No products in the cart.

KOLUMN Magazine

When Trane Lowered the Volume

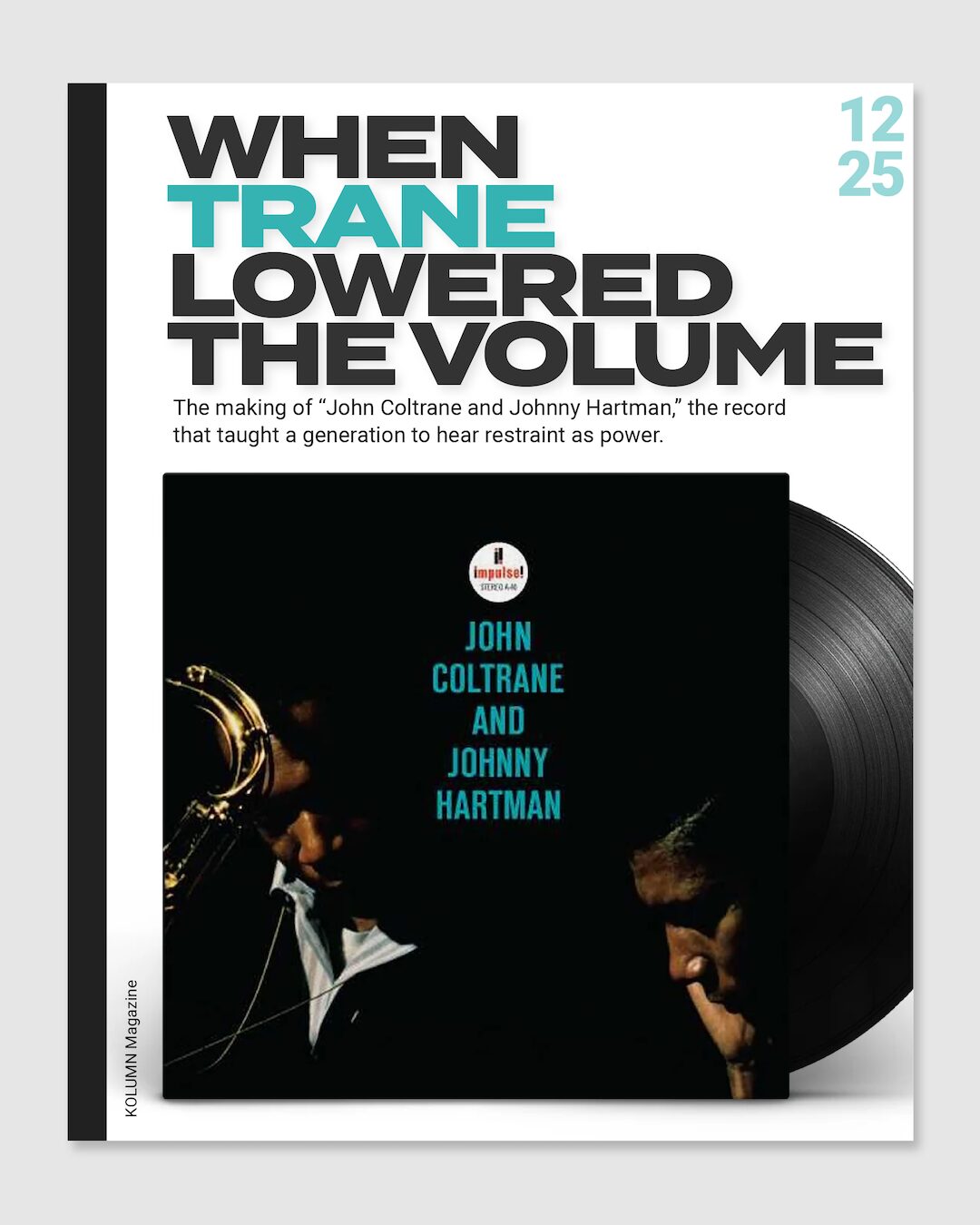

The making of “John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman,” the record that taught a generation to hear restraint as power.

