KOLUMN Magazine

Ailey’s

America

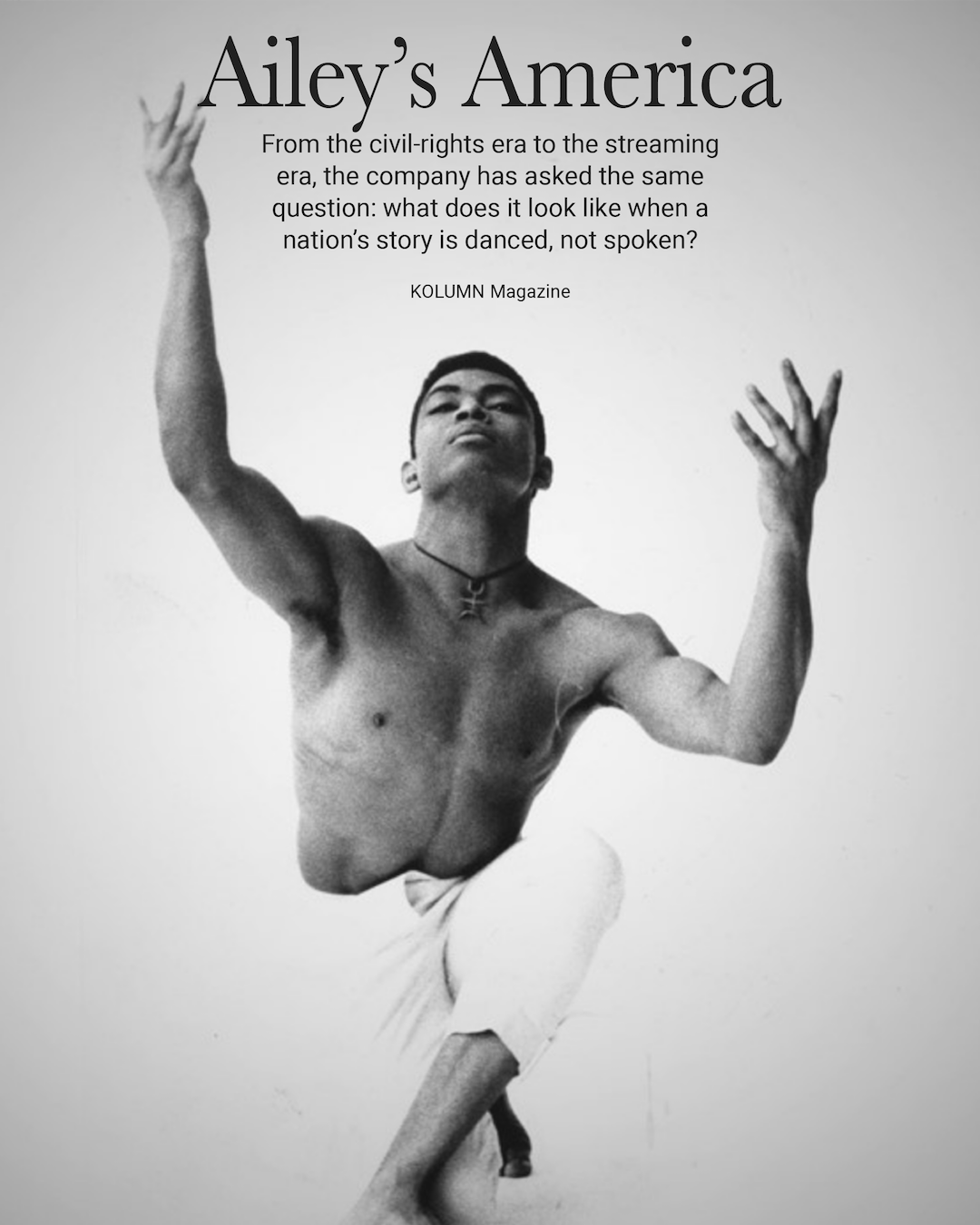

From the civil-rights era to the streaming era, the company has asked the same question: what does it look like when a nation’s story is danced, not spoken?

