KOLUMN Magazine

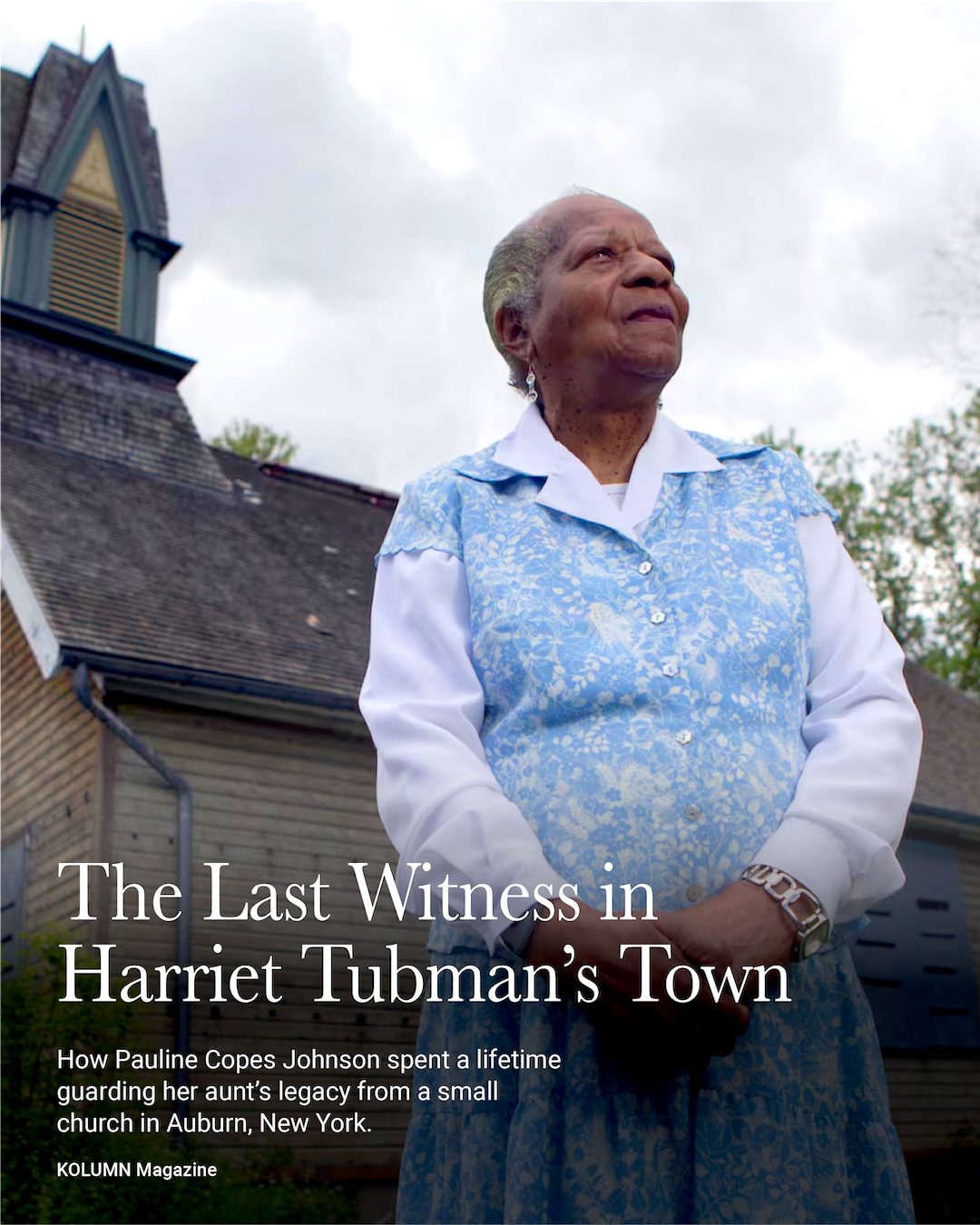

The Last Witness in Harriet Tubman’s

Town

How Pauline Copes Johnson spent a lifetime guarding her aunt’s legacy from a small church in Auburn, New York.

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a gray December morning in Auburn, New York, the announcement came not over cable news or a presidential podium, but through a Facebook post from a small brick church on Parker Street.

