KOLUMN Magazine

Who Gets Protected

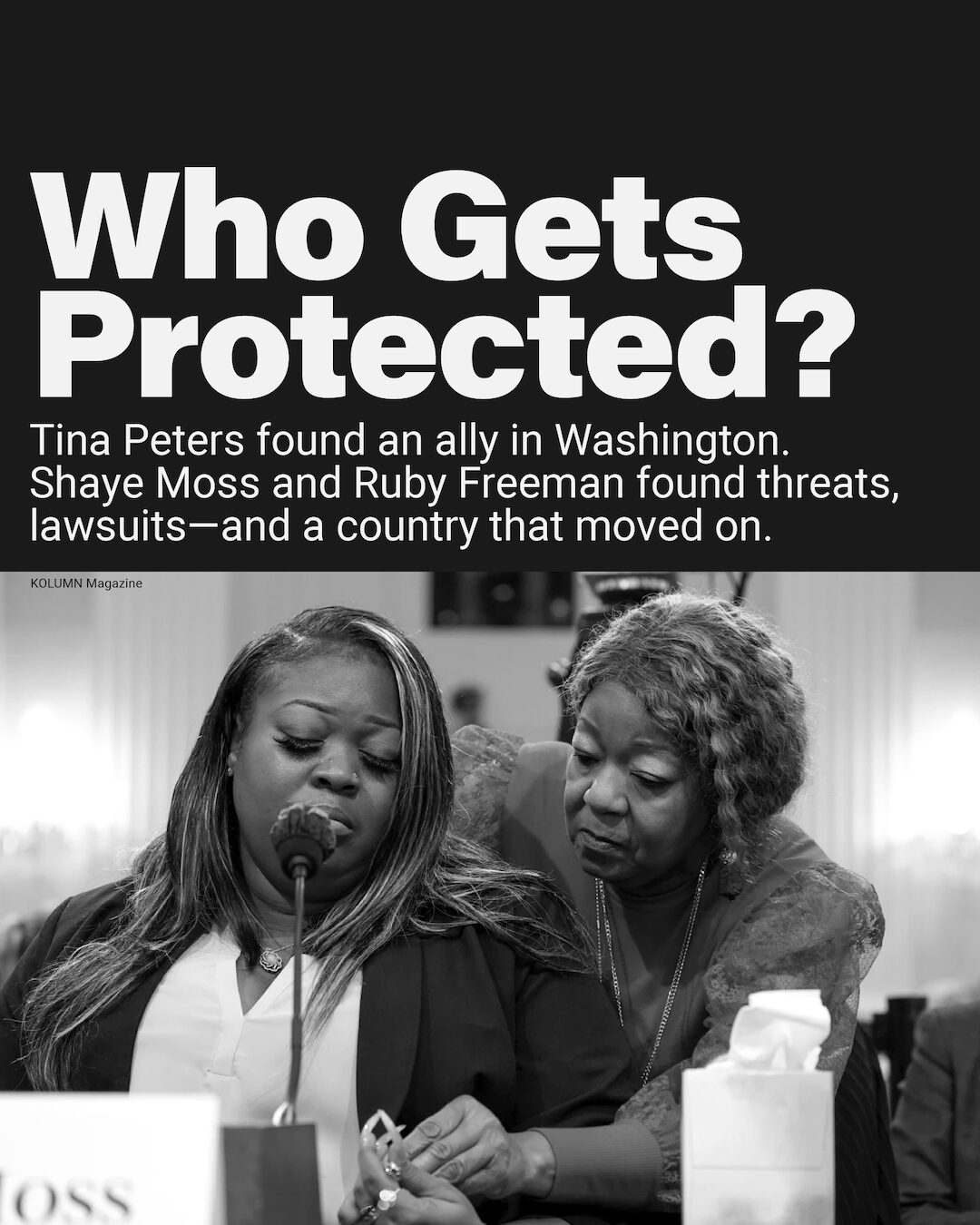

Tina Peters found an ally in Washington. Shaye Moss and Ruby Freeman found threats, lawsuits—and a country that moved on.

By KOLUMN Magazine

In Colorado, the story of “election integrity” looked like a prison roster.

Tina Peters—once the elected clerk and recorder of Mesa County, now a felon serving a nine-year state sentence for a voting-system breach—was where the state of Colorado said she belonged: behind razor wire, in a facility built for people who violate public trust. A few states away and a world apart, the President of the United States was insisting, on his social-media platform, that she was exactly the opposite: a “Patriot,” a martyr, a casualty of Democratic vengeance. He said he had granted her a “full pardon.”

