KOLUMN Magazine

A Village

Under One

Roof

Inside Minneapolis’ indoor “tiny house” experiment —and the uneasy questions it raises about safety, dignity, and what counts as a way home.

By KOLUMN Magazine

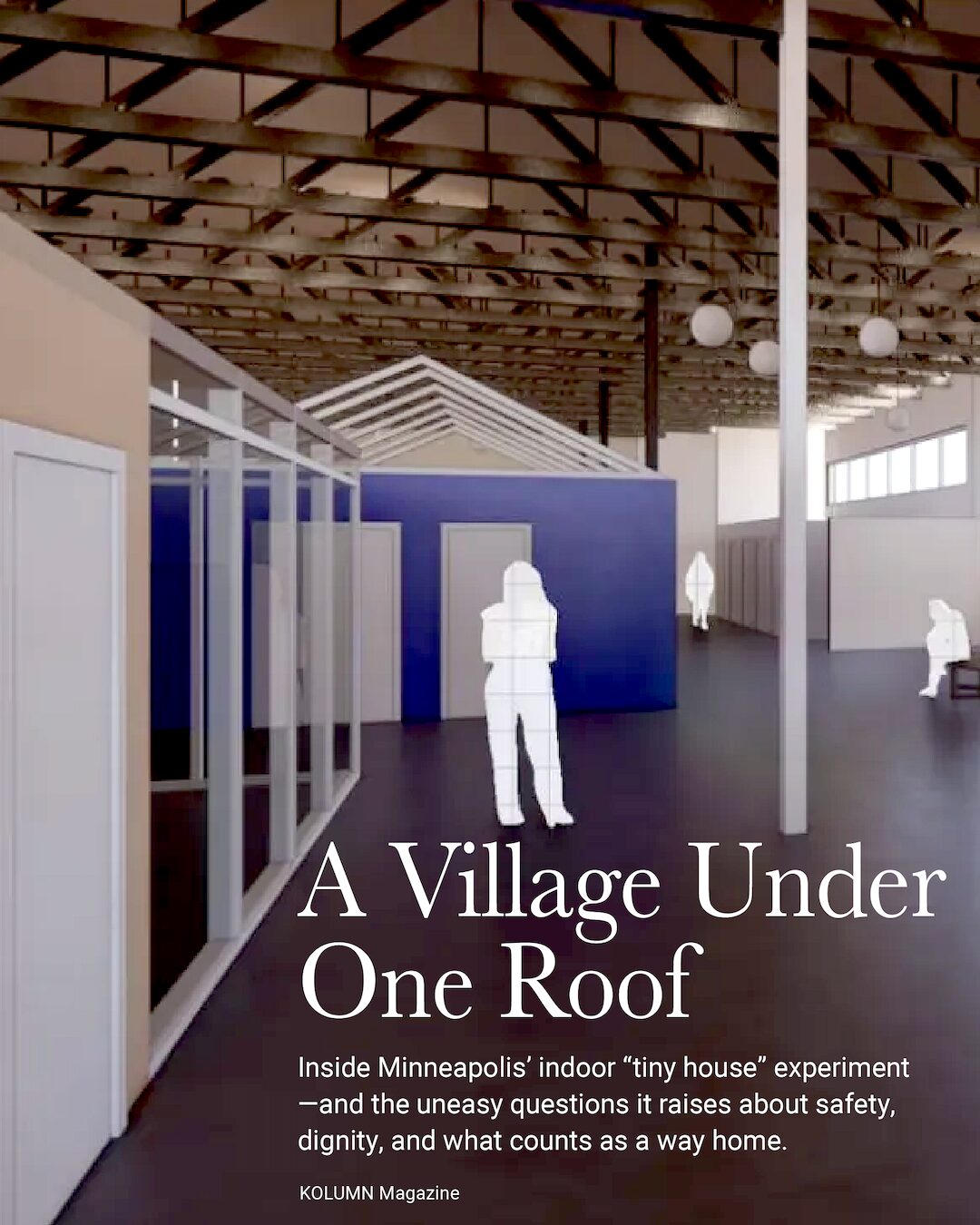

On a winter morning in Minneapolis’ North Loop, the building reads like a familiar urban story: a former warehouse repurposed in a neighborhood that has made a civic sport out of reinvention. The exterior gives nothing away. But inside, the reinvention is not a brewery or a tech office. It is a neighborhood: 100 small, brightly colored dwellings arranged in neat rows beneath an industrial ceiling—rooms with doors, locks, and keys.

The units are not apartments, exactly. They are not cots, either. Each is a private space—modest, spare, deliberately personal—designed to interrupt a pattern city leaders had struggled to break: the months and years in which people cycle between sidewalk survival, emergency rooms, jail, and the kind of congregate shelters many unsheltered residents avoid.

For many residents, the most radical feature is not architectural. It is procedural: the ability to close a door and decide what happens next.

