Before Fashion Looked to Africa, Africa Tailored Itself

La SAPE’s century-old system of elegance predates the global runway.

By KOLUMN Magazine

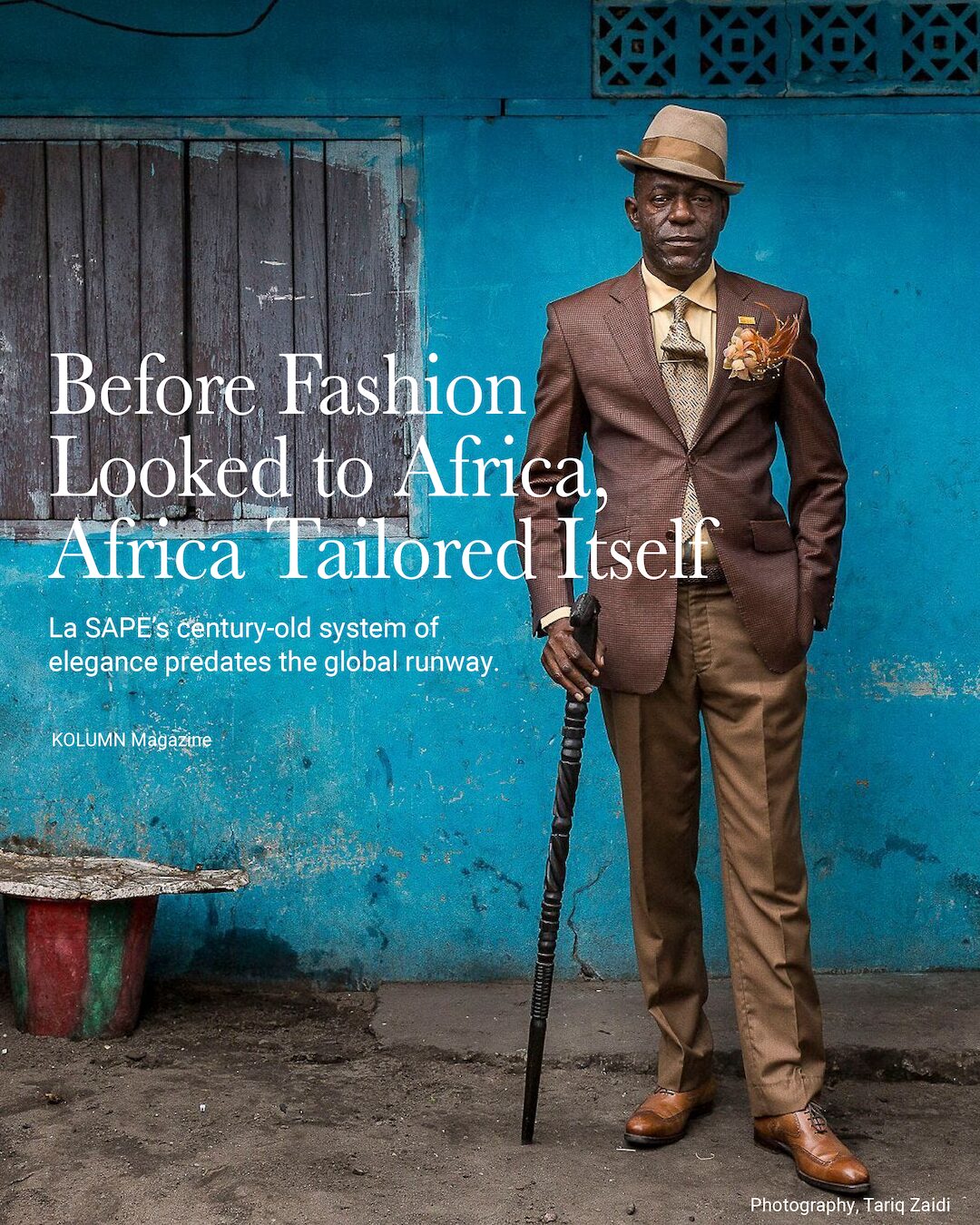

In Bacongo—Brazzaville’s neighborhood of narrow streets and loud afternoons—style arrives before the person. A flash of lemon-yellow sock. A jacket with shoulders as sharp as a thesis. A cane used less for balance than for punctuation. The movement has choreography: a half-turn to catch the light, a palm over the lapel to show the lining, a pause that dares the onlooker to admit what they came to see.