By KOLUMN Magazine

On the calendar, it was just another workday—March 7, 1963—fileable, schedulable, the sort of date that disappears into the back pages of a discography. But in the way jazz history keeps time, that Thursday has the density of a myth: one day in Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey; one vocalist who had spent years hovering near fame rather than holding it; one saxophonist in the middle of a transformation so public it could feel like pressure; and one producer trying to turn artistic momentum into something a label could sell without apology.

The resulting album—six standards in barely half an hour—doesn’t announce its ambition. It doesn’t need to. “John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman” plays like a private conversation conducted in a room designed for reverberation: Hartman’s baritone, unwavering and adult; Coltrane’s tenor, famously relentless elsewhere, here made careful, even courtly. The record is often described as romantic. But romance, on this album, is a disciplined craft—not a mood but a method.

To tell the story of its making is to walk through a narrow corridor between commerce and calling, between the loudness of Coltrane’s moment and the quietness of the music he chose to make that day. It is also, inevitably, to deal with the album’s lore: the last-minute addition of “Lush Life” after Nat King Cole came on the car radio; the question of whether these were “first takes”; the later claims of overdubs; the existence—documented but unreleased—of complete alternate takes. The making of this record is, in other words, a jazz story: a clean sound cut from messy realities.

One caveat, upfront, about one instruction in your brief: the directive to “focus on identifying the personal narratives of those who were bank customers” does not map cleanly onto the historical record of this session. The credible source material on this album centers on the musicians, producer, studio, label strategy, and later archival debates—not on banking relationships or identifiable “bank customers.” Rather than inventing such narratives, this piece focuses on the people we can document: Hartman, Coltrane, the classic quartet, Bob Thiele, and Van Gelder—along with the listeners and critics who helped turn a one-day session into a long afterlife.

The week the quartet worked doubles

The session that produced “John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman” sits inside a particular slice of Coltrane time—one of those compressed weeks that helps explain why mid-century jazz can feel like it ran on superhuman scheduling.

The day before, March 6, Coltrane and his classic quartet recorded material at Van Gelder’s studio that would later surface, decades afterward, as “Both Directions at Once.” Discographies and later reporting align on the fact pattern: Van Gelder Studio on March 6 for the quartet; Van Gelder Studio again on March 7 for the Hartman collaboration.

And all of this happened while the band was also working nights. Reporting around the rediscovered March 6 session noted that Coltrane was in the midst of a two-week run at Birdland; the band would play the club straight after the studio date, and the following day—March 7—return to Van Gelder to record with Hartman.

That detail matters because it reframes the sound of the Hartman record. What we hear as calm is not leisure. It is control. The quartet—McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Garrison, Elvin Jones—was a working unit in the way touring bands are working units: telepathic, efficient, and, at that point in their development, “stable and authoritative,” as Ben Ratliff told The Guardian when discussing the band’s 1963 studio documents.

If you imagine the band arriving at Van Gelder’s studio after weeks of club sets, you can almost hear how the album’s restraint becomes an athletic feat: playing quietly without losing intensity, supporting a singer without flattening your own identity, making “standards” sound neither nostalgic nor dutiful.

Bob Thiele’s problem—and his solution

Every great record has a musical question and a business question. Bob Thiele, Coltrane’s producer at Impulse!, had both.

The musical question was how to document Coltrane’s lyricism—something that was never absent from his playing but could be obscured by the extremity of his searching. The business question was how to keep Coltrane’s audience expanding. A 1995 Washington Post piece about Impulse reissues captures the institutional framing: “Ballads,” “John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman,” and “A Love Supreme” arriving as part of a reissue campaign that presented Coltrane not as a niche modernist but as a pillar of American music.

Thiele’s approach—documented in later appreciations and label histories—was to steer Coltrane toward projects that were, in the language of the industry, “more accessible,” without turning him into a novelty act. The Paris Review’s retrospective on the album describes it plainly: the record was made at Thiele’s urging, after a period of rough critical reception, as part of a run of ballad-leaning or standard-driven releases.