How Minneapolis built an indoor village

Avivo Village was not the result of a long-range housing plan or an elegant bond proposal. It emerged from a compressed period of overlapping emergencies—public health, public safety, and housing—during which Minneapolis was forced to confront the reality that its shelter system was not reaching a growing segment of people living outside.

When COVID-19 arrived, it did something immediate and clarifying to the city’s existing shelter logic. Congregate settings—large rooms, shared bathrooms, dense sleeping arrangements—became both ethically fraught and epidemiologically risky. The notion of “capacity” in shelter, long measured by how many mats could fit on a floor, suddenly looked like a public-health liability. At the same time, encampments were becoming more visible, more politically volatile, and harder to manage through the familiar municipal playbook of periodic clearances.

The city’s dilemma was straightforward and unsentimental: it needed spaces where people could be indoors without being pressed into crowds; it needed to offer something that people living outside would actually accept; and it needed to do it fast enough to matter before winter—or the next wave of the pandemic—made the decision for them.

Avivo, a Minneapolis-based nonprofit with long experience in housing stability and behavioral health, arrived in this moment with an idea that felt both pragmatic and quietly radical: take the premise of a “tiny house village”—privacy, boundaries, a door that locks—and bring it indoors, into an existing warehouse, where plumbing and heat could be centralized and Minnesota weather could be held at bay.

The concept had a lineage. Avivo has said the model was inspired by Indoor Villages, an approach developed elsewhere that emphasizes individual, secure spaces within a larger structure. What Minneapolis built would be a local adaptation—scaled for 100 units, designed around 24/7 staffing and overdose response, and pitched explicitly as “low barrier”: no sobriety requirement, no mandatory treatment, with the ability to keep possessions and, in many cases, pets.

Speed mattered, and speed was enabled by the kind of money cities rarely get to spend quickly: emergency funding. Avivo’s FAQ describes the project as a two-year pilot with an estimated cost of $8 million, supported in part by CARES Act funding from the City of Minneapolis, the State of Minnesota, and Hennepin County, alongside philanthropic and service-reimbursement streams.

The building itself—1251 Washington Avenue North—belonged to Lerner Publishing Group, which agreed to lease warehouse space for the project. The selection was a study in the constraints of urban crisis response: reuse what exists, retrofit what can be retrofitted, and accept that the solution will be judged not only by outcomes, but by the speed with which it appears.

What followed was a rapid conversion that, in other contexts, might have taken years of public debate. In the Minnesota Reformer’s early reporting, the interior read almost like a stage set: a full “tiny house community” constructed inside a warehouse, built to shelter 100 people, with each unit providing a sense of private ownership inside a larger, managed environment.

Avivo’s operational details reveal another truth: low-barrier models are not “hands-off.” They are labor-intensive. Avivo describes around-the-clock staffing, wraparound services, and a design meant to support stabilization. In a November 2021 update, the organization noted that many residents spend their first days sleeping—catching up on chronic sleep deprivation—before staff begin deeper work on goals and next steps. That detail is easy to miss, but it captures the underlying premise: before housing plans and recovery plans, there is rest.

From the start, city leaders framed Avivo Village as temporary—a bridge. But the bridge metaphor contained its own warning. A bridge only works when the far shore exists: affordable units, supportive housing openings, rental options a resident can access and keep.

When shelter stops feeling like survival

For Lee Henderson, the bridge was not theoretical.

In a portrait used by Minnesota Public Radio, Henderson stands near his unit, the kind of image that looks composed until you consider what it represents: a man who has lived outside long enough to understand how quickly safety collapses, now posing in a place designed to keep collapse at a distance.

Henderson described the adjustment to being inside in language that sounded like muscle memory: at first, you still listen for everything. The body learns a kind of constant auditioning when it lives outside—footsteps, voices, the shift of someone moving too close. The idea of turning that vigilance off can feel less like relief than exposure.

And then there is the door. A door that locks from the inside is a minor luxury for most people. For someone who has slept in tents and doorways, it is not a luxury at all; it is a boundary, an assertion of personhood.

The best reporting about Avivo Village returns again and again to this point: the lock. The private space. The controlled entry. What looks like design is, for residents, a psychological intervention.

The core of Avivo’s model is not that a private room solves homelessness. It is that a private room might stop the bleeding long enough for the rest of the system to work. Avivo’s own description emphasizes “wraparound services” and “a goal of moving into permanent housing,” pairing shelter with pathways. The question has always been whether the pathways are wide enough.

A second resident, and the feeling of not guarding your life

If Henderson’s story illustrates the concept of stabilization, Jessica Eull’s story explains why stabilization can be the difference between using shelter and avoiding it altogether.

In October 2023, MPR reported on Eull’s experience at Avivo Village and her description of safety and stability—what it felt like to have a door, a secure place, the ability to settle. The story is notable not because it romanticizes the village, but because it describes the exact problem it was built to address that some people living outside do not consider traditional shelters safe, tolerable, or workable.