To outsiders, La SAPE can look like an aesthetic contradiction—high fashion in low-income streets, luxury labels against corrugated metal. The misread is common and revealing: that elegance must be purchased, that it must be quiet, that it must be sanctioned by the people who already have power. La SAPE rejects all three. Even its name—Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes, “Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People”—frames dress as a social function, not a private indulgence.

To be a sapeur is to accept a premise that the fashion industry often markets but rarely interrogates: clothes can change your life. Not because they magically raise your income or protect you from the state, but because they alter how you are read—by your neighbors, by the police, by employers, by the mirror. In that sense, the sapeur is not a consumer; he is an author. And La SAPE is less a trend than a cultural system—rules, rituals, status hierarchies, moral codes—built over a century of colonialism, independence, dictatorship, migration, and economic whiplash.

What follows is the history of that system: how it started, what it meant, how it survived, and why fashion—especially menswear—still borrows from it, often without naming the debt.

Origins: colonial Brazzaville and the joke inside the imitation

Brazzaville in the 1920s was a city built to be looked at from above. French colonial planners divided it with deliberate clarity: the European quarters, orderly and well-serviced, and the African neighborhoods, crowded and policed, expected to supply labor but not ambition. Dress codes were implicit but unmistakable. Clothing marked who commanded and who complied, who spoke and who was spoken to.

And yet it was precisely within this rigid visual order that La SAPE began to take shape—not as admiration, but as interpretation.

Congolese men employed as domestic workers, clerks, porters, and drivers encountered European clothing daily, often at intimate proximity. They laundered suits, polished shoes, brushed hats. They learned the grammar of tailoring the way one learns a second language: through repetition, correction, proximity to power. Over time, they began to wear versions of what they handled—sometimes through cast-offs, sometimes through local tailors reproducing silhouettes from memory, sometimes through garments acquired at great personal cost. What looked, from the colonial perspective, like mimicry was something else entirely.

It was parody with discipline.

Scholars and cultural historians who track La SAPE’s early years emphasize this distinction. The imitation was not naïve. It was knowing. It exaggerated formality in spaces where colonizers expected deference, not elegance. It took garments meant to signify authority and wore them in contexts where that authority frayed—on dusty streets, in dance halls, in informal gatherings where Congolese men controlled the audience. The joke was subtle but sharp: if refinement was the colonizer’s claim to legitimacy, then refinement could be performed without the colonizer.

In this sense, early sapologie operated like visual satire. The suit became a mask that revealed rather than concealed. A perfectly pressed jacket worn by someone barred from political participation exposed the absurdity of colonial hierarchies more effectively than any pamphlet. The wearer was saying, without speaking: If this is what civilization looks like, then I have mastered it. What, then, is your excuse?

This inversion mattered because colonial ideology depended on visible difference. The suit disrupted that economy. It suggested equivalence—or worse, superiority—in a language the colonizer could not easily dismiss. The fact that these early sapeur practices unfolded among men with limited economic power only sharpened the point. Elegance, in this context, was not proof of assimilation. It was evidence of authorship.

Crucially, La SAPE did not emerge as an individual quirk or isolated affectation. It grew as a shared code, a way of reading and recognizing one another. Certain neighborhoods in Brazzaville—Bacongo most famously—became laboratories of style where reputations were built not on wealth alone but on coherence: the harmony of color, the balance of proportion, the confidence of carriage. To dress well was to demonstrate self-command in a system designed to deny it.

That is why La SAPE survives the charge of being “European fashion transplanted to Africa.” From the beginning, it was African modernity articulated through borrowed materials. The suit was not the message. The message was the mastery—and the refusal embedded inside it.

André Matsoua and the “uniform” as political theater

If La SAPE has a foundational myth, it is not about a garment but about a refusal.

André Matsoua, a Congolese figure whose life straddled colonial service and anticolonial resistance, occupies an outsized place in the movement’s historical imagination. In many tellings, he appears less as a tailor than as a provocateur: a man who understood that clothing could operate as a public argument.

Matsoua served in the French military during World War I, a fact that placed him inside the machinery of empire even as it exposed him to its contradictions. When he returned to Brazzaville in the 1920s, he brought with him not only uniforms and European attire but also a sharpened awareness of how power was staged. According to accounts preserved in Congolese oral history and later cultural writing, Matsoua refused to remove his uniform in civilian contexts—wearing it insistently, sometimes defiantly, long after protocol demanded otherwise.

This act was not vanity. It was theater.

In colonial society, uniforms functioned as visual contracts. They marked authority, loyalty, and place. To wear one improperly—or too long—was to scramble the script. Matsoua’s persistence transformed the uniform from a symbol of obedience into a symbol of unresolved claim. If he had worn France’s insignia in war, what, exactly, did France owe him in peace? Respect? Rights? Recognition? The uniform asked the question every time he appeared in public.