“The proud great-great-grandniece of Harriet and lifelong Auburn resident has passed away at the age of 98,” the Harriet Tubman Memorial A.M.E. Zion Church wrote, calling her a “treasured matriarch” and asking for prayers.

In a country that has turned Harriet Tubman into an icon fit for currency designs, museum wings, and Hollywood biopics, the death of Pauline Copes Johnson — the relative who called Tubman simply “Aunt Harriet” — might have seemed like a local story. But for nearly a century, Johnson was something rarer and more fragile than a monument: a living bridge between a woman mythologized and the family and hometown that insisted she had once been very real, very present, and very human.

“I’m advocating for her,” Johnson said a few years before her death, at 92. “I am on her side. And I’m doing the best I can to keep it going.”

Her life, tucked into the small city where Tubman spent her final years, was less about celebrity lineage than about custodianship — of stories, of land, of a church pew in which history sat every Sunday.

A childhood in Tubman’s town

By the time Auburn learned Harriet Tubman would not be put on the $20 bill — at least not yet — people there had already lived for generations with a quieter fact: Tubman had simply been a neighbor once. She bought property on the outskirts of town, worshiped at the A.M.E. Zion congregation, tended to family, and died there in 1913.

Fourteen years later, on August 23, 1927, another girl entered that same world. According to a brief autobiographical sketch she later shared with a historical foundation, Johnson was born in Auburn to Guy and Jennie Gaskin Copes and grew up as the fourth of five children in a closely knit Black family.

She walked Auburn’s public-school hallways, graduating from West High School in 1945 — a trajectory still rare for Black students in upstate New York in the middle of the 20th century, and one later recognized when she was inducted into the Auburn Alumni Hall of Distinction as part of the class of 2018.

Outside those official milestones, the details of her early life are the details of ordinary working-class Black America in the industrial North: crowded houses, shared chores, a community orbiting church and school and the rhythms of shift work. Auburn, like much of New York state, had offered itself in textbooks as “free soil.” On the ground, it was more complicated. Housing segregation and employment discrimination quietly governed who lived where and who worked which jobs.

Johnson would spend much of her adulthood challenging a different kind of erasure: not of homes or paychecks, but of memory. That project began with a revelation when she was already a young woman with a life of her own.

“Aunt Harriet”: discovering a lineage at 25

According to local accounts, Johnson did not grow up being told she was kin to Harriet Tubman. The information came later, when she was about 25.

By then she had already left high school behind, logged hours in the working world, and begun building a family of her own. Learning that the woman celebrated in school assemblies and Black-history pamphlets was in her own family tree did not immediately change her material circumstances. She still had bills to pay, shifts to cover, children to raise.

But it did change how she understood Auburn’s geography. The streets she had walked became layered with another map: one in which the path to church passed the grounds of the Tubman home, where the abolitionist had brought enslaved people to live out their freedom; in which the cemetery around the corner held the bones of someone she would now refer to, insistently, as “Aunt Harriet.”

In a televised interview decades later, Johnson explained that she saw her role less as celebrity descendant than as witness — someone who could speak about Tubman not only as a figure in a school poster, but as a family member whose footsteps had worn down the same dirt paths where she herself played as a child.

In that sense, her late discovery mirrored the country’s delayed recognition of Tubman herself: the distance between what is technically knowable and what a society chooses to remember.

Phone lines and freight lines

Johnson’s working life looked nothing like the public roles she would later inhabit as an honored descendant. For years she answered calls as an operator for New York Telephone, one of the few jobs open to Black women in mid-century Auburn that offered a measure of stability. Later, she took a post as a secretary for the Red Star Express Lines, a freight company that moved goods through the region.

The image of Tubman’s grandniece at a switchboard — routing voices across distance, connecting people through invisible lines — is almost too symbolic. But for Johnson, it was simply work, a way to help support what became an enormous household.

She and her husband, Chauncey Johnson Sr., raised 12 children. The family’s size made their house, like so many Black households in the mid-20th century, an informal community hub: cousins and neighbors coming and going, church friends dropping off casseroles, staff from local social-service agencies stopping by to check on one thing or another.