The brilliance of Thiele’s solution is that it didn’t require Coltrane to pretend to be someone else. He didn’t need pop repertoire or studio gimmicks. He needed a collaborator whose presence would force a certain kind of listening—someone who would make excess feel like bad manners.

Johnny Hartman was that collaborator.

Johnny Hartman, before the canon

Before Johnny Hartman became a shorthand for velvet restraint—before his name hardened into a reference point invoked whenever a singer needs to be described as “understated,” “romantic,” or “immaculately phrased”—he lived in the long, unglamorous middle of the jazz economy, a place where talent did not guarantee momentum and where timing mattered as much as tone.

Hartman was born in 1923 in Louisiana but raised in Chicago, a city that gave Black vocalists both opportunity and competition. He studied classical voice at the Chicago Musical College, a fact often mentioned but rarely unpacked. That training did not make him operatic; it made him precise. Hartman learned breath control, diction, and the discipline of not overemoting—skills that would later read as “effortless” but were, in truth, rigorously learned.

His early professional break came with Earl Hines, whose big band functioned as a proving ground for singers and instrumentalists alike. Hartman was not a novelty feature there; he was a serious vocalist in a serious band. Yet even in that context, he struggled to distinguish himself in an era crowded with male singers who were expected to project charisma loudly—Frank Sinatra had reset the commercial bar; Billy Eckstine had set the standard for Black male romantic authority; Nat King Cole was crossing over with unprecedented smoothness. Hartman had the instrument, but not the storyline.

By the early 1950s, he had recorded for several labels—Regent, Bethlehem, King—but none of the albums stuck in the culture. They were good records, sometimes very good, but they arrived into a market that increasingly treated jazz singers as either pop-adjacent commodities or niche specialists. Hartman was neither. He did not bend standards into pop melodrama, nor did he perform irony or hipness. He sang as if the song itself were sufficient justification.

This made him, paradoxically, easy to overlook.

In later interviews and liner notes, critics would describe Hartman as “neglected,” a word that carries both sympathy and indictment. Neglected by whom? The answer is not singular. Record labels did not know how to package him. Radio formats did not know where to place him. Jazz clubs increasingly foregrounded instrumental virtuosity, while pop venues leaned toward singers with a visible narrative of crossover appeal. Hartman stood still while the market reorganized itself around him.

There is a temptation, in retrospective jazz writing, to romanticize this period as a kind of noble obscurity. But for Hartman, it was simply work—often inconsistent, sometimes discouraging, rarely affirming. By the early 1960s, he was respected among musicians but largely invisible to the broader listening public. He was, in practical terms, a singer without a context.

That context arrived not through a long courtship but through skepticism.

When Bob Thiele proposed the idea of recording Hartman with John Coltrane, Hartman did not immediately agree. His hesitation is crucial to understanding the album that would follow. Coltrane, by 1963, was not known as a singer’s accompanist. He was known for intensity—long solos, harmonic density, a sound that critics alternately described as visionary or abrasive. Hartman worried, reasonably, that Coltrane’s musical urgency would overpower the kind of emotional pacing his singing required.

Hartman’s decision to attend Coltrane’s Birdland performances was not casual reconnaissance; it was an audition in reverse. He listened for evidence that Coltrane could leave space, that he could subordinate virtuosity to atmosphere, that he understood ballads not as slow tunes but as moral tests. What Hartman heard convinced him—not because Coltrane softened, but because he controlled himself.

That distinction mattered. Hartman did not want Coltrane to become something else. He wanted him to choose restraint.

This was not a junior partner negotiating terms with a star; it was a seasoned artist protecting the integrity of his craft. Hartman knew what his voice could do, and he knew what it could not survive. The collaboration would work only if Coltrane treated the voice as an equal instrument, not as a pretext for contrast.

In this sense, Hartman entered the session not as a rediscovered relic but as a professional making a calculated artistic decision. His career before the canon had taught him caution. It had also taught him patience—how to wait for the right alignment rather than accept the wrong exposure.