In Atlanta, the women who have spent the last four years wearing the other half of that story—Shaye Moss and Ruby Freeman, mother and daughter, former Fulton County election workers swept into a national conspiracy theory—have been trying, much more quietly, to become un-famous. Their names were once repeated like incantations in the fever swamps of post-2020 grievance. They received threats that made grocery stores feel like ambushes. They described their lives being “upended” by lies told about them by the former President and his allies.

An investigative question sits between these two facts, and it is not a matter of legal doctrine, though doctrine matters. It’s a question of posture—of who is treated as a victim of democracy and who is treated as collateral damage.

Because the same Administration that cast Tina Peters as a symbol of righteous persecution has offered no comparable public effort to repair the harm done to Moss and Freeman, despite courts and investigators repeatedly rejecting the fraud claims made about them and despite a landmark defamation judgment against Rudy Giuliani, Trump’s former lawyer, for spreading those claims.

What follows is the anatomy of a split-screen America: one where a convicted election official becomes a cause célèbre for the White House, and another where two election workers—doing the unglamorous, heavily procedural work of counting ballots—become an enduring cautionary tale, referenced in reports and hearings, then largely left to fend for themselves.

The making of a martyr

The Peters case was never just about a county clerk with a grievance. It was about access—who gets close enough to the machinery of elections to touch it.

In Mesa County, prosecutors said Peters helped enable unauthorized access to election systems and allowed sensitive election data to be exposed—conduct linked to the larger post-2020 ecosystem of machine-fraud allegations and a constellation of activists, influencers, and “forensics” entrepreneurs. A Colorado judge, sentencing her, described the breach as doing “immeasurable damage” to confidence in elections; Peters’ supporters heard something else: proof that the system punishes those who question it.

By spring 2025, the posture of the Trump Administration had become unusually explicit. The Department of Justice filed a “statement of interest” signaling it was reviewing Peters’ state conviction—an atypical intervention in a state criminal matter—and cited, among other things, her health issues and deteriorating condition while incarcerated.

The move fit a broader pattern: clemency and federal muscle deployed as a kind of political backstop for allies whose legal jeopardy is inseparable from loyalty to Trump’s narrative of 2020. ProPublica, tracking the Administration’s second-term clemency practices, described a “flood” of pardons and mercy disproportionately benefiting those with access to Trump or his inner circle.

Then came December 2025, and the “pardon” itself.

Legal experts and Colorado officials quickly noted what constitutional law students learn early: presidential pardons apply to federal offenses, not state convictions. Peters was convicted in state court, under Colorado law; only Colorado’s governor has the clemency power that would actually open her cell door.

Yet the gesture was not meaningless. It was messaging—an imprimatur, a signal to the movement that Peters remained “ours.” It also provided new legal theater. Peters’ attorney publicly argued the document should apply to her state case and suggested the matter could climb toward the Supreme Court.

Even when the “pardon” couldn’t free Peters, the spectacle still did work: it reframed a conviction for election-system tampering as evidence of a persecuted truth-teller, and it placed the White House on one side of a state court’s factual findings—against Colorado’s governor, attorney general, and judiciary.

In a normal era, that would be a constitutional curiosity. In this one, it is the point.

The women in the video

The video is only a few minutes long. Grainy. Overhead. The kind of footage meant to deter shoplifting or settle insurance disputes—not to upend lives.

It shows a cavernous room inside Atlanta’s State Farm Arena on the night of November 3, 2020. Election workers move deliberately, methodically, in the hours after polls have closed. At one point, containers—standard ballot storage bins—are retrieved from beneath a table. Ballots are scanned. The work continues.

For Ruby Freeman and her daughter, Shaye Moss, the clip would become a curse.

Within days, the footage was extracted from context and repurposed into a viral accusation. On cable news and YouTube streams, on Twitter threads and fringe blogs, it was described as proof of a coordinated theft: “suitcases” of fake ballots, smuggled in the dead of night. The women at the center of the frame were named. Their faces circled in red. Their actions slowed down, zoomed in, narrated over.

The story was false. Investigators would later say so, unequivocally. But by the time the truth arrived, the lie had already done its work.

Freeman, a temporary election worker who had spent years helping to process ballots in Fulton County, first learned she was famous when strangers began appearing at her doorstep. Some were aggressive. Others claimed they wanted to “help.” Her phone filled with messages—racist, violent, explicit. One warned her to “be glad it’s 2020 and not 1920,” a line that collapsed history into threat. Another suggested she should be hanged.

Moss, who had worked in elections since she was in her early twenties, stopped answering her phone altogether. She feared going to the grocery store. She stopped posting online. She withdrew from friends. Her grandmother urged her to leave town.