It is easy to romanticize that chaos in retrospect. The reality, by all accounts, was relentless labor: meals for 14, laundry that never ended, the emotional calculus required to keep teenagers fed, clothed, and out of trouble during the civil-rights era and beyond.

Yet even as she juggled those demands, Johnson began to take on a second, unpaid job — one that would eventually define her in the public imagination.

The keeper of Aunt Harriet’s story

By the time she reached her 90s, local reporters estimated that Pauline Copes Johnson had given “hundreds of presentations” about slavery and about Tubman’s life. Church basements, school auditoriums, community centers — if a group wanted to hear about the Underground Railroad from someone who could trace the story through her own kin, she found a way to be there.

Her talks were not the sanitized versions familiar from elementary school. In one televised segment, she recalled how enslavers tested Tubman’s strength by forcing her to pull a wagon “like a horse.” She described people kissing the ground when they crossed into Canada, unable to contain the physical relief of freedom. The language was plain, the effect devastating.

“I know they could have had people working for them on the plantations,” she said, “but they could have treated them very differently than they did.”

That sentence — with its restrained, almost stubborn understatement — carries an entire political philosophy. Johnson did not talk about slavery as an abstract institution but as a series of choices made by specific human beings. They could have done otherwise; they did not.

Her audiences were not only Black schoolchildren eager to claim a heroic ancestor, but white residents of the Finger Lakes who had grown up with a gentler narrative about their region’s role in the Underground Railroad. Tubman’s presence in Auburn had long allowed the city to cast itself as an uncomplicated beacon of freedom. Johnson’s insistence on the brutality that made Tubman necessary complicated that story.

Still, she did not reject the symbol her ancestor had become. When the biopic “Harriet” premiered in 2019, Johnson attended a local screening. She came away ambivalent: pleased that Tubman might reach a new generation, but unsatisfied with the way the film compressed and rearranged the life she knew so well.

“So much has been left out of it,” she told a reporter. The movie, she felt, “didn’t show everything that Aunt Harriet had done,” especially in Auburn. She also noted, with characteristic directness, that no one from the production had spoken to her. “If they did, they didn’t contact me,” she said.

Nonetheless, she hoped the film would nudge the country toward a more robust commemoration — including the long-promised redesign of the $20 bill. “I’m advocating for her,” she said. “I am on her side.”

In that advocacy, Johnson joined a broader circle of Tubman descendants and caretakers who have pushed for federal recognition: expanded historic sites, corrected historical markers, stronger representation in textbooks. Her voice carried particular weight because she lived not in Washington or New York City, but in the small upstate town where Tubman’s house still stands.

Church as archive

If Auburn’s streets preserved Tubman’s physical presence, the Harriet Tubman Memorial A.M.E. Zion Church preserved her spiritual one. Tubman worshiped at A.M.E. Zion congregations in Auburn, and the denomination — sometimes called the “freedom church” for its abolitionist work — remained central to Black life in the region for generations.

Johnson became the Auburn congregation’s oldest member, a role with no official job description but significant moral authority. On Sundays, she sat in the pews beneath stained-glass windows honoring her ancestor, a reminder that the distance between scripture and history, between the Red Sea and the Mason-Dixon line, was not as vast as it seemed.

From her vantage point, Tubman was not only a lone heroine but part of a much larger Black religious and civic infrastructure — the women who sold pies to finance rescue missions, the pastors who opened their basements to fugitives, the congregants who risked their own safety to harbor the enslaved.

When the church announced her death in December 2025, it described Johnson’s life as one of “courage, faith, and service,” language that could just as easily have been applied to the woman whose memory she had spent decades defending.

The church had long been one of the institutions that most fully recognized Johnson’s dual identity: as a local matriarch helping shape worship and outreach, and as a figure of quiet national significance, a living relative of one of America’s most revered freedom fighters.

Recognition, late and layered

Only in the last decades of her life did the world beyond Auburn begin to honor Johnson with the trappings usually reserved for civic leaders.

In 2010, the Auburn/Cayuga branch of the NAACP awarded her its Martin Luther King Jr. Millennium Award, citing her decades of community service and her work preserving Tubman’s legacy. In 2017, the New York State Senate named her one of its “Women of Distinction,” an honor that acknowledged her as Tubman’s great-great-grandniece and as a cultural educator in her own right.

