institution’s unique position: rooted in Harlem, yet recognized nationally as indispensable.

Corporate sponsorships helped underwrite opening programs, while public funding ensured that accessibility remained a priority. The museum’s leadership has consistently emphasized transparency and balance—leveraging resources to expand opportunity without compromising mission.

Harlem, held with care

The return of the Studio Museum comes at a moment when Harlem continues to navigate change. New developments rise alongside historic brownstones. Longtime residents share streets with newcomers drawn by the neighborhood’s cultural resonance. In this context, institutions carry added responsibility.

The Studio Museum has long understood that responsibility not as a burden, but as a calling. It hires locally. It collaborates with neighborhood organizations. It programs with Harlem in mind—not as an audience to be courted, but as a community to be served.

For many residents, the museum’s reopening represents continuity amid transformation. The building may be new, but the values are familiar: seriousness, generosity, and a belief that art matters because people matter.

The museum’s presence on 125th Street remains symbolic. The site once housed a bank—a place where people came to protect what they had. Today, it houses an institution devoted to protecting something less tangible but no less vital: cultural memory, creative labor, and the right to imagine freely.

The threshold, crossed again

By the afternoon of reopening day, the line had thinned, but the energy remained. Visitors moved through the building with a mix of curiosity and recognition. For first-time guests, the museum offered discovery. For longtime supporters, it offered reassurance.

The most telling moments were small ones: a child pointing at a painting and asking questions; an artist pausing quietly in front of a work by someone who had once been an artist-in-residence; a neighbor greeting a security guard by name.

Museums often speak of legacy. The Studio Museum speaks, instead, of care—care for artists, for audiences, for histories that have too often been overlooked. The reopening did not feel like a conclusion. It felt like a continuation, strengthened by time and intention.

As the doors closed that evening and reopened the next morning, the museum resumed its most important work: being there. On 125th Street. In Harlem. Where Black art lives—not temporarily, not conditionally, but with permanence and pride.