By KOLUMN Magazine

In New York, there are certain December rituals that function less as entertainment than as civic weather: the tree, the windows, the slow crush of tourists in Midtown. And then there is the Alvin Ailey season—often at City Center—where people arrive with the peculiar confidence of those who can name the ending before the first note. They are not there to be surprised. They are there to be reassured that something beloved still exists, still holds.

When the curtain rises on Revelations, the audience can feel the piece like a memory before it becomes an image: bodies angled into supplication, arms carving the air in arcs that seem to lift and lower a whole history at once. Ailey’s signature work, performed to spirituals and gospel-rooted music, is described by the company as an exploration of “deepest grief and holiest joy.” It is also, in a way few works manage, a portable homeland: the kind of dance that can travel the world and still feel unmistakably American.

Robert Battle—who grew up in Miami and later became the company’s artistic director—has described Revelations not as a relic but as craft. “It’s so brilliantly crafted,” he told The Washington Post, noting the way it speaks both to Black history and to audiences abroad.

That duality—specific and universal, personal and public—is the company’s founding riddle. Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater did not become a global institution because it diluted its origins. It grew because it insisted that Black cultural inheritance was not a sidebar to American life, but one of its central engines.

On Ailey’s own repertory page, the choreographer is quoted describing African American cultural heritage as one of America’s “richest treasures”—“sometimes sorrowful, sometimes jubilant, but always hopeful.” In a phrase, he outlined the company’s business model before anyone called it that: do not translate the source material into something more palatable. Trust that the source material already contains the country.

1958: a beginning that sounded like a dare

The origin story, as histories often do, begins with a room.

In March 1958, Ailey and a group of young Black modern dancers premiered their first performance at the 92nd Street Y in New York. The scale was modest—nothing like the institutional machinery the organization now represents: multiple companies, a major school, community programs, a home base, and a touring footprint that makes it one of the most visible dance brands in the United States.

But even then, Ailey was building an argument: that Black dancers and Black stories belonged at the center of modern dance, not at its edges. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture later framed the breakthrough plainly: in 1960, he “mesmerized the dance world” with Revelations.

The timing mattered. The civil-rights movement was not a backdrop; it was the atmosphere. Ailey’s company toured extensively as the country argued over who counted as fully American, and the ensemble’s presence—Black bodies claiming space on concert stages—became its own kind of rebuttal.

Ailey was not inventing Black dance from scratch; he was curating a lineage and insisting on its legitimacy. The work drew on multiple vocabularies—modern, jazz, ballet, African diasporic forms—and turned hybridity into a signature rather than a compromise.

“Blood memories”: the rural church inside the proscenium

Revelations is the company’s most famous work, but it is also its clearest thesis statement: the stage can hold the Black church and not diminish it.

The Ailey organization describes the ballet as born out of Ailey’s “blood memories” of childhood in rural Texas and the Baptist church. PBS, in a collection of Ailey quotations, reinforces the same idea—Ailey locating the work in memory and embodiment.

That insistence on memory as source is one reason the piece endures. It does not treat spirituality as decorative texture. It treats it as a structure—something you live inside, something that shapes how you stand, how you bend, how you recover.

Ailey’s genius was not merely choreographic. It was editorial. He chose images that carried multiple truths at once: suffering and humor, fatigue and praise, longing and defiance. The choreography is accessible without being simplistic—one of the most difficult balances in concert dance, which can confuse obscurity with depth.

And because it is accessible, it became an emblem, sometimes to the company’s frustration. Revelations is not the whole story; it is the best-known chapter. The larger history of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater is a history of resisting the trap of being known for only one work—while also honoring the work that built the house.

The dancers who watched history happen—and only later realized it

The Guardian, in an oral-history-style piece about Revelations, captured something rare: dancers describing the first time they felt the ground shift.

Sylvia Waters, a former Ailey dancer who saw the first performance of Revelations in 1960, recalled how it landed before it had acquired its myth. She described it as “deeply soulful,” and noted that “at the time you are part of history you never realise it.”