Local institutions followed suit. The Auburn Education Foundation inducted her into its Alumni Hall of Distinction, placing her alongside military officers, artists, and athletes whose names adorn the district’s honor roll.

Municipal proclamations became almost routine. City council meetings that might otherwise have been sleepy affairs turned, on Harriet Tubman Day or during civil-rights commemorations, into small ceremonies in which Johnson stood to accept formal resolutions recognizing her ancestor’s work and her own. A photograph from March 2025 shows her standing at the front of the council chamber in a teal sweater, flanked by fellow descendants as Auburn’s mayor hands over a proclamation naming a local Harriet Tubman Day.

These recognitions did not alter her social position in the way celebrity might have. She remained, by the accounts of those who knew her, unmistakably rooted: a woman who still attended church meetings, still spoke with schoolchildren, still criticized a Hollywood movie when it did not meet her standards of historical fidelity.

Yet they did something subtler. They made visible — in plaques and resolutions and framed certificates — a truth that had long been obvious to the people of Auburn’s Black community: that bearing witness has its own civic value.

What it means to lose the last witnesses

When Johnson died at 98, she was widely described as the oldest descendant of Harriet Tubman living in Auburn, and among the oldest in the country. She was not the only relative preserving Tubman’s history — others, like Judith Bryant in Auburn or Ernestine Wyatt in Washington, D.C., have played prominent roles in public memory — but she occupied a singular place in the web of family and geography.

Her passing is part of a broader, quieter transition: the gradual loss of the last generation that grew up with people who had known Tubman personally, or who themselves were born on the same streets and in the same houses she once frequented.

For historians, that loss shifts the balance further toward documents and away from oral history. For Auburn, it raises practical questions about who will tell the story now when students come through the Harriet Tubman National Historical Park or gather in the A.M.E. Zion fellowship hall.

But the meaning of Johnson’s life does not rest solely on proximity to a famous ancestor. It lies also in the way she used that proximity — not to claim special status, but to insist that the country confront what it prefers to domesticate.

When federal debates flared over how to teach slavery and whether to name racism explicitly in school curricula, Johnson was still visiting classrooms to describe in plain language the violence her ancestor endured and resisted. When the film “Harriet” smoothed certain edges for narrative convenience, Johnson publicly called for more complexity, more Auburn, more of the unvarnished Tubman story.

Her presence functioned, in effect, as a kind of accountability. It is harder to sentimentalize the Underground Railroad when someone whose family lived its consequences is sitting in the front row, ready to raise her hand.

After Aunt Harriet’s grandniece

It is tempting, in the wake of her death, to imagine Johnson passing a literal torch — a relic from the Underground Railroad, perhaps, or a family Bible — to a younger relative as cameras flash. Real life is less cinematic.

The baton in Auburn looks more like binders of genealogical research, boxes of clippings and programs, stories learned by heart and recited so often they become muscle memory. It looks like church trustees poring over budgets to keep the doors open, city staff drafting yet another Tubman Day resolution, rangers at the national park pointing to the farmhouse where Tubman once lived.

Johnson’s own descendants — her twelve children, many grandchildren and great-grandchildren — now inhabit a country in which Harriet Tubman’s face is widely recognized but her story remains contested terrain. Some of them may choose to step into the public roles Johnson occupied; others will carry the legacy in more private ways.

In one sense, her work can never truly be finished. The fight over which stories America tells about slavery and freedom is ongoing, unfolding in school-board meetings and state legislatures, in the design of monuments and the text of museum labels. It is visible in the sluggish pace of efforts to put Tubman on U.S. currency and in debates over how to frame the Underground Railroad on federal websites.

But Johnson’s life in Auburn offers a template for one kind of response. It suggests that the custodians of history are often not the people whose names appear in history books, but the ones answering phones at local companies, raising children, sitting in church pews — and, when the time comes, standing before a classroom or a city council to say, as calmly and insistently as they can, that the past was both worse and more complicated than the brochure suggests.

In death, as in life, Pauline Copes Johnson refuses to let Harriet Tubman become a statue. She anchors her instead in the ordinary — in a small city in upstate New York, in a crowded house, in a church whose matriarch has finally gone home.