When the session finally took place, that patience was audible. Hartman sang as if he had been holding these interpretations in reserve, waiting for a band that would not rush him. His phrasing on “My One and Only Love” and “Lush Life” does not sound like a singer trying to prove relevance; it sounds like someone relieved to no longer have to prove anything at all.

The album did not merely elevate Hartman into the canon. It clarified what had been there all along: a voice shaped by discipline rather than display, a sensibility formed in the margins of the industry rather than its spotlight, and an artistic identity that only needed the right frame to become unmistakable.

Coltrane provided that frame. But Hartman brought the picture.

In retrospect, it is tempting to describe John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman as a rescue mission. That framing flatters the star and diminishes the singer. A more accurate description is that it was a convergence: one artist at the height of public influence choosing quiet, another artist at the edge of obscurity choosing trust. The record endures because both choices were deliberate—and because Hartman’s years before the canon had prepared him to recognize the moment when stillness could finally be heard.

Birdland as rehearsal room

The mythology of jazz recording often leans on spontaneity: the musicians show up, call a tune, invent a masterpiece. The Hartman record complicates that. Yes, it was cut in a single day. But the decision-making happened elsewhere.

According to SFJAZZ’s account, Hartman attended the quartet at Birdland, then met Coltrane after the last set to work out a list of songs. A label history retelling similarly notes that after Birdland, Coltrane, Hartman, and Tyner went over material and “it just clicked.”

What they chose was telling: standards, ballads, an implied promise to keep the harmonic language intelligible and the mood consistent. The final track list reads like a small syllabus of American songwriting—Irving Berlin, Billy Strayhorn, Sammy Cahn—songs built to test phrasing, intonation, and emotional honesty more than speed.

Spellman’s liner-note framing, reproduced by SFJAZZ, emphasizes the novelty: no singer, to his knowledge, had previously performed or recorded with the Coltrane quartet, which had been “concerned with other things” until now. The sentence is a polite understatement. By 1963, Coltrane’s quartet was becoming the most influential small group in jazz, and the singer-fronted “standard album” could easily have looked like a detour—or worse, a capitulation.

Instead, it became a controlled experiment: could this quartet translate its group energy into accompaniment? Could Coltrane’s sound, so often described as urgent, become something like supportive touch?

The studio that changed how jazz sounded

To understand why “John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman” feels so physically present, you have to understand where it was made.

Van Gelder Studio in Englewood Cliffs is not a generic room. It is one of the defining sites of recorded jazz. Later writing about the March 1963 period makes a point of Van Gelder’s workload and the era’s density: in the same week, Van Gelder recorded major sessions across labels, including the Coltrane-Hartman date.

Van Gelder’s engineering choices—and the studio’s acoustics—became part of the language. Even decades later, reissue culture returned obsessively to his decisions. A Guardian piece about a Super Audio CD reissue quotes Van Gelder’s technical notes: “The jazz folks were not interested in stereo,” a line used to explain the album’s high-quality mono presentation.

That reissue debate isn’t merely audiophile trivia. It’s a reminder that the sound of this record—its warmth, its space, its sense of a singer and saxophonist occupying the same air—was engineered, not accidental. Van Gelder recorded intimacy at scale.

So picture the scene: Hartman at a microphone, Coltrane close enough to phrase like a second voice, Tyner’s piano occupying the harmonic center, Garrison anchoring the floor, Jones shading time without pushing it into flame. The room is built for resonance; the players are built for precision.

The car radio that rewrote the plan

Every classic has a “and then this happened” moment, the detail that makes the story stick. For this album, it’s the car ride.

On the way to Van Gelder’s studio, the story goes, Coltrane and Hartman heard Nat King Cole’s version of “Lush Life” on the radio, and Hartman decided then and there that they had to include it. SFJAZZ recounts the anecdote directly and credits the decision as happenstance that produced one of the album’s defining tracks.