Within the emerging logic of La SAPE, this gesture reverberated. Matsoua modeled a principle that would become central to sapologie: clothing could be used to hold power accountable to its own symbols. The suit, like the uniform, was not neutral. It was a promise someone had made—and often broken.

As Matsoua’s political activism intensified—he would later be imprisoned and die in detention—his image took on a near-messianic quality among followers. In some interpretations, he becomes less an originator of style than an originator of method. He demonstrated that dress could be a nonverbal manifesto, that visibility itself could be mobilized against domination.

This matters because it distinguishes La SAPE from fashion-as-escape narratives. The sapeur does not disappear into fantasy. He appears, deliberately, in public. He insists on being seen, evaluated, discussed. The elegance is confrontational precisely because it refuses the expected posture of grievance or submission.

Matsoua’s legacy also helps explain why La SAPE would later clash so directly with post-independence authoritarianism. When Mobutu Sese Seko attempted to regulate dress through the abacost, he was not merely proposing a new aesthetic. He was attempting to reclaim symbolic control. For sapeurs shaped by a tradition that treated clothing as political speech, that control was unacceptable. The suit had already been established as a site of dissent.

In this way, André Matsoua’s sartorial defiance becomes a through-line rather than a footnote. From colonial uniforms worn too long, to European suits worn where they were discouraged, to contemporary sapeurs parading luxury in spaces marked by deprivation, the logic remains consistent: dress is a claim, and refusing to dress “appropriately” is sometimes the most appropriate response.

La SAPE’s origins are often photographed in color—bold jackets, polished shoes—but its earliest chapters are written in tension. Matsoua understood something that later sapeurs would refine into art: when power controls language, the body becomes text. And when the body is text, clothing becomes grammar.

The évolués and the suit as proof of modernity

By the 1940s, the movement’s aesthetics overlap with the évolués—the French colonial category for educated, urban Africans who were encouraged to adopt European manners and dress as evidence of “civilization.” In practice, this was a trap: assimilation offered conditional status while reinforcing the idea that dignity was something Europe dispensed. La SAPE navigated that contradiction. As Africa Is a Country notes, the évolués embraced sapeur fashion, embedding it into anticolonial critiques.

This phase matters because it clarifies La SAPE’s double function:

Respectability (presenting oneself as disciplined, modern, “proper”)

Rebellion (using that presentation to expose the violence of a system that required it)

From the outside, those can look like opposites. In the sapeur logic, they often coexist.

Independence, dictatorship, and the abacost: why the suit became contraband

The story of La SAPE cannot be separated from post-independence state power—especially in what was then Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) under Mobutu Sese Seko. Mobutu’s “Authenticité” campaign promoted African cultural nationalism, including restrictions on Western dress and the promotion of the abacost—a Mao-style jacket whose very name is commonly glossed as “down with the suit.”

In this period, the suit stops being merely aspirational. It becomes defiant.

Multiple accounts connect sapologie (the philosophy of La SAPE) to resisting Mobutu-era dress codes. A scholarly paper on fashion, mobility, and protest notes Papa Wemba’s role in defying imposed dress norms while elevating European-style couture as central to sapeur culture. Cultural writing likewise describes sapologie “exploding” in response to Mobutu’s policies that discouraged suits and ties.

This is the moment when La SAPE’s stakes sharpen. Wearing the “wrong” jacket is no longer a matter of taste; it is a claim about freedom—about the right to choose one’s symbols.

Papa Wemba: the pop star who turned style into a mass movement

If the 1920s give La SAPE an origin story, the 1960s onward give it scale. Here, no figure looms larger than Papa Wemba, a Congolese musician frequently described as a key promoter—sometimes “the pope”—of La SAPE.

Wemba’s importance is structural. Music made sapologie portable: the look could be learned in bars and bedrooms, in taped performances and album-cover fantasies, not only in elite circles. He also fused the sapeur ethos with celebrity—proving that elegance could be a form of mass identification, not aristocratic separation.

French newspaper coverage after his death explicitly links the popularization of La SAPE to the 1960s, while tracing its deeper origins back to the 1920s and framing the movement as a response to colonial legacy and later repression (including Mobutu-era diktats).

Fashion historians sometimes treat musicians as style mannequins for designers. In La SAPE, the dynamic is reversed: musicians become evangelists for a street philosophy of dress, and designers become one of the movement’s raw materials.