What neither woman had was a megaphone.

The claims against them were amplified by the most powerful voices in American politics, including the sitting president at the time and his personal lawyer. Their names were spoken from podiums, repeated at rallies, embedded in a story that cast them not as public servants but as criminals—Black women made legible to millions as villains in a morality play about stolen democracy.

In June 2022, Moss testified before the House committee investigating January 6. Her voice was controlled, almost flat, as she described what the video had taken from her: safety, anonymity, the sense that civic participation was a shield rather than a risk.

“I don’t want anyone knowing my name,” she told lawmakers. “I don’t want to go anywhere where people know my name.”

Freeman sat behind her, silent. The camera lingered. The country watched. For a moment, there was recognition—applause, praise, a sense that the record had been corrected.

But recognition is not restoration.

Accountability arrived—then drifted away

If the attack on Moss and Freeman was public and instantaneous, accountability came slowly—and only because the women forced it to.

They sued.

Their defamation case against Rudy Giuliani became one of the clearest legal tests of the post-2020 disinformation era: could someone be held financially responsible for lies that spread faster than corrections and did more damage than any retraction could undo?

In December 2023, a jury answered yes—resoundingly. The $148 million verdict was not just compensatory; it was punitive, calibrated to signal that reputational destruction carried a cost.

Giuliani’s response was not contrition. It was resistance.

He publicly dismissed the judgment as absurd. He continued, at times, to repeat the same allegations the jury had found defamatory. He failed to comply with court orders to turn over financial records. A judge found him in contempt. Deadlines came and went. Assets remained undisclosed.

Behind the scenes, Giuliani mounted a familiar strategy: delay, diminish, and drain.

He filed for bankruptcy protection, triggering months of procedural wrangling that shifted the case from a question of harm to a question of solvency. Lawyers argued over whether his Manhattan apartment, his Palm Beach condo, his memorabilia, his future income—from podcasts, appearances, whatever remained of his brand—could be seized.

For Moss and Freeman, the process was exhausting. Winning did not feel like winning. Each filing meant another headline, another reminder that the men who lied about them still commanded attention, still found ways to center themselves in the story.

When a settlement was finally reached in early 2025, it was described as having “fully satisfied” the judgment. Giuliani kept key properties. He agreed, again, not to defame them further.

What the settlement could not do was return the years lost to fear, or the trust eroded in the idea that telling the truth is enough.

And then, as the civil case wound down, the political context shifted again.

Giuliani—now a legally adjudicated defamer of election workers—became a beneficiary of presidential clemency. The pardon did not erase the verdict, but it did something more subtle: it reframed his conduct as forgivable, even honorable, within the moral universe of the Administration.

For Moss and Freeman, this was the quietest betrayal.

They had done everything the system asked of them. They testified. They endured cross-examination. They waited. They won. And still, the federal government chose to extend grace not to the women whose lives were dismantled by a lie, but to the men who told it—and to the official who breached election systems in its name.

Accountability had arrived. Then it drifted away, not with a bang, but with a signature.

A government that hugs one story—and shrugs at another

If the Peters posture is government-as-advocate—DOJ filings, public praise, a performative pardon—then the posture toward Moss and Freeman is best described as government-as-absent.

The Administration has not centered their safety, offered a sustained public accounting of their ordeal, or treated the campaign against them as a defining scandal requiring repair. That silence becomes louder in light of what the Administration has chosen to do instead: issue sweeping pardons and clemency to allies involved in efforts to overturn the 2020 election, including Rudy Giuliani, according to multiple reports.

A pardon cannot erase a civil verdict. It cannot un-ring the bell of defamation that a jury already condemned. But politically, it functions as absolution—a signal that the lie was understandable, even honorable, as long as it served the cause.

In November 2025, Votebeat reported that Trump issued a sweeping federal pardon covering dozens of people connected to efforts to overturn the 2020 result, including Giuliani and so-called “fake electors.” NPR’s WESA, citing a former pardon attorney, described these pardons as setting an “alarming precedent.”

The contrast is stark: Peters, convicted of a voting-system breach, is treated by the White House as a wronged citizen whose liberty deserves federal attention. Moss and Freeman, cleared by investigators and validated by juries, are treated as an unfortunate subplot—proof of excesses in the information ecosystem, but not an object of executive concern.

Even the emotional framing diverges.

Peters is described in presidential language as a “patriot,” punished for “demanding Honest Elections.”