Eull’s presence in that reporting matters for another reason: it shows how “low barrier” becomes a practical category, not a moral one. Many shelter systems are designed around behavioral compliance. Avivo Village is designed around survival—an important distinction in a city where fentanyl overdose is a constant threat, and where the policy response increasingly resembles emergency medicine.

The numbers everyone argues about

Minneapolis’ homelessness debate often collapses into one figure: the cost.

In October 2023, MPR reported that Avivo Village costs $4.5 million per year to operate. That number covers far more than rooms: it implies 24/7 staffing, behavioral health response, controlled entry, and, as the reporting suggests, the constant reality of overdose prevention and reversal.

But the most revealing numbers sit around Avivo Village rather than inside it, because Avivo is not merely a shelter program. It is a case study in how municipal spending expands during crisis—and then must be renegotiated when crisis money ends.

The crisis-spending era

During the pandemic, cities like Minneapolis had access to unusual fiscal flexibility. Emergency funds allowed quick expansions of shelter and response infrastructure, including models intended specifically for unsheltered people. Avivo’s FAQ explicitly ties the pilot’s early funding to CARES Act support from the city, state, and county.

The point is not that the city “had money.” The point is that the city had money with the political mandate to spend it quickly. That is a rare condition in local government.

The fiscal cliff

By 2022, Hennepin County—whose homelessness response system is deeply intertwined with Minneapolis—was warning about a shelter funding “fiscal cliff,” and the Star Tribune reported the scale of the gap and the expected ramp-up in Avivo Village operating support over time.

The language of the county’s own documents is blunt. In a “solutions to homelessness” funding brief, Hennepin County laid out the projected needs: $2 million a year to continue services at Avivo Village starting in 2023, increasing to $4 million starting in 2025, alongside other shelter and homelessness initiatives.

What these documents reveal is that the public debate about Avivo Village’s cost is also a debate about the sustainability of the entire emergency shelter ecosystem created—or expanded—during crisis.

The city’s 2025 stabilization decision

In 2025, Minneapolis made its own funding move explicit. City Council records for the 2025–2026 adopted budget include $1.6 million in one-time General Fund funding in 2025 to stabilize Avivo Village’s shelter operations through capital improvements and operations support. The language is careful: stabilize. One-time. Prevent losing needed services.

That is not merely budget jargon. It is an admission that the city is trying to keep the building open in an era when emergency funding is not guaranteed—and when every program built during crisis must now justify itself against every other need.

Spending “on homelessness” is not one number

This is the hidden complexity: Avivo’s cost is visible, line-itemed, debated. But much of the public cost of unsheltered homelessness is diffuse—spread across emergency rooms, ambulance calls, policing, incarceration, and encampment clearances. Even Avivo’s own presentation materials frame the argument in those terms, noting that a comprehensive ROI analysis is difficult while also emphasizing the immediate public costs associated with encampments and high healthcare utilization.

In other words, Avivo Village is expensive in a way the rest of the system often is not: its costs appear on paper as a program, rather than emerging as a byproduct of crisis.

The criticism that doesn’t fit in a press release

Avivo Village inspires a particular kind of civic storytelling: a warehouse becomes a village; dignity is engineered; a door locks. In a country that has struggled to do anything at scale about homelessness, the model offers an image that feels like action.

But the criticism—when it comes—tends to land in two places.

First: safety inside. A 100-unit indoor community concentrates vulnerability in a single space. Conflict can follow people indoors. Some residents will feel safer; others may not. Even supportive reporting gestures at this tension by repeatedly emphasizing staffing, security, controlled entry, and ongoing operational needs.

Second: permanence. The critique from policy advocates is structural: a shelter, no matter how dignified, is not housing. The danger of any well-run transitional model is that, in a system with too few exits, the transitional becomes semi-permanent. Avivo’s own materials insist the goal is permanent housing. The question is whether the city and county can build enough housing and provide enough subsidies and supportive services to make that goal realistic at scale.

What Avivo Village reveals about Minneapolis

The most honest way to describe Avivo Village is that it is both a moral intervention and a fiscal artifact.

It is moral in the simplest way: it gives people a lockable door, a private space, and a structure designed to keep them alive. It is a response to the argument—often made in slogans and rarely acted on in budgets—that dignity should not depend on compliance, and survival should not depend on luck.

It is a fiscal artifact because it was enabled by a moment when emergency funds and political urgency aligned. The city could build something quickly. Now it must decide what happens when “pilot” turns into precedent. The 2025 one-time stabilization allocation reads like a bridge built out of budget language: keep this open, find the next funding source, avoid collapse.

For Lee Henderson, the village offered something immediate and human: enough quiet to think beyond survival.

For Minneapolis, it poses a harder question. If privacy and safety change behavior—if stability makes progress possible—then the debate is not only about Avivo Village’s operating cost. It is about whether the city is willing to pay for the conditions it now knows people need, and whether it can build the permanent housing pipeline quickly enough to ensure that this indoor village remains what it was intended to be:

A bridge, not a destination.