That line—about not realizing you are in history while you are in it—is an honest description of how institutions are made. They are not built by people who think, daily, “I am building an institution.” They are built by people trying to get through rehearsal, trying to get through touring, trying to get through the month.

The company’s own archive-like storytelling underscores how quickly the organization began to move through the world: grants, major performances, national recognition, and appearances at the White House during the late 1960s, documented in the Ailey timeline.

Ailey wasn’t merely making dances. He was building infrastructure—touring routes, donor relationships, institutional credibility—so that Black dance could be not just seen but sustained.

Judith Jamison: a star enters, a successor is chosen

Judith Jamison did not enter the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater quietly. She arrived in 1965—tall, striking, physically commanding—at a moment when modern dance still trafficked in narrow ideas of who could be a leading woman on a concert stage. Jamison’s body alone disrupted those assumptions. She was not willowy in the way the field often preferred; she was expansive, architectural, unmistakably present. Alvin Ailey saw not a problem to be solved, but a future to be shaped.

“I didn’t know what he saw,” Jamison later reflected in interviews over the years, including with The New York Times and The Guardian. What Ailey saw, repeatedly, was scale: emotional scale, physical scale, symbolic scale. Jamison could carry weight—narrative, spiritual, political—without collapsing under it.

That faith culminated in Cry (1971), a solo Ailey created for Jamison as a birthday gift to his mother. The piece unfolds in three movements, tracing the arc of Black womanhood through labor, loss, endurance, and exaltation. Jamison performs it not as a character study but as a vessel—absorbing grief and releasing it, again and again. Over time, Cry became inseparable from her image, and from the company’s broader commitment to centering Black women’s interior lives onstage. Reuters later described the work as one of the most iconic solos in modern dance history, and Jamison as its definitive interpreter.

Yet Jamison’s significance to Ailey did not end with her star power. When Ailey died in 1989, after years of illness that were only partially understood by the public at the time, the company stood at a crossroads. AIDS was devastating the dance world. Funding was precarious. The question was not simply who would lead next, but whether the institution itself could survive without its founder’s singular force of personality.

Ailey had already answered that question, quietly, in advance. He named Jamison artistic director, entrusting her with both the repertory and the philosophy behind it. It was an act of continuity rather than preservation. Jamison did not approach the role as a guardian frozen in reverence; she approached it as a builder.

Under her leadership, which lasted more than two decades, the company expanded its repertory well beyond Ailey’s own choreography, commissioning and staging works by artists who pushed the vocabulary of modern dance while remaining in dialogue with its roots. She strengthened the school, deepened international touring, and—crucially—helped professionalize the institution at a moment when arts organizations led by Black founders were often expected to survive on charisma alone.

In interviews with the Associated Press and The Washington Post, Jamison spoke candidly about the burden of succession: honoring Ailey’s vision without turning him into a monument. She resisted what she once called “the museum trap,” insisting that Ailey’s work had to remain alive, responsive, and technically exacting—or it would lose its moral authority.

That insistence led to one of the company’s most consequential milestones: the opening of the Joan Weill Center for Dance in 2005. The building, a permanent home in Manhattan, signaled something rare in American cultural life—a Black-led dance institution claiming not just visibility, but infrastructure. Jamison framed the achievement not as arrival, but as responsibility: a place where dancers could train, rehearse, and imagine futures longer than a single contract.

Former dancers and colleagues have described Jamison’s directorship as both demanding and maternal—a combination that reflected her own artistic lineage. She was exacting about musicality and line, unsparing about discipline, but deeply invested in the humanity of the people onstage. “She expected you to know why you were dancing,” one former company member told The Guardian. “Not just how.”

By the time Jamison stepped down in 2011, she had done something few successors manage: she made herself indispensable, then made herself replaceable. The company she handed off was financially stable, internationally respected, and artistically plural—capable of surviving leadership change without losing its center of gravity.

Her legacy inside Ailey is therefore double-edged in the best sense. She is remembered as the woman who embodied Ailey’s vision with almost mythic force—and as the executive artist who ensured that vision could outlive both of them. In the lineage of the company, Jamison is not simply the second chapter. She is the hinge: the figure who turned a founder’s dream into an enduring institution, and proved that succession, when chosen with intention, can be an act of love rather than loss.