Moss and Freeman are often invoked as symbols of resilience—honored, even, with national recognition in the prior administration—yet that ceremonial recognition did not translate into a sustained political shield against a movement that continued to treat them as characters in an unresolved drama.

The country’s most powerful office is not merely choosing different legal tools; it is choosing different protagonists.

The race question no one wants to litigate—because it’s already embedded

There is an unavoidable racial asymmetry in how these stories have circulated.

Peters is a white election official who became a star within a movement that casts itself as besieged by institutions. Moss and Freeman are Black women whose work took place inside a majority-Black county in a majority-Black city, and whose vilification drew on a familiar American reservoir: the insinuation that Black urban votes are inherently suspect, that the people who count them are criminals until proven otherwise.

That pattern is not conjecture; it is part of a documented tactic. The Brennan Center has noted that fraud narratives and harassment are disproportionately aimed at election officials and workers in communities of color, putting lives at risk and corroding civic capacity.

What’s new is not the stereotype. It’s the federal government’s willingness—under Trump—to aggressively validate the storyline that empowers it.

The deeper investigative point: posture becomes policy

It is tempting to treat the Peters episode as political performance—sound and fury, legally irrelevant. But performance is part of governance now, and the Trump Administration’s posture has consequences even when courts refuse to cooperate.

When DOJ signals interest in “reviewing” a state conviction for a political ally, it invites a chilling question for every local election administrator: will the federal government punish you for safeguarding systems, and reward you for breaching them—so long as the breach is wrapped in the language of election denial?

When the Administration pardons figures who spread lies about election workers, it sends another signal: reputational terror is collateral damage the state will not only tolerate, but politically launder.

And when the victims of that terror are Black women whose work made democracy function in a contested moment, the silence reads not as neutrality but as a choice.

Moss and Freeman fought back through civil law because no other channel offered them restoration. Their verdicts became a rare moment when disinformation met consequence. But the Administration’s split-screen stance—pardon the allied arsonists, lionize the convicted insider, ignore the women whose lives were burned down—suggests the state is not just walking away from accountability. It is reassigning sympathy.

A timeline of two narratives

Dec. 4, 2020 — The video becomes a weapon (Atlanta).

A surveillance clip from State Farm Arena is publicly reframed as proof of “suitcases” of illegal ballots—an allegation fact-checkers and investigators would later rebut. (FactCheck.org)

June 21, 2022 — The women step into the light (Washington).

Shaye Moss testifies before the House January 6 committee as Ruby Freeman sits behind her—an attempt to put human faces on the costs of election disinformation. (Georgia Public Broadcasting)

June 20, 2023 — Georgia’s investigators close ranks around the facts (Atlanta).

Georgia’s State Election Board announces the “ballot suitcase” allegations were “false and unsubstantiated,” dismissing the long-running case. (Georgia Secretary of State)

Aug. 12, 2024 — A clerk is convicted (Colorado).

A jury finds Tina Peters guilty on multiple charges tied to a Mesa County election-system breach and related misconduct. (Colorado Public Radio)

Oct. 2024 — Sentence, and a movement’s new symbol (Colorado).

Peters is sentenced to nine years in state prison (the figure repeatedly cited in subsequent national reporting). (AP News)

Oct. 10–11, 2024 — Another amplifier backs down (St. Louis / Atlanta).

Gateway Pundit settles with Freeman and Moss; filings indicate the settlement would be satisfied by March 29, 2025. (Missouri Independent)

Jan. 6, 2025 — The court signals impatience (New York).

A judge finds Rudy Giuliani in civil contempt in the election-workers’ defamation case. (Reuters)

Jan. 16, 2025 — Giuliani settlement (New York / Florida).

Reuters reports Giuliani reaches a settlement with Freeman and Moss that allows him to keep key properties and agree not to defame them further. (Reuters)

Mar. 3, 2025 — DOJ enters the Peters fight (Colorado).

The Justice Department files a Statement of Interest in Peters’ federal litigation—an unusual federal posture in the ecosystem around a state conviction. (DocumentCloud)

Mar. 11, 2025 — Colorado’s rebuttal (Colorado).

Colorado officials publicly criticize the DOJ’s move as improper federal “interest” in the case. (Colorado Public Radio)

Feb. 24, 2025 — “Fully satisfied” (New York / Washington).

Reuters reports Giuliani has “fully satisfied” the $148 million judgment, following the January settlement (terms not fully public). (Reuters)

Dec. 12, 2025 — A “pardon” that can’t open the door (Washington / Colorado).

Trump announces a “full pardon” for Peters—yet major outlets and state officials emphasize a president cannot pardon state convictions; Peters remains incarcerated. (Reuters)