The diaspora engine: Paris, Brussels, and the economics of return

La SAPE is also a migration story. Movement between the Congos and Europe—especially France and Belgium—helped create a feedback loop: clothes acquired abroad, status performed at home, reputations built on the ability to move between worlds. The sapeur’s walk often carries that history: a person performing cosmopolitanism in a place that colonialism tried to provincialize.

This is also where La SAPE’s most debated feature becomes unavoidable: cost. The stereotype paints the sapeur as irresponsible—someone buying luxury while living precariously. But that framing flattens what the movement actually does. It treats dress as frivolity rather than as social capital, artistry, and sometimes survival. NPR’s well-known 2013 feature introduces the subculture through that tension—“in a poor city… a singular purpose: to look rich,” then complicates it into a more precise aim: to look good, to embody suave elegance.

From within the movement, spending is often framed as sacrifice for meaning—what others might call excess, the sapeur calls investment in identity. That doesn’t absolve the economic risk; it explains why the risk is taken.

Women sapeuses: “looking smart” and re-writing the rules

For years, Western imagery of La SAPE centered men. That was never the whole story. Women have long participated, and their participation is not simply additive—it challenges the movement’s gender assumptions.

The Guardian’s reporting on sapeuses quotes women describing their joy in extravagance and the desire “to look smart,” highlighting a lineage that includes prominent elders in the community. The existence of women sapeurs clarifies something central: La SAPE is not merely about menswear. It is about tailored authority—who gets to wear it, and what it does when they do.

In practice, women sapeuses also expose a wider truth about dandy culture globally: tailoring has always been a gender argument. The sapeuse makes that argument explicit with every lapel.

Civil conflict, hardship, and the insistence on beauty

In the 1990s and 2000s, the Congos experienced periods of severe political instability and violence. La SAPE did not disappear. In some accounts, it sharpened—turning even more toward performance in the face of collapse.

Artists and documentarians who have lived close to the movement often emphasize this context without reducing sapeurs to spectacle. A Leica blog interview with Congolese photographer Baudouin Mouanda stresses his intent to show sapeurs’ lives and moods in the streets, avoiding staged posing and insisting on an Africa “on the move.” Another interview, connected to the 1-54 art platform, places his focus on sapeurs against the backdrop of civil unrest, framing the movement’s cultural role inside pressure.

These perspectives matter because they resist the easy, exoticizing takeaway—“Look at these colorful suits!”—and return us to what sapeurs themselves often argue: elegance is not denial. It is method.

The rules: why La SAPE is not just “wearing a suit”

To understand La SAPE historically, you have to treat it like a system with governance.

Most descriptions emphasize not only clothes but also manners: restraint, posture, verbal wit, the ability to animate a street corner into an event. The acronym itself elevates “ambiance-making.” Sapeurs cultivate a code that distinguishes them from mere label-chasing. The suit is necessary but not sufficient; the performance completes it.

This is where the movement’s influence on fashion becomes clearest. Contemporary menswear often sells “effortless” style. La SAPE demonstrates that effortlessness is crafted—hours of planning, saving, pressing, rehearsing. Luxury houses have always depended on that kind of devotion. Sapeurs simply make the devotion visible.

The fashion industry’s debt, and its temptation

The global fashion industry has long mined Black and African style as a source of energy while often treating its origins as a mood rather than a history. La SAPE complicates that extraction in two ways:

It is already a fashion system.

It has tastemakers, critics, status structures, and aesthetic debates. It is not raw material waiting to be “elevated.”

It is a political archive.

From colonial satire to Mobutu-era defiance, the suit in this context carries meanings brands cannot ethically strip away without telling a lie.

French coverage of the movement has explicitly warned about the risk of La SAPE’s “commercial aestheticization” by Western brands and media, noting concerns that spectacle can drain the tradition of its original force even as artists and photographers argue for more respectful representation.

La SAPE now: the future of the suit, written on the street

In the end, La SAPE’s history is a century-long refusal of a single story. It is not merely “imitation of Europe.” It is not merely “escapism.” It is not merely “consumerism.” It is a cultural technology built by people negotiating the brutal economics of visibility.

A sapeur in Brazzaville, dressed in a suit whose seams carry both aspiration and irony, walks like someone who has made a decision: if the world insists on reading him, he will supply the text. He will not be rendered as a statistic, a stereotype, a cautionary tale. He will be rendered—meticulously—as himself.

And that is why the fashion industry keeps circling back. La SAPE understands something fashion sometimes forgets: elegance is not the opposite of struggle. In certain places, it is one of the most sophisticated languages struggle ever invented.