Ailey’s paradox: belonging everywhere without losing itself

Part of what made Ailey a phenomenon is that the company traveled well—across regions, across countries, across languages. Battle’s comment about foreign audiences being “enrapture[d]” by Revelations points to the company’s export power.

But exportability carries risk: the risk of being treated as a single, consumable symbol of Blackness—a cultural product that audiences can applaud without engaging the politics that birthed it.

The best Ailey programming has often resisted that flattening by expanding the repertoire. The company staged work by choreographers who widened modern dance’s possibilities and insisted that “Ailey” could be a platform, not a museum label.

In one Ailey blog post about Black choreographers who contributed to the repertory, George Faison—who danced with the company in the late 1960s—described seeing Ailey perform as a student and feeling his own life reroute. “I can’t even imagine what I wanted to do before that,” he said.

That is one of the company’s quieter legacies: not only the audiences it moved, but the artists it activated. Ailey did not simply build a troupe; it helped build a pipeline.

The third generation: Robert Battle and the question of evolution

When Robert Battle took over as artistic director in 2011 (after Jamison’s tenure), he inherited a rare burden: leading an institution that is already iconic, already expected to deliver a particular feeling on demand.

His public commentary often frames the company as a bridge between eras. In the Washington Post, his assessment of Revelations as craft rather than nostalgia reads like strategy: preserve the masterpiece by treating it as living technique.

Battle also represented a wider shift in how audiences encounter dance—through video excerpts, through viral moments, through a culture that often meets choreography in thirty-second doses. The Ailey brand adapted without abandoning the long-form reality of the art: touring programs, education initiatives, deep repertory.

In practical terms, that meant the company had to remain a high-performing enterprise, not just a cultural symbol. It also meant speaking to a country in which public funding for the arts is unstable and philanthropy is shaped by fashion.

Ailey’s survival has depended on something less poetic than “inspiration”: governance, fundraising, and the kind of institutional discipline that mirrors the physical discipline onstage. The Ailey timeline reads, in places, like a story of arts administration as much as choreography—grants, major honors, milestones, rebrands.

A new era: Alicia Graf Mack and the inheritance of a living archive

The organization’s own history page notes that Alicia Graf Mack—former Ailey dancer and a leader in dance education—has been named the fourth artistic director of AILEY.

A recent People feature on a milestone season underscores what that transition represents: the company continuing to honor its founder’s vision while “ushering in a new era,” with Graf Mack citing the influence of her mentor Judith Jamison.

The succession matters because it signals what institutions often struggle to do: evolve without severing the cord to their origin story. Ailey’s origin story is not merely branding; it is an artistic premise about whose experiences are worthy of concert stages.

That premise, in 1958, was radical.

In 2025, it is still contested—because the cultural mainstream often embraces Black expression most readily when it is packaged as heritage rather than as contemporary critique. Ailey has had to negotiate that tension for decades: honoring tradition, commissioning the new, refusing to be trapped in a single narrative.

What the company is really selling

The easiest way to summarize the history of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater is to list milestones: 1958 founding, 1960 Revelations, Jamison’s rise, the post-1989 institutionalization, the building opening in 2005, the later leadership transitions.

But that version misses what audiences recognize viscerally the moment Revelations begins.

Ailey’s deeper product is permission: permission for Black memory to occupy the center of an American stage without apology, and permission for audiences—Black, Brown, white, immigrant, local—to find themselves in those memories without claiming ownership of them.

It is also, as Ailey himself framed it, an inheritance that carries sorrow and jubilation together, insisting both are American.

Sylvia Waters’ recollection—history happening before you can remember to name it—captures the company’s accidental genius. The dancers made work to survive the present moment; the work survived them; the work became a ritual for strangers; the ritual became an institution.

And every season, as the audience leans forward at the same familiar musical cues, the company reenacts the founding logic: the archive is not in a museum case. It is in the body—disciplined, sweating, listening—turning “blood memories” into motion again.