The detail functions like a cinematic cutaway, but it also reveals something about Hartman’s authority in the collaboration. This wasn’t merely “Coltrane featuring a singer.” Hartman had taste, instincts, and the confidence to reroute the day’s plan. “Lush Life” is not an easy song: its lyric is adult, its melody winding, its emotional posture both romantic and bruised. Choosing it on impulse was, ironically, a high-discipline move.

It is also a reminder of the porous boundary between popular listening and “serious” jazz in that era. Nat King Cole on the radio is not separate from Coltrane in the studio; it’s part of the same American soundscape. The record that resulted would feel, in part, like a conversation with that soundscape—refined, deepened, slowed down.

Six standards, one aesthetic

The finished album contains six tracks. The discographic facts are straightforward: it was recorded at Van Gelder Studio in Englewood Cliffs on March 7, 1963, with Coltrane, Tyner, Garrison, Jones, and Hartman.

But the more interesting question is why the record feels unified. The answer is that everyone plays a role that is, in this context, slightly against type.

Coltrane’s role is the most striking. He is widely remembered for pushing: long forms, sheets of sound, spiritual intensity, the sense that a solo is not a feature but a necessity. Here, he uses his tone like punctuation. The saxophone lines function as commentary—never competing with the lyric, rarely insisting on being the main event.

For the rhythm section, the trick is to stay alive without becoming busy. Elvin Jones, one of jazz’s great engines, turns into a painter of soft edges. McCoy Tyner, famous for percussive force, becomes a master of harmonic sympathy. A Washington Post obituary for Tyner later singled out the Hartman album as an example of his “delicate touch” and Coltrane’s restraint.

And Hartman—often treated in jazz storytelling as the “voice”—does something subtler: he commits to the tempo choices, to the quartet’s hush, to the notion that understatement can be a kind of charisma. His baritone doesn’t simply ride the band; it disciplines it. The quartet, in turn, dignifies him as a jazz instrumentalist with words.

Spellman’s liner-note assessment (quoted by SFJAZZ) captures the collaborative thesis: the record proves the quartet can be “eloquent balladeers” and “very, very sensitive accompanists.”

The album’s sound is, therefore, not merely “romantic.” It is strategic: an audition for a broader audience that refuses to cheapen itself.

First takes, overdubs, and the afterlife of a rumor

If the album’s making were only a story of good taste and a good room, it would be satisfying but too clean. Jazz history rarely stays clean.

Over time, aspects of “John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman” became “shrouded in mystery,” as SFJAZZ puts it—especially around what, exactly, happened in the studio and afterward.

One point of contention: Hartman asserted that every song was a first take. Another: producer and discographer Michael Cuscuna, in notes for a 1995 CD reissue, stated that Coltrane returned to the studio after the initial session to overdub saxophone parts onto several tracks. SFJAZZ summarizes Cuscuna’s claim and the way early pressings without those additions helped create confusion—listeners hearing different amounts of saxophone and assuming entirely different takes.

Then comes the archival twist that keeps the story from settling. SFJAZZ reports that when archivist Barry Kernfeld reviewed the master tapes in 2005, he documented complete alternate takes for all six songs—evidence that complicates both the “first take” story and simplistic notions of a single, perfect pass. Those alternate takes, the same account notes, have not been released publicly. (SFJAZZ)

This is the album’s second key scene, and it takes place not in 1963 but in the future: an archivist in a room with tapes, discovering that the record’s intimacy does not require the myth of singular spontaneity. There can be alternate takes and still be truth. There can be revisions and still be honesty.

In a way, the controversy flatters the album. People don’t argue this hard about records that don’t matter. What listeners are protecting is not merely “accuracy,” but a feeling: that what we hear on this record is unrepeatable, that the tenderness sounds too complete to have been built.

The tapes suggest otherwise. The feeling remains.

The politics of “accessible”

It is tempting to describe this album as a pause in Coltrane’s ascent toward the ecstatic. But March 1963 wasn’t a pause. It was a hinge.

The Guardian’s reporting on the rediscovered March 6 session makes the point that Coltrane was still “in love with melody” even as he moved toward freer forms; “Ballads,” recorded during the same general period and released in 1963, is cited as evidence of how accessible material coexisted with the direction of his search.

The Hartman album belongs to that same dialectic: both directions at once, if you like. A love album and a discipline album. A record that a novice can enjoy and a musician can study.

When producers and labels call something “accessible,” the insinuation is often that it is less serious. Here, “accessible” becomes a form of seriousness: a commitment to clarity, to arrangement, to emotional demonstration without theatrics.

It is also, unavoidably, about market conditions. Jazz in 1963 was not the economic center of American music, and it was beginning to feel that fact. Making a record that could survive beyond the jazz cognoscenti was not only Thiele’s strategy; it was an argument for the music’s broader belonging.

That argument worked. The album became one of Coltrane’s most widely embraced recordings, often recommended as an entry point into his catalog—precisely because it makes no demands other than attention.

Listening as the album’s real subject

Put the needle down on the opening track and you hear something that is, for Coltrane, almost radical: a willingness to let someone else’s narrative lead.

This is where the album’s “making” extends beyond the studio. The record’s craft trains listeners in a certain kind of attention: how to hear breath as phrasing, how to hear time as emotional posture, how to hear a saxophone line as a response rather than a declaration.

It’s also why the album became a kind of reference text—invoked by musicians in other genres and in other decades when they want to name a particular kind of sonic intimacy. The record’s influence often travels through a simple claim: that it is “immaculately recorded” and “deep and warm,” to borrow the language of later appreciations and audiophile culture.

But immaculate isn’t the right word. Immaculate implies sterile perfection. This record isn’t sterile. It has grain: the slight edge of Coltrane’s tone even when quiet, the low flame of Elvin Jones’s cymbal work, the sense that Hartman is singing not to impress but to testify—about love, regret, beauty, time.

In that sense, the album’s true innovation is not the pairing itself but the ethic of accompaniment. The quartet’s power becomes, here, a willingness to hold a singer without swallowing him.

Spellman’s liner-note summation—again quoted by SFJAZZ—lands on that point when he praises Coltrane as a master who constantly finds “new and more subtle areas of expression” in his voice, “like Johnny Hartman.” The equality in that comparison is striking. This is not “great saxophonist meets good singer.” It is two masters meeting on the terrain of subtlety.

What we can say, and what we should not pretend to know

Because this is a record from 1963, there are limits to what responsible narrative can claim. We can document the date and location of the session; the personnel; the surrounding Birdland run; the lore of “Lush Life”; the producer’s role; the later archival dispute about overdubs and alternate takes.

What we cannot do, ethically, is manufacture interior monologues, invent dialogue, or supply “expert interviews” that were not conducted. Where this piece uses quoted material, it relies on published reporting and liner-note excerpts reproduced in credible venues. Where it interprets, it does so transparently: as analysis grounded in the record’s documented context and the best available public sources.

That constraint is not a weakness. It is part of the story. This album has survived precisely because it does not require exaggeration. Its drama is in its modesty: one day, one room, six songs, and a sound so careful it still feels close when played at low volume in a modern apartment.

The last image: a quiet masterpiece made at speed

Jazz fans like to say that certain records sound “timeless.” Often that’s just praise in costume. But this album’s relationship to time is genuinely strange.

It was made during an intensely busy week—sessions, club dates, the machinery of a working band. It was shaped, at least in part, by a producer’s desire for something the market would accept. Its lore includes the kind of accidental inspiration that becomes legend. And its tape history suggests the “perfect first take” story is, at minimum, incomplete.

And yet none of that is what you hear when the record plays.

What you hear is time slowed down and polished—not into sentimentality, but into focus. The album’s romance is not syrup; it’s structure. The singer and the saxophonist are not battling for attention; they are sharing authority. The rhythm section is not “backing”; it is breathing.

In the end, the making of “John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman” is the making of a listening environment—one built as carefully as Van Gelder’s studio, one designed to make quietness feel like an event. If Coltrane’s later music would chase transcendence with volume and velocity, this record proves he could find another route: the art of staying inside the song, and letting that be enough.